The following is an excerpt from Chapter 6 of my book The Inner Light: Self-Realization via the Western Esoteric Tradition (Axis Mundi Books, 2014).

A Brief History of Tantra

and Western Sex Magick

Eastern Tantra

The adepts of Tantra believe that…the present age of darkness has innumerable obstacles that make spiritual maturation exceedingly difficult. Therefore more drastic measures are needed: the Tantric methodology.1

—Georg Feuerstein

Before covering the essentials of so-called Western ‘sex magick’, some background on the history of Eastern Tantra is important. ‘Tantra’ is one of those words that most 21st century people on some sort of inner journey have at least heard of but usually understand only vaguely. The word is usually associated with sexuality in conjunction with certain mystical states of consciousness, but the truth is remarkably more involved than its Western New Age simplifications. Tantric doctrine is voluminous, encompassing a vast range of theory and practice pertaining to the matter of spiritual liberation, and sexuality occupies only a relatively small part of its doctrine.

The word tantra is from the Sanskrit language and has various literal interpretations, but most commonly is understood to mean ‘web’ or ‘loom’; it derives from the root tan, meaning to ‘extend’ or ‘spread’, and tra, meaning ‘to save’; the word can thus be understood as ‘spreading knowledge in order to provide salvation’.2 It is also closely related to the word tanta (‘thread’), suggesting the weaving of a tapestry that makes contact with everything in existence, leaving nothing out—a good metaphor for the all-embracing nature of its view of reality.3

Tantra has its roots in the ancient Hindu-Vedic traditions of India—the word tantra was used in the Rig Veda scriptures as far back as at least 1500 BCE—but is generally recognized as having first appeared in a coherent form in north India around 500 CE. About a hundred years after that the Buddhist version appeared (and in fact, the oldest surviving complete Tantric texts are Buddhist).4 There is a legend that the Tantric teachings were first given by the historical Buddha (around 500 BCE), but this is seen by scholars as mostly myth. It is generally accepted that Tantra as a unique form of spirituality was established by the 6th century CE in Northwestern India. Most forms of Hindu yoga (such as Hatha and Kundalini yoga) were influenced by Tantra. The Buddhist version eventually migrated (or was chased) across the Himalayas to Tibet, where, chiefly via the work of the 8th century CE Indian monk-scholar Shantarakshita, it resulted in a particular school and lineage generally referred to as the Vajrayana (‘Way of the Diamond Thunderbolt’).

The legendary figure of the great tantric mystic Padmasambhava as well as the important 8th century CE Tibetan king Trison Detsun are traditionally believed to have been involved in the transmission of the Buddhist lineage to Tibet as well. After an initial struggle with the entrenched shamanistic tradition known as Bon, the Vajrayana teachings took hold (partly by absorbing some elements of Bon) and became established. It is in Tibet, many believe, that the Tantric path became most highly elaborated and evolved; it was only after the 1959 Chinese invasion that the Vajrayana teachings were dispersed to the West following the destruction of thousands of Tibetan monasteries by the Red Army, and the subsequent exodus of many advanced Tibetan teachers (lamas) of Tantric Buddhism.

The legendary figure of the great tantric mystic Padmasambhava as well as the important 8th century CE Tibetan king Trison Detsun are traditionally believed to have been involved in the transmission of the Buddhist lineage to Tibet as well. After an initial struggle with the entrenched shamanistic tradition known as Bon, the Vajrayana teachings took hold (partly by absorbing some elements of Bon) and became established. It is in Tibet, many believe, that the Tantric path became most highly elaborated and evolved; it was only after the 1959 Chinese invasion that the Vajrayana teachings were dispersed to the West following the destruction of thousands of Tibetan monasteries by the Red Army, and the subsequent exodus of many advanced Tibetan teachers (lamas) of Tantric Buddhism.

A few generalities can be stated about Eastern Tantra. It has certain characteristics that mark it apart from more conventional forms of spirituality. Although a vast literature within the tradition exists, Tantra is less a philosophy and more a way of life based on direct experience and very structured practices. In its embrace of material existence and inner freedom deriving from practice, it bears similarities with existentialism and Zen (though probably more effective and practical than the former and more colorful than the latter). Like Zen, Tantra is not interested in dry rationality divorced from direct practice. That said Tantra is no whimsical ‘way of life’ lacking theoretical structure, as it is sometimes depicted in diluted New Age Westernized versions of it.

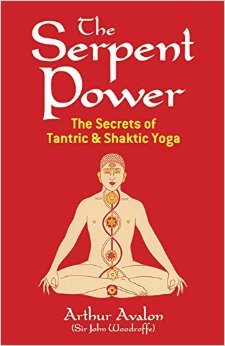

The theological basis of Tantra was described by Sir John Woodroffe (1865–1936), who wrote under the mystical pseudonym of ‘Arthur Avalon’ and was the first Western scholar of Indian Tantra, as follows:

…Pure Consciousness is Shiva, and His power (Shakti) who is She in Her formless self is one with Him. She is the great Devi, the Mother of the Universe who as the Life-Force resides in man’s body in its lowest centre at the base of the spine just as Shiva is realized in the highest brain centre, the cerebrum or Sahasrara-Padma, Completed Yoga is the Union of Her and Him in the body of the Sadhaka [practitioner]. This is…dissolution…the involution of Spirit in Mind and Matter.5

Woodroffe, who had been a judge of the High Court in Calcutta in the 1890s, courageously studied and published the first scholarly treatments of Hindu Tantra for Western audiences, during a time (early 20th century) when Tantra was still regarded as a debased and decadent version of Hindu religious tradition. This view was doubtless colored by colonial English puritanicalism; after all, the West first became aware of Tantric teachings during a century (the 19th) when the reality of the female orgasm was still being denied by many so-called medical authorities. Prior to Woodroffe’s efforts any texts concerning Tantra were typically bowdlerized by European translators so as not to offend Victorian and Edwardian morality. (A good example of this being the 1958 Columbia University Press edition of Sources of Indian Tradition, part of an ‘Introduction to Oriental Civilizations’ university series, a 900-page textbook that devotes precisely half a page to Tantra, omitting all mention of left-hand approaches. An example of a Western scholar who did treat Tantra openly and objectively was Heinrich Zimmer, especially in his Philosophies of India published by Princeton University Press in 1951 and edited by Joseph Campbell). Indian scholars themselves were often embarrassed by Tantric teachings and commonly omitted mentioning them altogether in tomes on Indian spirituality.

Woodroffe, who had been a judge of the High Court in Calcutta in the 1890s, courageously studied and published the first scholarly treatments of Hindu Tantra for Western audiences, during a time (early 20th century) when Tantra was still regarded as a debased and decadent version of Hindu religious tradition. This view was doubtless colored by colonial English puritanicalism; after all, the West first became aware of Tantric teachings during a century (the 19th) when the reality of the female orgasm was still being denied by many so-called medical authorities. Prior to Woodroffe’s efforts any texts concerning Tantra were typically bowdlerized by European translators so as not to offend Victorian and Edwardian morality. (A good example of this being the 1958 Columbia University Press edition of Sources of Indian Tradition, part of an ‘Introduction to Oriental Civilizations’ university series, a 900-page textbook that devotes precisely half a page to Tantra, omitting all mention of left-hand approaches. An example of a Western scholar who did treat Tantra openly and objectively was Heinrich Zimmer, especially in his Philosophies of India published by Princeton University Press in 1951 and edited by Joseph Campbell). Indian scholars themselves were often embarrassed by Tantric teachings and commonly omitted mentioning them altogether in tomes on Indian spirituality.

Philosophically, Tantra is, generally speaking—and the word ‘generally’ must be emphasized here as Tantra is not represented by any one authoritative doctrine—based on a radical acceptance of material reality and life-energy. In contrast to teachings that view material reality as illusory at best, or as a debasement to be overcome, or even as evil, Tantra regards corporeal existence as pure energy, divine in essence, to be harnessed and converted and even to be delighted in. In brief, Tantra includes the body in its model of spiritual enlightenment—it is a radically inclusive path, and even holds that liberation can be achieved in degenerate social conditions. This idea of working with the energies of life rather than against them (or seeking to transcend them), has become particularly relevant since the Industrial Revolution, with its emphasis on materiality, and for the general current state of our planet. There are prophecies from both ancient Hinduism and Buddhism that speak to this. The Hindu Vedic texts of old specify four distinct ages spanning our history. The last and current one is known as the Kali Yuga (‘dark age’), an age when the Tantric teachings are considered most appropriate. The idea is that in the ‘dark age’ the negative social and psychological conditions on the planet get so out of hand that the only possible way to understand them is to work with them, rather than attempt to deny, suppress, overlook, or overcome them. From the Tibetan Buddhist tradition comes Padmasambhava’s prophecy, recorded around the 9th century CE: ‘When iron birds shall fly and people shall ride horses with wheels, armies from the north will crush Tibet, and these teachings will travel west to the land of the Red man’. All this can be seen as a metaphor for appropriate timing, in that the Tantric approach is believed by its adherents to be well suited to a particular cultural milieu, namely global civilization under its current conditions.

That said, the antinomian ideology of ‘radical acceptance of material reality’ within Tantra does not mean that it is a tradition that lacks structure and discipline. To define this structure precisely is nearly impossible, as there are over five hundred Tantric lineages in India alone.6 In addition, Hindu Tantra is comparatively lacking in literature that treats its teachings comprehensively, in comparison to Tibetan Buddhist Tantra, which has a rich literature and an established lineage of accomplished practitioners. This lack of literary clarity within the field of Hindu Tantra (and the difficulty in finding Hindu Tantric adepts both accomplished in practice and knowledgeable in theory) has made it ripe for Western simplifications. As the Yoga scholar Georg Feuerstein lamented:

The paucity of research and publications on the Tantric heritage of Hinduism has in recent years made room for a whole crop of ill-informed popular books on what I have called ‘Neo-Tantrism’. Their reductionism is so extreme that a true initiate would barely recognize the Tantric heritage in these writings. The most common distortion is to present Tantra Yoga as a mere discipline of ritualized or sacred sex. In the popular mind, Tantra has become equivalent to sex. Nothing could be farther from the truth!7

The broad scope of Indian Tantra ranges from extreme asceticism (as in the Aghori practitioners, who frequent cremation grounds, usually naked, for their meditation practices), to Tantric sorcerers who deal in the business of spells and curses, to left-hand practitioners who use maithuna (ritual sexual intercourse), to relatively conventional ‘right hand path’ tantricas who practice celibacy and disciplined yogic techniques of semen retention. It also needs to be understood that Tantric theory was, in part, intended to expose the social limitations of the Indian caste system, in so doing making its practitioners vividly aware of ego-impurities related to the caste conditioning and its various prejudices.8

It is helpful here to understand what makes Tantra distinct from the great Indian tradition of Advaita Vedanta, as the two traditions, though both aiming toward the supreme goal of enlightenment, in some respects use polar opposite approaches. For Advaita all that is real is the transcendent, supreme Self. The world and all its manifest phenomena are regarded as maya (illusion). Tantra adopts a different viewpoint, instead arguing that ‘the world’ and all of its energies are simply the manifestation of divine power, or what it calls Shakti. This divine power is merely the outer expression of pure consciousness, what is known as Shiva. Thus the world need not be rejected or regarded as illusion, but rather can be understood as ‘divine form’. For Tantra existence is both consciousness and energy, whereas Advaita regards energy and all its phenomena as ultimately illusion, mere appearances, with only formless consciousness as Absolute reality.

It is helpful here to understand what makes Tantra distinct from the great Indian tradition of Advaita Vedanta, as the two traditions, though both aiming toward the supreme goal of enlightenment, in some respects use polar opposite approaches. For Advaita all that is real is the transcendent, supreme Self. The world and all its manifest phenomena are regarded as maya (illusion). Tantra adopts a different viewpoint, instead arguing that ‘the world’ and all of its energies are simply the manifestation of divine power, or what it calls Shakti. This divine power is merely the outer expression of pure consciousness, what is known as Shiva. Thus the world need not be rejected or regarded as illusion, but rather can be understood as ‘divine form’. For Tantra existence is both consciousness and energy, whereas Advaita regards energy and all its phenomena as ultimately illusion, mere appearances, with only formless consciousness as Absolute reality.

These may seem to be theoretical differences best left to scholars and religious theoreticians to quibble over, but in fact they reflect a profound difference in method and practice. Tantra embraces physical reality, including the realm of sensual experience. From a purely psychological level it is not hard to understand how the Tantric approach can be useful for those who are deeply mired in materialism and governed by a strong identification with physical life (features common of the Kali Yuga, Tantric adepts have maintained). Any approach that involves regarding physical reality as illusory requires a particular psychological maturity to avoid the dangers of repression and the denial of primitive drives (as Jung, for one, had argued).

In this regard an important concept to understand in relation to Tantra is defined by the Sanskrit term bhoga, which means, basically, ‘enjoyment of the world’. In Tantric teaching this is usually coupled with the term mukti (spiritual realization). The essential idea is that both can be embraced, although this was frequently suppressed by early writers on the Tantric traditions, who suggested that Tantric rites involving sexual intercourse were mere ‘duties’ performed with no accompanying pleasure. That notion has been ridiculed by serious scholars and Tantric practitioners, who at the very least recognize the difficulty of achieving functional sexual arousal without accompanying desire and enjoyment.9

In many respects Tantra is the Eastern parallel of the Western esoteric tradition, and this is perhaps never more evident in the view Tantra has of the different ‘levels’ of reality. Included in this are the ‘subtle planes’ or finer dimensions, which Tantric doctrine (both Hindu and Buddhist) asserts are populated by a vast range of entities, including various deities that can be supplicated to, commanded, or communed with, for any variety of reasons. For the modern psychologically sophisticated observer this may seem to be primitive animism, but the Tantric view is not simplistically dualistic. The ‘entities’ of the subtle dimensions are more properly understood as ‘energies’ having direct associations with particular regions of our mind. When Aleister Crowley famously referred to the ‘demons’ of the Goetic magic as ‘portions of the human brain’ he was, in some respects, closely mirroring the Tantric view, which while not denying the ‘outer reality’ of these entities/energies, also sees their important parallels within the human psyche.

Tantric doctrine includes specific methods for communing with divine energies in the form of particular deities. The chosen deity, known as the Ishta-devata, is invoked via intensive visualization practices, its energies awakened in the body, aided by the usage of mantras (sacred intoned sounds) and mudras (specific hand postures and movements). Both mantras and mudras on their own are believed to be potent means by which to alter consciousness or relieve the mind and body of particular stresses or diseases. In addition, Tantra employs the usage of yantras, geometrically designed images that represent particular divine energies and deities, and are simultaneously understood to be fractals, that is, miniature representations of the universe and its greater energies. (The most elaborate yantras are typically the mandalas, richly colored circular designs well known to the world mostly via the Tibetan Tantric tradition). The ultimate purpose of invoking the energies of the deities is to self-identify with them, consistent with some practices of Western theurgical magic.

For Tantra, the key to this connection between the Absolute and the human being is the body, which is held to be both a temple of the divine and a valid expression of the divine (putting it in radical contrast to most Platonic or Gnostic traditions of the West that regard the body as an inconvenient distraction at best, and a disgusting bag of fluids and waste at worst—what the alien in a Star Trek episode once referred to as ‘ugly bags of mostly water’).

Tantric tradition held a deep interest in the body and its energies, particular those of the ‘subtle’ variety, and was responsible for the idea of the chakras (Sanskrit for ‘wheel’), particular subtle energy centers that are thought to correspond to organs, glands, and psycho-spiritual domains (similar, in some respects, to the sephirot of the Kabbalistic Tree of Life). The specific map of the chakras was introduced to the West by Woodroffe in the early 20th century; it was first mentioned in a structured form in an 8th century CE text of Vajrayana Buddhism (although the concept of subtle energy channels, called nadis, was discussed in yogic texts long before). The Theosophist C.W. Leadbeater (1854–1934) adapted Woodroffe’s work and from there the New Age popularity of the chakra system grew, resulting in the vast literature on the matter of the chakras now commonly available.

Tantric tradition held a deep interest in the body and its energies, particular those of the ‘subtle’ variety, and was responsible for the idea of the chakras (Sanskrit for ‘wheel’), particular subtle energy centers that are thought to correspond to organs, glands, and psycho-spiritual domains (similar, in some respects, to the sephirot of the Kabbalistic Tree of Life). The specific map of the chakras was introduced to the West by Woodroffe in the early 20th century; it was first mentioned in a structured form in an 8th century CE text of Vajrayana Buddhism (although the concept of subtle energy channels, called nadis, was discussed in yogic texts long before). The Theosophist C.W. Leadbeater (1854–1934) adapted Woodroffe’s work and from there the New Age popularity of the chakra system grew, resulting in the vast literature on the matter of the chakras now commonly available.

The acknowledgement of material reality, and in specific the body, is a key to the Tantric world-view that the transcendent is found in the immanent; that is to say, that there is nothing that is not divine. The body becomes central to this philosophy because the body is the most obvious example of what is transitory and how that affects our experience of life, vulnerable as the body is to aging and decay. Because of the vulnerability of our bodies it is natural to view the body as mortal, limited, and by extension, flawed. Tantra teaches that this view is severely limited. In so doing Tantra offers an approach to spiritual deepening that is available for the common person, not just the renunciate. Needless to say this is also what makes the teachings so susceptible to misuse by those lacking in psycho-sexual maturity and seeking a religious or spiritual license to indulge sensory pleasure. For this reason most Tantric texts insist on a powerful sincerity of intention prior to engaging the practices, as well as a profound discipline of study and practice to support the purification of psychological motive for embarking on the path.

In sum, the general disciplines of Tantra involve the following: mastery of posture (yogic asanas) and breath-work (yogic pranayama); usage of sounds (mantra) and hand movements-postures (mudras); usage of specific geometric images (yantras); and identification with deities (Ishta-devata). Additionally, the whole practice is traditionally overseen by a qualified guru; initiation to the guru is believed to be important in that it safeguards against ego-inflation (pride and grandiosity), as well as the common stumbling blocks of the solitary practitioner, namely apathy and lack of discipline.

All of the above may be said to constitute traditional ‘right-hand’ Tantra. There is also a ‘left-hand’ path (usually known by the Sanskrit terms vamamarga or vamachara). This approach gained notoriety doubtless due to its embrace of sex (first introduced to Victorian audiences), and then became of interest particularly in the mid-to-late-20th century owing in part to the ‘sexual liberation’ of the 1960s-era and beyond. Tantra became attractive to seekers of the post-hippie era who saw it as a means to enlightenment and partying at the same time. The idea seemed enticing but of course is easily misunderstood or abused.

Left-hand Tantra, in addition to using any number of the methods of the traditional ‘right-hand’ approach, also uses practices such as ritualized sex (at times with a partner who is not one’s spouse); the consumption of meat; the consumption of alcohol (wine, generally); and practices taking place in cremation grounds for necromantic rites. These practices are highly antinomian (sexual rites opposing traditional yogic moral codes and celibacy, meat-eating opposing traditional Hindu vegetarianism, etc.), but they are all also, appearances notwithstanding, based on very definite theories of the development of consciousness.

For example, a common image of Indian Tantric art is a depiction of Shiva, naked with an erect penis, being ridden by a wild Shakti-Kali, adorned with various fearsome accessories such as daggers and a garland of skulls, the whole thing taking place in a cremation ground. Shiva here represents pure Consciousness, unattached to material existence, and Shakti represents the divine play of manifest existence, all the energies of the universe and their appearances within the vast field of form. It is in the uniting of these two principles, Shakti and Shiva—or energy and consciousness—that the divine is realized and being-consciousness-bliss (sat-chit-ananda) is embodied.

For example, a common image of Indian Tantric art is a depiction of Shiva, naked with an erect penis, being ridden by a wild Shakti-Kali, adorned with various fearsome accessories such as daggers and a garland of skulls, the whole thing taking place in a cremation ground. Shiva here represents pure Consciousness, unattached to material existence, and Shakti represents the divine play of manifest existence, all the energies of the universe and their appearances within the vast field of form. It is in the uniting of these two principles, Shakti and Shiva—or energy and consciousness—that the divine is realized and being-consciousness-bliss (sat-chit-ananda) is embodied.

Tantric texts, including those of the left-hand approach, commonly admonish those interested in such a path about the need to seek qualified guidance and avoid undisciplined indulgence, such as in this line here from Kula-Arnava-Tantra:

If men could attain perfection merely by drinking wine, all the wine-bibbing rogues would readily attain perfection.

…and with this sterner warning:

One who drinks the unprepared substance [wine], consumes unprepared meat, and commits forcible intercourse [rape], goes to the raurava hell.10

A key to ritual sex in Tantra—and this is probably the area most notoriously misrepresented or misunderstood—concerns the matter of sexual fluids. For the left-hand Tantric both semen and vaginal secretions are of central importance, believed to contain highly charged creative energy that, when harnessed properly, can become the ‘nectar of the gods’ and the key to immortality. Indian alchemy has close connections to left-hand Tantra, although the symbolism in certain matters appears to be reversed in contrast to European alchemy. For example in Western alchemy Mercury is generally associated with the feminine (and on occasion with the hermaphroditic), and sulphur with the masculine; but in Indian Tantra Mercury is connected to the semen, and sulphur to the menstrual blood.11 Be that as it may the point is to combine, in a sanctified and ritualized fashion, the male-female substances. On occasion this is understood literally, with the mixture of semen and vaginal secretions (including menstrual blood) to be ritually ingested; more often it appears to be a metaphor for the balancing of male-female qualities. (When ingested materially it is essentially the Tantric parallel of the Catholic Eucharist or Holy Communion, wherein bread and wine represent the body and blood of Christ. One rite may be using actual bodily fluids, the other only proxy symbols, but both are held to impart sacred energies to the one who partakes of them).

Left-hand Tantra often utilizes the renowned pancha-makara ritual (the ‘five Ms’), those being the following: consumption of madya (wine), mamsa (meat), matsya (fish), mudra (dry roasted grain), and maithuna (ritual sexual intercourse). Consuming wine and meat are highly antinomian acts in a Hindu society that does not eat meat and considers drinking alcohol a serious transgression, and ritualized sex (especially with a non-spouse) is completely against the norm. The usage of the parched grain has never been fully understood by scholars but was traditionally believed to work as an aphrodisiac when combined with the other substances. The ritual sex often takes the form of a group of practitioners seated in circle engaging in intercourse while a guru sits in the middle with his partner, or via coupling postures involving limbs closely intertwined (artistic stylizations of this practice can be seen in some of the famed carvings of the Khajuraho temples of central India). This sexual rite is anything but mere indulgence. It involves considerable preparatory purification rites, the whole thing designed to be a ritual re-enactment of deities (Shiva and Shakti) making conscious love. It is sensual theurgy (embodied high magic) in the most direct sense.

Western Sex Magick

For one who looks into Eastern Tantra and compares it to Western ‘sex magick’, the latter may appear to be a poor cousin in contrast to the vast literature and long established practices of the East. When the reality of Eastern influences on Western sex magick is factored in as well, it may seem, at first glance, hard to find much of value or importance in the Western traditions of esoteric sexuality. But this would be a mistake. Western traditions in this vein are as rich and potent as their Eastern parallels, even if they are, it must be granted, less coherently organized and documented. Nevertheless it is not difficult to find teachings of sacred sexuality lying at the very core of the great Western mysteries, including Renaissance high magic, alchemy, Hermeticism, the Holy Grail myths, some of the Gnostic traditions, the archetypal legends attached to Christ and Mary Magdalene, the Greek and Egyptian deities, and the Kabbalah. (Even the Knights Templar, Cathars, and Freemasons were suspected of possessing and teaching secrets of sexual energy).

While it is true that modern ideas around Western sex magick did not take coherent form until the late 19th century and well into the 20th, one does not have to go much further back than the Renaissance to find roots of the modern teachings. The Italian proto-scientist, Dominican monk, and magician Giordano Bruno (1548–1600) wrote about the means by which one’s reality can be modified and determined based in part on control of eros, the erotic force. The link between imagination, the capacity to visualize, and the magic of altering one’s inner and outer reality has always been basic to the esoteric traditions, and the key to this has been energy. It is no great secret that little can be accomplished in life without sufficient reserves of energy. When Einstein famously equated mass with energy he was scientifically quantifying what esoteric practitioners worldwide have long understood: all that appears is energy in endless manifestations and interactions. This energy can be affected via specific causes, often leading to specific results.

While it is true that modern ideas around Western sex magick did not take coherent form until the late 19th century and well into the 20th, one does not have to go much further back than the Renaissance to find roots of the modern teachings. The Italian proto-scientist, Dominican monk, and magician Giordano Bruno (1548–1600) wrote about the means by which one’s reality can be modified and determined based in part on control of eros, the erotic force. The link between imagination, the capacity to visualize, and the magic of altering one’s inner and outer reality has always been basic to the esoteric traditions, and the key to this has been energy. It is no great secret that little can be accomplished in life without sufficient reserves of energy. When Einstein famously equated mass with energy he was scientifically quantifying what esoteric practitioners worldwide have long understood: all that appears is energy in endless manifestations and interactions. This energy can be affected via specific causes, often leading to specific results.

Once it was realized the role that personal energy-level plays in success in life, it was a short leap to realize that a key to creating and sustaining this energy lay in sexual activity, and in particular in understanding the role that orgasm plays for both sexes. In sexual intercourse the key here was recognized to be the matter of male orgasm, for the simple reason that once the male ejaculated the sex act was usually over for both man and woman. As a result the practice of coitus reservatus was undertaken, wherein a man learns to engage in intercourse, to whatever degree of intensity, without ejaculating. This in turn was understood to allow for semen retention and energy preservation for the male as well as greater possibility for conscious pleasure and fuller embodiment for the female (without loss of energy).

The issue of recognizing the intrinsic sexuality of the human being, and how influential sexual energy is, was brought to light in the West (and indeed lies at the root of modern psychotherapy) via the efforts of Freud. Wilhelm Reich (1897–1957), originally a student of Freud’s, was excoriated for his ideas about the importance of the sexual orgasm in the life of the average person. Practices from Tantra and Western sex magick involve the control of sexual energy, and often the conscious inhibition of the orgasm, so may seem to be at variance with Reich’s central notion that only an orgasmic human being is psychologically healthy. But these are not mutually exclusive viewpoints. Rather, Reich’s idea may be understood as an important prerequisite for the practitioner of esoteric sexuality. That is, only a psychologically healthy (i.e., functionally orgasmic) person should attempt Tantric or sex magick practices to begin with.

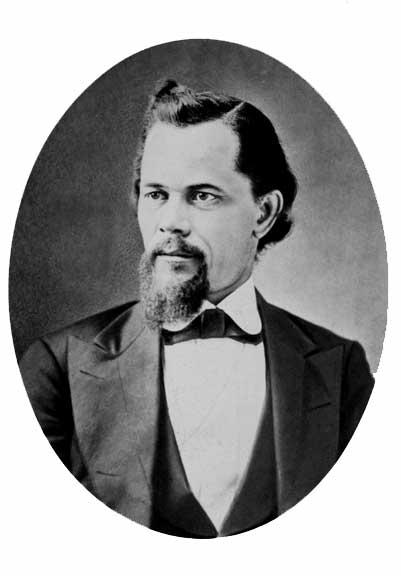

A key figure in the development of Western sex magick is generally acknowledged to be the American writer and occultist Paschal Beverly Randolph (1825–1875). Randolph, an adventurous, largely self-taught character of mixed-race descent (he counted white-European, black-African, and North American Indian blood as part of his ancestry), may have been the first North American to synthesize spirituality and an active embrace of sexuality into a coherent practice. As a young man Randolph had gained a reputation as a trance-medium in the spiritualist circles of 1850s America, but dissatisfied with this practice, embarked on a trip to Europe where he was influenced by French Mesmerists and occultists, and then followed that up a few years later with journeys to the Middle East as well as Turkey and Persia, where he came in contact with Sufism. After these influences—from which it is believed he began to put together the rudiments of his sex magick—he renounced spiritualism (passive mediumship for ‘discarnate’ spirits), and began to develop a system that involved a pro-active application of specific methods to gain control of one’s life and achieve one’s maximum potential. His emphasis on practicality was welcomed by 19th century sympathizers and students of the occult, most of whom at that time were limited to theory and abstract conjecture (Theosophy, for example, the dominant esoteric doctrine of the late 19th century, primarily taught theory). Randolph was highly influential in some circles of late 19th century esoterica.

A key figure in the development of Western sex magick is generally acknowledged to be the American writer and occultist Paschal Beverly Randolph (1825–1875). Randolph, an adventurous, largely self-taught character of mixed-race descent (he counted white-European, black-African, and North American Indian blood as part of his ancestry), may have been the first North American to synthesize spirituality and an active embrace of sexuality into a coherent practice. As a young man Randolph had gained a reputation as a trance-medium in the spiritualist circles of 1850s America, but dissatisfied with this practice, embarked on a trip to Europe where he was influenced by French Mesmerists and occultists, and then followed that up a few years later with journeys to the Middle East as well as Turkey and Persia, where he came in contact with Sufism. After these influences—from which it is believed he began to put together the rudiments of his sex magick—he renounced spiritualism (passive mediumship for ‘discarnate’ spirits), and began to develop a system that involved a pro-active application of specific methods to gain control of one’s life and achieve one’s maximum potential. His emphasis on practicality was welcomed by 19th century sympathizers and students of the occult, most of whom at that time were limited to theory and abstract conjecture (Theosophy, for example, the dominant esoteric doctrine of the late 19th century, primarily taught theory). Randolph was highly influential in some circles of late 19th century esoterica.

It is generally conceded that the important occult organization known as the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor (founded in 1870, a sort of pre-cursor to the more famous Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn founded in 1888) obtained much of its practical curriculum from Randolph’s ideas.12

It is generally conceded that the important occult organization known as the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor (founded in 1870, a sort of pre-cursor to the more famous Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn founded in 1888) obtained much of its practical curriculum from Randolph’s ideas.12

Randolph’s sex magick teachings were in some regards consistent with the left-hand path of Eastern Tantra. He did not advocate semen retention, but rather emphasized the importance of orgasm, and in particular, simultaneous orgasm for men and women. His idea was that during orgasm the mind and senses are in a heightened state, thus making it possible for the will and intention to operate much more powerfully, thereby enhancing the possibility of manifesting changes in one’s reality (everything from acquiring lovers, money, and physical health—the standard objects of ‘low’ or ‘elemental magick’).

The essential basis of sex, from the carnal to the spiritual, is of course unification, the bridging of polarities. (The erotic charge of physical sex is, in part, related to the ‘impossibility’ of two bodies actually ever truly merging, even as the passionate attempt to do so is enjoyed). Randolph was clearly deeply pre-occupied with the matter of unification; he even practiced and taught a form of trance-merging he called ‘Blending’ or ‘Atrilism’, wherein the personality is submerged into the presence of a greater personality, the latter of which operates as a source of information and energy via the conduit of the ‘lesser personality’ of the medium.13 (It should be noted, however, that Randolph counseled against casual, undisciplined usage of the practice. Max Theon [1848–1927], founder of the Brotherhood of Luxor, had more serious reservations and advised against it altogether). Randolph’s sex magic teachings did not take shape until his mid-40s, and he died at 49, so it is probable that his ideas never got beyond rudimentary form. He himself struggled greatly on the personal level (possibly clinical depression) and his death appears to have been a suicide.14 He was accused by some of getting entangled in baser forms of magic; in some ways he appears to have been a somewhat less cultured and rougher version of Crowley (see below). A perennial problem for ‘householder’ mystics and occultists has been material survival; the general path of the religious practitioner who seeks to devote their energies full time to inner development has been monastic renunciation. A mystic who chooses to embrace worldly life does not have this monastic insulation, and thus commonly resorts to cruder ways to obtain money. ‘Low magic’ or ‘sorcery’ are simply esoteric forms of ‘working it’.

Randolph proved to be highly influential. He claimed that his sources for his sex magic ideas were a combination of ‘invisible masters’ and a particular Sufi initiate he claimed to have encountered in Jerusalem. The Sufi tradition dates from approximately the same time as the coherently recorded origins of Indian Tantra (6th century CE), but there are unquestionably older hints of Tantric teachings long pre-dating Sufism.

Randolph likely had some influence on Carl Kellner (1851–1905) and Theodore Reuss (1855–1923), the ‘founding fathers’ of the Ordo Templi Orientis (O.T.O., founded around 1902), a Western occult fraternity similar in some superficial respects to Freemasonry, yet radically different in its embrace of sexual magick as a key element of its initiatic process. The O.T.O. claimed a lineage tracing back to the 18th century ‘Bavarian Illuminati’ and even the 12th century Knights Templar, although this provenance is now generally recognized as myth.

Randolph likely had some influence on Carl Kellner (1851–1905) and Theodore Reuss (1855–1923), the ‘founding fathers’ of the Ordo Templi Orientis (O.T.O., founded around 1902), a Western occult fraternity similar in some superficial respects to Freemasonry, yet radically different in its embrace of sexual magick as a key element of its initiatic process. The O.T.O. claimed a lineage tracing back to the 18th century ‘Bavarian Illuminati’ and even the 12th century Knights Templar, although this provenance is now generally recognized as myth.

Kellner, an Austrian chemist and businessman, claimed that during travels in the Near East he was initiated by a Sufi and two Hindu Tantricas; he also claimed that he had been influenced by descendents of 18th century Austrian Masonic and Rosicrucian adepts, themselves allegedly connected in some fashion to Max Theon’s Randolph-influenced Brotherhood of Luxor. The O.T.O. is of significance here primarily because of the role Aleister Crowley played in it, and in his subsequent marked influence on 20th century ideas of sex magick.15 Crowley’s life story has been amply documented in numerous biographies, but needless to say his notoriety as a so-called ‘sex magician’ (as well as prolific author, accomplished poet, mountain climber, genuine mystic, and hedonistic occultist) led eventually to both his fame and infamy. His connection to modern Western notions of Tantra is important but often unrecognized. Although knowledgeable in most matters of the Western esoteric tradition as well as Eastern traditions such as Raja Yoga, Taoism, and the I Ching, Crowley, as with many during his time, was limited in his actual knowledge of Indian Tantra. As Hugh Urban observed:

Ironically, despite his general ignorance about the subject, and arguably without ever intending to do so, Crowley would become a key figure in the transformation and often gross misinterpretation of Tantra in the West, where it would become increasingly detached from its cultural context and increasingly identified with sex.16

Kellner and Reuss had taken certain of Randolph’s basic (and relatively tame) ideas of sex magick and added entirely new elements to them, in formulating the inner doctrines of the O.T.O. These included the usage of semen to anoint a particular ‘sacred’ material symbol (such as a talisman, for example), immediately following an act of ritualized intercourse, as well as acts involving masturbation and anal sex. It is generally conceded that these activities would have been rejected by the more conservative Randolph. In 1912 Reuss paid a visit to Crowley and accused him of publishing certain secrets of sex magick ‘belonging’ to the O.T.O. in Crowley’s The Book of Lies. Crowley convinced Reuss that he had hit upon these ideas independently (which was true). The end result was that Crowley was empowered by Reuss as an O.T.O. adept. Reuss became ill in 1921 and resigned as leader of the O.T.O. in 1922; shortly after Crowley assumed leadership. He then modified some of its core rituals, expanding the nine rituals to eleven while he was at it. These added rituals included sexual acts that typically offend conventional moral standards, especially those of Crowley’s day. These included the 8th degree which involved masturbating on the sigil of a demon, as well as the 9th that included the left-hand Tantric practice of ingesting sexual fluids (sucked out of the female following intercourse). The final degree, the 11th, involved anal intercourse. All of these acts can be understood as part of the psychology of transgression, that is, they derive their erotic power from the tension of ignoring the restriction of a taboo. This erotic power can, in turn, be used as a means by which to accomplish aims, such as changing particular circumstances in one’s life. It can also function as a potent metaphor for the entire process of breaking free of the limitations of the egocentric self, in order to achieve a glimpse of unobstructed consciousness.17

An interesting and significance aspect of the development of Western sex magick involved some of the 19th century misunderstandings of Indian Tantra, part of which involved (and still involves) confusing the famed Kama Sutra texts with Tantra. The Kama Sutra, essentially a ‘how-to’ manual on the erotic arts, is older than Tantra (in its doctrinally coherent form), originating around the 3rd century BCE, but has little to do with actual Tantric teachings.

The idea of semen combined with menstrual blood as an elixir to be ritually consumed was not unique to certain schools of left-hand Indian Tantra (let alone to the founders of the O.T.O. or Crowley). It was also found within early Christian era Gnostic sects known variously as the Borborites and Phibionites (descended from the Christian ‘heretics’ known as the Nicolaitians, a sect that had been soundly condemned by the early Church fathers as gross hedonists). Anyone even casually acquainted with Gnosticism may find this surprising as most Gnostic sects were anti-material, regarding the physical universe and especially the body as ‘prisons’ in which the spark of divinity has been trapped. An early central Gnostic text cautioned that ‘it is not to experience passion that you have been born, but to break your fetters’.18 Another common Gnostic idea was that the body of Jesus was only an appearance, lacking corporeality, the implication being that the divine cannot fully enter the physical. Such views could only be seen as diametrically opposed to left-hand Tantra, to say nothing of Western ideas of sex magick originating from Randolph, Kellner, and Crowley.

The idea of semen combined with menstrual blood as an elixir to be ritually consumed was not unique to certain schools of left-hand Indian Tantra (let alone to the founders of the O.T.O. or Crowley). It was also found within early Christian era Gnostic sects known variously as the Borborites and Phibionites (descended from the Christian ‘heretics’ known as the Nicolaitians, a sect that had been soundly condemned by the early Church fathers as gross hedonists). Anyone even casually acquainted with Gnosticism may find this surprising as most Gnostic sects were anti-material, regarding the physical universe and especially the body as ‘prisons’ in which the spark of divinity has been trapped. An early central Gnostic text cautioned that ‘it is not to experience passion that you have been born, but to break your fetters’.18 Another common Gnostic idea was that the body of Jesus was only an appearance, lacking corporeality, the implication being that the divine cannot fully enter the physical. Such views could only be seen as diametrically opposed to left-hand Tantra, to say nothing of Western ideas of sex magick originating from Randolph, Kellner, and Crowley.

According to the early Church fathers there was a tradition of libertine groups loosely affiliated with early Christianity, such as the Carpocrations, who allegedly believed that all forms of vice (including morally debased acts) should be experienced in order to avoid rebirth into another body after death. Carpocrations did not appear to be Gnostic in the classic sense, but the Borborites were, holding many common Gnostic myths within their teachings (such as the creation of the World by the false god Ialdobaoth, the duality within human nature, and the incarnation of the perfected spirit Christ within the human mortal Jesus of Nazareth). The Borborites, mentioned above, added unique elements, based on the idea that a task of humanity is to ‘collect’ scattered remnants of wisdom that have been dispersed throughout the material universe (stemming from the original calamity of the creation of the universe, which Gnosticism in general claims was an elaborate error). Part of the process of ‘collecting’ involved, according to the Borborites, consuming sexual fluids as a Eucharist. The following was recorded by the Gnostic critic St. Epiphanius:

They hold their women in common…they serve lavish meats and wines…after a drinking party…they turn to their frenzied passion…and when the wretches have intercourse with one another…in the passion of their illicit sexual activity, then they lift up their blasphemy to heaven. The woman and the man take the male emission in their own hands and stand gazing toward heaven…and they say, ‘we offer unto you this gift [semen], the body of Christ and the anointed’, and then they eat it, partaking of their own filthiness…and likewise of the woman’s emission: when it happens that she has her period, her menstrual blood is gathered and they mutually take it their hands and eat it. And they say, ‘This is the blood of Christ…’19

Because the only sources of this information are polemical writings by Church fathers seeking to discredit Gnosticism—including allegations by St. Epiphanius that the Borborites went so far as to induce abortions and ritually eat embryos—the whole matter is obviously questionable, and yet the striking similarity of the sexual practices involving male and female emissions (along with the mention of wine and meat) with those of some of the left-hand sects of Indian Tantra strongly suggests that they are authentic. (It is also interesting to note, if only in passing, that the Gnostic sects employing such left-hand practices are older, by a few centuries, than most of the recorded doctrine of Hindu or Buddhist Tantra).

A key to understanding the ideology behind such practices can be found in this Gnostic Phibionite passage:

It is I who am Christ (the anointed), inasmuch as I have descended from above through the names of the 365 rulers (archons).20

These words were spoken by one who had completed a series of ritualized sexual intercourse. All of it relates to the idea of the ‘descending current’ of spirituality—materializing the spiritual. In most traditional ‘right hand’ spiritual philosophies, the idea is to encourage the ‘ascending current’—to spiritualize matter—to rise, to ascend, to transcend, to resurrect. The so-called left-hand approach is principally about the reverse, i.e., ‘earthing’ the spiritual. Some have likened the right-hand approach of spiritualizing the material to the path of the serpent (kundalini ‘rising’ up the chakras), and to the alchemical idea of solve (break down); and the left-hand approach of materializing the spiritual as the path of the dove (the descent of spirit into matter), and the alchemical idea of coagula (rebirth).21 Shorn of all moral and ethical concerns, the formula is straightforward: the essential idea of both Tantra (whether left or right hand) and sex magick is to work with our lot in material reality in such as way as to achieve our higher purpose for being here. That higher purpose is conceived of as a deep embrace of our conditions (as opposed to rejecting or renouncing them). The goal is nothing less than a radical personal metamorphosis: a structured process of breaking down the egocentric barriers of the personality so as to allow for the emergence of an embodied and profoundly fulfilled consciousness. When sexual fluids are regarded as sacred ambrosia worthy of ritualized practices, it can be taken as a deep metaphor for recognizing the divine as both a creative force and a material reality.

Notes:

1. Georg Feuerstein, Tantra: The Path of Ecstasy (Boston: Shambhala Publications, 1998), p. 8.

2. Mary Scott, Kundalini in the Physical World (London: Penguin Arkana, 1983), p. 16.

3. Feuerstein, Tantra: The Path of Ecstasy, p. 1.

4. Philip Rawson, The Art of Tantra (London: Thames and Hudson, 1992), p. 17.

5. Arthur Avalon (Sir John Woodroffe), The Serpent Power: The Secrets of Tantric and Shaktic Yoga (New York: Dover Publications, 1974, first published in 1919), p. 27.

6. Scott, Kundalini in the Physical World, p. 16.

7. Feuerstein, Tantra: The Path of Ecstasy, p. xiii.

8. Rawson, The Art of Tantra, p. 24.

9. Ibid., p. 24.

10. Feuerstein, Tantra: The Path of Ecstasy, p. 231.

11. Ibid., p. 233; compare with Titus Burckhardt, Alchemy: Science of the Cosmos, Science of the Soul, p. 140.

12. Joscelyn Godwin, Christian Chanel, John P. Deveney, The Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor: Initiatic and Historical Documents of an Order of Practical Occultism (York Beach: Samuel Weiser Inc., 1995), pp. 40–41.

13. Ibid., p. 41. This is arguably the best description for the process underwent by such well-known late 20th century ‘mediums’ as Helen Schucman (who wrote A Course in Miracles via dictating information from a ‘Voice’ that claimed to be Jesus), and Jane Roberts, who ‘channeled’ the presence and thoughts of the incorporeal ‘higher dimensional’ entity called Seth.

14. Ibid., p. 45.

15. I have written about Crowley in a previous work of mine, The Three Dangerous Magi: Osho, Gurdjieff, Crowley (O-Books, 2010). The most comprehensive biography of Crowley is Richard Kaczynski’s Perdurabo (North Atlantic Books, 2010).

16. Hugh Urban, www.esoteric.msu.edu/VolumeV/Unleashing_the_Beast.htm, accessed November 22, 2012.

17. Ibid.

18. Bentley Layton, The Gnostic Scriptures (New York: Doubleday, 1995), p. 199.

19. Ibid., pp. 206–207.

20. Ibid., p. 210.

21. For this, and a good discussion on the philosophy of Crowley’s sex magick in contrast to Tantra, see Gordan Djurdjevic, Aries: The Journal for the Study of Western Esotericism,10.1 (2010), 85–106, available online.

Copyright P.T. Mistlberger and Axis Mundi Books, 2014, all rights reserved.