The following is a continuation of the previous section (Seven Sages, Part I), excerpted from my book Rude Awakening: Perils, Pitfalls, and Hard Truths of the Spiritual Path).

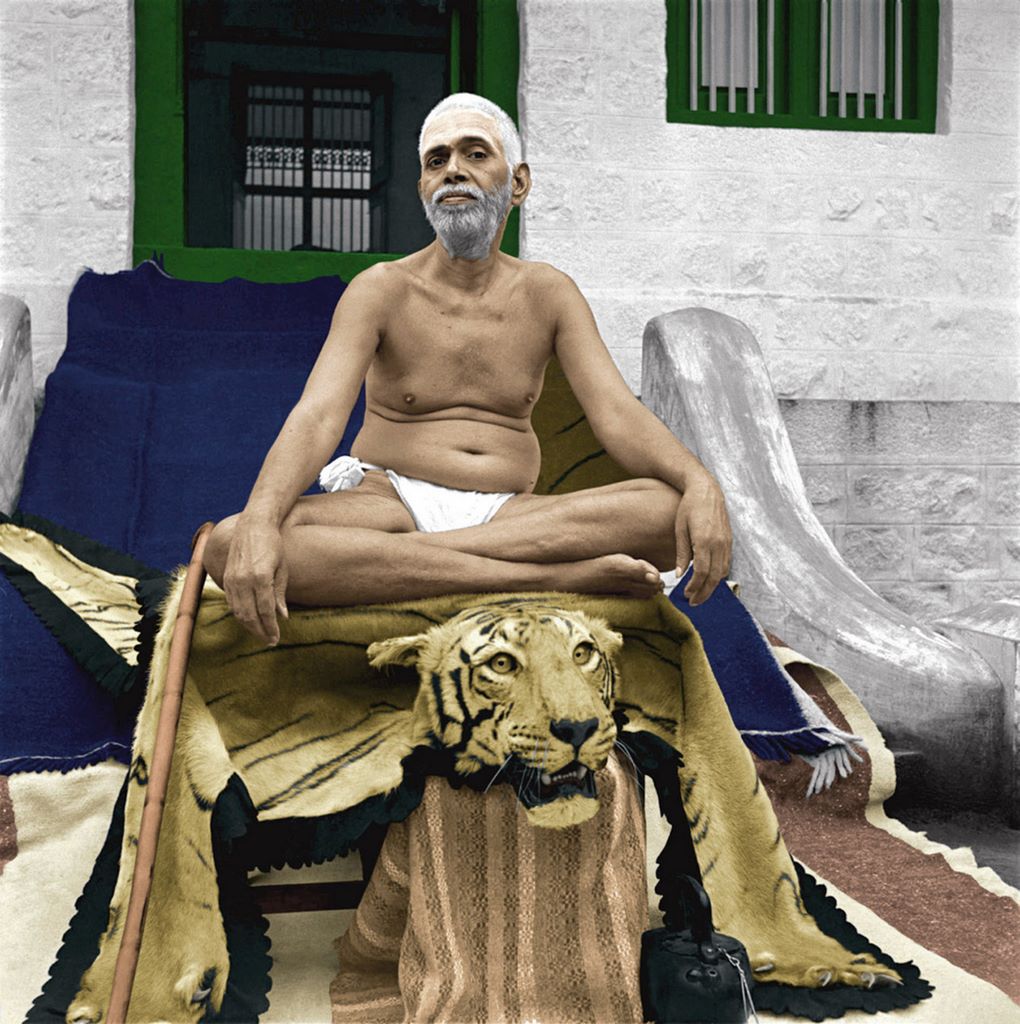

Ramana Maharshi: Solid as a Mountain

Ramana

Maharshi was one of the rarest lights of wisdom of the 20th century,

one of the few high profile gurus of recent times who was not just

scandal-free, but who escaped any noticeable criticism as well (and most

notably, from his peers). His rarity lay partly in his purity and in his utter

simplicity. Following a profound and radical awakening at age 16, he

subsequently spent fifty-four years around one particular small mountain. He

was a living, breathing demonstration of one who had clearly gone beyond all

personal agenda or egocentric desire. Although born into the Hindu tradition,

and essentially teaching Advaita Vedanta (generally recognized as the cream of

the Hindu wisdom teachings), he was in many ways the quintessential Buddha,

manifesting to a high degree of perfection such Buddhist ideals as penetrating

wisdom, utter non-attachment, desirelessness, and compassionate action (via his

tireless teaching).

Ramana

Maharshi was one of the rarest lights of wisdom of the 20th century,

one of the few high profile gurus of recent times who was not just

scandal-free, but who escaped any noticeable criticism as well (and most

notably, from his peers). His rarity lay partly in his purity and in his utter

simplicity. Following a profound and radical awakening at age 16, he

subsequently spent fifty-four years around one particular small mountain. He

was a living, breathing demonstration of one who had clearly gone beyond all

personal agenda or egocentric desire. Although born into the Hindu tradition,

and essentially teaching Advaita Vedanta (generally recognized as the cream of

the Hindu wisdom teachings), he was in many ways the quintessential Buddha,

manifesting to a high degree of perfection such Buddhist ideals as penetrating

wisdom, utter non-attachment, desirelessness, and compassionate action (via his

tireless teaching).

He was

born Venkataraman Ayyar on December 30, 1879, in a small village in Tamil Nadu,

the southernmost state of India, the second of what would become a family of

four children.8 At this point most biographers of his life tend to

remark that Venkataraman was apparently a rather ordinary boy growing up,

athletically inclined, and somewhat lazy in his studies, but that he did have

one notable feature and that was an exceptional memory. (He would use this

memory to get by on his studies without putting in too much effort). However if

one reads the stories of his youth closely enough it becomes clear that he was

not quite ‘ordinary’. He did have some strong qualities, in addition to his

outstanding memory. In particular he was given to a type of remarkable

steadfastness (or stubbornness) that showed in several ways. For one, he was an

unusually deep sleeper. In his later years he would tell comical tales of how his

childhood mates, fascinated with how difficult it was to wake him, used to

carry his body around, slap him this way and that, and then put his body back

in bed, all the while the boy never waking and not knowing anything of what had

happened. This apparent ability to be inwardly immoveable like a mountain—a

fascinating foreshadowing of his later deep affinity for one famed mountain and

his decision to spend his whole life living by it—would serve him well in two

keys ways. The first was when he underwent his great awakening (by dint of

sheer focus and determination), and the second when he refused to allow himself

to be controlled by his uncle and elder brother after his awakening (see

below).

In

addition, Ramana’s biographer David Godman reported that the young Venkataraman

was known to be very lucky; for example, whatever sports team he would play

for, that team would invariably win. As a result he was called Tangakai (‘golden hand’). What we

typically dismiss as ‘good luck’ can also be associated with an ability to be

present with what one is doing. The old expression in sports is ‘a good player

creates good luck’. A ‘good player’ is, at heart, one who can truly focus, who

can truly be present with what it is he is doing (the best athletes tend to be

the most committed, just as the ‘best’ in most activities in life tend to be).

Venkataraman’s

father passed away when he was 12 years old, and which point the boy and his

siblings went to live with his uncle. As he entered his adolescence there were

no signs of what was going to happen to him in a few short years. His first

spiritual glimmerings began to be awakened in 1895, shortly before he turned

16. These consisted of his hearing someone speak the name of the south Indian

holy mountain ‘Arunachala’; Venkataraman was struck by the sound and quality of

the name. Shortly after he read a book about some south Indian saints and a

spark was ignited. His is not the story of an adult who stumbled onto the path

of illumination, or who was ‘forced’ to it by difficult circumstances—much like

Hakuin, he had the innate disposition of the truth-seeker par excellence, and so responded naturally and enthusiastically,

even at that tender age, to the writings and stories of wise sages.

It was

in mid-1896, at age 16, when his famous awakening occurred. It was precipitated

by an intense fear of death that suddenly overtook and overwhelmed him.

Arguably it was similar to a sudden psychotic break, because the fear arose out

of nowhere and immobilized him. As he described it, the shock drove his mind

inward with what must have been an extraordinary degree of force. He then lay

down on the ground and, feeling his body frozen, began to examine his mental

processes carefully with minute attention. He truly believed he was dying, and

so this permitted him a measure of detachment from his body. In a remarkable

display of natural spiritual maturity, he conquered the fear and his panic

subsided. He then intentionally dramatized the process of death, holding his

breath and enacting a rigor mortis.

What soon emerged was the sudden realization that his true nature was not the

body, or the earthly identity-personality known as Venkataraman. His real

nature was pure Consciousness, or what he would later call ‘the Self’. He

further observed that he now became fully absorbed in the Self, and experienced

a steady and passionate fascination with this timeless Presence that he tacitly

realized was his own actual nature. This soon led to the realization that ‘he’

was not ‘absorbed into’ the Self. He was

the Self.

And basically, that was it. What is so remarkable about this story is that awakenings of this nature are not altogether uncommon (even if not of this depth), especially among devoted and committed mystics or meditators. However in almost all cases such an awakening is temporary, and even more commonly, is but a glimpse. Typically a truth-seeker, upon having such a glimpse, or even an awakening that lasts for several days, soon returns to the usual identification with the personality and body. But in Venkataraman’s case the break between ‘sleep’ and ‘awakening’ was both profound and final. There would be no going back after this event, no retreating into a conventional life. As it turned out his powerful premonition of death that preceded the awakening was, essentially, correct—it was just that identification with the ego-mind died, not his physical body. (That is not to say that Ramana’s inner process was over—he subsequently spent many years adapting his body-mind to his awakening to the Self—but the essential insight into his true nature was, in his case, both total and irreversible).

His awakening event—and ‘event’ is the correct word, not ‘experience’—apparently unfolded in the course of a mere thirty minutes. Arthur Osborne, one of Ramana’s chief chroniclers, reported that Ramana had completed in half an hour what most seekers ‘take an entire lifetime, or several lifetimes, to achieve’. He further points out that there was nothing ‘effortless’ about this attainment. The young boy had, in fact, employed a combination of enormous intensity, determination, and passion in one half-hour burst to break through the barriers of the mind that stand in the way of full realization of the Self.

Following

his awakening Venkataraman opted to tell no one what had happened, and

continued to attend school. However he found himself disconnected from most of

what was around him. He went through the motions with his school work, began to

lose interest in relations with other people, and even lost interest in the

taste of food (he reported that he continued to eat as before, but didn’t care

whether what he was eating tasted good or not). He also reported that his

behaviour with others became indifferent, even submissive at times, because he

had lost all egocentric tendencies to retaliate, to compete, to prove himself,

and so on.

All

that might sound perilously close to some sort of mental illness—in particular,

‘depersonalization syndrome’ as psychoanalysis terms it—but in fact the boy was

not emotionally disconnected and had not lost the ability to feel alive or

passionate. It was rather that his passion had been re-directed toward a much

loftier view. Even as he lost all interest in what his schoolmates were up to—the

usual thing 16 year olds everywhere are up to—Venkataraman was in fact paying

nightly visits to a particular temple where, full of passion and deep emotion,

he would stand for hours in front of certain icons, such as those of Shiva or

Nataraj, sometimes with tears streaming down his face.

About two months after his great awakening, in late August of 1896, matters came to a head. Venkataraman’s uncle and older brother did not approve of his constant absorption in meditation and his neglect of his school studies, and made no bones about it. One day, while performing some routine school homework, the boy was suddenly seized with an overwhelming realization that he could no longer go through the motions of being a normal schoolboy. He put aside his homework and sank into meditation. His older brother rebuked him, suggesting that Venkataraman was unworthy of the comfortable home life that he was being provided with. Realizing that in some ways his brother was correct, Venkataraman seized the moment and determined to leave home for good. He resolved to travel south, to the sacred mountain of Arunachala.

Many adolescent boys (or girls) dream about running away from home, but few do it, and even fewer make it permanent if they do. And those who do are usually doing so on the basis of some sort of resentment toward their family or their caretakers. Venkataraman’s case was all the more unusual because he left not out of any resentment, but simply because he had become completely disconnected with conventional life. Not because he ‘rejected’ such a life, but rather because a profound passion for spiritual truth had been awakened in him to such an extent that nothing else mattered anymore. He simply wanted to be left alone to enjoy, and reside in, his absorption in the Self, as the Self.

He was

given a small amount of money by his aunt, which turned out to be enough (along

with later selling his Brahman-caste earrings) to travel south by train, and

then foot, until he reached Mt. Arunachala. He arrived on September 1st,

1896, and would not leave the mountain’s side until he passed away on April 14,

1950. In many ways his ‘story’ ends here, although he would spend more than

half a century teaching, and radiating the Presence of his true nature.

The Sage of Arunachala

After initially arriving at the sacred mountain Venkataraman found a nearby temple, which was wide open and empty when he arrived. He entered and sat in blissful meditation. The next day he strolled through the town and proceeded to shave his head and throw away his remaining pocket change. In short, he was committing to the life of the renunciate. It’s very easy to misuse such a path, for example by using it as a disguise to hide from the world or from worldly responsibilities, but in Venkataraman’s case it was clear that his renunciation was the natural outer expression of the depth of his inner awakening. All true awakening involves a radical break or discontinuity with something—not necessarily with one’s hair or one’s clothes or money—but it always involves a profound demonstration that is possible only because of the certainty—the ‘true’ faith, essentially—aroused by the awakening.

Venkataraman

spent a number of weeks in seclusion, meditating in the temple. Some local

boys, intrigued by a lad around their age sitting motionless day after day,

began to taunt him and throw stones at him. Accordingly Venkataraman decided to

retreat further into the temple, into one of its subterranean vaults. This act

alone was highly courageous and yet another demonstration of the boy’s depth of

trust in his awakening, because the vault was old, neglected, dark, and had

nothing in it but vermin and bugs. The boys who had been taunting him were too

afraid to enter the vault so contented themselves with throwing objects at the

entrance to the vault. They were eventually chased off by a passerby who,

directed by a local mystic who had been fruitlessly trying to protect

Venkataraman from his tormentors, descended into the vault. The passerby was

astonished by what he saw: a motionless adolescent boy absorbed utterly in

profound trance, with his legs covered in wounds from the bites of vermin and

bugs. His inner absorption was so pronounced that he apparently was unaware (or

didn’t care) that he was being bitten. He went into such deep trances that he

neglected to care for even the most basic of needs for his body, such as food

and water. The benevolent passerby, concerned, conferred with a local swami,

and they and some others had the boy carried out of the vault. Venkataraman

remained largely unresponsive for another couple of months (he was practically

force-fed in order to keep him alive). It’s a testament to the spiritual

maturity of Indian culture (at least at that time and place) that the boy was,

in fact, cared for. In most other cultures such a boy would likely have met

with a worse fate, or at least, would have been treated in a manner that would

have been unsupportive, with the intent of invalidating his experience.

According to most teachings on the matter of enlightenment, Venkataraman’s state at that time was characteristic of an earlier stage of realization, what is sometimes called Nirvikalpa Samadhi. In this state the mind is absorbed inwardly, in a form of trance, even to the point of the body being practically immobilized. A younger contemporary of Ramana, the Indian sage Meher Baba (1894-1969), devoted part of his life work to helping certain mystics who were absorbed in such a state. Meher Baba referred to them by the Sufi term ‘mast’ (literally, ‘intoxicated with God’) and mentioned how easily it was for them to be mistaken for insane people.

At this

time Venkataraman began to be known as the ‘Brahmana Swami’. He was initially

cared for by a mystic named Mouni Swami (mouni

being the Sanskrit word for ‘silence’), who in addition to protecting him also

arranged for the minimum necessary daily nourishment for the young sage’s body.

The boy soon found a nearby tree that he spent weeks sitting under, deep in samadhi. It was around this time that

some passing pilgrims began to gaze upon the luminous young sage and some even

prostrated before him. A wandering seeker named Uddandi, who had spent years

studying and meditating but felt frustrated by his lack of progress, noticed

the youthful Brahmana Swami and became his first disciple, even though there

was no verbal teaching. The boy merely continued to sit in silence, yet his

demeanour and the quality of presence around him suggested to Uddandi that he

was self-realized, and that to merely sit in his company would be direct

spiritual instruction itself. The ‘silent transmission’ approach would always be

Ramana’s main teaching method.

Soon after, more pilgrims found the young sage, including a seeker named Palaniswami, who immediately recognized Brahmana Swami as his master and spent the next two decades serving him as his main attendant. The sage was soon moved by caring attendants to a nearby orchard grove, and it was here that he began to engage his intellect again by reading various scriptures in Tamil or Sanskrit so as to answer questions brought to him by Palaniswami. In this way the young Brahmana Swami was prepared for more intellectual seekers who would attach themselves to him as disciples in future years.

All this time the young sage’s family, especially his mother, had been distressed by his disappearance and had sent out small search parties to try to find him. Through various connections they eventually tracked him down in late 1898, about two years after he had left home. One of his uncles implored the swami to return to his family, assuring him that they would not interfere with his chosen ascetic path, and that there was even a nearby temple where he could stay and be cared for. Brahmana Swami was entirely unresponsive. He simply refused to allow for any attachments to be reinforced by providing false hope. Several months later his mother and older brother visited the young sage, with his mother trying, day after day, sometimes tearfully and sometimes angrily, to get him to return home. (The fact that the young swami’s body was largely uncared for—like a typical Indian sadhu he had grown thin, rarely washed and his hair had grown long and matted—doubtless added to his mother’s upset). Matters came to a head when one day his mother became very demonstrative and the young sage not only totally ignored her, he stood up (a rare enough thing in itself) and walked away. His mother gave up and left. (She would return, eighteen years later, along with Ramana’s older brother, and become his disciple. At her death in 1922 Ramana declared her ‘liberated’).As Arthur Osborne pointed out this whole sequence is reminiscent of the scene in the New Testament where Jesus is reputed to have not recognized his mother, implying that he had gone beyond the ‘small family’ to become a full member of the ‘cosmic family’ of the totality of all. Only one who is radically awakened can make such a claim, indicating that they have broken all familiar attachments, and in particular, the attachment to form (essentially, the gross body and its gene pool; i.e., the nuclear family). Here again the fine line between radical awakening and mental illness is seen (a fascinating study in itself, and one tackled to some extent by the brave Scottish psychiatrist R.D. Laing in the early 20th century). Many mentally ill people have ‘disconnected’ from family for endless possible reasons and remained ‘unresponsive’ in the face of family members attempting to re-establish connection or human intimacy. Brahmana Swami’s state was not ill, however. He still had certain lessons to learn around caring for his body, if only so that he could adequately guide others, but his state was one of bliss and deep peace (something even tangibly felt by others merely by sitting in his presence). That is not the state of a mentally ill person, but rather one who has transcended egocentric contraction and pain.

In 1899

Brahmana Swami, now 20 years old, abandoned the nearby temples and began living

in various caves found in Mt. Arunachala. (Though called ‘Mt.’, it is really

only a broad, flattened hill, not even 3,000 feet high, though it has a large

ground circumference of some eight miles, used traditionally by pilgrims to

make circumambulations of). He would remain in these caves for some

twenty-three years; although not, strictly speaking, in seclusion, as he always

had attendants and disciples around him. In 1907, an accomplished Vedic scholar

named Sri Ganapati Sastri visited Brahmana Swami and joined his slowly growing group of disciples, while at the same time bestowing on the 28 year old sage the name Bhagwan Sri Ramana Maharshi. 'Bhagwan' is an honorific meaning, roughly 'Lord'; 'Maharshi' means 'great sage'. 'Ramana' was a shortened version of his birth name Venkataraman. Ramana accepted the name and was known mostl as 'Bhagwan', 'Sri Ramana', or 'the Maharshi' for the rest of his life.

In

1922, aged 43, Ramana left the caves and relocated at the foot of the mountain.

An ashram was gradually built around him. He remained there for the last

twenty-seven years of his life, teaching a steady stream of visitors from far

and wide, sometimes with pithy verbal discourse or question and answer

sessions, but more often through his powerfully illumined silent presence.

Teachings

Although

relatively long books have been written about Ramana’s teachings, in fact what

he taught is supremely simple. He taught that our true nature is the

transcendent, impersonal and universal Self, and that we merely suffer from a

type of ignorance or mental confusion that prevents us from seeing this. His

prime method for uncovering this true nature was via Self-enquiry, the

relentless posing of the essential question ‘Who am I?’ This is a Zen koan (and in fact, there are striking

similarities between Zen master Hakuin and Ramana, although their outer

dispositions appear to have been very different—Hakuin aggressive and

confrontational, Ramana outwardly gentle and largely passive, although he did,

on occasion, challenge seekers).

Attaining to Self-realization via usage of Self-enquiry needs to be understood. As Ramana taught, the primal thought, the ‘I’, is to be penetrated entirely. Initially when we look within we will find this ‘I’-thought readily enough. It is the standard sense of ‘I am-ness’ that most people are aware of, even if only vaguely. However, Self-enquiry is not about resting in this I am-ness, because that is really just the conventional self—the ego—observing itself. We need to go further, beyond the conventional sense of I am-ness, and see what is ‘behind’ that; or more accurately, prior to that. What is prior to that is the ‘true I’, or ‘I-I’ as it is sometimes referred to as.

Ramana

taught that the main cause of our ignorance of the true Self is our

identification with the physical body, and with being a separate entity in

general. The true Self is not identified with the body, and is not, strictly

speaking, located within time or space. Because it is timeless, it is therefore

bornless and deathless. Nor can it be truly known via thought. Obviously, we

can think about the true Self, and we

can even imagine it, but what we are

thinking about and what we are imagining is only a thought or imagination; it

is not the true Self. This is

essentially identical in meaning to the famous line from the Tao Te Ching, ‘The Tao that can be told

is not the eternal Tao; the name that can be named is not the eternal Name.’

We can allow the translators of the Tao Te Ching some liberty, but strictly speaking the Tao (the true Self) is not ‘eternal’, as that implies a state within time; rather it is timeless. Ramana taught that this ‘timeless’ is not some special state existing outside of the ‘real universe’ or any such thing. It is rather that the timeless is the Real. It is only because of our confused and deluded state, brought about mostly by our identification with the body, that we conceive of time as objectively real, when in fact it is a mental construct, something we have, in essence, ‘made up’.

Ramana further taught that it is not only ‘time’ that we have made up. We have made up everything, including our bodies—the gross (physical or ‘waking’), the subtle (higher energy frequency, or ‘dream body’) and the causal (highest frequency, or ‘deep sleep’). To awaken fully to the true Self is to ‘dissolve’ our identification with all three bodies; that is, to be liberated into the formless.

The method of Self-enquiry is not a process of intellectual investigation. It rather involves keeping the attention on the ‘I’ with great determination and consistency. However, Ramana did teach an alternate approach, that of surrender to the Divine (bhakti Yoga). This approach could be said to be more appropriate for those emotionally inclined, or those who find the direct approach of Self-enquiry not appropriate for them. Ramana did teach that both approaches ultimately lead to the same thing, realization of the true Self.

Ramana’s

highest teaching was via silent transmission. The question of whether or not a

guru can actually ‘transmit’ wisdom or realization has long been debated, but

the whole issue was perhaps best summed up when a young U.G. Krishnamurti (not

to be confused with his more famous namesake J. Krishnamurti) visited Ramana in

1939 and asked him if he could transmit his wisdom. ‘I can’, replied Ramana.

‘But can you receive it?’ It’s the perfect reply, because although wisdom

cannot be ‘sent’ to another person like a piece of mail, it can be radiated in

that person’s presence. It is then simply a question of whether or not the

seeker can allow his or her own innate wisdom to respond to that radiance, that presence which is manifestly

embodied by a deeply awakened teacher.

Perhaps a perfect example of Ramana’s teaching style was given when a seeker once asked him, ‘How to control the mind?’ to which Ramana replied, ‘What is the mind? Whose is the mind?’ When the seeker countered with ‘I cannot control my mind’, Ramana responded with ‘It is the nature of the mind to wander. You are not the mind...never mind the mind. If its source is sought, it will vanish, leaving the Self unaffected.’ The seeker tried a different angle, asking ‘So one need not seek to control the mind?’ Ramana, with laser-like precision, answered ‘There is no mind to control if you realize the Self.’

He also

taught that the world we typically perceive arises only with the mind. For

example, every night we go to sleep. In deep dreamless sleep, there is (in our

experience) no body and no world. It is only when we wake up in the morning and

the mind resumes its activity that the world we perceive springs back into

existence for us. Our perception of this world is such an enormous distraction

that it effectively blocks us from awareness of the Self. To penetrate the

illusion of the false self—the conventional ‘I’ (ego) that upholds the

perception of the world—is to awaken to the Self, and finally to understand

that the world we experience is not separate from the Self. That is, nothing

truly exists but the Self, or pure Consciousness.

It may be noted by the attentive reader that these teachings sound suspiciously similar to some of the problems touched on in Chapter 2 (Eastern Fundamentalism), such as the facile (and easily misused) view that ‘only Truth (the Self) is real’, or put another way, ‘you are already enlightened’. But the crucial difference with a master of Ramana’s calibre is that he himself has truly realized this state, and thus what he says is not empty doctrine or dogma. He himself is a living scripture, and speaks only from his direct experience. And so to be with Ramana was to undergo darshan in the truest meaning of that word—‘to be in the light of the master’—which for the seeker, is the same thing as a plant being nurtured by the rays of the Sun. Ramana was not just passing on doctrinal truths; he was the doctrinal truth.

The same applied to Ramana’s teachings on the matter of free will. Asked once if a person had free will, he pointed out that the question is only relevant for one who still believes they are a separate person. From the point of view of absolute truth, there is no separate person, and therefore questions about whether or not ‘the person’ has free will automatically drop.

That entire idea, if taught by one who has not directly realized that the discreet separate ego-identity is ultimately unreal, will simply be dogma, and if taken on by one who has not realized their greater nature, can easily be corrupted into excuses to not be responsible, and so forth. (‘Free will is an illusion, so why bother doing anything?’). Again, the matter depends on who is teaching it. Ramana could teach such principles of ultimate truth effectively, because he himself was the living answer.

Ramana

taught tirelessly into his late 60s until his health began to fail due to

cancer that appeared in one of his arms. Despite several operations, the cancer

kept reappearing. Doctors advised that the arm be amputated, but Ramana

refused. He passed away as he had lived—with great serenity, and surrounded by

hundreds of deeply devoted disciples—on April 14, 1950, at 70 years of age.

His

legacy lives on, and as with many great sages has become more pervasive over

time. By the early 1990s in particular Ramana’s life and teachings, already

respected worldwide by sincere seekers, grew in stature and fame, especially in

Europe and North America. This was largely due to the work of H.W.L. Poonja

(1910-1997), an Advaitin master living in Lucknow (in north central India), who

had spent a few years with Ramana in the 1940s and underwent a deep awakening

in the sage’s presence. Poonja subsequently lived and taught quietly to a small

circle of students until the American seeker Andrew Cohen discovered him in the

mid-1980s. Although Cohen later broke with Poonja, he had energetically

promoted Poonja’s name in the West. Hundreds of seekers then made their way to

Poonja, and thousands more subsequently become aware of Poonja’s guru, Ramana,

via the work of a whole new generation of Western satsang teachers endorsed by

Poonja and a plethora of newly published books on Ramana, Poonja, and

Advaita. Many leading edge thinkers in

the field of human transformation regard Advaita as a major potential light

leading forward into a more awakened future in general, in large part because

of the remarkable simplicity of Advaita and the universality of its

principles—and in no small part because of the impeccable example set for it by

its greatest modern exponent, the sage of Arunachala.

That said, it would be remiss to not point out that Ramana himself never actually claimed to be a guru and never claimed to be part of, let alone start, any ‘lineage’. The fact that a number of modern satsang teachers (most of them students of Poonja) have claimed Ramana as part of their lineage must be seen as their own doing, and not reflecting on anything initiated by Ramana. Unlike Jesus, Ramana did not go seeking disciples to make them ‘fishers of men’—he simply sat there and people eventually gathered around him. His whole life and work remained an uncompromising testament to an exquisite solitude that was yet openly available to others—much like his beloved mountain.

________________________________

Nisargadatta Maharaj: Passionate Tiger

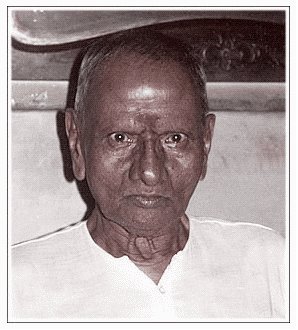

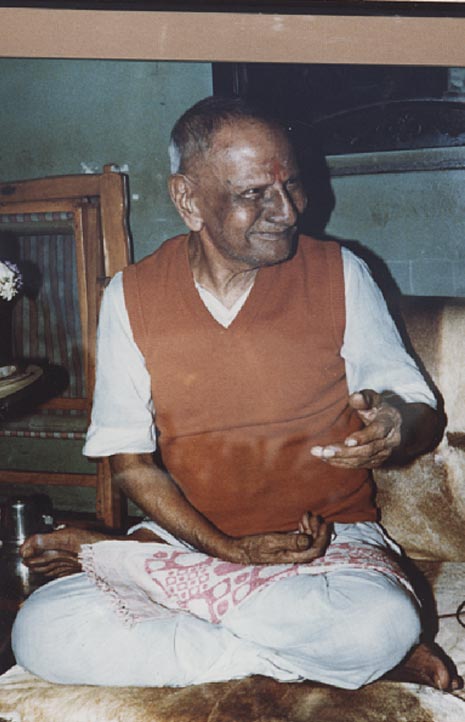

Nisargadatta

Maharaj makes for an interesting contrast with the previous great sage

discussed, Ramana Maharshi. This is because although they taught essentially

the same thing—the very highest truths of the great wisdom tradition known as

Advaita—they were remarkably different expressions of that truth. In some ways

Nisargadatta and Ramana were opposites, something hinted at even in the many

photos of them. As gentle, reticent, and quietly powerful as Ramana was, Nisargadatta

was fierce and vocal. As rural as Ramana was (living by a mountain),

Nisargadatta was urban, teaching out of a small home in a huge metropolis (Bombay,

now known as Mumbai) surrounded by millions of people. As detached and

unworldly as Ramana was, Nisargadatta was engaged and ‘ordinary’, marrying,

raising a family, and working for many years to support them via running a

simple retail trade (selling household goods; mainly Indian cigarettes). As

much as Ramana’s entire life was devoted to living and teaching from the

Self-realized state (he had awoken at just 16), Nisargadatta did not begin

seeking until age 36, and had his awakening a few years later. And as much as

Ramana had no human teacher, Nisargadatta did (the guru Siddharameshwar Maharaj, 1888-1936), and would later

credit his awakening as due to simply following his guru’s instructions.

(Although Nisargadatta did not talk about it much, in his later years he did

state that he was part of a teaching lineage via his guru, known as the Navnath

Sampradaya, a semi-mythological lineage of Hindu mystics).

Nisargadatta

Maharaj makes for an interesting contrast with the previous great sage

discussed, Ramana Maharshi. This is because although they taught essentially

the same thing—the very highest truths of the great wisdom tradition known as

Advaita—they were remarkably different expressions of that truth. In some ways

Nisargadatta and Ramana were opposites, something hinted at even in the many

photos of them. As gentle, reticent, and quietly powerful as Ramana was, Nisargadatta

was fierce and vocal. As rural as Ramana was (living by a mountain),

Nisargadatta was urban, teaching out of a small home in a huge metropolis (Bombay,

now known as Mumbai) surrounded by millions of people. As detached and

unworldly as Ramana was, Nisargadatta was engaged and ‘ordinary’, marrying,

raising a family, and working for many years to support them via running a

simple retail trade (selling household goods; mainly Indian cigarettes). As

much as Ramana’s entire life was devoted to living and teaching from the

Self-realized state (he had awoken at just 16), Nisargadatta did not begin

seeking until age 36, and had his awakening a few years later. And as much as

Ramana had no human teacher, Nisargadatta did (the guru Siddharameshwar Maharaj, 1888-1936), and would later

credit his awakening as due to simply following his guru’s instructions.

(Although Nisargadatta did not talk about it much, in his later years he did

state that he was part of a teaching lineage via his guru, known as the Navnath

Sampradaya, a semi-mythological lineage of Hindu mystics).

According to Nisargadatta’s well known disciple Ramesh Balsekar, Nisargadatta was scornful of biographical information about his life. He once remarked to Ramesh with his characteristic bluntness, ‘Instead of wasting your time on such useless pursuits, why don’t you go to the root of the matter and enquire into the nature of time itself?’ It is perhaps for that reason that not much is known about his earlier years. As with many Indian sages the name he came to be known by was not his birth name. He was born Maruti Shivrampant Kambli, on April 17, 1897, in Bombay, one of six children born to a pious Hindu couple.9 Maruti was raised in the country, in a small village. When he was 18 his father, a farmer, died; Maruti then moved to Bombay, following his elder brother, so as to work and help support his family.

Growing up, Maruti had worked assisting his father on the farm, and had not received a traditional education. Despite that he was bright and inquisitive. His first spiritual influence was a friend of his father’s, a pious Brahmin who would often engage the young Maruti in discussion about philosophical and religious matters. This seed, planted in his boyhood, would later bloom into his passionate dedication to the highest truths of life. In the mean time his responsibilities lay elsewhere. After arriving in Bombay he worked as a junior clerk, but apparently hated the job and quit after a few months. It’s possible that he had a headstrong nature and needed to be his own boss. This seems likely as he soon started his own business, selling children’s clothing and Indian cigarettes (usually called ‘beedies’—which accounted for the later informal name sometimes heard to describe him, that being ‘Beedie Baba’).

Maruti’s business prospered and he was eventually able to open a few more shops. The relative financial stability brought by this allowed him to settle down. At age 27 he married a woman named Sumatibai, and went on to have four children (three daughters and a son) with her. His life up until his mid-30s was routine and very typical for a hard working family man in the city. However he did have one friend who was unusual, a dedicated spiritual seeker who happened to be a disciple of a somewhat obscure Hindu guru named Siddharameshwar Maharaj. (One has always to bear in mind that ‘gurus’ are very common in India; practically every village has its local sage, and major cities have many religious priests, spiritual teachers, and wandering mystics of all conceivable levels of quality. Few, however, could be said to be deeply realized).

On a fateful day in 1933 Maruti went with his friend to see the guru, and was strongly impacted. One might wonder if this was due to the quality of the guru, or to the fact that Maruti had been unconsciously seeking something and was primed to break out of his routine psychological rut, into a higher consciousness. Probably both are true. Regardless of Maruti’s level of readiness, he was sufficiently impressed by Siddharameshwar to dutifully follow the guru’s spiritual instructions, which consisted of a mantra and a guidance to seek his true Self. This took the form of a constant remembrance of the thought-feeling ‘I am’. (In essence, very similar to the ‘self-remembering’ taught by the famed Greek-Armenian sage G.I. Gurdjieff in the early 20th century).

The guru had said to Maruti, ‘You are not what you take yourself to be’. That is the ultimate pointer toward higher truth, and the time-honoured rallying cry of genuine mystics and Self-realized sages everywhere. It is what shakes a seeker, or a potential seeker, out of the conventional slumber of typical life, where we (remarkably) come to take for granted mediocrity, that we should somehow be satisfied with what has been put in front of us. Truth-seekers throughout history have had to work against the grain of convention, and frequently against an unspoken taboo not to challenge these conventions, foremost of which seems to be the consensual agreement that you are what you take yourself to be. It may be confidently said that no movement toward Reality can occur until we first begin to challenge that assumption. I am not what I take myself to be is the beginning of awakening, the first glimmer of light upon a murky inner landscape.

To receive quality guidance or specific instructions from a reasonably worthy spiritual teacher is not uncommon. What is uncommon, however, is to set about following those instructions with great determination and faith in the teacher’s guidance. And that is exactly what Maruti did. It is here where he shows his latent quality, in a way that immediately marks him apart from the vast majority of truth-seekers everywhere. For even though Maruti had work and family responsibilities, he still set aside time every evening to retire to a special loft he had constructed in his home to practice his guru’s instructions with great commitment.

Maruti did not have long with his guru, only about thirty months. Siddharameshwar died in 1936, leaving his determined student on his own to complete his realization. Maruti resolutely stayed with the practice of remaining focussed on the ‘I am’ awareness, and this began to yield clear results. He awoke deeply to his true nature as the Self, and then decided to take a spiritual name—‘Nisargadatta’—which means ‘one who dwells in the natural state’. The second name, ‘Maharaj’, is an honorific meaning ‘great king’ and would be affectionately bestowed on him in later years by his disciples. For most of his later teaching career he was referred to as ‘Maharaj’.

It is interesting to note that not long after his awakening Nisargadatta temporarily left his family and work, deciding to wander as a mendicant throughout India. He did this for about a year, at age 40, before coming to the realization that the life of a homeless mystical sadhu was not for him. He then returned to Bombay and his family, and resumed his work as a shopkeeper. He would remain there for the final forty-four years of his life.

Nisargadatta’s wife passed away in 1942, and he spent the following decade working and completing the duties of raising his children. He did not begin formally teaching and taking disciples until age 54. The fact that he spent fifteen years as a realized sage, but did not take students, is testament to his humility. Far too many teachers (especially in the West in modern times) assume a teaching function with minimal time to mature their spirit after an initial awakening (or even without one). It is never hard to find students or followers for a sufficiently charismatic (and hopefully awakened) person. It is far more uncommon to find an awakened individual spending many years living quietly and responsibly, slowly honing their understanding, before assuming a teaching role.

His children now adults and on their own, Nisargadatta began his formal teaching work in 1951 (which was the year after Ramana had died—as one great teacher departed, another one appeared). He did this out of a small room on the upper floor of his Bombay home, where he taught for some thirty years. For his first fifteen years of teaching he continued to run his retail shops. He retired from work in his late 60s, but continued to teach until his death from cancer on September 8th, 1981, aged 84.

Teachings

Nisargadatta did not teach the lazy man’s way to enlightenment. He was a fierce teacher who had much more in common with the old Chinese and Japanese Rinzai Zen masters and the path of ‘sudden awakening’. The fact that he himself had attained Self-realization in a relatively short time (under three years of intensive meditation practice) no doubt shaped his teaching style. There are many stories of his passionate approach, his bluntness and ruthlessness, and his seeming lack of patience with lazy students or seekers who were merely ‘spiritual tourists’ come to see the latest guru. All of this is clear enough in surviving videos of some of his talks and interactions with students. One can see from these videos, mostly recorded when Nisargadatta was already in his 80s, his fiery nature, as well as his obvious passion. His manner was diametrically opposite to Ramana Maharshi’s serenity.

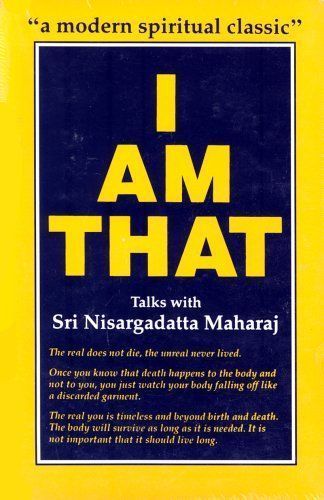

Nisargadatta’s

student Maurice Frydman, a Polish Jew who had once lived at Mahatma Gandhi’s

ashram, recorded a series of Nisargadatta’s talks, translated them from Marathi

(Nisargadatta spoke no English), and published them in 1973 as the book I Am That. This book went on to achieve

classic status, having a strong influence on many young Western seekers during

the 1970s and 80s. The main quality of the book is the direct forcefulness of

Nisargadatta’s presence, and the uncompromising clarity of his answers to

questions put to him. A number of seekers over the years would report that

they’d had profound openings and even direct awakening experiences merely by

reading the book. More than one seeker claimed that the book itself was a

legitimate spiritual transmission. (As any writing can be, if coming from an

awakened consciousness and read by a receptive and ready reader. And as an

amusing side-note, I once was in a bookstore and saw a book credited to Ramana,

titled Who are You?, paired side by

side and appropriately ‘answered’ by Nisargadatta’s I Am That).

Nisargadatta’s

student Maurice Frydman, a Polish Jew who had once lived at Mahatma Gandhi’s

ashram, recorded a series of Nisargadatta’s talks, translated them from Marathi

(Nisargadatta spoke no English), and published them in 1973 as the book I Am That. This book went on to achieve

classic status, having a strong influence on many young Western seekers during

the 1970s and 80s. The main quality of the book is the direct forcefulness of

Nisargadatta’s presence, and the uncompromising clarity of his answers to

questions put to him. A number of seekers over the years would report that

they’d had profound openings and even direct awakening experiences merely by

reading the book. More than one seeker claimed that the book itself was a

legitimate spiritual transmission. (As any writing can be, if coming from an

awakened consciousness and read by a receptive and ready reader. And as an

amusing side-note, I once was in a bookstore and saw a book credited to Ramana,

titled Who are You?, paired side by

side and appropriately ‘answered’ by Nisargadatta’s I Am That).

On the jacket of I Am That is the line, ‘The real does not die, the unreal never lived’. We can contrast that with a well-known line from the mystical text A Course In Miracles: ‘What is real cannot be threatened, what is unreal does not exist’. This is one of the classic refrains of Advaita-based teachings, and it was the central point that Nisargadatta drove home over and over again in thirty years of teaching. When his guru had said to him, ‘you are not what you take yourself to be’, he was preparing Nisargadatta for that essential realization, which ultimately became his main teaching tool.

Similar to Ramana, Nisargadatta did not exclusively teach Self-remembering or Self-enquiry, both of which are part of the path of jnana yoga (realization of the Divine via mental discipline and penetrating insight). If he felt that a seeker’s temperament warranted it, he would advise them to follow a path of devotion (bhakti yoga). Regardless of the choice made to follow whichever path, Nisargadatta taught (paradoxically) that at the ultimate level there is no such thing as ‘free will’ or a ‘doer’. He said that the mind and body, created as they have been by endless preceding causal factors, are merely mechanical. The mind has the ability to create the illusion of being a ‘doer’ or a ‘chooser’, but in fact it is ‘doing’ and ‘choosing’ based purely on past causes. The true Self actually does nothing, being merely a silent witness to all that is arising in the field of consciousness.

Accordingly, there is ‘doing’ but there is no ‘doer’. There is walking, but no walker. There is reading, eating, and sleeping, but no reader, eater, or sleeper, and so forth. To see directly into the illusion of the wilful doer is the same as seeing into the illusion of the false self, the separate personality. There is always only functioning occurring, but no actual ‘entity’ behind the scenes pulling levels to make things happen. Because there is no actual doer, the questions of ‘bondage’ and ‘liberation’ are therefore rendered meaningless. For who is there to be in bondage? And who is there to achieve liberation? The whole idea of enlightenment, or any sort of ‘spiritual path’, is rendered meaningless once we grasp the essential truth, that there is no discreet entity that is ‘me’ to attain any such thing—and nor is there any discreet entity that is ‘me’ to suffer miserably. We suffer only because we are caught in a deep illusion in which we appear to exist as distinct entities.

As touched on in the last chapter, all these ideas have become well known amongst sincere Western seekers in recent years, especially those who have studied some Advaita (or Buddhism). All of them are easy to misunderstand and misuse. The idea of there being ‘no doer’ is extremely susceptible to a confused interpretation and to being hijacked by the ego. It needs to always be born in mind that when sages like Ramana or Nisargadatta speak of there being no real personality, or no actual doer, they are speaking from the perspective of one who has put enormous effort into coming to that realization. Ramana may have awakened in one thirty minute burst of intense focus and longing for truth, but he subsequently spent many years sitting in solitary meditation, sometimes in dark and miserable vaults, almost starving his body, perfecting his clarity and wisdom. Nisargadatta spent nearly three years meditating many hours—‘all my available time’ was how he put it—without fail, making stupendous concentrative efforts. And so while these sages ultimately saw into the illusion of the personal self and free will, they only got to that place of clarity by making profound effort—and an effort that was, above all, full of a burning passion for truth. No less is required of us for the same realization. There is no free pass to awakening. To merely ‘know’ that there is no separate self, or wilful doer, and yet to not attempt to directly realize this—to summon no effort or burning passion to truly see and know this—is worse than useless, because we run the risk of dreaming that we are awake, or aborting our own awakening, or worse, misleading others by a cynical ‘I’ve heard those ideas before and they don’t work’ attitude.

Nisargadatta had some interesting angles on the subject of ‘time’. Consistent with most realized sages he spoke about the essential illusion of time as we typically experience it. However he added a deeper piece, that being that not only is ‘past’ and ‘future’ nothing more than a construct of the mind, so is ‘present’. As he put it, the present is never truly present because it ‘never stays still’. He rather pointed to a deeper element found within pure consciousness, which Ramesh Balsekar translated as ‘intemporality’ (timelessness). Nisargadatta then added that as we normally experience ourselves to be, we are time—that is, we exist entirely as illusory separate selves by defining ourselves within the field of illusory time.

This does not require too much thought to see. We normally define ourselves on the basis of our memory, our accumulated life experience. Things like ‘maturity’ or ‘wisdom’, in the conventional sense of those words, are based entirely on accumulated memory. Who we know ourselves to be, in the usual sense of that, is all memory-based. And so our basic identity—literally, ‘who I am’ (in the conventional sense)—is, in essence, nothing more than time itself.

One sign of a deeply awakened sage is that they will often surprise a seeker by phrasing things with great originality, or in unexpected ways. Nisargadatta was famous for this. A good example follows, excerpted from I Am That:

Q: Are awareness and love one and the same?

Nisargadatta: Of course. Awareness is dynamic, love is being. Awareness is love in action. By itself the mind can actualize any number of possibilities, but unless they are prompted by love they are valueless. Love precedes creation. Without it there is only chaos.

The comment ‘awareness is love in action’ may at first glance seem strange; we are not accustomed to associating awareness with ‘action’. Predictably the student wonders about this, and gets ‘hit’ with a Zen stick by Nisargadatta.

Q: Where is the action in awareness?

Nisargadatta: You are so incurably operational! Unless there is movement, restlessness, turmoil, you do not call it action. Chaos is movement for movement’s sake. True action does not displace; it transforms. A change of place is mere transportation; a change of heart is action. Just remember, nothing perceivable is real. Activity is not action. Action is hidden, unknown, unknowable. You can only know the fruit.

The teaching there is profound and especially relevant for our modern hectic times. The lives of most people are full of empty activity; restless motion that accomplishes little. Nisargadatta is pointing out that ‘true activity’ arises from within, as a function of consciousness, of presence, of mindfulness.

Q: Is not God all-doer?

Nisargadatta: Why do you bring in an outer doer? The

world recreates itself out of itself. It is an endless process, the transitory

begetting the transitory. It is your ego that makes you think there must be a

doer. You create a God in your own image, however dismal the image. Through the

film of your mind you project a world and also a God to give it cause and

purpose. It is all your imagination—step out of it.10

Nisargadatta: Why do you bring in an outer doer? The

world recreates itself out of itself. It is an endless process, the transitory

begetting the transitory. It is your ego that makes you think there must be a

doer. You create a God in your own image, however dismal the image. Through the

film of your mind you project a world and also a God to give it cause and

purpose. It is all your imagination—step out of it.10

And here Nisargadatta echoes the wisdom of all awakened sages, which is that the entire perceivable universe is both arising in the field of our awareness and is interdependent with it. What we commonly take to be real is in fact a function of our mind and its projections. Our task is to seek out the Real, and this is done by penetrating into the mystery of ‘I am’.

Although

like most Advaitin sages Nisargadatta taught that our real nature is already

whole and complete, he did not teach a passive acceptance of this. He taught

that until one realizes one’s true nature, one should continue with sadhana (spiritual practice) until free

of the delusion that one is not already enlightened. This of course is a subtle

point and is easily misused. Our task as sincere

seekers is to respond fully to the wise counsel of a master like Nisargadatta,

and continue with our practices without expectation or attachment to outcome.

_________________________________________________

Yaeko Iwasaki: Deathbed Awakening

Yaeko

Iwasaki (1910-1935) is one of the more obscure and unlikely mystics of history.

The story of her radical awakening at a young age while on her deathbed is

extraordinary. In the English language her story is recorded, to my knowledge,

in only one book. That book just so happens to be one of the two or three most

famed books on Zen Buddhism ever written, the American Zen master Roshi Philip

Kapleau’s The Three Pillars of Zen

(first published in 1965).11 Kapleau (1912-2004) had been a court

reporter at the Nuremburg War Trials in 1945. From 1953 to 1965 he trained

under several Zen masters in Japan, later returning to America where he founded

what was to become one of the more influential American Zen schools, in Rochester,

New York.

Yaeko

Iwasaki (1910-1935) is one of the more obscure and unlikely mystics of history.

The story of her radical awakening at a young age while on her deathbed is

extraordinary. In the English language her story is recorded, to my knowledge,

in only one book. That book just so happens to be one of the two or three most

famed books on Zen Buddhism ever written, the American Zen master Roshi Philip

Kapleau’s The Three Pillars of Zen

(first published in 1965).11 Kapleau (1912-2004) had been a court

reporter at the Nuremburg War Trials in 1945. From 1953 to 1965 he trained

under several Zen masters in Japan, later returning to America where he founded

what was to become one of the more influential American Zen schools, in Rochester,

New York.

Yaeko was just a girl in most respects, in frail health, who developed a spark of interest in Zen and deep awakening. And yet the ‘spark’, and in particular how she responded to it, is of great importance and in many ways lies at the heart of the awakening process. The birth of the ‘spark’ is always a mystery; it is more what is done with it that matters. To experience the spark of enthusiasm for awakening is not entirely uncommon. What is extremely uncommon is to tackle it with gusto, all the more so for a young person who is physically unwell.

Yaeko was guided through her awakening by the well known Zen master Roshi Sogaku Harada (1870-1961). He was one of Roshi Kapleau’s main teachers, and had a reputation for being amongst the fiercest of 20th century Japanese Zen masters. His monastery was renowned for the harsh climate—both the outer weather, and in inner austerity and discipline. Harada, much like his great forbearer Hakuin, was a lion, not a polite Oriental priest. Although he worked within the structure of an old tradition (and even worked for many years as a university professor as well) he was unrelenting in his dealings with his Zen students, never compromising when it came to the matter of ultimate truth.

This latter quality of Roshi Harada was important, because in guiding Yaeko he had to summon great courage in face of the fact that she was very ill, possibly on death’s doorstep (which turned out to be the case). It is more than tempting to ‘be gentle’ with one who is very sick; indeed it is almost a moral imperative. However a deeply awakened sage can see beyond moral constraint, recognizing a bigger fish to fry. (That, granted, is a grey area, and more than one guru supposedly ‘beyond moral constraint’ has is in fact turned out to have exercised poor judgment, but that is an entirely separate study).12

Yaeko began practicing zazen (Zen meditation) at the age of 20. She continued to practice with great diligence and passion for truth for the next five years. Then, in a dramatic deepening of insight that unfolded in five fascinating days, she reached a very advanced level of realization before her body succumbed to chronic illness a week later at age 25. Concerning her passing, Roshi Kapleau made an interesting observation. He wrote,

In India she would undoubtedly have been heralded as a saint…in Japan the story of her intrepid life and its crowning achievement is scarcely known outside of Zen circles.13

What is of note about Kapleau’s remark is not the relative degree of Yaeko’s renown, but the fact that her story was known in any circles at all. Here in the West, especially if there had been no Christian basis to her awakening, if her story had been known at all it probably would have been marginalized, or dismissed entirely as a mere ‘altered state of consciousness’ brought on by her illness and looming death. In other words, her experience probably would have been pathologized.14

Yaeko’s awakening is documented in a series of remarkable letters written to her master, Roshi Harada, in 1935. Kapleau called these letters ‘eloquently revealing of the profoundly enlightened mind’ and ‘abounding in paradox and overflowing with gratitude, qualities which unfailingly mark off deep spiritual experience from the shallower levels of insight.’15 What is also remarkable about the letters is that Yaeko is deeply honest, and continually ‘busts’ herself on her pride as it pops up, unexpectedly, with each deepening of her clarity. Roshi Harada had these letters published after her death in a Buddhist journal in 1936, and added the commentaries that he’d jotted down in the margins of the letters when reading them, for the sake of other readers. Yaeko never had the chance to read these comments, but they are extremely useful for any seeker to study, and can be taken as the old master guiding his student through, amongst other things, the thickets of what Chogyam Trungpa would later call ‘spiritual materialism’ (the tendency of the ego to hijack spiritual experiences and try to claim them for its own purposes). The exchanges between the Roshi Harada and Yaeko were subsequently published privately in 1937 by the Iwasaki family in a book titled Yaezakura (‘double cherry blossoms’).

Yaeko was no wandering street mystic, or materially underprivileged. In fact she was a ‘rich kid’, born into the Mitsubishi family dynasty. As a toddler she suffered from a serious life-threatening illness that she survived but which left her with a heart condition. Growing up she received a scholastic education (in which she excelled) and preparation for marriage and motherhood, consistent with Japanese tradition in the early 20th century. However, at 20 years of age, she fell ill and was diagnosed with tuberculosis. Under doctor’s orders she mostly retired to her bed for the next couple of years. Around this time her father was also diagnosed with a serious heart condition. Gripped by fear of his looming mortality he sought out a Zen master, found Roshi Harada, and apprenticed himself to the old sage. After a year of committed practice he experienced his first kensho (awakening). Re-invigorated, he resumed his duties at Mitsubishi, but not longer after his heart suddenly gave out and he passed on. Yaeko, deeply attached to her father, was profoundly moved, and opted to devote her own life to the study and practice of Zen, under the same master, Roshi Harada.

Yaeko was not alone in this; remarkably, her mother, as well as her two sisters, also devoted themselves to Zen study and practice under the Roshi. (It is highly unusual for an entire family to engage in serious spiritual discipline; more commonly there is one ‘black sheep’ who seeks wisdom, often to the consternation of the rest of their family, as in the case of Ramana). Yaeko was assigned the classic koan known as Mu. This stems from an old Chinese Cha’an Buddhist koan, ‘Does a dog have Buddha nature?’ to which the answer is given ‘Mu!’ The word translates approximately as ‘no’ or ‘not’, but this ‘no’ should not be understood as literal or straightforward negation. All Zen koans, when successfully ‘solved’, involve the transcendence of limited, conventional thinking, and breakthrough into a non-dual perspective—that is, glimpsing the interconnectedness, and primal unity, of existence and all apparent ‘things’ within it—and in particular, the illusory nature of the split between self and what self is perceiving.

Yaeko not only dove deep into concentrated and sustained koan practice, she also studied assiduously, reading the 13th century Zen master Dogen’s classic Shobogenzo text not once, but seventeen times. (The Shobogenzo—the word means ‘Treasury of the Eye of the True Dharma’— is a collection of ninety-five essays that cover the gamut of outer spiritual life and inner experience for a Zen practitioner). After a period of time her tuberculosis went into remission and then passed. Although her body was weakened by the ordeal, she continued to practice and after several years, in December of 1935, she had her first profound awakening. When she died of pneumonia shortly after, she was in a state of deep serenity; so much so, that the attending doctor remarked that ‘never have I seen anyone die so beautifully’.16

The letters from Yaeko to her teacher are covered in seventeen brief pages of Kapleau’s work. The first letter was dated December 23, 1935; the last is December 28. During these five intense days she passed through progressively deeper stages of realization. Roshi Harada was not able to guide her in person; he had just left her side on December 22, after visiting her (though he returned a week later, and was with her when she died). What is impressive about her letters is that she very clearly guides herself through the thorns of the spiritualized ego, which attempts to hang on even as realization is deepening.

Yaeko’s awakening process began with an original ‘hazy glimpse’, which motivated her to search deeper. She had a breakthrough on December 22, in which she claimed that the ‘ox’ had suddenly come much closer—‘a hundred miles nearer’. She was seeing something clearly; but at the same time, the spiritualized ego reared its head, and she remarked, ‘even you, my Roshi, no longer count for anything in my eyes’, although she hastily followed that up with expressing deep gratitude.

To dismiss one’s teacher, in however subtle fashion is a fairly common sign of early-stage awakening. It is natural, in the rush of an initial deep understanding, to want to stand forth and proclaim independence. Almost always, however, such a position is entirely premature, because the initial awakening, however impressive, is usually but a glimpse. Even in the case of rare profound and deep sudden awakenings, such as Ramana Maharshi passed through, it is followed up by years of sustained meditation to clarify and deepen the original realization.

Yaeko followed her expression of gratitude by writing about the abundant sense of joy that was arising in her. She then wrote a significant thing:

Now that my mind’s eye has been opened, the vow to save every living being arises within me spontaneously. I am so beholden to you and to all Buddhas. I am ashamed [of my defects], and will make every effort to discipline my character.

Awareness of what remains to be ‘cleared up’ becomes intensified with early awakenings; this awareness is sometimes called ‘remorse of conscience’, and can be likened to a ‘searing inner pain’ based on direct realization that any harmful actions we have done to others is no different from inflicting it on ourselves—because others are ourselves.

At this point Roshi Harada commented that although Yaeko has ‘seen the Ox clearly’ she is still a long way off from grasping it, as her thinking is still obscuring the deeper truth. (It is here that the Roshi marks himself as a skilled master. A lesser teacher would have more of a tendency to immediately sanction any sort of awakening, and even, on occasion, to bless the seeker and encourage them to teach). Roshi Harada further comments that there are three clear signs that Yaeko’s initial awakening is genuine: she feels a desire to help others, she feels a deep sense of inner confidence around her realization, and she is determined to apply strong discipline to her further purification and understanding. Despite that, he concludes that she has a long way to go because she is still entrenched in the subject-object division. As he says, ‘as yet there remains a subject who is seeing…she must search more intensely!’ That is, she is still very much in the position of a separate self who is ‘having a spiritual experience’.

Two days later, on December 25, Yaeko had a deeper breakthrough. She wrote enthusiastically to the Roshi, declaring that she had ‘attained great enlightenment’ that left her full of joy and ecstasy. (Her progress at this point was compared to ‘grasping the Ox’, which is stage four in the Ox-herding pictures). Roshi Harada confirmed that she had indeed had a legitimate realization of the Buddha-mind (true nature). Yaeko wrote that the main realization for her at this point was that there is ‘neither Ox nor man’, meaning, she had begun to see through the subject-object division. She then added—with a vehemence that reflects earlier, not yet ripened stages of awakening—that ‘all koans are now like useless furniture to me’, that there ‘are no sentient beings to save’, and that if the Roshi spoke to her in a way that she deemed lacking, she would not hesitate to say so.

The Roshi’s comments on this are interesting, and clearly skilful. He voices encouragement and caution at the same time, always a fine balancing act. Too much encouragement can become recklessness, while too much caution can overlook the rarity of what is happening. Roshi Harada exulted at Yaeko’s breakthroughs, while the same time stressing that she was in the early stages of awakening.

Yaeko reported that her own consciousness was the same as her master’s—‘my mind’s eye is absolutely identical with yours’.18 That is always a key hallmark of awakening, the recognition that there is only One Consciousness, like one infinite ocean running through infinite rivers and tributaries, just as the One Consciousness ‘runs’ through infinite personalities. That she combines these radical proclamations with statements about her overflowing joy and gratitude for her teacher marks them as powerful and legitimate.

Yaeko at that point was somewhat limited by her view that only the Roshi could possibly understand her. This was likely a reflection of the simple fact that he had been her only teacher, and she had spent most of her time in solitary practice. She wrote, ‘You alone can understand my mind,’ but immediately followed this with ‘yet there is neither you nor me’. At this point, she had a clear view of non-duality, but years of maturing this view lay ahead of her (under normal circumstances). That she in fact only had a few days more to live makes her subsequent realizations poignant and remarkable.

The very next day, on December 26, Yaeko wrote to the Roshi expressing ‘remorse and shame’ for her previous vehemence. The Roshi counters with a reassuring comment that most early awakenings are accompanied by joyful intensity. Yaeko continues with a self-assessment that sounds remarkably more mature, all the more so given that it comes only a day after her previous outbursts of ecstasy. She writes that now that she has had a taste of awakening, she will continue to persist in her practice ‘forever’, all the while working to ‘perfect’ her personality so that she can truly integrate her understanding with embodied life.

The Roshi’s comments at this point clearly reflect his affection for the girl, as she single-mindedly strives to open her mind’s eye to the deepest levels of Reality. He remarks that he can ‘die happily’ knowing that he finally found a disciple such as Yaeko, and that he is ‘overcome by tears’ at the power of her sincerity and earnestness.

Later the same day (December 26), Yaeko writes that she has now attained the ‘last level’ of realization possible while still a disciple.19 The hallmark of this new realization is, for her, the understanding that at the ultimate level enlightenment is ‘not special’, simply because it is intrinsic to our nature. In seeing this, she also understands that heights of joyful ecstasy express a more immature state, one that she has now passed through, reaching a calmer and more stable condition. The Roshi, pleased, comments on her rarity—‘are there even a handful today who understand all this?’20—and acknowledges that she has reached the fifth stage (‘Taming the Bull’). He confirms that it indeed marks the completion of work with a teacher; that after this level the seeker is now truly on their own, guided by the light of their own passion and commitment to practice.

The next day, December 27, Yaeko reports that she has now moved deeper, and sees that ‘Buddha is none other than Mind’. (‘Mind’ in this context, refers to Universal Intelligence, or Pure Consciousness, or the Totality of All That Is). She has now broken fully through the central illusion of ‘me’ and ‘you’ (duality). The Roshi, however, comments that while this is true, her journey is not yet complete, as ‘delusive feelings’ yet remain to be ‘rooted out’. This is a key point, one that arises commonly in intensive spiritual practice. A deep awakening is often accompanied by a profound confidence. This confidence can in turn be used to face further into the unconscious mind (when feelings arise) in order to integrate remaining ‘unfinished business’.

Yaeko’s entire process at this point was highly compressed; her body would be dead within a few days. She was undergoing in less than a week what the usual seeker might undergo over years, even decades. Later on December 27 she wrote twice more, each time reporting further deepening of insight and understanding, finally ending in a direct and radical realization that her true nature was One with Buddha-mind. To this, she added an important aside: ‘…I have rid myself of the smell of enlightenment’.21

Roshi Harada was, however, no pushover of a teacher. In his comments he does not let her off the hook, noting that she was still ‘emitting the awful smell’ of enlightenment, because she was still expressing ‘self-satisfaction’ with her state of being. In other words, she had not yet entirely rooted out pride; in particular, the subtle view that her awakened state of mind was something ‘special’ that made her different. This may sound paradoxical, as the essence of her realization is that she is One with everything, but the ego is very tricky and remarkably adept at surviving even in the face of the most radical awakenings. It is here where skilled guidance from a strong teacher is vitally important.

Yaeko concludes her letters to her master showing yet more ripening of understanding, remarking, ‘I am astonished that I am that One’ (universal Consciousness). Sadly, she never had the time to integrate her Self-realization with bodily life. The very next day, December 28, she had a strong premonition of her death, and beseeched the Roshi to travel to her bedside. He did, and was with her when she passed away, confirming shortly before that ‘her Mind’s eye’ had indeed ‘opened’. He later remarked that she would have needed at least another seven or eight years to fully embody her enlightenment and purify remaining character weaknesses. (This is somewhat standard; interestingly, many wisdom traditions remark on a period of time, often lasting around seven years after an initial deep awakening, needed for purification and integration).

In his

concluding remarks Roshi Harada lamented her passing, commending her spirit as

a rare example of a householder, mortally ill and bedridden, who still managed

to penetrate deeply into her essential nature. The word ‘inspiring’ is terribly

cliché in the literature of Self-realization, but in Yaeko’s case it applies as

well as any. She gives off a terrific sense of passion and a deep and powerful

yearning to truly know. There can be

no greater motivating forces. She is a remarkable demonstration of the

possibility of profound awakening for anyone, even in the midst of the

seemingly forbidding circumstance of a debilitating physical condition. If

Yaeko, so handicapped, could achieve such breakthroughs, what holds us

back?

____________________________________

Notes

1. For my account of Socrates, I rely mainly on Luis E. Navia, Socrates: A Life Examined (Prometheus Books, 2007); and Plato, The Last Days of Socrates (London: Penguin Classics, 2003).

2. The source material for any wishing to research the ‘tripartite Christ’ (historical Jesus, Christ of dogma, and the mystical Christ) is, of course, vast. For this chapter, I drew from the following: Robert Funk, Honest to Jesus: Jesus for a new Millennium (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1996); Uta Ranke-Heinemann, Putting Away Childish Things: The Virgin Birth, the Empty Tomb, and Other Fairy Tales You Don’t Need to Believe to Have a Living Faith (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1994); Burton Mack, Who Wrote the New Testament? The Making of the Christian Myth (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1995); Ian Wilson, Jesus: The Evidence (London: Orion Publishing Group, 1998); Vivian Green, A New History of Christianity (Continuum, 2000); Andrew Harvey, Son Of Man: The Mystical Path to Christ (New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam, 1998); and the works of Bishop John Shelby Spong.

3. A Course In Miracles (Glen Ellen: Foundation for Inner Peace, 1992).

4. For this chapter my main sources are Thomas Laird, The Story of Tibet: Conversations with the Dalai Lama (New York: Grove Press, 2006), pp 82-90; and www.kagyu-asia.com/l_mila_life1.html (accessed September 22, 2010). Selections from Milarepa’s poetry are from The Hundred Thousand Songs of Milarepa, translated and edited by Garma C.C. Chang (Bolder: Shambhala Publications, 1977).

5. For my account here I rely mostly on Wild Ivy: The Spiritual Biography of Zen Master Hakuin, translated with Introduction by Norman Waddell (Boston: Shambhala Publications, 1999); and Hakuin on Kensho: The Four Ways of Knowing, edited with commentary by Albert Low (Boston: Shambhala Publications, 2006).

6. Waddell, Wild Ivy, p. 1.

7. Ibid., p. 1.

8. For my account of Ramana’s life, I rely mainly on Arthur Osborne: Ramana Maharshi and the Path of Self-Knowledge (Boston: Red Wheel/Weiser, 1970).

9. For this chapter I rely mostly on Nisargadatta’s famous work I Am That (first published in Bombay by Chetana, 1973; most recent reprint Durham: Acorn Press, 1996), as well as several works by Ramesh Balsekar.

10. I Am That: Talks with Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj (Durham: The Acorn Press, 1996), p. 354.

11. For

this chapter, I am, of course, entirely indebted to Roshi Kapleau’s classic

work The Three Pillars of Zen: Teaching,

Practice, Enlightenment (Anchor Books, revised edition 1989; most recent

printing, 2000), pp. 299-324.

12. I touch on some of these issues in my earlier book, The Three Dangerous Magi: Osho, Gurdjieff, Crowley (O-Books, 2010). For an exhaustive study of the matter, see Georg Feuerstein, Holy Madness: Spirituality, Crazy-Wise Teachers, and Enlightenment (Hohm Press, 2006).

13. The Three Pillars of Zen, p. 299.

14. For an interesting, and in some ways parallel Western story, see Suzanne Segal, Collision with the Infinite: A Life Beyond the Personal Self (Blue Dove Press, 1996).

15. The Three Pillars of Zen, pp. 299-300.

16. Ibid., p. 303.

17.

Ibid., p. 304.

18. Ibid., p. 310.

19.

Ibid., p. 313.

20. Ibid., p. 315

21. Ibid., p. 319