The following is slightly amended version of Appendix III of my book The Inner Light: Self-Realization via the Western Esoteric Tradition (Axis Mundi Books, 2014).

The word 'grimoire' is Old French for 'grammar', and is a general term for 'books of magic', many of which were originally scribed in Latin (and often safeguarded by the clergy within the cloisters of old). While modern self-help books, many of which are concerned with the art of manifestation (essentially, how to realize your desires) are believed to derive from the New Thought teachings of the 19th century, the philosophy and practice of which is ultimately tracing back to such varied characters as Phineas Quimby, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and even to Franz Mesmer and his acolytes, what is less recognized is the influence of the 'old magic' grimoires, sometimes referred to as the 'books of the sorcerers'. These books were arguably the first written documents concerned with arts of manifestation -- sometimes called 'low' or 'elemental' magic in modern parlance. Although their means and methods may seem dubious to modern audiences conditioned by 20th century psychology or softer new age ideas, they remain important cultural artifacts and fascinating documents of the history behind the longing of the common person to realize their dreams and fantasies.

The word 'grimoire' is Old French for 'grammar', and is a general term for 'books of magic', many of which were originally scribed in Latin (and often safeguarded by the clergy within the cloisters of old). While modern self-help books, many of which are concerned with the art of manifestation (essentially, how to realize your desires) are believed to derive from the New Thought teachings of the 19th century, the philosophy and practice of which is ultimately tracing back to such varied characters as Phineas Quimby, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and even to Franz Mesmer and his acolytes, what is less recognized is the influence of the 'old magic' grimoires, sometimes referred to as the 'books of the sorcerers'. These books were arguably the first written documents concerned with arts of manifestation -- sometimes called 'low' or 'elemental' magic in modern parlance. Although their means and methods may seem dubious to modern audiences conditioned by 20th century psychology or softer new age ideas, they remain important cultural artifacts and fascinating documents of the history behind the longing of the common person to realize their dreams and fantasies.

The Chief Grimoires of Magic

The main sources for the following list of grimoires are A.E. Waite, The Book of Ceremonial Magic: A Complete Grimoire (New York: Citadel Press, 1970; first published in 1898); Richard Cavendish, A History of Magic (New York: Taplinger Publishing, 1977); Owen Davies, Grimoires: A History of Magic Books (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009); Joseph H. Peterson’s excellent website www.esotericarchives.com; as well as the site www.sacred-texts.com and the antiquarian books site www.wierus.com. The order of presentation below is approximately chronological, from oldest to most recent. The grimoires are listed here for more than mere historical curiosity; they are a record of a different worldview, cultural artifacts predating (or in some cases coinciding with the beginning of) the scientific worldview. In some respects they are simply primitive attempts at science, and often were reflective of depressed economic eras in which men and women were driven to all sorts of ideas and efforts to achieve some means of control over Nature and their lives (the Spanish anthropologist Julio Caro Baroja referred to the grimoires as ‘the last products of the Medieval mind’). The kind of magic associated with grimoires is usually classified by scholars as ‘folk magic’ or sometimes as ‘demonic magic’, and is sometimes considered polar opposite to the transcendent mysticism of a Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, a St. John of the Cross, or a Jacob Boehme. However that is not entirely accurate, as several of the important grimoires do in fact contain disciplined instructions for achieving deep spiritual purification and alignment prior to consorting with the so-called darker realms. (Modern psychology, especially of the Jungian sort, interprets the realm of 'lower spirits' as that of the collective unconscious and our personal tie-in to that as our 'shadow'. While a useful interpretive model, those of earlier times did not think of these spirits as projections of their psyche, but rather as ontologically real. That some systems involved controlling such spirits via the invocation of angelic power only attested to how seriously the matter was taken).

Although the grimoires below begin with the 3rd–4th century CE Sepher ha-Razim, they certainly have older roots, mainly in the Greco-Roman world of approximately 300 BCE–300 CE. Religion and magic have traditionally overlapped and at times been impossible to distinguish from each other (for example, both Christ and Moses were labeled goetes [sorcerers] by their critics, not just for polemical reasons, but because the legends associated with them were indistinguishable from those credited to magicians).1 That said, a key element of both religion and magic has been belief in the power of the spoken word, and it was this—and in particular the usage of spiritual names—that most of the magical grimoires ultimately came to be based on. The roots of the tradition of spiritual power via the usage of names or words goes back to the Babylonians, Sumerians, and ancient Egyptians. In Kabbalism the term given to the ‘Master of the Divine Name’ was Ba’al Shem, the one who reputedly had secret knowledge of the Holy Names, including the Tetragrammaton. Even Socrates was recorded (by Plato) to have claimed that the power of a particular plant to heal would only work if certain special words were uttered at the same time:

…when he asked me if I knew the cure of the headache, I answered, but with an effort, that I did know. ‘And what is it?’ he said. I replied that it was a kind of leaf, which required to be accompanied by a charm, and if a person would repeat the charm at the same time that he used the cure, he would be made whole; but that without the charm the leaf would be of no avail.2

This usage of ‘words of power’ had several faces. The highest usages were for the alignment of one’s soul with its divine source (as in the Eastern usage of the ‘mantra’), and for healing or protection, as in the original usage of ‘abracadabra’ (see below). Lower forms involved using words of power for binding and controlling demons, and perhaps lowest of all was employing particular words for curses. (The most common form of Greco-Roman curse was performed via the defixio, written down on a piece of wax or metal and placed somewhere underground. It was believed that the words had an instantaneous effect.3 Doubtless in part because of the power of suggestion, many of these curses had results—most obviously if the target was made aware that they had been cursed!). In general, however, the magical grimoires and the practitioners who used them were less concerned with affecting others than they were with advancing their own cause, either materially, or in more rare and elevated cases, by contacting higher (angelic) guidance and furthering their spiritual development or large scale ambitions (the 16th century scholar-magician John Dee, and his efforts with his controversial seer and alchemist Edward Kelley, being a good example).

There were more grimoires of note than the eighteen listed below, but what follows are generally recognized as some of the most influential ones.

1. Sepher ha-Razim: This work of Jewish magic is one of the oldest magical texts, generally dated to the 3rd or 4th century CE, thus predating major Kabbalistic works such as the Zohar and the Bahir. The book contains many of the essential elements of the grimoires that followed, including shamanistic practices such as healing, attacks on enemies, obtaining prophetic visions, and so forth, as well as the somewhat peculiar marriage of these rituals to the invocation of the Hebrew holy names of God. As with the Book of Raziel (see below) according to legend this book was conveyed by the archangel Raziel, in this case to Noah.

2. Ghayat al-Hakim (The Aim of the Sage): Originally written in Arabic (in Spain) somewhere between the years 1000 and 1150 CE, this famed grimoire was translated into Spanish around 1250, and shortly thereafter into Latin, after which it came to be known as The Picatrix. Deriving mostly from older Greek and Persian traditions, it was essentially a manual of astrological and ‘astral’ magic, including instructions for ‘drawing down’ the powers and energies of the stars and planets into talismanic symbols. It did not deal with demonology per se, but because some of its rituals involved animal sacrifices (doves and goats) it was denounced as a work of necromancy.

2. Ghayat al-Hakim (The Aim of the Sage): Originally written in Arabic (in Spain) somewhere between the years 1000 and 1150 CE, this famed grimoire was translated into Spanish around 1250, and shortly thereafter into Latin, after which it came to be known as The Picatrix. Deriving mostly from older Greek and Persian traditions, it was essentially a manual of astrological and ‘astral’ magic, including instructions for ‘drawing down’ the powers and energies of the stars and planets into talismanic symbols. It did not deal with demonology per se, but because some of its rituals involved animal sacrifices (doves and goats) it was denounced as a work of necromancy.

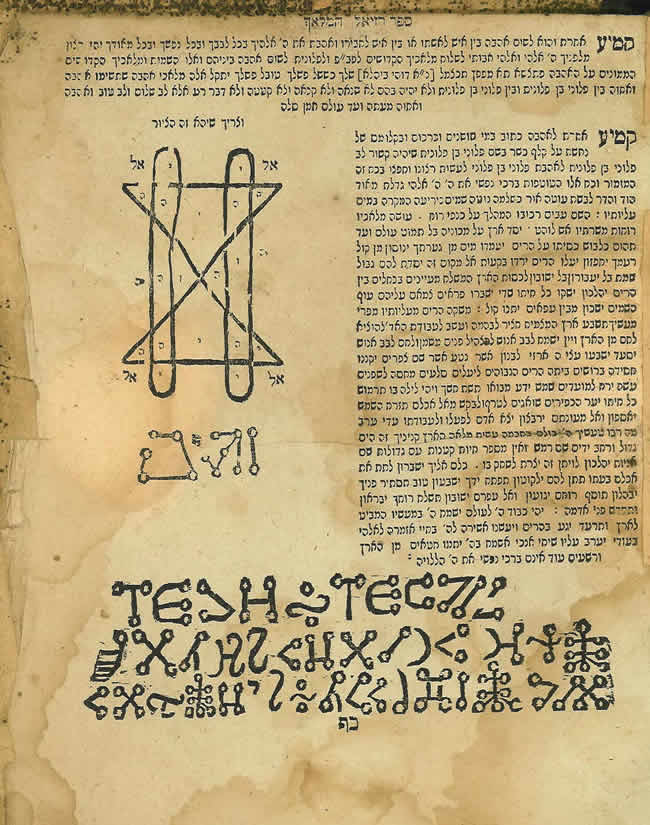

3. Sepher Raziel HaMalakh (The Book of Raziel the Archangel): An important medieval Jewish grimoire, probably written in the 13th century, and one of the foundational sources of some of the major grimoires to follow. This book—not to be confused with the 16th century grimoire called Sepher Raziel that was written by a Christian and based on standard Solomonic magic—had an influence on both Trithemius and Agrippa (see below), arguably the two most important Renaissance magi. According to the legend Raziel was an archangel who transmitted certain ‘secret’ teachings to Adam and Eve, after their expulsion from Eden, so they could return to their divine condition. (The name ‘Raziel’ itself means ‘secrets of God’).

Raziel had done this without permission and as such was considered a rebel by his fellow angels, and his book duly confiscated. (According to some legends it was later retrieved by God, however, and eventually found its way via Archangel Raphael to Noah, who used its information to build the ark). Raziel is the Jewish parallel of Prometheus, the Greek god who ‘stole fire from heaven’ to give to humans, in so doing incurring the wrath of Zeus. These myths lie behind the notorious and glamorous reputation of high magic, the idea that the individual can determine their own spiritual fate by independent acts of will (with all the Faustian perils included), though a deeper understanding of magic transcends these stereotypes.

Raziel had done this without permission and as such was considered a rebel by his fellow angels, and his book duly confiscated. (According to some legends it was later retrieved by God, however, and eventually found its way via Archangel Raphael to Noah, who used its information to build the ark). Raziel is the Jewish parallel of Prometheus, the Greek god who ‘stole fire from heaven’ to give to humans, in so doing incurring the wrath of Zeus. These myths lie behind the notorious and glamorous reputation of high magic, the idea that the individual can determine their own spiritual fate by independent acts of will (with all the Faustian perils included), though a deeper understanding of magic transcends these stereotypes.

4. Liber Juratus Honorii (Sworn Book of Honorius): This book, allegedly a compendium by a group of magicians attempting to save their teachings from being lost to the flames of Catholic book-burners, is recognized as one of the oldest medieval grimoires, probably written sometime during the 13th or early 14th century. Many magic grimoires acquired notorious reputations, but this one more than most, owing in part to its apparent ‘Trojan Horse’ method of transmitting its teachings on the means of controlling and using demons for personal gain. It did this by claiming that its practical demonology was sanctioned by the Church, proclaiming in an opening spiel, ‘…I give unto thee the Keys of the Kingdom of Heaven, and unto thee alone the power of commanding the Prince of Darkness and his angels…’ (Subsequent Church authorities would use this spurious Church authorization as proof of the trickery of demons).

The attribution of authorship to ‘Honorius’ has been speculated to apply to a semi-mythical medieval ‘Honorius of Thebes’ (mentioned also by Trithemius and Agrippa), a type of spokesperson for a secret group of magicians who later become conflated with the identity of a pope, either Honorius III (1148–1227), or even to the ‘Dark Ages’ Pope Honorius I (d. 638). The Sworn Book of Honorius, based on a conversation with an archangel named Hochmel (after the sephira Chokmah) and a sizeable ninety-three chapters long, is a key and influential grimoire, containing many of the basic elements of practical ‘goetic’ magic that were to appear in a host of grimoires to follow, the more important of which are listed below. Perhaps more significantly this grimoire touches on the whole area of the question of the usage of magic and sorcery within the Church, and even beyond that, to the essential questions about magic vs. divinity, including the nature of Christ and whether or not he was a magician himself (as discussed in Chapter 4).

The attribution of authorship to ‘Honorius’ has been speculated to apply to a semi-mythical medieval ‘Honorius of Thebes’ (mentioned also by Trithemius and Agrippa), a type of spokesperson for a secret group of magicians who later become conflated with the identity of a pope, either Honorius III (1148–1227), or even to the ‘Dark Ages’ Pope Honorius I (d. 638). The Sworn Book of Honorius, based on a conversation with an archangel named Hochmel (after the sephira Chokmah) and a sizeable ninety-three chapters long, is a key and influential grimoire, containing many of the basic elements of practical ‘goetic’ magic that were to appear in a host of grimoires to follow, the more important of which are listed below. Perhaps more significantly this grimoire touches on the whole area of the question of the usage of magic and sorcery within the Church, and even beyond that, to the essential questions about magic vs. divinity, including the nature of Christ and whether or not he was a magician himself (as discussed in Chapter 4).

5. Clavicula Salomonis (The Key of Solomon): The oldest extant manuscript of this famous grimoire seems to be the Magic Treatise of Solomon, originally written in Greek in 1572, although Waite and others speculated that the first version of the work was written sometime between 1350 and 1450. Undoubtedly it had its inspiration in apocryphal texts written over a thousand years earlier, such as The Revelation of Adam and Testament of Solomon. That said, no singular original version of the Clavicula is recognized by scholars, although the work itself was highly influential in the grimoire world and led to many derivative versions. The attribution to Solomon is of course spurious, and the book is not of a Jewish teaching or origin, despite its usage of Hebrew terms (the Hebrew translation of it only appeared in the 17th century; the earliest copies are in Greek). The essential feature of the demonological grimoire lay at the basis of this book, that being the command and control of lower spirits and structured manifestation practices (based on the cooperation of these spirits) allegedly leading to the fulfilment of personal wishes. A key element of the Clavicula is its religiously pious tone, and its insistence that the operator must invoke the presence of God (via the Hebrew Holy Names) and be ceremonially purged of ‘self-recognized sin’ (via confession). This focus on spiritual and psychological purification, prior to evoking the spirits, was to be even more strongly echoed in the grimoire of Abramelin.

5. Clavicula Salomonis (The Key of Solomon): The oldest extant manuscript of this famous grimoire seems to be the Magic Treatise of Solomon, originally written in Greek in 1572, although Waite and others speculated that the first version of the work was written sometime between 1350 and 1450. Undoubtedly it had its inspiration in apocryphal texts written over a thousand years earlier, such as The Revelation of Adam and Testament of Solomon. That said, no singular original version of the Clavicula is recognized by scholars, although the work itself was highly influential in the grimoire world and led to many derivative versions. The attribution to Solomon is of course spurious, and the book is not of a Jewish teaching or origin, despite its usage of Hebrew terms (the Hebrew translation of it only appeared in the 17th century; the earliest copies are in Greek). The essential feature of the demonological grimoire lay at the basis of this book, that being the command and control of lower spirits and structured manifestation practices (based on the cooperation of these spirits) allegedly leading to the fulfilment of personal wishes. A key element of the Clavicula is its religiously pious tone, and its insistence that the operator must invoke the presence of God (via the Hebrew Holy Names) and be ceremonially purged of ‘self-recognized sin’ (via confession). This focus on spiritual and psychological purification, prior to evoking the spirits, was to be even more strongly echoed in the grimoire of Abramelin.

6. The Book of the Sacred Magic of Abramelin the Mage: This book, supposedly written by one Abraham ben Simon (c. 1362-c. 1458), a Jewish writer from Worms (located in modern-day western Germany), features the story of Abraham traveling to Egypt where he allegedly encounters an Egyptian magician named Abramelin, and records the magician’s teachings to his son Lamech. The book is internally dated to 1458, although there is some evidence that it may have been written a century earlier. The earliest extant version of the book in manuscript form is in German and was written down in 1608. The grimoire was made popular via S.L. Mathers’ copy taken from a flawed version in a French library and first published in English in 1898. Subsequent research has established that older, more accurate versions were found in Germany (including such notable facts that the six-month retreat originally reported by Mathers, based on Abramelin’s guidance, was in fact eighteen months).4 Despite the apparent Kabbalistic tone of the book, some, including the Kabbalah scholar Gershom Scholem, believed that the author, Abraham of Worms, was ‘not in fact a Jew’, and that the German original was ‘badly translated’ into Hebrew, not from Hebrew. Scholem further claimed that the book showed a ‘partial influence of Jewish ideas’ but did not have ‘any strict parallel in Kabbalistic literature’.5 The essential basis of the Abramelin grimoire is the initial purification procedure (involving daily prayer and other austerities for a year and a half), followed by the direct experience of the ‘Holy Guardian Angel’, a title whose origin appears to lie with this grimoire, although there is evidence that Zoroastrians long before used a similar term. The Holy Guardian Angel is, essentially, the rarefied and awakened part of our nature (often called the ‘true self’).

6. The Book of the Sacred Magic of Abramelin the Mage: This book, supposedly written by one Abraham ben Simon (c. 1362-c. 1458), a Jewish writer from Worms (located in modern-day western Germany), features the story of Abraham traveling to Egypt where he allegedly encounters an Egyptian magician named Abramelin, and records the magician’s teachings to his son Lamech. The book is internally dated to 1458, although there is some evidence that it may have been written a century earlier. The earliest extant version of the book in manuscript form is in German and was written down in 1608. The grimoire was made popular via S.L. Mathers’ copy taken from a flawed version in a French library and first published in English in 1898. Subsequent research has established that older, more accurate versions were found in Germany (including such notable facts that the six-month retreat originally reported by Mathers, based on Abramelin’s guidance, was in fact eighteen months).4 Despite the apparent Kabbalistic tone of the book, some, including the Kabbalah scholar Gershom Scholem, believed that the author, Abraham of Worms, was ‘not in fact a Jew’, and that the German original was ‘badly translated’ into Hebrew, not from Hebrew. Scholem further claimed that the book showed a ‘partial influence of Jewish ideas’ but did not have ‘any strict parallel in Kabbalistic literature’.5 The essential basis of the Abramelin grimoire is the initial purification procedure (involving daily prayer and other austerities for a year and a half), followed by the direct experience of the ‘Holy Guardian Angel’, a title whose origin appears to lie with this grimoire, although there is evidence that Zoroastrians long before used a similar term. The Holy Guardian Angel is, essentially, the rarefied and awakened part of our nature (often called the ‘true self’).

The Abramelin grimoire is exceptional in its highly disciplined focus and insistence on the awakening of this higher spiritual principle and faculty, prior to working with lower orders of spirits. It has often been considered to be the grimoire par excellence of high magic, as opposed to the majority of grimoires which are concerned more with ‘low magic’ (the art of practical manifestation), and less with the structured practices of inner discipline needed to align with the higher nature of the soul. In this regard, the Abramelin grimoire is as much a teaching of mysticism as it is of magic. Ultimately however its concern is also practical, and its cosmology is consistent with Hermetic and Kabbalistic magical worldviews in which angels are thought to control demons who in turn control much of the world. Abramelin guides candidates into becoming ‘Masters of Light’ who, utilizing their ascetic training, can then control demonic forces with the aid of specific ‘magic squares’ specified and illustrated in the book. These allegedly allow for the magician to gain remarkable powers enabling him to obtain wealth, love, the ability to heal diseases or transform into an animal, and even to raise the dead. Some of the magic squares found in the book have been traced to the times of Charlemagne (via 8th century CE Carolingian bibles) and further back to 2nd century CE Roman villas in England.6

The Abramelin grimoire is exceptional in its highly disciplined focus and insistence on the awakening of this higher spiritual principle and faculty, prior to working with lower orders of spirits. It has often been considered to be the grimoire par excellence of high magic, as opposed to the majority of grimoires which are concerned more with ‘low magic’ (the art of practical manifestation), and less with the structured practices of inner discipline needed to align with the higher nature of the soul. In this regard, the Abramelin grimoire is as much a teaching of mysticism as it is of magic. Ultimately however its concern is also practical, and its cosmology is consistent with Hermetic and Kabbalistic magical worldviews in which angels are thought to control demons who in turn control much of the world. Abramelin guides candidates into becoming ‘Masters of Light’ who, utilizing their ascetic training, can then control demonic forces with the aid of specific ‘magic squares’ specified and illustrated in the book. These allegedly allow for the magician to gain remarkable powers enabling him to obtain wealth, love, the ability to heal diseases or transform into an animal, and even to raise the dead. Some of the magic squares found in the book have been traced to the times of Charlemagne (via 8th century CE Carolingian bibles) and further back to 2nd century CE Roman villas in England.6

7. Le Grand Albert: This text first appeared in a Latin edition in 1493. It was mainly concerned with ‘natural magic’, including the usage of herbs, precious stones, ways to ward off diseases, usages of alchemy and physiognomy, and so forth. ‘Albert’ supposedly referred to Albertus Magnus (1200?-1280), the Catholic bishop who was learned in science, theology, and allegedly in certain occult arts, including astrology and alchemy. Almost certainly it was not written by Albertus himself, despite the fact that some of his material was probably reproduced in the text. Later editions of this work became popular in 18th century France in particular.

8. The Heptameron: This work first appeared in 1496 and was attributed to the Italian philosopher and astrologer Peter d’Abano (1250–1316), but as with so many grimoires, this is generally recognized as another false attribution. This grimoire later appeared as an appendix in works attributed to Agrippa in the 16th century. It is in the tradition of medieval and Renaissance grimoires, being a manual of ritual and practical astrological magic.7

9. The Steganographia: This work was written by the important German abbot, cryptographer, and magus Johannes Trithemius (1462–1516) in 1499. It was widely distributed in manuscript form for many years but not printed until 1606. The fact that Trithemius was an abbot of a monastery and also was delving into the arcane arts was not exceptional, owing mostly to the fact that many Hermetic texts brought to light by Marcilio Ficino (1433–1499) via his Florentine Academy, though attributed to Hermes Trismegistus, were usually put together by Hellenistic Christians in the early centuries immediately after Christ and were thus not—at least initially—considered particularly troublesome for the Church.8 The Steganographia was, however, placed on the list of books prohibited by the Catholic Church in 1609, three years after its publication. It was initially believed to be essentially a work of angel magic, utilizing codes in order to communicate with spirits and people in non-ordinary fashions. Over time however the book has been revealed to be mostly a form of cryptography, utilizing the ‘magic work’ as an elaborate cover, although Trithemius was, without question, concerned with occult sciences (he was, after all, one of Agrippa’s chief mentors, and John Dee, himself deeply involved with angel magic, made a study of his work).

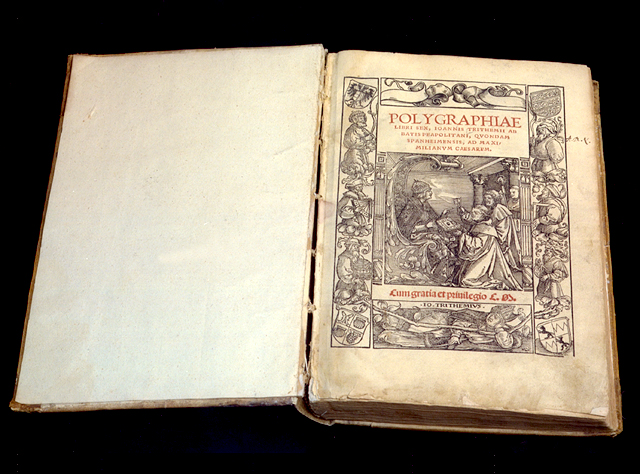

Trithemius’s last and posthumously published work, Polygraphiae (1518), is generally considered the first book on cryptology, the science of encoding and decoding messages. Many of Trithemius’s ideas, especially those involving celestial, angelic, and natural magic, shaped in part by Albertus Magnus, Ficino, and Pico della Mirandola, were key influences on Agrippa.

Trithemius’s last and posthumously published work, Polygraphiae (1518), is generally considered the first book on cryptology, the science of encoding and decoding messages. Many of Trithemius’s ideas, especially those involving celestial, angelic, and natural magic, shaped in part by Albertus Magnus, Ficino, and Pico della Mirandola, were key influences on Agrippa.

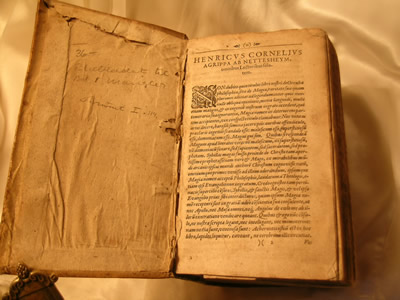

10. De Occulta Philosophia (On Occult Philosophy): This work, a massive encyclopedia of magical lore written in 1510 by Agrippa, is probably the single most influential text ever composed on the arts of high and low magic. It was not published until 1533, apparently at the suggestion of Trithemius, who was one of Agrippa’s main mentors. It was translated into English in 1651 as Three Books of Occult Philosophy.

An excellent edition of the book was put out by Llewellyn, exhaustively edited and annotated by Donald Tyson, in 1993. Agrippa himself was a somewhat ambiguous figure; he wrote his work in his early 20s, but there are reports that near the end of his life he had condemned his own writings. (This was not uncommon among Renaissance-era mages, however, as they often had to maneuver carefully through the thickets of ecclesiastical intolerance).9

An excellent edition of the book was put out by Llewellyn, exhaustively edited and annotated by Donald Tyson, in 1993. Agrippa himself was a somewhat ambiguous figure; he wrote his work in his early 20s, but there are reports that near the end of his life he had condemned his own writings. (This was not uncommon among Renaissance-era mages, however, as they often had to maneuver carefully through the thickets of ecclesiastical intolerance).9

11. Fourth Book of Occult Philosophy: This is the notoriously disputed ‘follow up’ book to Agrippa’s enormously influential De Occulta Philosophia. The Fourth Book was published in 1559 (over twenty years after Agrippa had died), and first translated into English in 1665. It was primarily concerned with practical magic (in contrast to Agrippa’s Three Books which was largely theoretical), including the summoning of demons. Agrippa’s alleged student Johann Weyer (see the following entry) dismissed the Fourth Book as pseudepigraphical, believing that it was beneath the quality of his teacher. Despite his protests the book became popular and was widely distributed among 16th and 17th century occultists, including John Dee, who carried around a copy with him during his sojourns on the Continent and his meetings with Emperor Rudolph and famed alchemists such as Michael Meier in Bohemia in the 1580s.

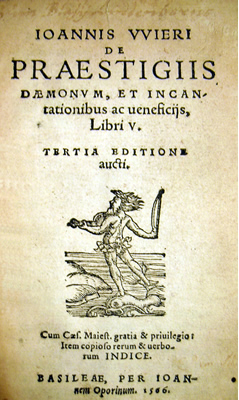

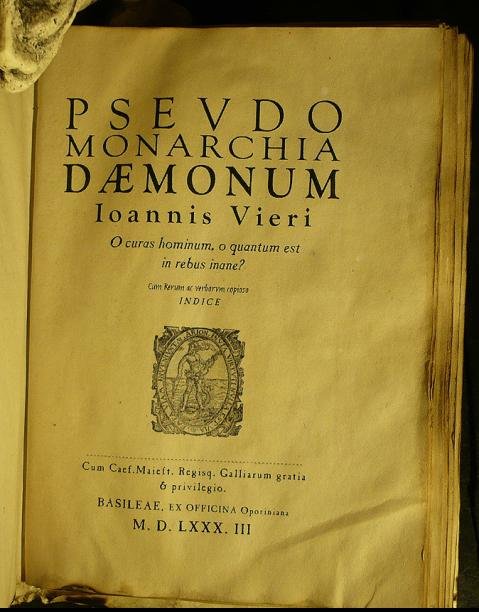

12. De Praestigiis Daemonum (On the Deceptions of Demons): This is not a grimoire per se, but rather a skeptical study of them that warrants mention here for its influence. Originally published by the Dutch proto-psychiatrist, physician, and demonologist Johann Weyer in 1563, it was a rebuttal of Kramer and Sprenger’s 1486 witch-hunter’s manual Malleus Maleficarum. Weyer’s book also included a section on ‘spells and poisons’, reflecting the view that darker forms of sorcery were often thought to be associated with assassins and their art. In his 1577 edition of the book Weyer included an influential appendix called Pseudomonarchia Daemonum (False Kingdom of Demons), in which he listed sixty-nine demons (minus images of them or the sigils they were later associated with). This list (with the order mixed up), along with three other demons, re-appeared sometime later to comprise the seventy-two demons of the Goetia (see below). Weyer’s source for the demonic hierarchy was a book called Liber Officiorum Spirituum (The Book of the Offices of Spirits), a copy of which was owned by Trithemius, who himself had taught both the famed alchemist Paracelsus as well as Cornelius Agrippa, the latter of whom was supposedly the teacher of Weyer. At any rate, the list of demons specified and popularized by the Goetia and Dictionnaire Infernal appear to derive from at least as far back as 1500, and probably much further. As for Weyer, his intentions in publishing his book were not always understood. Although he has been nominated as the founder of modern psychiatry (see Chapter 5), in part for his brave efforts to counter the barbaric witch-trials via his view that most ‘witches’ were innocent women suffering from mental illness, he did not doubt the reality and power of Satan or of his demons, and believed magicians to be deserving of prosecution and severe punishment.

12. De Praestigiis Daemonum (On the Deceptions of Demons): This is not a grimoire per se, but rather a skeptical study of them that warrants mention here for its influence. Originally published by the Dutch proto-psychiatrist, physician, and demonologist Johann Weyer in 1563, it was a rebuttal of Kramer and Sprenger’s 1486 witch-hunter’s manual Malleus Maleficarum. Weyer’s book also included a section on ‘spells and poisons’, reflecting the view that darker forms of sorcery were often thought to be associated with assassins and their art. In his 1577 edition of the book Weyer included an influential appendix called Pseudomonarchia Daemonum (False Kingdom of Demons), in which he listed sixty-nine demons (minus images of them or the sigils they were later associated with). This list (with the order mixed up), along with three other demons, re-appeared sometime later to comprise the seventy-two demons of the Goetia (see below). Weyer’s source for the demonic hierarchy was a book called Liber Officiorum Spirituum (The Book of the Offices of Spirits), a copy of which was owned by Trithemius, who himself had taught both the famed alchemist Paracelsus as well as Cornelius Agrippa, the latter of whom was supposedly the teacher of Weyer. At any rate, the list of demons specified and popularized by the Goetia and Dictionnaire Infernal appear to derive from at least as far back as 1500, and probably much further. As for Weyer, his intentions in publishing his book were not always understood. Although he has been nominated as the founder of modern psychiatry (see Chapter 5), in part for his brave efforts to counter the barbaric witch-trials via his view that most ‘witches’ were innocent women suffering from mental illness, he did not doubt the reality and power of Satan or of his demons, and believed magicians to be deserving of prosecution and severe punishment.

The efforts of Weyer were countered by authors such as Jean Bodin, whose On the Demon-Mania of Witches (1580) sought to maintain the orthodox view that witches were both real and complicit tools of Satan. Weyer’s work was adapted by Reginald Scot in his Discovery of Witchcraft (1584). Scot used Weyer’s work to argue further against the unjust treatment of witches, based on the essential point that they did not actually exist (as conceived of by the Church) and that all so-called ‘magic acts’ could be explained by arts of illusion and trickery. His book is often considered the first text on ‘stage magic’ (‘legerdemain’, or sleight of hand). King James I (1566–1625), a demonologist himself, added to the furor around the attempts of Scot and Weyer to demystify the so-called maleficia of witches, by ordering all copies of Scot’s work burnt upon his accession to the English throne in 1603.

The efforts of Weyer were countered by authors such as Jean Bodin, whose On the Demon-Mania of Witches (1580) sought to maintain the orthodox view that witches were both real and complicit tools of Satan. Weyer’s work was adapted by Reginald Scot in his Discovery of Witchcraft (1584). Scot used Weyer’s work to argue further against the unjust treatment of witches, based on the essential point that they did not actually exist (as conceived of by the Church) and that all so-called ‘magic acts’ could be explained by arts of illusion and trickery. His book is often considered the first text on ‘stage magic’ (‘legerdemain’, or sleight of hand). King James I (1566–1625), a demonologist himself, added to the furor around the attempts of Scot and Weyer to demystify the so-called maleficia of witches, by ordering all copies of Scot’s work burnt upon his accession to the English throne in 1603.

13. Clavicula Salomonis Regis (The Lesser Key of Solomon, or, The Goetia): The author of this famed demonology grimoire is unknown. The work, in a partly complete form, was mentioned by Reginald Scot in 1584, and exists in manuscript form in the British Museum in several editions dating to the mid-to-late 1600s, based in part on Weyer’s Pseudomonarchia Daemonum, The Steganographia of Trithemius, earlier grimoires from the 14th century (including the Sworn Book of Honorius), and possibly material from much older Gnostic texts. The work has also been known as the Lemegeton, and more informally as The Goetia, although this latter word (Greek for ‘sorcery’) actually refers to only the first part of the book. In all the Lemegeton contains five books (some versions contain only four, omitting the last book, Ars Notoria): Ars Goetia (The Art of Sorcery); Ars Theurgia Goetia (The Art of High Magic and Sorcery); Ars Paulina (The Art of Paul), which is a reference to the apostle Paul; Ars Almadel (The Art of the Almadel), the ‘almadel’ being a wax tablet used for rituals; and Ars Notoria (The Notable Art), essentially a section of prayers deriving from much older texts. Although the notoriety of the Lemegeton is based on its representation of seventy-two demons and the means by which to contact and control them, it is not just a manual of sorcery, including as it does theurgical and religious practices. The seventy-two demons are thought by some to originate with the Kabbalistic idea of the Shemhamphorasch (the ‘explicit’ or ‘interpreted’ name, a reference to the Tetragrammaton), connected to Exodus 14:19–21, in which are found three verses each of seventy-two letters. It is believed by some Kabbalists that when organized in a specific manner the letters reveal the names of seventy-two angels (or Names of God), and that further, if the symbolic sigils of these angels are reversed, the names of the seventy-two demons emerge.

13. Clavicula Salomonis Regis (The Lesser Key of Solomon, or, The Goetia): The author of this famed demonology grimoire is unknown. The work, in a partly complete form, was mentioned by Reginald Scot in 1584, and exists in manuscript form in the British Museum in several editions dating to the mid-to-late 1600s, based in part on Weyer’s Pseudomonarchia Daemonum, The Steganographia of Trithemius, earlier grimoires from the 14th century (including the Sworn Book of Honorius), and possibly material from much older Gnostic texts. The work has also been known as the Lemegeton, and more informally as The Goetia, although this latter word (Greek for ‘sorcery’) actually refers to only the first part of the book. In all the Lemegeton contains five books (some versions contain only four, omitting the last book, Ars Notoria): Ars Goetia (The Art of Sorcery); Ars Theurgia Goetia (The Art of High Magic and Sorcery); Ars Paulina (The Art of Paul), which is a reference to the apostle Paul; Ars Almadel (The Art of the Almadel), the ‘almadel’ being a wax tablet used for rituals; and Ars Notoria (The Notable Art), essentially a section of prayers deriving from much older texts. Although the notoriety of the Lemegeton is based on its representation of seventy-two demons and the means by which to contact and control them, it is not just a manual of sorcery, including as it does theurgical and religious practices. The seventy-two demons are thought by some to originate with the Kabbalistic idea of the Shemhamphorasch (the ‘explicit’ or ‘interpreted’ name, a reference to the Tetragrammaton), connected to Exodus 14:19–21, in which are found three verses each of seventy-two letters. It is believed by some Kabbalists that when organized in a specific manner the letters reveal the names of seventy-two angels (or Names of God), and that further, if the symbolic sigils of these angels are reversed, the names of the seventy-two demons emerge.

14. Le Petit Albert: The ‘little brother’ of Le Grand Albert, this popular grimoire seems to have first appeared in France around 1668, with numerous reprintings over the next century. ‘Albert’ in this case apparently refers not to Albertus Magnus, but to a certain Albertus Parvus Lucius. Le Petit Albert was, as with Barrett’s The Magus (see below), a composite of numerous previous writings, including possibly those of Paracelsus. This book was condemned and censored by the Catholic Church, which allegedly made its value on the 18th–19th century French ‘black market’ skyrocket. The book achieved a remarkable popularity in rural France, was at times compared to a type of ‘farmer’s almanac’, was devoid of demonic conjurations, and was more concerned with the practical element of ‘low magic’ so as to cause desired changes in one’s life. Perhaps its more infamous recipe concerned that of the so-called ‘Hand of Glory’, based on a type of necromancy that involved procuring the left hand of an executed man. This object could then allegedly confer certain powers of protection, as well as the ability to become invisible.

15. Grimorium Verum (The True Grimoire): This work was written sometime around 1750 in Italian, probably in Rome (with later French translations). Despite its lofty-sounding title, the authorship, as with so many related works, is unclear, even confusing. The book claims to have been translated from Hebrew by a certain ‘Dominican Jesuit’ called Plaingiere, and allegedly published in 1517 by an ‘Alibeck the Egyptian’. A.E. Waite pointed out that a ‘Dominican Jesuit’ is an absurdity, suggesting the grimoire was written by a ‘Jew or heretic’. The mid-to-late18th century was a time when Egyptian romanticism had gripped the European occult subculture (Court de Gebelin had first introduced his notion of the Tarot cards deriving from Egyptian mystery teachings not long after The Grimorium Verum appeared), a possible influence behind the attribution to an Egyptian publisher. The Grimorium Verum was influenced by the Clavicula Salomonis, the Lemegeton, and Weyer’s Pseudomonarchia Daemonum, and is in the usual tradition of evoking demons (many of the same ones found in the Lemegeton, including the very highest in the demonic hierarchy) for the purposes of personal gain, while at the same time emphasizing the standard Christian piety and need to invoke the heavenly hosts and the ‘Most High’ first. Nevertheless, S.L. Mathers, in his 1888 English edition of The Key of Solomon, dismissed the Grimorium Verum as ‘full of evil magic’ and warned the occult student to avoid it. (An excellent scholarly study of this grimoire was brought out by Joseph Peterson in 2007).10

15. Grimorium Verum (The True Grimoire): This work was written sometime around 1750 in Italian, probably in Rome (with later French translations). Despite its lofty-sounding title, the authorship, as with so many related works, is unclear, even confusing. The book claims to have been translated from Hebrew by a certain ‘Dominican Jesuit’ called Plaingiere, and allegedly published in 1517 by an ‘Alibeck the Egyptian’. A.E. Waite pointed out that a ‘Dominican Jesuit’ is an absurdity, suggesting the grimoire was written by a ‘Jew or heretic’. The mid-to-late18th century was a time when Egyptian romanticism had gripped the European occult subculture (Court de Gebelin had first introduced his notion of the Tarot cards deriving from Egyptian mystery teachings not long after The Grimorium Verum appeared), a possible influence behind the attribution to an Egyptian publisher. The Grimorium Verum was influenced by the Clavicula Salomonis, the Lemegeton, and Weyer’s Pseudomonarchia Daemonum, and is in the usual tradition of evoking demons (many of the same ones found in the Lemegeton, including the very highest in the demonic hierarchy) for the purposes of personal gain, while at the same time emphasizing the standard Christian piety and need to invoke the heavenly hosts and the ‘Most High’ first. Nevertheless, S.L. Mathers, in his 1888 English edition of The Key of Solomon, dismissed the Grimorium Verum as ‘full of evil magic’ and warned the occult student to avoid it. (An excellent scholarly study of this grimoire was brought out by Joseph Peterson in 2007).10

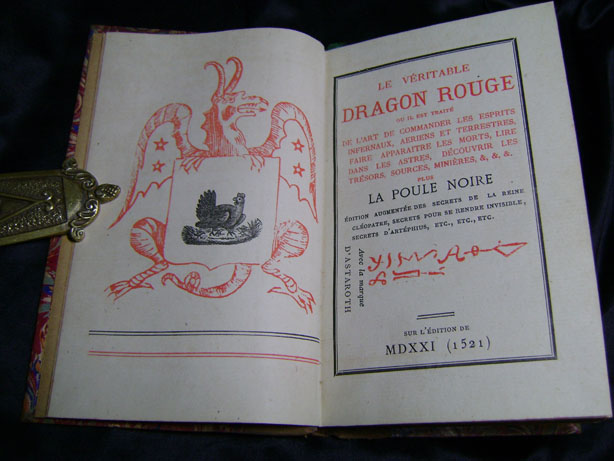

16. The Grand Grimoire: Also known (in some later editions) as Le Dragon Rouge (The Red Dragon), this notorious grimoire was written in Italian (with early French translations) sometime in the mid to late 18th century, with reprints into the 19th century. It often claims a date of 1521, but this is known to be false. The book is styled upon The Sworn Book of Honorius and The Key of Solomon, but is of a darker tone, centering on forming a Faustian pact with Lucifer (or his demonic ‘Prime Minister Lucifuge Rofocale’). The subtitle of the grimoire makes clear its purpose: ‘The art of controlling celestial, aerial, terrestrial, and infernal spirits. With the TRUE SECRET of speaking with the dead, winning whenever playing the lottery, discovering hidden treasure, etc.’ The grimoire begins with a blend of prayer to God via Hebrew holy names, ascetic austerities (though mild in comparison to Abramelin), the sacrifice of a goat (which is straight out of Leviticus), and other oddities such as procuring four nails from the coffin of a child who has recently died—a probable echo of an old belief, mentioned by Apuleius, that fingers, noses, and nails from the cross of a crucified man possess great power. (Necromancy—the practice of utilizing dead people to contact other realms—has ancient animistic roots. Keith Thomas cited the case of a 14th century magician found carrying around the decapitated head of a Saracen that he had procured in Spain, ‘within which he proposed to enclose a spirit that would answer his questions’).11 All this is followed by the construction of a magic circle and the summoning of ‘Emperor Lucifer’ to appear ‘by the name of the great living God, his dear son and the Holy Ghost and by the power of Adonai, Elohim’, etc. The book then descends into a number of rituals involving further animal sacrifice, including boiling a cat, cutting the throat of a young wolf, and decapitating a frog, elements that render it one of the baser grimoires and a true book of sorcery with roots in primitive shamanism. (Needless to say, its prime value lies in an anthropological history of ideas within cultural context, not as an instruction manual—although that said, it did in fact become a source of working material for some forms of Caribbean sorcery).

16. The Grand Grimoire: Also known (in some later editions) as Le Dragon Rouge (The Red Dragon), this notorious grimoire was written in Italian (with early French translations) sometime in the mid to late 18th century, with reprints into the 19th century. It often claims a date of 1521, but this is known to be false. The book is styled upon The Sworn Book of Honorius and The Key of Solomon, but is of a darker tone, centering on forming a Faustian pact with Lucifer (or his demonic ‘Prime Minister Lucifuge Rofocale’). The subtitle of the grimoire makes clear its purpose: ‘The art of controlling celestial, aerial, terrestrial, and infernal spirits. With the TRUE SECRET of speaking with the dead, winning whenever playing the lottery, discovering hidden treasure, etc.’ The grimoire begins with a blend of prayer to God via Hebrew holy names, ascetic austerities (though mild in comparison to Abramelin), the sacrifice of a goat (which is straight out of Leviticus), and other oddities such as procuring four nails from the coffin of a child who has recently died—a probable echo of an old belief, mentioned by Apuleius, that fingers, noses, and nails from the cross of a crucified man possess great power. (Necromancy—the practice of utilizing dead people to contact other realms—has ancient animistic roots. Keith Thomas cited the case of a 14th century magician found carrying around the decapitated head of a Saracen that he had procured in Spain, ‘within which he proposed to enclose a spirit that would answer his questions’).11 All this is followed by the construction of a magic circle and the summoning of ‘Emperor Lucifer’ to appear ‘by the name of the great living God, his dear son and the Holy Ghost and by the power of Adonai, Elohim’, etc. The book then descends into a number of rituals involving further animal sacrifice, including boiling a cat, cutting the throat of a young wolf, and decapitating a frog, elements that render it one of the baser grimoires and a true book of sorcery with roots in primitive shamanism. (Needless to say, its prime value lies in an anthropological history of ideas within cultural context, not as an instruction manual—although that said, it did in fact become a source of working material for some forms of Caribbean sorcery).

17. The Magus: Written by Francis Barrett and published in 1801, this work was essentially a compilation of previous texts, mostly The Heptameron and Agrippa’s De Occulta Philosophia. Because it lacked original material it may be questioned why it is mentioned here, excepting for two reasons: it was very influential during a time when such writings had fallen out of vogue in many circles (owing mainly to the burgeoning scientific and industrial revolution); and it is a fact that most grimoires simply borrowed and/or modified from the contents of previous ones, so in that regard The Magus was not out of sorts.

18. The Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses: Despite occasional pretensions to antiquity, these are comparatively recent grimoires, probably first written in German in the 18th century, although the earliest known publication is dated to 1849 and the first English translation was in 1880. These books had some influence on African-American and Anglophone Caribbean occult traditions (such as Hoodoo, Voodoo, Obeah, and Rastafarianism).

The books purport to have been written by Moses (thus joining the standard pseudepigraphical tradition of grimoires) containing ‘secret’ occult lore that was allegedly hidden or removed from the Old Testament. In particular, the book derives its mythic power from the legend of the ‘magical victories’ of Moses over the Egyptian magicians, and how exactly he did this. The content is, as in all grimoires, concerned with the usage of occult means to gain personal advantages in one’s life.

Abracadabra

A concluding note on the word ‘abracadabra’. No word has been more commonly cited (and lampooned) in many cultures down through the centuries as a reference to mundane forms of magic. It many ways it is the symbol of folk magic par excellence, having its apparent origins in amulets and attempts to ward off disease and the evil spirits that were thought to be the causes of such illnesses. Daniel Defoe, in his Journal of the Plague Year (1722) mentioned it, stating that the common belief ascribed the plague to demons and a recipe for warding it off to the practice of writing ‘abracadabra’ in the shape of a descending triangle. These beliefs had apparently been brought to Britain by the Romans; reference to ‘abracadabra’ was made by the Roman doctor Quintus Sammonicus in 208 CE in which he prescribed usage of the word, written down on paper and tied around the neck, as a device to cure fevers.

One of the prescriptions involved wearing the charm around the neck for nine days followed by tossing it backward over the shoulder into a stream (from which probably derives the superstition of throwing salt over one’s shoulder if it is accidentally spilled).12 Multiple sources for the word have been speculated on, and while its origin is unknown, the most probable source appears to be Hebrew-Aramaic, in particular the expressions ibra k’dibra (‘I create through my speech’); abhadda kedkabhra (‘disappear like this word’); or Abra kadavra (‘I will create with words’).13 The word has also been connected to the Gnostic god Abraxis. Aleister Crowley altered it slightly to ‘Abrahadabra’, replacing the central ‘c’ with an ‘h’, which he connected to the Egyptian deity Horus, to the completion of the Great Work, and to the uniting of microcosm with macrocosm.14 Esoteric complexities aside, the central meaning of the word is clearly associated with creative force, and of the magician’s ultimate challenge to seemingly create something from nothing—in so doing, replicating the creative power of God.

One of the prescriptions involved wearing the charm around the neck for nine days followed by tossing it backward over the shoulder into a stream (from which probably derives the superstition of throwing salt over one’s shoulder if it is accidentally spilled).12 Multiple sources for the word have been speculated on, and while its origin is unknown, the most probable source appears to be Hebrew-Aramaic, in particular the expressions ibra k’dibra (‘I create through my speech’); abhadda kedkabhra (‘disappear like this word’); or Abra kadavra (‘I will create with words’).13 The word has also been connected to the Gnostic god Abraxis. Aleister Crowley altered it slightly to ‘Abrahadabra’, replacing the central ‘c’ with an ‘h’, which he connected to the Egyptian deity Horus, to the completion of the Great Work, and to the uniting of microcosm with macrocosm.14 Esoteric complexities aside, the central meaning of the word is clearly associated with creative force, and of the magician’s ultimate challenge to seemingly create something from nothing—in so doing, replicating the creative power of God.

Notes

1. Sarah Iles Johnston, Ancient Religions (Harvard University Press, 2007), p. 141.

2. Plato’s Charmides. See http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/charmides.html (accessed March 14, 2013). The whole relationship between science and magic is clarified in part via how the two traditions view the nature of words and language. Magic tends to regard particular language and words as intrinsically sacred and powerful, whereas for science they are more the product of human consensual agreement, mere constructs with no meaning beyond what we have assigned to them. See Stuart Clark, Witchcraft and Magic in Europe (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002), pp. 156-157.

3. Johnston, Ancient Religions, p. 143.

4. See Georg Dehn and Stephen Guth, The Book of Abramelin: A New Translation (Nicolas Hayes Inc., 2006). Dehn and Guth’s version corrects several errors found in Mathers’s version.

5. Gershom Scholem, Kabbalah (New York: Meridian Books, 1978), p. 186.

6. Richard Cavendish, The Black Arts (New York: Perigree Books, 1983), pp. 128-129.

7. The controversial modern magician and physicist Joseph Lisiewski, a sharp critic of post 19th century ceremonial magic and a practitioner and teacher of what he characterizes as ‘Old Magic’, considers The Heptameron pre-eminent as a working manual.

8. David Kahn, The Codebreakers: The Story of Secret Writing (New York: Macmillan Publishing, 1967), p.131.

9. Owen Davies, Grimoires: A History of Magic Books (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), p. 48.

10. Joseph H. Peterson, The Grimorium Verum (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2007).

11. Keith Thomas, Religion and the Decline of Magic (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1971), p. 230. For the matter of the alleged power of nails from the crosses of crucified men, see Richard Kieckhefer, Magic in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), p. 36.

12. Cavendish, The Black Arts, pp. 126-127.

13. Craig Conley, Magic Words: A Dictionary (San Francisco: Weiser Books, 2008), p. 66.

14. Crowley’s ideas on this word can be found in several of his works, especially Magick: Book 4, and 777 and Other Qabalistic Writings.

Copyright 2014 by P.T. Mistlberger and Axis Mundi Books, all rights reserved.