Note to the reader: the following is an excerpt from my book The Three Dangerous Magi: Osho, Gurdjieff, Crowley (Chapter 13, originally titled Why Remarkable Men Rarely Meet, and later Magical Warfare, which focuses on the controversial 1926 meeting between the notorious mystics G.I. Gurdjieff and Aleister Crowley). It is, as far as I know, the only comprehensive study of the meeting of these two men. Most accounts of the meeting blindly follow James Webb's 1980 version (which lacks sources). Even the best biographies on Crowley only have a few words to say about it, and Gurdjieff bios mention it only as yet another opportunity to disparage Crowley. The truth, as always, is more complex and more enigmatic.

I love the valiant; but it is not enough to wield a broadsword, one must also know against whom.

For often there is more valor when one refrains and passes by, in order to save oneself for the worthier enemy.

—Nietzsche (1)

The Beast 666 meets the Ambassador from Hell—or did he?

A relatively common fact of life is that renowned spiritual teachers only rarely meet each other, and even more rarely teach together. More commonly their teachings do not harmonize, and on occasion they appear to not even like each other. This is all due to many factors, not least of which is that they are usually busy people. More subtly there is often the case of the teacher’s ego, or more specifically, what is known as the “teacher-attachment” trait, the tendency for teachers to harden in their role as a teacher and minimize or ignore their own needs to socially and spiritually connect with peers. More insidiously their followers or students often collude in various ways with the teacher-attachment tendency, projecting the image of the ideal parent onto the teacher and contributing toward the teacher’s isolation. The followers, not wanting to share their “ideal parent” with others, in effect prevent the teacher from active relationships with other teachers, much like clamouring children can absorb most of the time and energy of their parents.

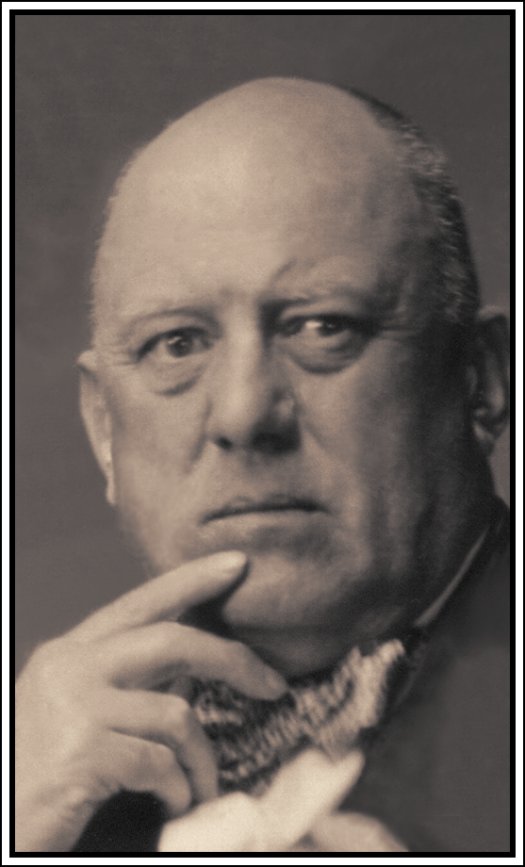

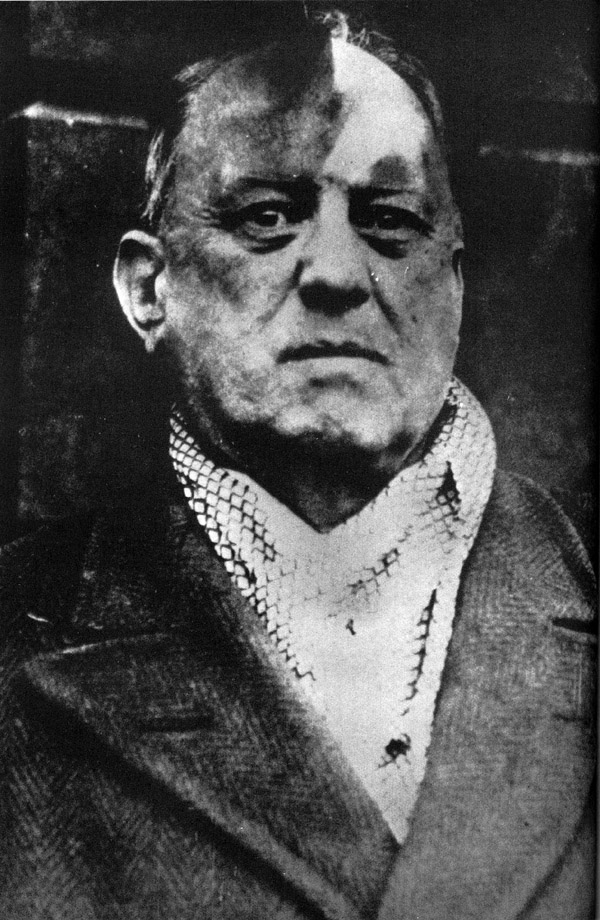

Crowley, however, was not always so busy, and unlike Gurdjieff and certainly Osho, he was not hemmed in by his own disciples, doubtless in part because he didn’t set himself up in anything remotely like a parental role (added to which, naturally, his abrasiveness was not precisely endearing). He is reported to have briefly met Gurdjieff in 1926 at the latter’s Prieure in Fontainebleau (about forty miles southeast of Paris). At the time Crowley would have been fifty years old and Gurdjieff somewhere in his mid-fifties—both a couple of well-aged wine Magi at that point. Crowley had been fond of Fontainebleau, having been there many times, as early as 1911, a decade before Gurdjieff arrived. A number of pages in his Confessions mention his periodic visits to this town. Just prior to Gurdjieff’s arrival and founding of his Institute in 1922 Crowley had leased a house in Fontainebleau in the winter of 1920. Shortly after this he left for Sicily where he was to found his Abbey of Thelema. By 1923 after the closure of the Abbey he left Sicily for Tunisia, and by the following year was back in Europe.

Stanley Nott, a student of Gurdjieff who authored two worthy books on his master, met Crowley in the summer of 1926 in Paris, and went on to describe the meeting of the two Magi themselves:

One day in Paris I met an acquaintance from New York who spoke about the possibilities of publishing modern literature. As I showed some interest, he offered to introduce me to a friend of his who was thinking of going into publishing, and we arranged to meet the following day at The Select in Montparnasse. His friend arrived; it was Aleister Crowley. Drinks were ordered, for which of course I paid, and we began to talk. Crowley had magnetism, and the kind of charm which many charlatans have; he also had a dead weight that was somewhat impressive. His attitude was fatherly and benign, and a few years earlier I might have fallen for it. Now I saw and sensed that I could have nothing to do with him. He talked in general terms about publishing, and then drifted into his black-magic jargon.

“To make a success of anything,” he said, “including publishing, you must have a certain combination. Here you have a Master, here a Bear, there the Dragon- a triangle which will bring results…” and so on and so on. When he fell silent I said, “Yes, but one must have money. Am I right in supposing that you have the necessary capital?” “I?” he asked, “No not a franc.” “Neither have I” I said.

Knowing that I was at the Prieure he asked me if I would get him an invitation there. But I did not wish to be responsible for introducing such a man. However, to my surprise, he appeared there a few days later and was given tea in the salon. The children were there, and he said to one of the boys something about his son who he was teaching to be a devil. Gurdjieff got up and spoke to the boy, who thereupon took no further notice of Crowley. There was some talk between Crowley and Gurdjieff, who kept a sharp watch on him all the time. I got the strong impression of two magicians, the white and the black- the one strong, powerful, full of light; the other also powerful but heavy, dull and ignorant. Though “black” was too strong a word for Crowley; he never understood the meaning of real black magic, yet hundreds of people came under his “spell”. He was clever. But as Gurdjieff says: “He is stupid who is clever.” (2)

A few observations can be made of Nott’s remarks. The time he met Crowley was not a high point in Crowley’s trajectory—he was past his prime and struggling with drug addictions. In that sense Nott’s repulsion with Crowley’s presence is not difficult to understand. Nott was a man who was working on himself and thus would have some degree of sensitivity. Crowley’s life experience and intellectual depth would have been readily apparent (hence the “magnetism” and “impressive dead weight” presence) but his suspect health, financial weakness, and relative isolation at that time would have also been apparent on subtle levels.

The bit about Nott “sensing” that he could have “nothing to do with” Crowley is interesting because it suggests that Nott has achieved some sort of grounding within himself that would allow him to take such a position against an obviously charismatic and persuasive personality (something Nott himself admits about Crowley). It takes a certain trust in oneself to stand up to a strong personality. However Nott’s reasons for adopting this position seem vague, unreasoned, and probably based partly on Crowley’s public reputation which was never particularly good.

And this is where Nott’s relative clarity appears to end. He is quick to pass judgment on Crowley’s lack of comprehension of “black magic,” yet offers no suggestion that he is truly familiar with Crowley’s life work (in particular his writings). Perhaps even more telling he seems to imply that Crowley actually was a black magician. Anyone truly acquainted with Crowley’s life work knows this is mostly nonsense. It is true that Crowley performed on occasion rites of ceremonial magic that involved the evocation of spirits from the “Goetia” grimoires—some of what are conventionally known as “demons” (though in reality they are simply the gods of older, vanquished civilizations)—and that on at least one occasion while in his early twenties he attempted to conjure some of these in some sort of misguided astral battle with his erstwhile mentor Samuel Mathers. (3) He also on another occasion claimed to be responsible for the sudden downfall of a publisher who had brought him grief. But in the epic sweep of Crowley’s life these small incidents have an almost comic interlude quality.

More to the point Crowley himself had a very sophisticated grasp of different levels of magic and clearly understood that evocation magic like that involving the Goetic energies, or the Abramelin work, is at core a psychological process in which the magician encounters deep elements of his own unconscious mind—essentially a type of shamanic journeying (regardless of whether we see the “spirits” involved as objectively real or not). Crowley also provided a very specific and uncompromising definition of black magic, a view consistent with the highest aspirations of the true mystic:

The Single Supreme Ritual is the attainment of the Knowledge and Conversation of the Holy Guardian Angel. It is the raising of the complete man in a vertical straight line. Any deviation from this line tends to become black magic. Any other operation is black magic. (4)

Interestingly Crowley’s view there is entirely aligned with Zen Buddhism, and its concept of makyo, a Japanese term that means “the devil in phenomena.” It refers to the idea that a seeker of enlightenment sitting in deep meditation will commonly encounter visions from his unconscious, some of which may be quite convincing and spectacular. No matter what, however, he is counselled by the Zen master to ignore these visions—all of which are regarded as makyo—and persist only in the one-pointed witnessing of all that arises in his field of consciousness, without attaching himself to anything. The point being that any phenomena that arises in the mind as an image or symbol is a distraction from ultimate truth. What Crowley calls the Holy Guardian Angel is what from one perspective at least (his later views of the HGA notwithstanding) Zen calls the Buddha-mind (the mind of ultimate truth). Nothing but that is a worthy goal for the true seeker. Crowley is in agreement with the Zen masters on that accord.

Given his teacher’s views it’s not clear what special understanding of black magic Nott was referring to. At any rate Nott’s observations are taken from his first book, Teachings of Gurdjieff: A Pupil’s Journal, which was published in 1961. Nott himself was born in 1887, which would have made him probably in his late sixties when he was putting this book together. Accordingly one can question the accuracy of the memory of his perceptions (even if based on diary notes) drawing on events that occurred thirty years before.

Nott followed up his account with an amusing anecdote apparently related by A. R. Orage, who was a close student of Gurdjieff’s and an established literary figure in England in the early 20th century. The story took place at an earlier time:

Orage said about this: “Alas, poor Crowley, I knew him well. We used to meet at the Society for Psychical Research when I was acting secretary. Once, when we were talking, he asked: ‘By the way, what number are you?’ Not knowing in the least what he meant, I said on the spur of the moment, ‘Twelve.’ ‘Good God, are you really?’ he replied, ‘I’m only seven.’” (6)

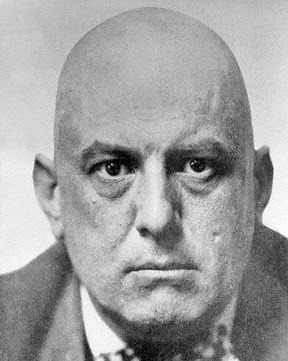

Crowley in Masonic regalia, and Gurdjieff's important student A.R. Orage

It’s a funny exchange, but little can be gleaned from it. Crowley may have just as easily been playing with Orage, as the other way around—or both men, equally renowned for their wit, may have been pulling each other’s leg at the same time. (Concerning Crowley’s reply to Orage, the esoteric significance of the number seven is of course legendary; Blavatsky’s Theosophy, which was the dominant occult paradigm at the time that Crowley and Orage met commonly discussed the number seven in its various doctrines, especially in relation to the seven subtle bodies of Man).

When initially researching this encounter of the Magi I was unclear as to when it took place, with some sources mentioning 1924, others 1926, but I soon realized that both dates were significant. This is because although Crowley met Gurdjieff only once, he in fact visited Gurdjieff’s school in Fontainebleau not once, but twice. One of Gurdjieff’s chief biographers, James Moore, has this to say about Crowley’s first visit, which took place in early 1924 when Gurdjieff was in America introducing his work in several major east coast cities:

In Paris Major Pinder met Gurdjieff with news that was, none of it, particularly good. A gaggle of undesirable voyeurs had visited the Prieure, including D.H. Lawrence (who thought it a “rotten, false, self-conscious place of people playing a sickly stunt”), and Aleister Crowley, the Beast 666 (who supposed Gurdjieff was a “tip-top man...a very advanced adept”). (7)

This is confirmed by Crowley’s biographer Lawrence Sutin, who noted that Crowley visited the Prieure on February 10th, 1924, and was received by Gurdjieff’s close student Major Frank Pinder.

The front gate of The Prieure. Of the Beast's 1926 visit, Moore wrote, "How Crowley gained entree is a mystery..."

Gurdjieff was in America from January to June of that year. Of his impressions of Gurdjieff and his work, Crowley had this to say in his diary, following his meeting with Pinder:

Gurdjieff, their prophet, seems a tip-top man. Heard more sense and insight than I've done for years. Pinder dines at 7.30. Oracle for my visit was “There are few men: there are enough”. Later, a really wonderful evening with Pinder. Gurdjieff clearly a very advanced adept. My chief quarrels are over sex (I doubt whether Pinder understands G’s true position) and their punishments, e.g. depriving the offender of a meal or making him stand half an hour with his arms out. Childish and morally valueless. (8)

These remarks of Crowley are interesting (and also amusing in their own right). The fact that Crowley recognizes Gurdjieff’s quality is significant, and is equally a testament to Major Pinder’s ability to explain his teacher’s work as it is to Crowley’s broadmindedness. The issue about sex is to be expected; Crowley’s attitude toward sex was a foreshadowing of the approach adopted later by the counterculture revolution of the 1960s, and more specifically, the psycho-spiritual atmosphere that later emerged from it, best represented by Osho’s work. However Gurdjieff approached the matter differently. His views were more classically Eastern, similar to Taoist or Yogic models where sex energy is regarded as a powerful force to be carefully regulated and conserved. Crowley’s view was essentially psychological, concerned mostly with deep exploration and the avoidance of repression at all costs. This is a more “left-hand Tantra” approach that is full of potential for both rapid growth, and rapid self-destruction, depending on how it is used. Crowley’s judgment that some Gurdjieffian methods are “childish and morally valueless” seems at first glance remarkably ironic—Crowley making pronouncements about morality? Crowley was also not averse to strict training methods, including harsh self-administered punishments for mental laziness, so his criticism here seems questionable.

As mentioned above, at the time of this meeting with Pinder, Crowley was already in his decline whereas Gurdjieff, despite being several years older, was near about at the peak of his powers. At the time of his early 1924 visit to Gurdjieff’s center Crowley was struggling with both heroin addiction and asthma attacks. (And in fact, the most likely reason he went to the Prieure in the first place was because of Gurdjieff’s reputation as a healer of drug addictions). His finances were depleted and he had little support. Gurdjieff, however, was energized by a lively spiritual ashram that he was deeply engaged in running, had a supportive following, and had just set sail along with thirty-five dedicated students to America to give his first public demonstrations of his sacred dances in major urban centers like New York City, Boston, and Philadelphia (a series of events that proved to be quite successful).

But all this was soon to change. It was immediately after returning to France in the summer of 1924—and just a few months after Crowley’s meeting with Pinder—that Gurdjieff had his famous car crash, in which he was seriously injured and very nearly died. (He was not an experienced driver having only learned to drive the year before).

He spent several weeks recuperating and when he emerged from his healing something in him had changed. He dismissed many of his students and began to focus more on his writing projects. It was exactly two years later, in the summer of 1926, when Crowley met with Stanley Nott (as recounted above) and made his second visit to the Prieure. His reasons for returning are unclear but it is significant that he returned at all. Clearly there must have been something in Gurdjieff’s school or teaching that interested him. Crowley had missed Gurdjieff during his 1924 visit, the latter being in America at the time, but in July of 1926, the two Magi met. Of this second visit, Gurdjieff's biographer James Moore wrote,

...a discordant note was struck by the brief unwelcome visit of Aleister Crowley -- 'The Master Therion', 'The Great Beast', the 'King of Depravity'. Scuttling between Paris and Tunis to shake off his creditors and find new ones, Crowley closed in on the Prieure from his Fontainebleau hotel, Au Cadran Bleu. How he actually gained entree is a mystery; 'Gurdjieffians' who previously met him (Orage, Pinder, and Stanley Nott) would never have sponsored him...the I Ching oracle had counselled the Great Beast to be 'patient, tenacious, modest, ashamed, friendly, affecting, tremulous and grateful', but this did not come easily; with his fishy eyes, rubbery androgynous face, outre dress, sinister rings, and 'sweet, slightly nauseous smell', Crowley was a noxious guest...' (Moore, 1991)

In addition to Nott’s account of this visit covered at the top of the chapter, there is this more dramatized version of the meeting, offered by esoteric historian James Webb, taken from his book The Harmonious Circle: The Lives and Work of G. I. Gurdjieff, P.D. Ouspensky, and Their Followers:

Crowley arrived for a whole weekend and spent the time like any other visitor to the Prieure; being shown the grounds and the activities in progress, listening to Gurdjieff’s music and his oracular conversation. Apart from some circumspection, Gurdjieff treated him like any other guest until the evening of his departure. After dinner on Sunday night, Gurdjieff led the way out of the dining room with Crowley, followed by the body of the pupils who had also been at the meal. Crowley made his way toward the door and turned to take his leave of Gurdjieff, who by this time was some way up the stairs to the second floor. “Mister, you go?” Gurdjieff inquired. Crowley assented. “You have been guest?”—a fact which the visitor could hardly deny. “Now you go, you are no longer guest?” Crowley—no doubt wondering whether his host had lost his grip on reality and was wandering in a semantic wilderness – humored his mood by indicating that he was on his way back to Paris. But Gurdjieff, having made the point that he was not violating the canons of hospitality, changed on the instant into the embodiment of righteous anger. “You filthy,” he stormed, “you dirty inside! Never again you set foot in my house!” From his vantage point on the stairs, he worked himself into a rage which quite transfixed his watching pupils. Crowley was stigmatized as the sewer of creation was taken apart and trodden into the mire. Finally, he was banished in the style of East Lynne by a Gurdjieff in fine histrionic form. White faced and shaking, the Great Beast crept back to Paris with his tail between his legs. (9)

This account by Webb was published in 1980 and cites no sources. Stanley Nott, who unlike Webb was a direct student of Gurdjieff’s and was present during Crowley’s visit, makes no mention of such an outburst from Gurdjieff. Lawrence Sutin questions whether such an event took place:

Webb portrays Gurdjieff’s triumph—and Crowley’s putative inner thoughts—with a heavy-handed novelistic touch. If this brutal banishment did occur, then it is remarkable that Crowley, who harbored animus toward so many rival teachers, never did so toward Gurdjieff. (10)

Therion and Beelzebub: Wizards of the West

While it is clear from Nott’s record that this meeting did in fact occur, as far as Webb’s version goes one would normally be inclined to agree with Sutin that it is unlikely that Crowley would make no mention of such rough treatment. (Although Crowley is silent on this matter, he did make disparaging remarks about Gurdjieff's famous pupil P.D. Ouspensky, calling him a "verbose, ignorant quack" in The Book of Thoth). There is however the question of timing, as Crowley’s published Confessions covers his life only up till 1924; the encounter with Gurdjieff took place in 1926. (Of course, Crowley kept diaries throughout his whole life, but it cannot be guaranteed that everything he wrote survived). Additionally Webb’s account is difficult to dismiss entirely because it is in keeping with Gurdjieff’s behavior and even his teaching methods. He was a volatile man in general. This account from J.G. Bennett describing the ordeal that Gurdjieff’s nephew Valentin endured while assisting the old magus in 1935 in Paris, gives a vivid depiction:

He also had to maintain his serenity in the face of Gurdjieff’s violent onslaughts, which were frequent and terrifying. Those who witnessed Gurdjieff’s rages can understand what it would mean to have been exposed week after week to them. His entire body would shake, his face would grow purple, and a stream of vituperation would pour out. It cannot be said that the anger was uncontrollable, for Gurdjieff could turn it off in a moment—but it was unquestionably real. (11)

Bennett goes on to add that he doubts that Gurdjieff’s anger was always a “teaching device” but that nevertheless in the case of his nephew it appeared to in fact strengthen him, if for no other reason because of the consciousness he developed in enduring it. That, of course, will not work in all cases. The line between Nietzsche’s “what does not kill me makes me stronger” and simple damage wrought by trauma is a fine one.

At any rate it should also be noted that between 1924 and 1926 Gurdjieff had gone through many taxing events—his car crash in the summer of 1924, followed by the death of his mother in the summer of 1925, and the difficult death of his young wife Julia Ostrowska in June of 1926 (he had tried hard to cure her of her cancer). In fact Gurdjieff’s wife passed away a mere couple of weeks before Crowley’s second visit to the Prieure and meeting with Gurdjieff. That fact alone would provide a possible explanation for Gurdjieff’s volatile behavior, if Webb’s account is by chance accurate.

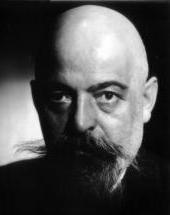

Gurdjieff's wife Julia Ostrowska, and James Webb

At the time of writing his book Webb was dealing with an encounter that took place over fifty years before; one wonders who his source was. Of James Webb himself a few interesting things can be noted: he was educated at the same place Crowley was (Trinity College of Cambridge), was only thirty-four years old when he published his The Harmonious Circle, and he committed suicide that same year (he had struggled with mental health issues). Webb was a brilliant young scholar who had written previous books on occultism, writings which included a discussion of the “rejected knowledge” syndrome, the idea that knowledge spurned by the rise of science ends up being the focus of esoteric, literary, or artistic circles, functioning as a kind of tool for rebellion against the Establishment. He titled his first book The Flight from Reason (later reprinted as The Occult Underground), in which he argued that much of the esoteric revival of the late 19th and early 20th century was based on a revolt against insignificance, a need to re-assert the primacy of Man that had been dealt a serious blow by the scientific method. Webb’s largest work (The Harmonious Circle) was his last, in which he spent eight years researching and writing about Gurdjieff and the Work. He made many contacts in the worldwide Gurdjieff community and became deeply involved in the matter of his subject. That said, he remained fundamentally an outsider, an investigative journalist—not one who was actually doing the inner work. (12)

It is difficult to conclude much about his account of the meeting of the Magi. Because he did not mention his sources for it, and because his account differs so much from Nott’s, the accuracy of his version must be considered suspect. However, Webb was unquestionably a sincere researcher. I suspect that he actually did hear a story with some basis in reality that had been passed down, but one that after fifty years had suffered the usual distortion. What he likely reported was that “fish story.” And it must also be pointed out that Webb himself, right in the Preface to The Harmonious Circle, cautioned against the risks of always assuming literal truth behind the tales:

The Historian must separate hard historical fact from evidence of another sort. Individuals 'in the Work' are often unreliable sources of historical information...the reader should be warned that -- despite constant vigilance -- incidents may have crept into these pages which were intended as fables illustrating particular points, or even as moral allegories directed at the author. (13)

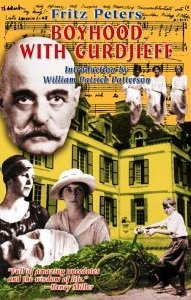

Unfortunately Webb’s version has been passed around apparently without much consideration by some. William Patrick Patterson, who has written several books on Gurdjieff’s life, simply repeats verbatim the Webb version of the meeting of the Magi in his otherwise excellent video documentary Gurdjieff’s Legacy (Arete Communications, 2003), even referring to Crowley as “the black magician” and suggesting that Crowley chose to visit the Prieure just a few weeks after Gurdjieff’s wife’s death as he “may have sensed a psychological weakness” in Gurdjieff at that time (which is almost certainly untrue). Finally, an even more outlandish version (complete with the requisite distorted Crowley legend) of the famous meeting was recorded by Fritz Peters:

Many years ago, Alistair [sic] Crowley, who had made a name for himself in England as a “magician” and who boasted, among other things, of having suspended his pregnant wife by her thumbs in an effort to produce a monster-child, made an unsolicited visit to Gurdjieff at Fontainebleau. Crowley was apparently convinced that Gurdjieff was a “black magician” and the ostensible purpose of his visit was to challenge Gurdjieff to some sort of duel in magic. The meeting turned out to be anti-climactical as Gurdjieff, although he would not deny his knowledge of certain powers that might be called “magic” refused to demonstrate any of them. In his turn, Mr. Crowley also refused to “reveal” any of his powers so, to the great disappointment of the onlookers, we did not witness any supernatural feats. Also, Mr. Crowley departed with the impression that Gurdjieff was either (a) a fake, or (b) an inferior black magician. (14)

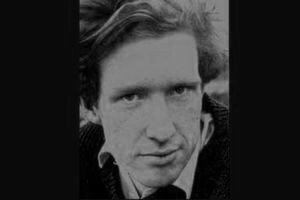

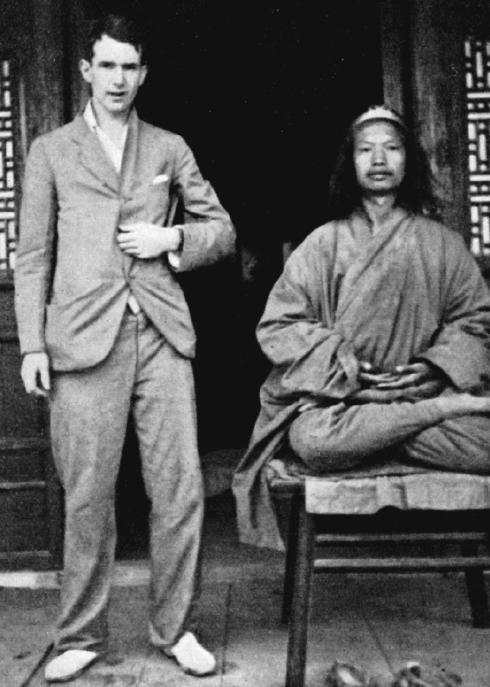

Fritz Peters at the Prieure in 1926 around the time Crowley and Gurdjieff met, with Gurdjieff's student, the operatic soprano and actress Georgette LeBlanc

Peters is primarily known for his book Boyhood with Gurdjieff, which describes five years he spent with Gurdjieff at the Prieure from 1924 to 1929. Peters was born in 1913, so these years encompassed his boyhood period of age eleven to sixteen. He published the above account in 1965 but he was only thirteen when Crowley met Gurdjieff. As a result his view of the Crowley-Gurdjieff encounter is understandably childlike, doubtless distorted by banal gossip and probably the dim memory of an event that occurred forty years prior to his writing about it. For one thing the idea that Crowley, suffering from heroin addiction and broke at the time, would have sought out some sort of “magic duel” is ludicrous. For another, the notion that Crowley thought Gurdjieff a “charlatan” is completely refuted by Crowley’s own words from his diary, referring to Gurdjieff as an “advanced adept.”

Paul Beekman Taylor, an English professor and one of the more rigorous Gurdjieff scholars, was very critical of Peters' two books on Gurdjieff:

Peters himself, when challenged later in his life by those who

questioned his 'fact', would invariably reply: 'I am a novelist, not a

historian.' His Boyhood With Gurdjieff is replete with both

misinformation and invention, much of which has been discarded tacitly

as error, but much of which is taken as 'fact.' (15)

And as a fitting anticlimax to these breathless depictions of the meeting of the Magi, we have the following description from Gerald Suster:

It was Yorke who gave me an accurate account of the meeting between Crowley and another celebrated magus, G.I. Gurdjieff, for he was the only other person present. There are a number of false versions…according to Yorke, Crowley and Gurdjieff met in Paris for about half an hour and nothing much happened other than a display of mutual male respect: “They sniffed around one another like dogs, y’know. Sniffed around one another like dogs,” Yorke chuckled. (16)

Yorke in China in 1933; right, Gerald Suster

Gurus at War

The meeting of Crowley and Gurdjieff fascinates for many reasons that go far beyond the amusingly mundane nature of the alleged encounter and the various (often absurd) psychological projections of those describing it, not least of which is that it makes one consider the actual similarities of the two men. Both were noted for their appearance (shaven heads during a time when shaven heads were not fashionable, and penetrating gaze); both had been world travelers and intense seekers; both had magnetic personalities and the ability to hold the attention of others; both were brilliant and capable of being conniving and manipulative with the best of them; and both ultimately formulated their own very unique system, based on not just the accumulated wisdom of the traditions they’d studied in, but also their own carefully thought out attempt to guide humanity to its next level of evolution. Both were concerned, fundamentally, with planetary aims, far beyond mere personal aims.

On a sheer human level they even shared a common dark chapter on their journey: they both briefly considered suicide during difficult phases of their middle-aged years: Crowley in 1923 shortly after the collapse of his Cefalu commune and his expulsion from Italy; and Gurdjieff in late 1927, upon suddenly realizing that the book he had been laboring on for three straight years (Beelzebub) was unreadable and needed a stylistic re-write. (17)

It is always interesting to note how often gurus steer clear of each other, like big alpha dogs marking out psychic territory. One would think that there would be plenty of common ground in which to establish a higher brotherhood of sorts—or at the very least, demonstrate active curiosity in each other’s teachings. But in truth this rarely happens. Amongst the usual reasons offered— they have limited time, are meant to work only with specific conceptual models, practical methods, and particular souls, etc.—is also the more natural one, being that they themselves simply do not want to.

To their closest admirers both Crowley and Gurdjieff were held to be nothing short of supernatural—Crowley the “prophet” of a “new Aeon” selected by advanced intelligences, the herald of a coming good; and Gurdjieff (who actually wrote a book called The Herald of Coming Good) (18) a “planetary or solar god” (to use Orage’s term) come to offer a crucial spiritual dispensation for humanity. What then prevents them— and other gurus—from being more outwardly connected to each other?

The issue has much to do with the dynamics of spiritual power. As an interesting case study we can briefly consider here the saga of the Indian Advaita master Harilal Poonja—the elderly guru who received a number of Osho’s disciples after Osho’s death in 1990—and his one-time American student Andrew Cohen (who had never been an Osho disciple). Cohen, an American from New York, met Poonja in 1986 in Lucknow, India. At the time Cohen was around thirty years old, a former musician and a sincere spiritual seeker. As an adolescent he’d had a peak spiritual experience in which he’d tasted non-duality or the essential Oneness of life, in a manner that was potent enough to remain with him as a profound memory for many years, always to remind him of the possibilities inherent in human life. He pursued interests such as martial arts and music but remained fundamentally dissatisfied. While in India he sought out and found Poonja who at the time was in his mid-seventies and although very respected as an awakened master by those who knew him, was basically low profile and unheard of in the West. Cohen spent a short time with Poonja, a few weeks, and while with him underwent a powerful satori (the Zen term for “sudden awakening”) in which he clearly realized non-duality, most notably between Poonja and himself. This was underscored in his first book published not long after, titled My Master is Myself. (19)

That very description—my master is myself—lies at the heart of the ancient Eastern tradition of “guru-yoga,” something found in both Hindu and Tibetan Buddhist traditions. The essential idea behind it is to see that the spiritual teacher is, in principle, a reflection of the awakened self within the seeker. To regard one’s teacher as the “buddha-mind” as they put in some Buddhist traditions, is a generally trustworthy way to accelerate one’s spiritual progress, because it gives a good opportunity to subdue the ego, which by nature does not trust in the higher values represented by the guru’s teaching and seeks to maintain separation and ego-identity at all costs. (This was also the rationale behind Osho’s “device” of creating lockets for his disciples containing a photo of himself).

Of course it is a given that such an approach carries a risk factor, because to regard one’s teacher as a reflection of one’s awakened self assumes that the teacher is a worthy representative of such. But a subtler point behind guru-yoga is that it has the power to override “imperfections” in the guru. Put simply it is possible to attain significant spiritual realization in the company of a flawed teacher. Likewise, it is also possible to experience considerable disillusionment and pain when associating with a teacher who turns out to have greater character flaws than one might have initially imagined.

Cohen eventually had a falling out with his master -- largely over his perception that Poonja's behavior was seriously out of alignment with what he taught -- documented in his unusually honest (and somewhat harsh) book Autobiography of an Awakening. (20) His decision to turn against his guru , and the subsequent backbiting that went on from both sides of the Poonja-Cohen camps, was reminiscent of a somewhat nastier version of Ouspensky’s separation from Gurdjieff. In both cases the student (Ouspensky and Cohen) decided that they’d seen and gathered enough subjective evidence that the teacher (Gurdjieff and Poonja) had serious character defects that compromised their work too much.

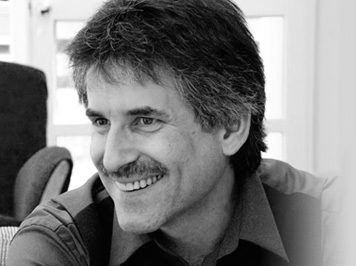

Andrew Cohen and H.W.L. Poonja

Poonja died in 1997 at the age of eighty-six; ironically, in the last decade of his life he became very well known and attracted hundreds of devoted Western students, largely because of the publicity generated for him by Andrew Cohen. Many, if not most, of these students were former disciples of Osho who sought out a “living master” after Osho’s death in 1990. The jury remains out on the quality of character of both Poonja and Cohen, but anyone who studies their respective teachings will be struck by a simple fact: both were/are passionate teachers with skill, and both have inspired (and awakened, to some extent) many.

Cohen, as the younger of the two men, has met with criticism for what some perceive as a deeply disrespectful attitude toward an elderly teacher, but it can be argued that Cohen has more than compensated for that (if indeed such even needs compensation) by seeking out and engaging in a broad range of dialogue with many established spiritual teachers. For that alone he is to be commended, if only because of the rarity of it. As mentioned at the top of this chapter, spiritual teachers, especially well-established ones with a loyal following (regardless of the size of the following) very rarely spend any significant time with other teachers. Cohen has been a vivid exception to that trend. He has even taken it one step further by engaging in a series of dialogues and co-teaching seminars with the well-known American writer and theorist of consciousness studies, Ken Wilber.

Cohen’s story, though mired in controversy and discord in his relationship with his root-teacher, is nevertheless a rarity in that he appears to be the first so-called “enlightened” teacher in modern times to actively pursue dialogue with other teachers and even to co-teach with one of them. Psychological interpretations of this would be easy to come by, an obvious one being that Cohen may have been seeking to heal his relationship with the father-archetype (and thus vicariously with his now dead former guru), but nothing negates the fact that he has set an interesting and very unusual example.

A less involved and more amusing version of odd teacher-teacher dynamics can be found in the relationship between Osho and J. Krishnamurti. The latter was born in 1895, almost two generations before Osho, but during the 1960s and 70s they were probably the two most popular and notorious gurus in India. To use the term “relationship” to describe their dynamic is being generous—the two never met in the flesh. But as extremely high profile gurus they were often exposed to each other’s teachings or disciples, and frequently commented—often harshly—on each other. (These mutual insults reached something of a climax in the 1980s when Krishnamurti referred to Osho as a “criminal.”)

Krishnamurti and Osho, around 1970

In 2007 I was invited by the Theosophical Society in Toronto to give a talk and run a day-long workshop for about twenty-five of their local members. While there I had a chance to have a talk with a Mr. Pattal, the president at that time of the Toronto chapter, who hailed from India and who remembered the heady days of the late 1960s when Osho and Krishnamurti were the two main “stars” of the guru-circuit in Bombay. He told me how seekers would gravitate from one to the other and of the subtle rivalries that would ensue. It has always been a long standing paradox that gurus who teach divine principles are themselves often seemingly light years apart, a fact that often confuses their followers and in worst case scenarios leads to the creation of rival religions that then usurp the original intention behind the creation of a spiritual community gathered around a teacher, wielding it instead as a weapon against the followers of the rival prophet. The Gurdjieff-Ouspensky split was a textbook example of that.

Krishnamurti’s life spanned most of the 20th century and reads like the archetypal tale of a “chosen one” who is fated from a young age to be an outsider. Groomed by the leaders of the Theosophical Society, that highly influential but uneven metaphysical organization founded in 1875 by Helena Blavatsky and Henry Steel Olcott, Krishnamurti was supposed to be an incarnation of a great world teacher, a type of Second Coming (sometimes compared to Maitreya, the “next Buddha” of Buddhist canon). At the last moment Krishnamurti rebelled against this cosmic destiny, rejected the whole plan, and spent the next sixty-plus years wandering the world as a fiery, iconoclastic, and profound teacher of spiritual awakening.

No doubt in part for his rebellious spirit, as well as the obvious quality of his understanding, Krishnamurti earned Osho’s abiding interest and deep respect. When Krishnamurti died in 1985 at the age of 90, Osho remarked:

He has died, and it seems the world goes on its way without even looking back for a single moment that the most intelligent man is no longer there. It will be difficult to find that sharpness and that intelligence again in centuries. But people are such sleep walkers, they have not taken much note. In newspapers, just in small corners where nobody reads, his death is declared. And it seems that a ninety-year-old man who has been continuously speaking for almost seventy years, moving around the world, trying to help people to get unconditioned, trying to help people to become free—nobody seems even to pay a tribute to the man who has worked the hardest in the whole of history for man's freedom, for man's dignity.

Those highly laudatory words were soon followed by less flattering observations from Osho:

Krishnamurti failed because he could not touch the human heart; he could only reach the human head. The heart needs some different approaches. This is where I have differed with him all my life: unless the human heart is reached, you can go on repeating parrot-like, beautiful words—they don't mean anything. Whatever Krishnamurti was saying is true, but he could not manage to relate it to your heart. In other words, what I am saying is that J. Krishnamurti was a great philosopher but he could not become a master. He could not help people, prepare people for a new life, a new orientation. (21)

These comments of Osho are problematic, given the benefit of hindsight. Osho may indeed be accurate in diagnosing Krishnamurti’s weakness, but it’s also apparent that the “less heart-oriented” Krishnamurti did not leave behind a legacy of unsavory elements like the Oregon-Rajneeshpuram fiasco. The point that can be taken there is that “ability to touch the human heart” can be a double-edged thing as is generally the case whenever passion is awakened. Krishnamurti was undeniably passionate but he did not have Osho’s interest in cultivating close relationships with disciples, nor in setting up a large organization. So while Krishnamurti’s approach remained much dryer and less involved interpersonally with followers, he also never had to deal with the immense disappointment that accompanies the destruction of a large commune and the dismantling of an entire vision.

The very paradox of the spiritual teacher is never better illustrated than in the interplay between Osho and Krishnamurti, both being seen as deeply enlightened by their followers (as well as by non-followers) and yet both having utterly different means by which to share their insights with humanity. Krishnamurti was dead-set against the type of guru-disciple relationship cultivated by Osho. He preached autonomy of spirit above all else, whereas Osho, particularly between the period of 1970-85, worked in a framework that was very much based on guru-yoga, where a deep level of trust and surrender is required by the disciple. After all this was a man who not only gave personally crafted initiate names to each of his followers but also had them wear a locket around their necks containing a photo of himself. Seen by a disinterested outsider such practices must have seemed deeply cultic, reinforcing dependency on the guru and little else. Experienced from the inside, however, the power of the process can never be underestimated. Guru-yoga is a potent and potentially deeply transformative practice because it allows for a vehicle in which certain elements of ego can be quickly vanquished, like fear, distrust, exaggerated independence, control tendencies—the list of undesirable traits that can be evaporated by an inwardly surrendered relationship with an authentic guru is almost endless.

However, all practitioners of faith-based traditions argue something similar. One need look no further than the tradition of the “born-again” Christian. The point can be made that most faith-based paths differ from guru-yoga with a living master, being based on trust in a dead master, which is arguably much easier. Strong, living gurus are notoriously disruptive, and at best, not polite. To be near them is to be near a fire, and to be “calcified” and “dissolved” as the terms from alchemy have it—to be cooked in the heat and penetrating light of clear vision.

History is full of terrible examples of those who have “surrendered” to a spiritual authority, only to turn out to be the latest example of intolerance and narrowness of understanding. Thus, guru-yoga and anything requiring the overriding of critical faculties by “trust” and “surrender” is intensely double-edged, because the point can be made that such a practice is really only intended for a mature seeker, one who can recognize clearly just what they are putting their trust in.

At any rate, the distance between Krishnamurti and Osho was great not just because of dissimilar character but because their very method and approach to the matter of awakening souls was almost diametrically opposed. And yet it can be easily argued that both shared a common level of understanding. The whole thing illustrates, once again, that enlightenment—the realization of truth—and the teaching of it, by whatever means, bear little relation. And this must be seen as one natural cause behind the typical disconnect between spiritual teachers.

Crowley and Gurdjieff may not have had much of a meeting back in 1926 in Fontainebleau, but the matter is likely academic. Even if their meeting had been more substantial the odds that they would have agreed on much are very small. Even more likely is that the more they would have talked, the more they would have disagreed—not necessarily about core-level truths, but about the all-important matter of how to implement them, and above all, how to teach them.

Notes

1. From Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Walter Kaufman, The Portable Nietzsche (New York: Penguin Books, 1982) p. 321.

2. C.S. Nott, Teachings of Gurdjieff: A Pupil’s Journal (London: Penguin Arkana, 1990), pp. 121-122.

3. Crowley used standard “Solomonic” ceremonial magick. This generally involves a magician sitting in a circle that is fortified with holy names (usually Hebrew). Outside the circle is the “triangle of art,” in which is usually a piece of glass that is painted flat black, and functions as a device to gaze upon. Various magical formulae are spoken or chanted, placing the seer or magician into an altered state of consciousness. What follows then may variously be understood as shamanic journeying, communication with discarnate intelligences, or what Jung called active imagination, that is, direct communication with elements of one’s own subconscious mind. However understood, the point is to gain mastery over aspects of one’s own self as one encounters whatever experience may unfold in the ceremony. Lower forms of this type of magic involve evoking entities to gain power over situations in one’s life, or even over others. Crowley did on occasion explore this type of “low magick,” but overwhelmingly he was concerned with the invocation of the Holy Guardian Angel, or Higher Self—i.e., High Magick. The classic grimoires dealing with Solomonic Magic are generally recognized to be The Key of Solomon the King, edited by S.L. MacGregor Mathers (Mineola, Dover Publications, 2009); The Goetia: The Lesser Key of Solomon the King, translated by S.L. MacGregor Mathers and edited and introduced by Aleister Crowley (Austin: Ordo Templi Orientis, 1997); and The Book of the Sacred Magic of Abramelin the Mage, translated by S.L. MacGregor Mathers (New York: Dover Publications, 1975).

4. Aleister Crowley, Magick: Book Four, Liber ABA (Weiser Books, revised edition 1998 is the most recent), Chapter 21.

5. P.D. Ouspensky, In Search of the Miraculous: Fragments of an Unknown Teaching (Orlando: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc., 1949), pp. 226-227. Gurdjieff was also accused of being a black magician by some. Rom Landau compared him to Rasputin. See www.gurdjieff.org/munson1.htm

6. C.S. Nott, Teachings of Gurdjieff: A Pupil’s Journal, p.122. Although Nott is generally regarded as a writer of integrity, he was far from an error-free historian. Paul Beekman Taylor claimed Nott was 'often hazy on dates'. He mentions some of Nott's factual errors in his web article Inventors of Gurdjieff. See http://www.gurdjieff.org/taylor1.htm

7. James Moore, Gurdjieff: Anatomy of a Myth (Rockport: Element Books, 1991), p. 204.

8. Lawrence Sutin, Do What Thou Wilt: A Life of Aleister Crowley (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2000) p. 317.

9. James Webb, The Harmonious Circle: The Lives and Work of G.I. Gurdjieff, P.D. Ouspensky and Their Followers (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1980), p. 315.

10. Sutin, Do What Thou Wilt, p. 318. In an email exchange I had with one well established author who had been in the Gurdjieff Work for twenty years, he told me he had knowledge of Webb's source, but was not free to reveal it. He said that he believed that Webb's version was essentially accurate. He added, "Gurdjieff did not mistreat Crowley. Gurdjieff rightfully sent Crowley away." That said, Webb's numerous factual errors in his biography of Gurdjieff have been outlined by Paul Beekman Taylor. See http://www.gurdjieff.org/taylor1.htm

11. J.G. Bennett, Gurdjieff: Making a New World (Santa Fe: Bennett Books, 1992), p. 168.

12. Reading Webb’s The Harmonious Circle, that becomes clear. It is a monumental work on a scholarly level, particularly the latter section of the book where he unearths some of Gurdjieff’s likely sources for the theory of his System. And yet the intense intellectuality of the work suggests a person out of balance, one longing to penetrate the teachings but unable to make the move from scholarly observer to actual participant. This has long been the key point that differentiates the mystic from the scholar. The former participates directly in the transformational work (regardless of “success”), the latter watches and takes notes (although, it goes without saying, that it is entirely possible to be both mystic and scholar).

13. Webb, The Harmonious Circle, p. 14.

14. Fritz Peters, Gurdjieff Remembered (New York: Samuel Weiser, 1971), pp. 67-68.

15. See http://www.gurdjieff.org/taylor1.htm

16. Gerald Suster, The Legacy of the Beast: The Life, Work, and Influence of Aleister Crowley (York Beach: Samuel Weiser, 1990), pp. 92-93. Especially amusing is the “sniffing” reference, being naturally associated with dogs. Gurdjieff used the dog as a symbol of a man dying before he “makes a soul.” In many cultures the dog is often symbolically associated with death. That aside, the Yorke anecdote only enhances the mystery as Yorke did not first meet Crowley until New Year's Eve, 1927 (Kaczynski, Perdurabo, p. 427) -- eighteen months after Crowley's reported encounter with Gurdjieff at Fontainebleau.

17. For Crowley’s suicidal thoughts, see Sutin, Do What Thou Wilt, p. 311; For Gurdjieff’s, see G.I. Gurdjieff, Life Is Real Only Then, When I Am (London: Penguin Arkana, 1999), pp. 33-34; or Moore, Gurdjieff: Anatomy of a Myth, p. 222.

18. It was published in 1933 but later repudiated by Gurdjieff and withdrawn from circulation. It is now available again from Book Studio, most recent edition 2008. Webb (1980) suggested that the book revealed Gurdjieff’s shadow side, namely, his capacity to manipulate. For an interesting short essay on the book, see Sophie Wellbeloved, Gurdjieff: The Key Concepts (London: Routledge, 2003), pp. 92-94.

19. Andrew Cohen, My Master is Myself: The Birth of a Spiritual Teacher (Larkspur: Moksha Press, 1989).

20. Andrew Cohen, Autobiography of an Awakening (Corte Madera: Moksha Foundation, 1992).

21. www.oshoworld.com/biography/innercontent.asp?FileName=biography9/09-09-krishnamurti.txt

Copyright 2009, P.T. Mistlberger, all rights reserved.