Essays in this section center on the theme of what C. G. Jung called the 'Shadow', the hidden dark element of the subconscious mind, and the need to transmute its energies in the cause of individuation and awakening. The first two essays are excerpted from my book The Inner Light: Self Realization via the Western Esoteric Tradition (Axis Mundi Books, 2014). They deal with the themes of shadow elements within the Western esoteric tradition and how they have reached a distorted expression in fictional literature and film, such as via Frankenstein, vampires, and werewolves, each of which can be understood as the 'lower octave' of the Body of Light, tantric communion, shapeshifting/deity yoga, and other legitimate esoteric practices of the great initiatic traditions.

and the Assumption of God-forms

by P.T. Mistlberger

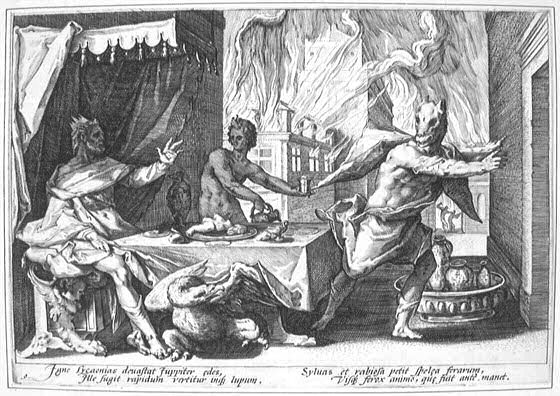

No sooner were these placed on the table than I brought the roof down on the household gods, with my avenging flames, those gods worthy of such a master. He himself ran in terror, and reaching the silent fields howled aloud, frustrated of speech. Foaming at the mouth, and greedy as ever for killing, he turned against the sheep, still delighting in blood. His clothes became bristling hair, his arms became legs. He was a wolf, but kept some vestige of his former shape. There were the same grey hairs, the same violent face, the same glittering eyes, the same savage image.

—Ovid’s Metamorphoses (I:199-243)

Even a man who is pure in heart

And says his prayers by night

May become a wolf when the wolfsbane blooms

And

the autumn moon is bright

—from The Wolfman (1941)

The main argument of this essay is that

the popular mythology of the werewolf that has largely been propagated

in modern times by the Silver Screen, beginning with the 1941 film The Wolfman and followed by a host of

derivates, is indeed based on an actual worldwide legend—however this legend is

ultimately a debased form of certain legitimate practices within the ancient

spiritual tradition known as ‘shamanism’. These practices, in turn, are

primitive versions of advanced mystical practices known in some Western

esoteric traditions as the ‘assumption of god-forms’ and the ‘knowledge and

conversation of the Holy Guardian Angel’, and in certain Eastern traditions as

‘deity yoga’. Above and beyond all that, the idea of the 'were-animal' (of whatever species) represents a good representation of what C.G. Jung meant by the 'shadow', the element of repressed animalistic impulse hidden in the subconscious of most people. Arguably this element is as strong, or stronger, in so-called spiritual seekers, because the very striving for light and understanding carries the risk of bringing about an imbalance resulting from the denial of impulse and so-called darkness.

The

Wolfman and Derivates

Of the three chief icons of 20th

century horror films—Frankenstein’s monster, Dracula, and the Wolfman—only the

latter deals directly with an animal life-form. Unlike Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) or Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1887), there was no ‘source

text’ of fiction to kick start the werewolf film industry. Movies involving

werewolves appeared as early as 1913, but the iconic horror image of the

bipedal, fanged, tormented, cursed- under-the-full-Moon werewolf did not appear until the

1935 film The Werewolf of London,

with Henry Hull. (The makeup artist for this movie was Jack Pierce, the very same

artist who made up Boris Karloff for his iconic role in 1931’s Frankenstein). The film had an original

plot, with the lead character getting bit by a werewolf while in Tibet

procuring a type of plant. Later, back in London,

the man becomes a werewolf himself, and then kills a young woman, both themes

common to classical werewolf legends (see below). The Werewolf of London appeared a few years after the original Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931), at the

time was regarded as a derivative of it, and accordingly did not sell many

tickets.

The

Wolfman (1941), starring Lon Chaney Jr. (image on the right) is

credited with perpetuating the most common werewolf stereotypes, including a

man who is bitten by a werewolf and subsequently becomes one himself,

transformations under a full Moon, and murders committed at night by a

tormented werewolf that are subsequently mostly forgotten in the morning. This

movie also featured the metal silver, in the form of a silver walking cane with

a wolf emblem purchased by Lon Chaney’s character at the beginning of the

movie. The film did not, however, feature silver bullets.

A series of werewolf copy-cat movies, many

of them bad, subsequently appeared in the 1940s and again in the 1960s and 70s.

The decade of the 1980s was the modern ‘golden age’ of quality werewolf films,

beginning with The Howling (1980), followed

by An American Werewolf in London

(1981), and perhaps the most stylish werewolf movie ever done, Neil Jordan’s The Company of Wolves (1984), which was an

elaboration of Grimm’s Little Red Riding

Hood fable. Early 21st century efforts have included Ginger Snaps (2000), and the multiple Underworld and Twilight films, two series which were box office successes but

generally derided by critics. (Underworld

in particular seemed little more than a Matrix

derivative).

Two original and interesting films that

dealt with the werewolf theme but did not specifically involve werewolves, were

Wolfen (1981), based on Whitley

Strieber’s 1978 novel about a pack of relatively advanced entities resembling

wolves terrorizing urban slums; and Brotherhood

of the Wolf (France, 2001), based in part on the true story of ‘the Beast

of Gévaudan’, concerning an alleged wolf-like creature (or creatures) killing

people in a region of southern France during the 1760s. The latter film appears also

to have taken its lead from the notorious ‘Leopard-Man’ killings of Nigeria

during the 1940s (for both stories, see below). The movie has a twist at the

end that involves a trained creature being used as a pawn by a secret society

bent on overthrowing the king.

Werewolves in Lore

The word ‘werewolf’ originates in the Old

English terms wer (‘man’) and wulf (‘wolf’); the word has been in use

as far back as 1000 CE. The wolf

throughout history has served as an intense mirror for human nature because as

much as any other animal it has been seen in a heavily polarized light. On the

one hand, it has been associated with the antisocial and the disloyal, along

with savage impulse, lack of conscience, and outright evil. On the other hand

it has also been connected to bravery, loyalty, and the power of team-work,

family, organization, or nation (the ‘pack’) to overcome obstacles. This is an

obvious metaphor for human nature. What marks the psychology of the human being

as much as anything is the division between the polar potentials for sublime

wisdom and nobility of character alongside the capacity for sheer self-centered

depravity and destructive malice.

The earliest recorded mention of humans

changing into wolves is from ancient Greek literature, in specific from the

Balkan area known as Arcadia.

Legend has it that this land was ruled by a king named Lycaon (circa 1500 BCE),

who also promoted the worship of Zeus. (The Eastern timber wolf derives its

scientific nomenclature—Canis lupus

Lycaon—from this Greek legend). Lycaon’s sons—according to some versions of

the myth there were as many as fifty of them—like typical privileged offspring,

were reportedly subversive and arrogant. This matter came to Zeus’s attention

who decided to monitor them ‘undercover’, disguised as a common worker. In a

visit to Lycaon’s house the undercover Zeus was fed a vile mix of flesh from a sacrificed

human child and animal entrails (the purpose being to determine if the stranger

was actually Zeus). Angered at the murder of the child, Zeus turned Lycaon into

a wolf. Some versions of the myth have him turning all his sons into wolves as

well; other versions have him killing the sons with a lightening bolt. (It is

from this legend that the technical term for werewolfery, ‘lycanthropy’,

derives).

From this myth we can see the coincidental nature of the association of the wolf with evil intent. At the simplest level, werewolf legends are in part a reflection of the reality of sharing a territory with a particular predator. Prior to the human depredations of wolves of the 20th century, the wolf was the dominant predator in Europe alongside Man. Predictably, it is from these lands that the werewolf legend has been strongest (such as in Scandinavia, for example). In India there has been the belief in the weretiger, in South America the werejaguar, and in Japan the werefox, and so forth.

In Africa,

there have been the wereleopards and werelions. Belief in the former was famously

found amongst a group calling itself the Leopard Society—eighteen members of

which were executed in Nigeria in 1946 for ‘terrorizing’ a town, in which up to

two hundred victims appeared to have been mysteriously killed by man-leopards.1

The matter of werelions came to light in a series of arrests in 1947 in

Tanganyika (today part of Tanzania) in which close to seventy ‘Lion Men’ were

accused of carrying out various acts of mayhem (including murder) while dressed

up in lion skins and leaving wounds resembling marks from lion claws. These

acts, some of which were ritualistic, were in some instances motivated by the

ancient theme of blood-sacrifice, where the belief is that by a ritualistic

killing certain merits will be achieved and blessings accorded from deities

(such as good weather, crops, hunting, and other benefits).2

Werewolf killings have traditionally been of the lurid sort, often involving sexual depravities and the eating of human flesh (commonly of the young and/or female). Doubtless for a significant number of these cases the root of the matter was straightforward: mental illness (including hallucinations) and psychopathic behavior.3 But in cases where these stories are mere legend, or delusions or fabrications extracted under torture (common during the various Inquisitions), the sources of this appear to be connected to old beliefs around the power, or other attributes, that can be obtained by consuming the flesh or blood of an enemy or other victim with desired qualities. (As far back as Plato this idea has been used as an allegory to warn about the likely end result: in The Republic, Socrates’ forecast that any leader who plots to eliminate a political rival—for which he uses the metaphor ‘tasting human flesh’—will himself become a tyrant. Cf. Nietzsche’s famous expression, ‘be on your guard not to become the monster that you hunt!’).

Other sources of the legend are clear, such

as the Norse traditions of warriors dressing up in the skins of bears they had

killed. These warriors, termed berserkers,

were renowned for a superhuman strength and fierceness in battle that was

compared to trance or frenzy (hence the root of the word ‘berserk’). From this

it was easy to credit the warrior with the power of the beast he dressed up as.5

The follow up meaning came to represent a person mentally disturbed in such a

way that he believed he actually was the

beast. This latter usually goes by the designation ‘clinical lycanthropy’.

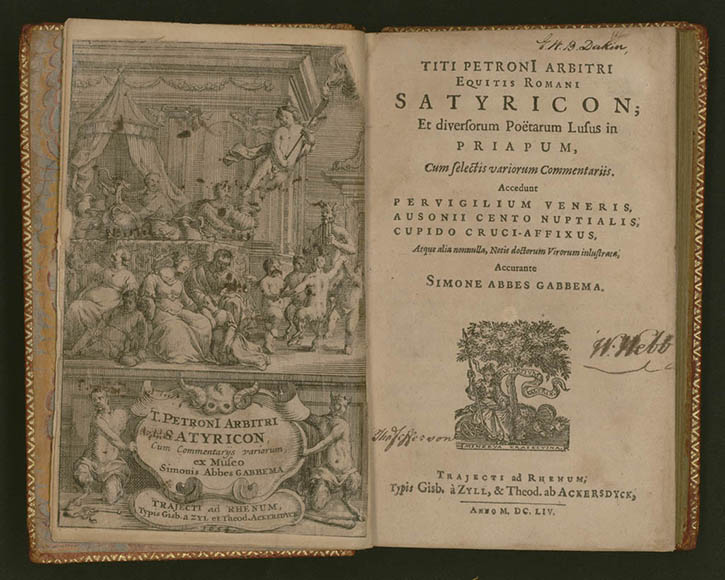

Some of the classic roots of the werewolf

legend can also be traced to the famed novel Satyricon, written by the Roman Gaius Petronius (27-66 C.E.), which was rendered into the equally famed Fellini’s Satyricon, a 1969 film by the

renowned Italian director Federico Fellini.6 Petronius’ Satyricon contains a chapter called The Feast of Trimalchio, centering on a

wealthy and pretentious former slave who entertains his guests with lavish

excess. During a particular feast he regales them with stories, one of which

involves him and a companion who go out one night on a walk that takes them

near a cemetery. While there, Trimalchio’s companion suddenly disrobes,

proceeds to urinate in a circle around them, turns into a wolf, and then runs

off into the woods, howling as he goes. Trimalchio finds that the man’s clothes

have turned to stone. He then visits his mistress who tells him that a wolf

just attacked their cattle, but was driven off with a pitchfork to the neck.

Come morning Trimalchio returns home, only to find his companion suffering a pitchfork

wound on his neck and being attended to by a doctor. He then concludes that the

man is a versipella (werewolf). Rossell

Hope Robbins noted that this story contains four essential elements of werewolf

legend: nocturnal transformation, nudity, urination and/or related specific magical

acts, and ‘sympathetic wounding’.7 The latter factor, the wounding

of a wolf and the later capture of a human with a similar wound, was actually

used as proof in European werewolf trials,8 the height of which

corresponded roughly to the peak of the witch-hunting craze in the 16th

century. (The fact that most witch-hunting took place in Germany and France, and that it was these two

countries that saw the most accusations and trials concerning alleged

werewolves as well, strengthens the likelihood that mass hysteria was at work).

The theme

of ‘sympathetic wounding’ was central in one of the more renowned werewolf

trials of that time, which occurred in the district of Poligny, France,

in 1521. The story begins with a traveler passing through Poligny who is

ambushed by a wolf. The traveler survives, trails the wolf, and ends up at a small

house where he discovers a wounded man who is being treated by his wife. The

traveler reports the wounded man—his name was Michel Verdung—to the

authorities, who arrest him.

Presumably

under torture Verdung told an elaborate story that implicated another man,

Pierre Bourgot. This man in turn made his own confession, which placed his ‘dealings

with the Devil’ originating nearly twenty years before, in 1502. Bourget

claimed that at that time, following a storm that had frightened off his sheep,

he was confronted by three ‘black horsemen’, one of whom offered to help him in

exchange for a vow of loyalty. Bourgot agreed, and to his relief his flock was

soon found. In a subsequent meeting one of the horsemen revealed himself to be

a disciple of the Devil, and extracted a further oath of obedience from Pierre,

who consecrated this oath by kissing the horseman’s left hand, which he

described as black and ice cold. After a couple of years Pierre began to lose his connection with the

Devil’s disciple and appeared to be re-associating with the Christian faith

again. Michel Verdung, another of the Devil’s servants, set to work luring Pierre back into the

satanic fold with promises of riches. Pierre

then attended a sabbat, during which he was made to apply an ointment of some

sort (a common theme in werewolf stories). Pierre then found himself turning into a

wolf; with the aid of Michel Verdung he was able to revert to his human form.

Confessions were extracted from Pierre Bourgot under torture. Amongst other

lurid actions he admitted to killing children, which including eating at least

two girls under the age of ten, and describing their taste as ‘delicious’. He

also claimed he fornicated with wolves. Bourgot, Verdung, and another

‘werewolf’, Philippe Mentot, were all tortured and then burned at the stake.9

Two more

sordid examples are illustrative of possible connections between some

lycanthropy cases and the modern designation ‘psychopathic serial killer’: those

of Gilles Garnier and Peter Stubb. The former was a hermit who was declared a

werewolf and executed in France

in 1574. He had been accused of murdering and eating children. He confessed

that he had been in the form of a wolf when he did these killings, and claimed

to have often dragged his victim away with his ‘fangs’. On one occasion Garnier

was caught with one of his victims by some peasants who later agreed that he

was in the shape of a wolf-man—body of a wolf, yet with his human face still

recognizable. Garnier was forced to confess to making a pact with the Devil,

convicted and burnt at the stake. (The actual story was that a wolf had killed

some local children, and Garnier, starving, was caught scavenging the carcass

of the child—which during that time easily became grounds for being accused of

something more sinister than scavenging).10 The latter story, concerning

the German Peter Stubb, occurred near Cologne in 1589; at the time, it was one

of the more famous werewolf trials in Europe. Stubb claimed to have a ‘magic

belt’ that enabled him to transform into a powerful and ravenous wolf. Similar

to Garnier he was accused of preying on women and young people, from as far

back as 1561. He further claimed that throughout his nearly three decades of raping

and killing he had been influenced by a ‘succubus’ (a female demon said to

visit men at night; the male counterpart is called an ‘incubus’). Stubb was

tortured in the harshest fashion, then decapitated, then burned. Colin Wilson

speculated that the cruelty of the torture may have resulted in fabricated

confessions, which doubtless was often the case with so-called witches and

lycanthropes.11 However it is also possible that this was an actual

case of a 16th century schizophrenic serial killer.

There were a number of other relatively

high profile trials involving alleged werewolves in Europe; most of these were

in the late 16th century, and most occurred in France. It’s unclear why there was

a concentration of cases at that time in that part of the world—apart from the

simple demographic fact that France was the most populated country in Europe

throughout the Middle Ages and into the early modern era—but it may have been

no more than the power of transmitted suggestion and mass-hysteria.

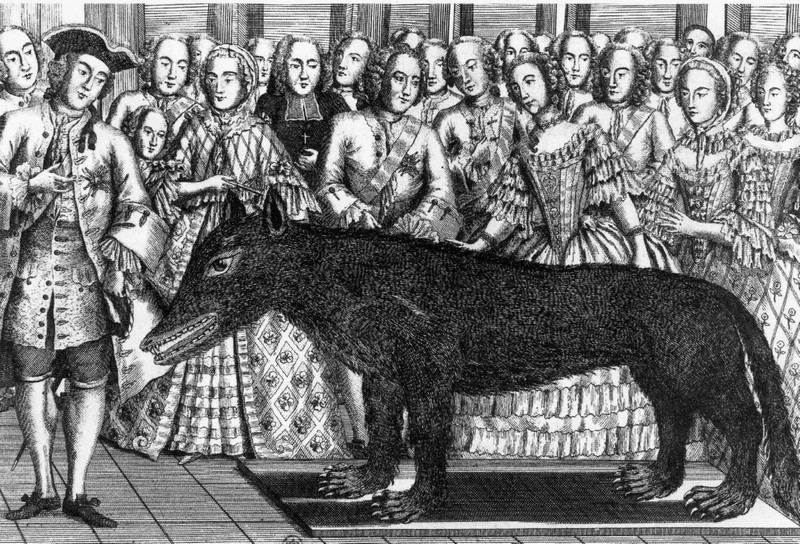

At any rate, one of the more infamous cases

occurred later, in the late 18th century, when werewolf cases had

become rarer (most witch-trials has stopped by then as well). It concerned the ‘Beast

of Gévaudan’, the name given for the alleged creature (or creatures) behind a

series of killings between 1764 and 1767 in south-central France in the former province of Gévaudan

(modern-day Lozère). Word about these killing traveled widely. The London

Magazine of January 1765 reported:

‘…a detachment of dragoons [light cavalry]

has been out six weeks after him. The province has offered a thousand crowns to

any persons that will kill him.’12

During this three year stretch, in a mountainous area ranging over two thousand square miles, some two hundred attacks were allegedly made, resulting in at least sixty-four deaths, and possibly over a hundred. The creature or creatures making these killings was never clearly determined; reports were made describing a vicious and foul-smelling beast that some thought resembled an African wildcat (lion, tiger, panther) or even a hyena. Reportedly it could leap to great heights, and had a large and deadly tail to accompany its lethal fangs.

A large wolf, initially thought to be the Beast of Gevaudan, that was shot and displayed at the court of Louis XV, in 1765

Most of the victims were children. The

matter came to the attention of King Louis XV, who commanded small armies to

track down the creature. Despite some two thousand wolves being shot, the army

failed to find the culprits. Eventually an elderly hunter named Francois

Antoine succeeded in killing a large animal that weighed 130 pounds and was

some 32 inches high at the shoulder (consistent with the dimensions of a large

male Gray wolf). This animal was identified by some surviving victims as the

culprit (it was subsequently stuffed and displayed for the king at Versailles). However, even

after this cull, killings of dozens of people, some of whom were children,

continued to be reported. Finally another hunter, 59 year old Jean Chastel,

succeeded in killing a creature in 1767. Upon opening its stomach, he

discovered human remains. Shortly after this, the killings stopped. This story

was rendered into a novel in 1936 by Abel Chevally (La Bete du Gévaudan), where it was embellished by adding the legend

that a pious and praying Charest killed the ‘evil beast’ with two silver

bullets (and hence the origin of the legend).13 Later speculation is that this ‘beast’ was a

wolf-dog hybrid, which can be larger and more aggressive than either of its

parents (and less likely to fear humans).14

The eccentric English scholar and Christian

fundamentalist Montague Summers, in his prodigiously researched work The Werewolf in Lore and Legend, wrote,

…belief

in the werewolf by its very antiquity and its universality affords accumulated

evidence that there is at least some extremely significant and vital element of

truth in this dateless tradition, however disguised and distorted it may have

become in later days by the fantasies and poetry of the epic sagas, roundel,

and romance.15

Summers’ motivation for uncovering this ‘vital element of truth’ may have been compromised by his Christian ‘Devil-hunting’ agenda, but there is a truth buried in his speculation, and indeed it lies at the basis of this study. The ‘disguised truth’ does not involve, however, anything as banal as actual men turning into berserk werewolves and committing atrocities under cold moonlight (although clearly, such atrocities occurred, regardless of their cause). The distorted practice detectable in werewolf legends that we are more interested in here concerns a bona-fide and ancient shamanistic tradition: shapeshifting.

Shapeshifting

‘Shapeshifting’ is a late 20th century term devised to describe ancient beliefs and practices found in most worldwide cultures. In its broadest sense it refers simply to the ability of a person to change their form, usually into the form of an animal, but it can also suggest a change into the form of any other entity, including human or imaginary creature.

Shapeshifting is a practice closely related

to ‘sympathetic’ or ‘imitative magic’. Probably the crudest form of this

practice is the common act, frequently engaged in by protesting groups or

crowds, of burning an effigy. In destroying the effigy it is believed that this

will bring some sort of ill fate to the likeness of the effigy. Certain

practices of what are sometimes categorized as black magic or sorcery are based

on this, with the stereotype of the magician or sorcerer who sticks pins into a

doll that represents an actual person. The more evolved form of this magic is

based on the idea that by mimicking something, we can become more deeply

attuned to it, and thereby understand it more fully, and, if desirable, even

gain some of its qualities.

We can also, provided we have the intent,

manipulate, control, or otherwise effect what we are imitating by first,

establishing a ‘resonance alignment’ with it, and second, changing our own

behavior in such a fashion that this change will cause the object of our focus

to change in a similar fashion. (This is similar to certain behavioral

practices called ‘mirroring’, something many good salespeople either know of,

or do naturally. If you adopt a person’s mannerisms in a sufficiently subtle

fashion, it can result in them feeling more relaxed and ‘in tune’ with you,

which in turn may cause them to be more agreeable to buying your product. This

is also similar to a psychotherapeutic tool called ‘reality pacing’, in which

the therapist achieves a strong rapport with their client by deeply

acknowledging their point of view, which in turn results in the client feeling

‘understood’, and in turn, more likely to be open to positive and constructive

use of the therapy).

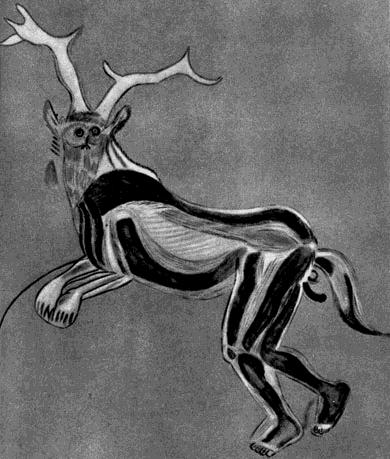

One of the oldest pieces of art work known,

the approximately 14,000 year old ‘Les Trois Freres’ cave paintings in southern

France, contains a particular rendering that has long been cause for deep

speculation. The image has come to be known as ‘The Sorcerer’ (shown on the right). It depicts what

appears to be a dancing man dressed up in a costume of sorts that seems to be a

composite of different animals. Alternately, is has been speculated that the

image shows a man who has partially transformed into an animal, or who himself

may simply be part animal.

The main idea behind a ‘shaman’—the modern

term for a practitioner of primordial magic—dancing as an animal, or otherwise

seeking to attune deeply to the spirit of an animal, is mainly so that the

shaman can acquire some of its natural powers. These ‘natural powers’ can be

understood in terms of subtle, psychological or spiritual aspects—the courage

of a lion, the perspective of a hawk, the grandness of an eagle, the power of a

tiger or bear, the gentleness of a deer, the cunning of a fox, and so on. They can also be seen in

terms of simple physical qualities—physical power, strength, endurance, health, etc. In many worldwide shamanistic traditions, it is believed that the

act of deliberately attuning to the spirit of a particular animal is to

‘acquire’ a guardian spirit (or sometimes called a ‘totem’ or ‘power animal’)

based on the energies of the entire species represented by the animal. In other

words, to acquire an eagle power animal is to tap into the collective power of

Eagle; to acquire a bear power animal is to receive the help of Bear, and so

on.

The technical term for shapeshifting is

therianthropy (from the Greek therion,

‘wild beast’, and anthropos,

‘human’). The term ‘shapeshifting’ is somewhat misleading, as the vast majority

of shamanistic traditions dealing with this matter eventually acknowledge that

so-called shapeshifting is in fact an altered state of consciousness, and thus

is a transformation of perception,

not physical form. (Which, in the shamanistic context, does not diminish the

value and purpose of it).

That said, the difference between ‘shift in

perception’ and ‘shift in form’ was doubtless rarely understood and even now is

not always openly clarified, no doubt in large part due to the common folk of

past times believing in the physical reality of therianthropes of whatever

sort. The anthropologist Michael Harner, in his popular work The Way of the Shaman (1982), reported

how the belief in shapeshifting is widespread in shamanistic traditions the

world over.16 He mentions the pervasiveness of the belief in North,

Central and South American Indian mythology, amongst Australian aborigines,

Scandinavian Lapp (where werewolfery is especially prevalent), Siberians and the

Inuit, throughout Africa, and so on.

Harner’s popularization of the shamanic traditions came closely on the heels of Carlos Castaneda’s famous (or infamous, take your pick) and highly influential books describing his alleged apprenticeship to a Yaqui Indian shaman named ‘don Juan Matus’. (He ended up publishing twelve books, but the first three—The Teachings of Don Juan, A Separate Reality, and Journey to Ixtlan, all brought out between 1968 and 1972, remain his most famous). In some of his books Castaneda described his own ‘transformation’ into a crow. In particular Castaneda went a long way toward conveying the importance of perception in experience, and of the meaning and purpose of altered states of consciousness. As a trained anthropologist and a fine writer, Castaneda’s works made for compelling reading. He was more or less ‘outed’ in the late 1970s by scholar Richard DeMille, who demonstrated almost irrefutably that Castaneda had fabricated most, if not all, of his story. Nevertheless as Harner and others have shown, Castaneda was drawing the substance of his ideas from legitimate sources. He had a gift for ‘bringing to life’ shamanistic ideas that previously had been the province of dry academic texts.

Both Harner and Castaneda were preceded by the

Romanian scholar Mircea Eliade, who in 1951 put out his landmark work Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy.

This work went a long way toward shedding light on a key matter related to

shapeshifting, and that is the question of the so-called ‘familiar’ or ‘helping

spirit’. The word ‘familiar’ relates to family-intimacy; in late 16th

century Europe (more or less the peak period

of both witch and werewolf trials) the word also came to be used to represent

the ‘evil helping spirit’ of a witch or sorcerer. The historian James Sharpe

noted,

…the

idea that a witch was usually assisted by a familiar in the shape of an animal

constantly recurred in pamphlet accounts; indeed it was present in two of the

first surviving pamphlets concerned with witchcraft, both published in 1566…17

It’s ironic to note that the more astute

scholars of that time held a view that discounted the possibility of actual

shapeshifting, seeing it all rather as illusion or perceptual tricks—and yet at

the same time, ascribed a supernatural

cause to these illusions—namely, that they were the work of the Devil. In

1608 the Italian clergyman Francesco Guazzo published his Compendium Maleficarum (a ‘study’ of witches), in which he wrote,

…As I

have already said, no one must let himself think that a man can really be

changed into a beast, or a beast into a real man; for these are magic portents

and illusions…for the Devil, as I have said elsewhere, deceived our senses in

various ways. Sometimes he substitutes another body, while the witches

themselves are absent…and himself assumes the body of a wolf formed from the

air and wrapped around him, and does those actions which men think are done by

the wretched absent witch who is asleep.18

Werewolfery was impossible, and thus an

illusion: but an illusion created by the Devil. It was a twisted synthesis of

critical thinking and religious dogma.

Lurid and even erotic powers were ascribed

to some ‘familiar’ spirits, such as the bizarre practice of sucking blood from

the genitalia or the anus of the witch.19 This was all seen as a

variant of the belief, prevalent on continental Europe of that time, that

insisted that the Devil had wild orgies with witches during late night

ceremonies called ‘sabbats’. However as legitimate

shamanistic traditions bear out, the ‘familiar’ or ‘helping spirit’ is not seen

as lascivious, let alone evil; on the contrary, it is generally regarded as a

benevolent assistant, loyal, trustworthy, and able to instill helpful power

into the shaman who invokes it.

Eliade defined three essential categories

of ‘spirits’ within the shaman’s world: ‘familiars’ or ‘helping spirits’;

‘tutelary spirits’; and ‘divine or semi-divine beings’.20 It is the

first group, the ‘helping spirits’, which is of interest in the matter of

shapeshifting. Another late 20th century term that has become popular

for this class of totem entity is ‘power-animal’.

A common theme in shamanic tradition is

that of the shaman undergoing a key process of awakening (or ‘illumination’),

after which he must retreat to a wild and natural setting and obtain a helping

spirit. This usually occurs via the shaman entering some sort of trance or

altered state of consciousness (as via dance, drumming, meditation,

hallucinogens, etc.). When the ‘helping spirit’ comes to him he enters into a

deep communion with it, to the point of taking on some of its behavior and

characteristics:

The spirits all manifest themselves through the shaman, making strange noises, unintelligible sounds, etc.21

The helping spirit is almost always the

spirit-form of a particular animal. Eliade clarified that this process is not

the same as ‘possession’, in that the shaman is acting willfully and

voluntarily—and that if anything, the process is reversed, in that it is the

shaman who is taking possession of the helping spirit. The helping spirit is of

great importance to the shaman, as it represents the shaman’s ability to

navigate the ‘bridge’ between the physical dimension and the ‘other worlds’.

Many worldwide traditions feature legends of the ‘psychopomp’, the term for a

spirit-guide who ushers the soul of a dead person to and through the Other Side,

or even to become the new form of the deceased person.22 Commonly

this spirit-guide is in the form of an animal (for e.g., the Egyptian jackal-god

or wild dog-god Anubis).

The ‘tutelary spirit’ is generally

understood to be a guardian spirit of a very high order, and in some respects

correlates to the idea of the ‘Holy Guardian Angel’ that is central to many

mystical schools of the Western esoteric tradition. This spirit is, in fact,

the higher self of the person, but seen from the perspective of the personality

it appears to be a distinct entity that ‘guards’ or ‘oversees’ the person’s

life. In describing beliefs among shamans of Siberia and Mongolia, Eliade writes,

The tutelary animal of the Buryat shamans is called the khubilgan, a term that can be interpreted as ‘metamorphosis’ (from khubilkhu, ‘to change oneself’, ‘to take on another form’). In other words, the tutelary animal not only enables the shaman to transform himself; it is in a manner his ‘double’, his alter ego. This alter ego is one of the shaman’s ‘souls’, the ‘life soul’.23

As Eliade astutely noted, the whole basis of the shaman’s connection to the helping spirit relates to not just his ability to travel ‘between worlds’, but also to his ability to undergo ‘death and resurrection’ by overcoming the limitations of material existence. In short, the ability to shapeshift ultimately relates to the ability to conquer death by undergoing an initiation that thematically involves death itself. Not the death of simply the body, but the death of what we can call egocentric delusions brought about by attachment to material form.

The

Psychology of Familiars and Shapeshifting

To further increase our perspective on all

this, it’s helpful to discuss briefly the psychology of shapeshifting. Before

doing so it should be clarified, however, that the traditional shaman is a metaphysical

realist, in the sense of believing that the various dimensions and entities

contacted actually exist outside of his or her own mind.24 Any

attempts at psychological interpretation in the matter of shamanic practices

needs to be tempered with this understanding. That doesn’t have to stop us, however,

from looking at the big picture. Whether we regard something as ‘outside’ of

our consciousness or not, we still have to come to terms with the lesson that

the experience represents for us if we wish to understand ourselves better. This is true for any wishing to understand the underlying psychology of certain shamanistic practices.

First, to look at the obvious: the question of mental illness. As mentioned above in the discussions of some of the actual werewolf trials of Renaissance Europe, the cases that involved murders and other criminal depravities (as opposed to ‘confessions’ fabricated under pain of torture) were quite clearly examples of what today would be called psychopathy. There is however a ‘milder’ form of mental illness connected to mystical experiences, what the psychiatrist Roger Walsh called ‘mystical experiences with psychotic features’. Walsh cited transpersonal psychologists Stanislav and Christina Grof who noted in their studying the cases of ‘ordinary’ people who underwent spiritual crises that their mystical experiences often involved themes such as great suffering (breakdown of some sort) and symbolic death, followed by ‘rebirth’, ‘ascent and magical flight’, and even ‘communication with animals or animal spirits’.

Walsh goes on to discuss a shamanic phenomenon of particular relevance to a chapter on werewolves, that being ‘possession’:

Experiences of possession have been described throughout history and may be a major feature of the shamanic crisis. Today they may occur either spontaneously or in religious or psychotherapeutic settings. The experiences battling with or being overwhelmed by rage and hatred can be of hideous intensity. So powerful, repugnant, and alien do these emotions feel that they seem literally demonic, and the victim may fear he is engaged in a desperate battle for his very life and sanity.25

He goes on to point out, however, that the

entire matter can be understood as a process of shedding an old self-image, i.e.,

a type of spiritual metamorphosis:

Psychiatrist

John Perry has described the renewal process as an experience of profound,

all-encompassing destruction followed by regeneration…yet this destruction is

not the end but rather is a prelude to rebirth and regeneration.26

The ‘degraded’ form of this process of

shamanic death, regeneration, and rebirth is well symbolized by the dark,

blindly destructive face of the werewolf—the end result of a tormented

transformation into a powerful beast (in effect, possession), under moonlight. For

the werewolf, the ‘rebirth’ never comes. There are only endless deaths (losing

consciousness) and transformations which he has no ability to control. (The

German novelist Herman Hesse, in his 1927 novel Steppenwolf, about a man inwardly conflicted over the tug-of-war

between his ‘high, spiritual’ side and his ‘low, animalistic’ side, described

the process more in terms of social alienation, rejection of bourgeois values

and mainstream mediocrity. This is an

example of what Colin Wilson called an ‘Outsider’, one who instinctively seeks

to move beyond the mediocrity of the masses, but in most cases lack the

guidance, or the ability to ‘regenerate’ and re-invent themselves in a

fulfilling manner).

True shamanic practice involves voluntary

intent in the matter of regeneration and rebirth. From the point of view of a

person seeking (consciously or not) to become inwardly unified, integrated, a

whole person, the ultimate spiritual purpose of associating with ‘familiars’ or

the practice of shapeshifting is becoming more conscious of elements of one’s

own nature. The key, of course, is consciousness. We cannot integrate a part of

our nature without first becoming aware of it. We cannot integrate our ‘inner

beast’ and all the ways its energies become manifest, without first seeing and

understanding something of the nature of this beast.

In referring to the tale of the wizard

Faust and the devil he conjures (Mephistopheles), C.G. Jung wrote,

Mephistopheles

is the diabolical aspect of every psychic function that has broken loose from

the hierarchy of the total psyche and now enjoys independence and absolute

power. But this can be perceived only when the function becomes a separate

entity and is objectivated or personified…’27

Magical evocation—the classical practice of

a wizard or magician standing in a circle fortified by Holy Names and ‘raising

a spirit’ by calling it forth via various magical formulae—is essentially the

ritualized equivalent of the shaman acquiring a helping spirit. (It goes

without saying that the ‘type’ of spirit being raised, its disposition and

qualities, can vary greatly). Seen from a psychological perspective, this

represents ‘calling forth’ elements of the magician’s psyche so that he can

objectify them and begin to understand them. (In alchemy, this stage

corresponds to necessary processes defined by various forms of separation,

prior to recombining them). ‘Understanding them’ does not, of course, mean that

the magician or shaman automatically understands how the ‘spirit’ ultimately reflects

a quality or potential within the magician or shaman’s own psyche. This point

is crucial. Things are degraded when they are disconnected, disintegrated,

spread out and scattered. The risk in ‘evoking’ parts of our nature to

objective reality is that we may be so disturbed by what we see that we disown

these parts, or worse, project them on to others, who then become our

convenient scapegoats.

The psycho-spiritual purpose of shapeshifting can be only one: to objectify parts of our nature, establish a relationship with them, and ‘re-absorb’ them by owning and taking responsibility for their energies—which are, after all, our energies. In so doing we integrate their qualities. In so doing, we become more Whole.

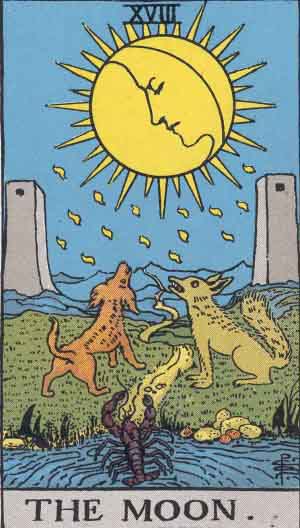

The ‘wolfman’ is part of human nature—aggressive

impulse, secretive and repressed, potentially destructive—for whatever causes.

It has been commonly associated with masculine impulse, but it is alive and

well in the feminine mind also, hinted at in its legendary connection with the

lunar cycle, and further shown in the traditional Moon card of the Tarot, which

commonly features a dog howling at the Moon. Man or woman, we need not undergo

a writhing and tormented transformation into a murderous beast under a full

Moon—that is, we need not deny and repress our aggressive impulses, by becoming

secretive or furtive about them. As Jung wrote,

…we

have to expose ourselves to the animal impulses of the unconscious without

identifying with them and without ‘running away’; for flight from the unconscious

would defeat the purpose of the whole proceeding. We must hold our ground,

which means here that the process initiated by…self-observation must be

experienced in all its ramifications and then articulated with consciousness to

the best of understanding.28

Finally, it bears mentioning that a term

from alchemy—antimony (an actual chemical element with the atomic number of 51)—referred

to the hidden wild beast within, and was associated with the wolf in medieval

texts. It particularly pointed toward the shadow element of the monk or priest,

something that has become all too much a matter of common knowledge.

Deity

Yoga and the Assumption of God-forms

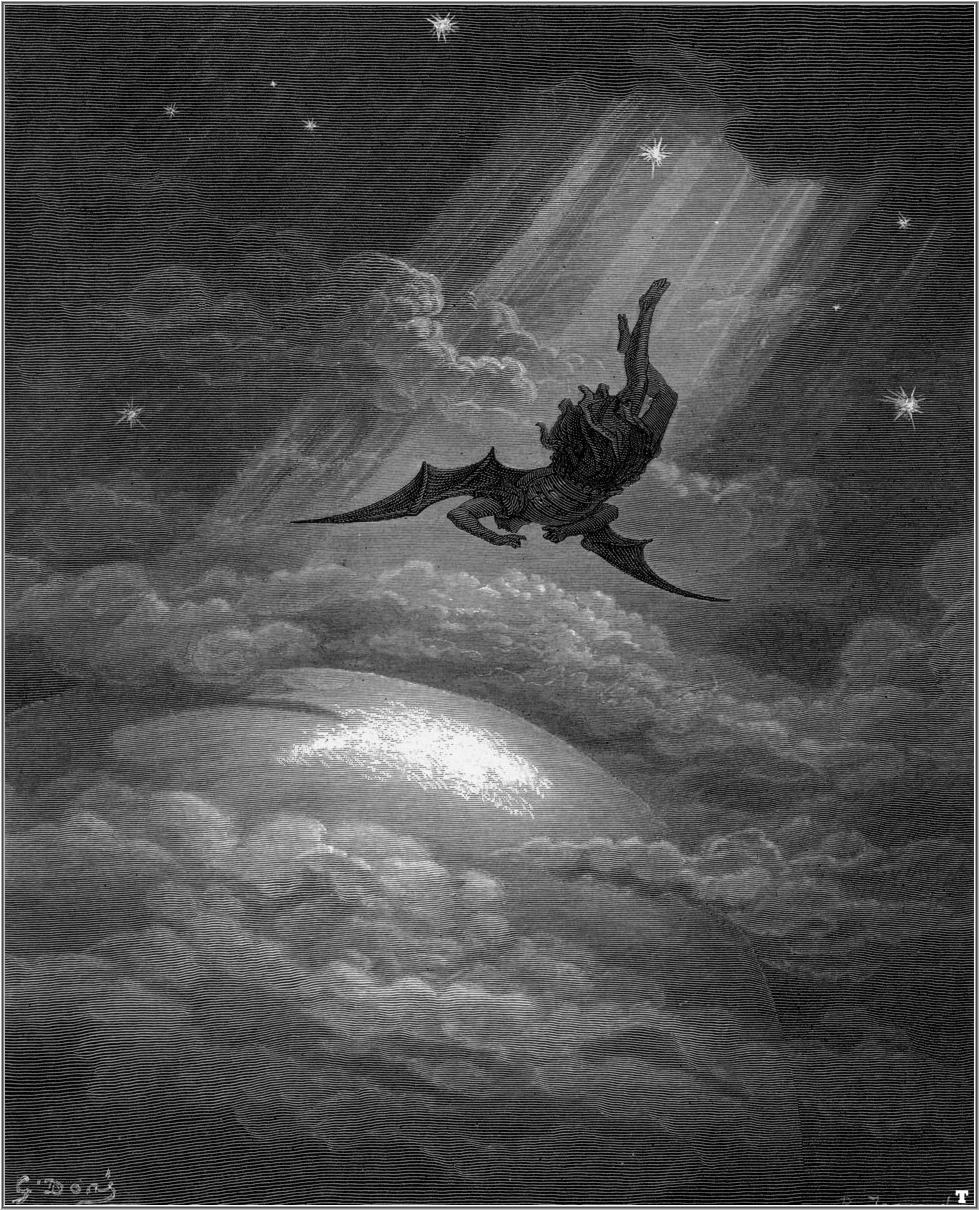

If the brutal and twisted imagery of the

werewolf—secretive, cursed, predatory, preying mostly on women and children,

the ghoul of every Little Red Riding Hood’s worst nightmare—represents some of the

more degraded elements of imagination, then the esoteric practices known as the

‘assumption of god-forms’ and ‘deity yoga’ represent some of its most elevated.

As indicated above, in psychological language the werewolf is

simply a part of the ‘Shadow’. As with all Shadow-work, the aim is not to run

away from this energy, nor to indulge it, but rather to courageously face into

it, embrace it, and transmute its powerful energies. In so doing, the vitality,

creativity, and power of the Shadow are freed up, minus the secretiveness,

hostility and aggression. Much as with a powerful ‘problem child’, we need to

establish a profound level of relationship with this energy and ultimately take

responsibility for the reality that it is not our ‘feral child’, it is rather part of us.

Tibetan Buddhism, being a unique amalgam of

rarefied Indian Buddhist metaphysics and earthy Tibetan shamanism, developed

particular methods for working with and transforming some of the darkest and

densest energies of the Shadow. Some of these practices are included in parts

of what is usually termed ‘deity-yoga’, and they involve utilizing particular

tutelary deities as yidams (the

Sanskrit equivalent term is Ishta-deva,

meaning ‘deity that is desired and given reverence to’). A yidam is a celestial being that is the object of personal focus and

devotion, either for a spiritual retreat, or as a life-long object of

meditation.

In the Tibetan Buddhist pantheon, many

exalted deities are recognized, but three very important ones are Chenrezig

(the lord of Compassion, known in India

as Avalokiteshvara and in China

as Kuan Yin); Manjushri, lord of Wisdom; and Vajrapani, lord of Power. These

deities in turn all have a ‘wrathful aspect’—for Chenrezig, Mahakala; for

Manjushri, Yamantaka; and the wrathful face of Vajrapani (which usually goes by

the same name). These ‘wrathful deities’ all appear, to one unaware of Tibetan

Buddhist teachings, as simply demonic—fierce, ugly, threatening, often adorned

with skulls and of a terrifying disposition. But the three just mentioned are

not demons; they are expressions of ‘active wisdom’, ‘active compassion’, and

‘active power’, respectively. According to the teachings they exist in part to

protect the dharma (Buddhist teachings), and any practitioner who calls on

them, a Protector/Guide theme that is found in many worldwide spiritual mythologies.

But there is a subtler, deeper teaching involved here, and it has to do with the

‘taming’ and integration of Shadow-energies. The fierce deities of Tibetan

Buddhism can be thought of as masters of ‘tough love’, fearless and courageous,

spiritual warriors ready to deal with the darkest faces of our egos. They do

this not by beating these parts of our nature into submission, but rather by

resonating with them, entering their worlds, speaking their language, so to

speak, so as to acquire their trust. In so doing, they are then capable of

guiding these parts of our darker nature back into the light of integrated

awareness.

In referring to Yamantaka, the wrathful aspect of Manjushri (lord of Wisdom), Buddhist psychologist Rob Preece wrote,

Yamantaka

gives the forces of the Shadow a symbol that hooks their energy and provides a

channel and direction for their expression and transformation…he is able to

harness their energy and embody their power consciously. The archetypal forces

of the instincts and emotions held in the Shadow are given a channel through

Yamantaka so that they can be brought into consciousness, transformed, and

integrated…as the Shadow forces are transformed, their energy is not lost, but

integrated into personal power.29

Preece also cited the vivid analogy of a gang

of biker thugs gone out of control (representing our Shadow-elements that are

disconnected and ‘acting out’, such as impulsive anger, tendencies toward

depression, unhinged jealousy, etc.). He then asks how such thugs should

correctly be ‘put in their place’, and suggests that it will not be effectively

done by a mild-mannered sort, but most likely by one who resembled a

biker-tough guy himself, and yet is really an advanced teacher and evolved

being. That is what a wrathful deity like Yamantaka represents: the highest

expression of tough love.

However, the deeper point is to understand that the wrathful deities are not actually separate from us. They are elements of our own nature. The difference between them and a tormented creature like a werewolf is that they are using their power and aggression in the service of a higher purpose. The werewolf is the beast with no purpose, no reason for being; a furtive expression of repressed and distorted passion. When purpose is squashed, when there exists no other reason for being than serving someone else’s agenda, then hostility breeds, and seeks outlets.

The fundamental motivating force toward a

higher purpose is compassion, precisely because ‘higher purpose’ always,

without fail, involves playing a role in the awakening and evolution of the

human being. Accordingly, this compassion is cultivated with a view toward

helping others develop and awaken to their true nature as beings of unlimited

potential. And the key quality in this compassion is enthusiasm. The English word ‘enthusiasm’ derives from the Greek

terms enthousiasmos and entheos, both of which relate to ‘divine

inspiration’ and the idea of being ecstatically possessed by a divine being.

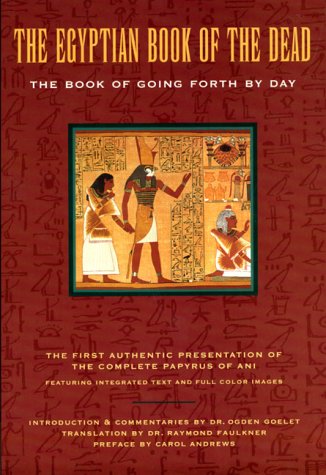

The idea of merging with a divine being is

ancient, and found within many world myths and wisdom traditions. It is very

common in ancient Egyptian tradition but perhaps in ways that have not always

been correctly interpreted, an idea that was developed by Jeremy Naydler in his

seminal work Shamanic Wisdom in the Pyramid

Texts.30 Naydler argued that ancient Egyptian writings preserved

in the famous Pyramid texts are more than simple funerary arrangements or

frivolous mythology, but are rather teachings describing the initiatic process

of awakening to the divine on Earth, while alive, and not just in some

after-life. Naydler wrote:

The

role of the shaman as mediator between the ‘nonordinary’ reality of the spirit

world and the ordinary reality of the sense-perceptible world is in many

respects paralleled in ancient Egypt

by the Egyptian king, whose role is similarly to act as mediator between

worlds. Such important shamanic themes as the initiatory death and

dismemberment followed by rebirth and renewal, the transformation of the shaman

into a power animal, the ecstatic ascent to the sky, and the crossing of the

threshold of death in order to commune with ancestors and gods are all to be

found in the Pyramid Texts…31

The Western esoteric practice known usually

as ‘the assumption of Godforms’ involves extensive usage of imagination. This

is done via the practice of visualizing in detail the particular god (usually

Egyptian) chosen to unify with. As esoteric scholar Arthur Versluis wrote, in

referring to ancient Egyptian practices of identifying with particular deities,

…to

be the God, to not only mirror, but to attain complete identification with the

God, with that state of consciousness, was the aim of initiatory ritual as such.32

The result is intended to change or

transmute the seeker’s ‘Body of Light’ (recall our discussion of this in the

chapter on Frankenstein) into the ‘Body of God’. That is the ageless goal of

mysticism and high magic: union with the Source.

The Western esoteric practices of assuming

Godforms are, of course, very similar to the Tibetan Buddhist practices of

deity yoga mentioned above, although it should be pointed out that the Tibetan

systems generally emphasize the necessity of developing compassion and

understanding emptiness (the intrinsic formlessness of ultimate reality) prior

to engaging the visualization work. There are also preliminary trainings in

Western esoterica, but they relate more to the development of will and

imagination rather than compassion and grasp of emptiness. Both approaches,

however, are ultimately concerned with the highest possible usage of

imagination, as a tool to realize our divine potential.

As a closing point of consideration: the wolf as a symbol has been linked to ‘type six’ in the nine-point system of personality types known as the ‘Enneagram’. This personality-type system is very complex and can only be mentioned in passing here. But of note is that ‘Type Six’ in the Enneagram system is commonly associated with a fear-driven personality that has a very conflicted relationship with authority and power. Helen Palmer called the type ‘the Devil’s Advocate’, a reference to its anti-authoritarianism, which is one way of dealing with fear of power. (The other way is to acquire a ‘protector’ of some sort).33 Claudio Naranjo called the ‘Type Six’ the ‘persecuted persecutor’, and described its more negative face as a cowardly recoil from life, a tendency to blame oneself rather than appropriately challenge outer obstacles, and to exercise excessive obedience to authority, or feigned friendliness, as a means of managing one’s anxiety.34 That is one way to deal with fear (the passive face of Type Six). The other way is to attack in a subversive fashion, ‘behind the scenes’ and ‘under the cover of night’, so to speak, and that sums up the demeanor of the werewolf.

The transformation of this matter lies in

healthy empowerment, and that is where ‘tutelary deities’ like Yamantaka and

Vajrapani carry appropriate symbolism, representing as they do a fearless

embrace of life and the transmutation of fear-energy into vitality, aliveness,

passion, and purposeful direction in life.

Notes

1. This story is complex and ultimately

involves decidedly less arcane issues such as inter-tribal rivalries,

resistance to British rule, and the usual matters of corruption in an unstable

society following the turmoil of the Second World War. See David Pratten’s The Man-Leopard Murders: History and Society

in Colonial Nigeria (Indian University Press, 2007).

2. Gordon Wellesley, Sex and the Occult (London: Souvenir Press, 1973), pp. 66-67.

3. This idea was explored as far back as

1865, by the clergyman/scholar Sabine Baring-Gould, in his intelligent and

comprehensive study The Book of Were

Wolves.

4. Barry Holstun Lopez, Of Wolves and Men (London: J.M. Dent and Sons Limited), 1978, p.

231.

5. Rossell Hope Robbins, The Encyclopedia of Witchcraft and Demonology (New York, Crown Publishers), 1959, p. 325.

6. Fellini

underwent Jungian analysis and in part credited Jung’s ideas on archetypes and

the anima/animus as influential on his film.

7. Ibid, p. 325.

8. Lopez,

Of Wolves and Men, p. 234.

9.

Robbins, The Encyclopedia of Witchcraft

and Demonology, p. 537.

10.

Lopez, Of Wolves and Men, pp.

240-241.

11. Colin

Wilson, The Occult (New York: Vintage

Books, 1973), p. 440.

12. Montague Summers, The Werewolf

in Lore and Legend (Mineola: Dover

Publications, 2003), p. 235. Originally published in 1933 as The Werewolf.

13. Robert Jackson,

Witchcraft and the Occult (Devizes, Quintet Publishing, 1995)

p. 25.

14. Lopez, Of Wolves and Men, pp. 70-71.

15. Summers, The Werewolf in Lore and Legend, p. 1.

16. Michael Harner, The Way of the Shaman (New York: Bantam Books, 1982), pp. 73-83.

17. James Sharpe, Instruments of Darkness: Witchcraft in England 1550-1750 (London: Penguin Books, 1997), p. 71.

18. Francesco Maria Guazzo, Compendium Maleficarum (New York: Dover Publications, 1988), p. 51. Guazzo drew some of his material from the notorious witch-hunter Nicholas Remy.

19. Sharpe, Instruments of Darkness, pp.73-74.

20. Mircea Eliade, Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy (Princeton University Press, 1974; originally published in French in 1951), p. 88.

21. Eliade citing Webster, Ibid, p. 92.

22. Ibid, p. 93.

23. Ibid, pp. 94-95.

24. Roger Walsh, The Spirit of Shamanism (Los Angeles: Jeremy P. Tarcher Inc., 1990), p. 115.

25. Ibid, p. 95.

26. Ibid, p. 95.

27. C.G. Jung, Psychology and Alchemy (Princeton University Press, Bollingen Series, 1980), p.69.

28. Ibid, pp. 145-146.

29. Rob Preece, The Psychology of Buddhist Tantra (Ithaca: Snow Lion Publications, 2006), p. 187.

30. Jeremy Naydler, Shamanic Wisdom in the Pyramid Texts: The Mystical Tradition of Ancient Egypt (Rochester: Inner Directions, 2005).

31. Ibid, p. 15.

32. Arthur Versluis, The Egyptian Mysteries (London: Arkana, 1988), pp. 117-118.

33. Helen Palmer, The Enneagram (New York: HarperCollins, 1991), p. 237.

34. Claudio Naranjo, Ennea-Type Structures (Nevada City: Gateways/IDHHB Inc., 1990), pp. 97-110.

Copyright 2011, by P.T. Mistlberger, all rights reserved.

__________________________________

by P.T. Mistlberger

It was on a dreary night of November that I beheld the accomplishment of my toils. With an anxiety that almost amounted to agony, I collected the instruments of life around me, that I might infuse a spark of being into the lifeless thing that lay at my feet.

—Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein

In some respects, Frankenstein, originating in Mary Shelley’s classic early 19th

century novel, is the prototype of both the modern horror creature and modern

stories of the supernatural. As a film,

it represented as best as any the warping, cloaking, and sensationalizing of

legitimate and important ideas from the mystical and occult traditions.

In some respects, Frankenstein, originating in Mary Shelley’s classic early 19th

century novel, is the prototype of both the modern horror creature and modern

stories of the supernatural. As a film,

it represented as best as any the warping, cloaking, and sensationalizing of

legitimate and important ideas from the mystical and occult traditions.The story is unique in how its title, a name which refers to a fictional Swiss scientist (Victor Frankenstein) who creates a creature that he loses control of, long ago came to be confused with the creature itself. This creature is no ordinary creature, but in fact a terrible monster, and one that has inhabited the imagination of many a child influenced by ‘monster stories’ and has made for many a Halloween-party costume. The first film version of the story appeared in 1910, with Charles Ogle playing the monster. It was made by the Edison Company, owned by Thomas Edison, the seminal scientist and businessman whose genius was behind the development of both the light bulb and the motion picture camera—a perhaps fitting link with the science-fiction theme of inspired yet mad creation behind Shelley’s monster. The more iconic Frankenstein film appeared in 1931, starring Boris Karloff (1887-1969) as the monster. (Despite his Russian-sounding name Karloff was actually an Englishman; his birth name was William Pratt). It is from the 1931 film that the stereotypical look of Frankenstein’s monster was first created. Since then some forty movies have been shot featuring Frankenstein’s monster. The classic Frankenstein’s monster look was even mimicked in the T.V. comedy show The Munsters (1964-66) by the character Herman Munster (played by Fred Gwynne).

Origins

Frankenstein:

or, The Modern Prometheus—viewed by many as the

most influential modern fictionalized treatment of the occult—was the creation

of a teenage girl. It was written by English novelist Mary Shelley (nee Godwin,

1797-1851). She began the novel in mid-1816 at age eighteen and finished it a

year later. (This is more impressive than it may sound: between 1816-17 she

gave birth to two children, got married, and lost her half-sister to suicide).

It was first published in 1818 when she had not yet turned twenty-one; this

first edition was brought out anonymously. Her husband, the renowned poet Percy

Bysshe Shelley, encouraged her writing and wrote the Preface. Mary Shelley was

credited as author only in the second edition which was brought out in 1823.1

A further revised edition was published in 1831, in which some of the

language in the first part of the story was toned down.2

Frankenstein:

or, The Modern Prometheus—viewed by many as the

most influential modern fictionalized treatment of the occult—was the creation

of a teenage girl. It was written by English novelist Mary Shelley (nee Godwin,

1797-1851). She began the novel in mid-1816 at age eighteen and finished it a

year later. (This is more impressive than it may sound: between 1816-17 she

gave birth to two children, got married, and lost her half-sister to suicide).

It was first published in 1818 when she had not yet turned twenty-one; this

first edition was brought out anonymously. Her husband, the renowned poet Percy

Bysshe Shelley, encouraged her writing and wrote the Preface. Mary Shelley was

credited as author only in the second edition which was brought out in 1823.1

A further revised edition was published in 1831, in which some of the

language in the first part of the story was toned down.2

The origin of the story lies in a series of meetings between Shelley, her husband Percy, the Romantic poet Lord Byron, and two others. The group had been reading and discussing German ghost stories in French translations, when Byron proposed that they all attempt to create their own ghost story. Mary Shelley initially experienced a block in her imagination and for several days was unable to come up with anything. One night she listened to her husband and Byron discuss the possibilities of galvanism and related matters. (Galvanism, a term coined in the late 18th century, referred to the idea of stimulating muscles via applying an electric current to them, and to the possibility of animating dead tissue via electricity. The word was taken from the discoverer of bioelectricity, Luigi Galvani, who in 1791 first published his study showing how nerve cell signals passed to muscles are electrical in nature. The modern term, electrophysiology, is the study of the electrical properties of living cells). Shortly after, Shelley conceived of her idea of the story of a scientist who constructs a living creature from derelict organic parts. The outline of the story came to her in a series of visions while she lay in bed unable to sleep, having fallen into a light trance state.

The novel is a classic of 19th century horror. Some have even attempt to portray it as the first science-fiction novel, although in fact the book barely qualifies as science-fiction, as there is no real attempt at ‘science’ anywhere in its text, even the ‘techno-babble’ science typical of the genre; it rather leaps straight to the end result, the creation of the monster, thereafter being one extended commentary on the results of such a creation. The subtitle of the book, or, The Modern Prometheus, refers to the Greek god (one of the Titans) who brought fire to humanity by stealing it from Olympus, an act for which he was severely punished by Zeus. The early 20th century occultist and artist, Austin Osman Spare, once defined magic as the art of ‘stealing fire from heaven’, a reference to the Prometheus myth.3

Shelley did not originally set out to write Frankenstein with any serious intention to express esoteric ideas; she simply wanted to write a good horror story. In her Introduction to the revised 1931 edition, she admitted, following her meetings with Percy Shelley and Lord Byron,

I busied myself to think of a story—a story to rival those which had excited us to this task. One which would speak of the mysterious fears of our nature and awaken thrilling horror—one to make the reader dread to look around, to curdle the blood, and quicken the beatings of the heart. If I did not accomplish these things, my ghost story would be unworthy of its name.4

Her husband added that the entire brain-storming sessions that led to his wife conceiving Frankenstein were conducted in the spirit of playfulness:

…We crowded around a blazing wood fire and occasionally amused ourselves with some German stories of ghosts which happened to fall into our hands. These tales excited in us the playful desire of imitation.5

Notwithstanding the spirit of its origins, the novel, despite a mixed critical reception, was an immediate bestseller and grew to have lasting iconic influence. In addition and more importantly to our concerns here, the connection between Frankenstein as penned by Shelley, and the Western esoteric tradition, is clear. Shelley has the protagonist of her novel, Dr. Frankenstein, studying such major occult luminaries as Albertus Magnus, Agrippa, and Paracelsus. When Frankenstein sets about achieving his great creation (and ultimately, monster), he utilizes both science (chemistry) and alchemy. Shelley took this from Paracelsus’ actual attempts to create an artificial man (see below).

That said, the general attitude of the book, as expressed by Victor Frankenstein, is progressive, and Shelley was very aware of the movement from mystical alchemy to practical chemistry. In the novel, young Victor discovered Agrippa’s occult writings as a boy, and excitedly reported them to his father, who disapproved, remarking,

‘Ah! Cornelius Agrippa! My dear Victor, do not waste your time upon this; it is sad trash’.6

Victor was unimpressed with his father’s lazy and disdainful attitude, however, and he continued to study Agrippa, as well as Paracelsus and Magnus.

I read and studied the wild fancies of these writers with delight; they appeared to me treasures known to few besides myself.7

But this thrill was not to last. Soon after young Victor witnessed an oak tree being destroyed by a lightening bolt. It just so happened that a man ‘of great research in natural philosophy’ was with him at the time, and he proceeded to explain to Victor some basics of electricity and galvanism. Victor was so impressed that for him, Agrippa and the occultists and alchemists and other ‘lords of my imagination’ were overthrown.8 He then determined to devote himself passionately to the study of ‘that science as being built upon secure foundations, and so worthy of my considerations’.9 He later on is admonished by a professor of natural philosophy for having wasted time studying the nonsense of alchemists. But Victor is young, beneficial in this case because his youth prevents him from becoming too rigid. He retains some suspicion about the merits of modern science, and is not altogether convinced about the so-called fallacies of the occultists and alchemists. Concerning the contempt of his professors for the occult arts, Victor remarks, ‘I was required to exchange chimeras of boundless grandeur for realities of little worth’.10 To counter this, another of Frankenstein’s professors proclaims:

‘The ancient teachers of this science [the occultists and alchemists] promised impossibilities and performed nothing. The modern masters promise very little: they know that metals cannot be transmuted and that the elixir of life is a chimera.’11

Victor later on meets up privately with this professor, who reveals his admiration and appreciation for Agrippa, Paracelsus, and their like, saying,

‘The labors of men of genius, however erroneously directed, scarcely ever fail in ultimately turning to the solid advantage of mankind’.12

Victor then devotes himself wholeheartedly to the study of modern chemistry, at which he excels. He then learns how to vitalize and bring life to dead body parts, which in so doing, eventually leads to his creation of the monster, something he had originally hoped to be beautiful, but which turns out to be hideous. Disgusted, Victor abandons the monster. This monster is sentient, however, and is deeply confused, hurt, and angry at the isolated predicament he finds himself in. The rest of the novel basically centers on the monster's quest for vengeance (in so doing, murdering several people close to Victor, but not without first appealing to Victor to create a companion for himself, so as to relieve him of his great loneliness. Victor considers doing so, but decides against it). The novel ends with Victor, bent on destroying his creation, dying of illness on a boat in the Arctic. The monster is devastated by Victor’s death, and vows to destroy himself. He jumps onto an ice raft, and disappears.

There are several important conventional themes in Frankenstein. These are:

1. The creation of life and sentient intelligence by the human hand, employing science.

2. The loss of control of this creation, and a general reflection on the dangers of science without adequate conscience.

3. Reaction to appearances, and the power of perception to mold our experience. (Victor Frankenstein is initially repelled by the appearance of his creation, and cannot overcome this reaction, leading to his abandonment of the creature, and its subsequent desire to seek vengeance for this).

The esoteric themes in Frankenstein are also there, if less obvious:

1. The need to distinguish between the inner sciences (occultism and alchemy in particular) and the outer sciences (chemistry in particular), by not confusing domains of experience and consciousness.

2. The esoteric meaning of the ‘golem’ and the ‘homunculus’.

3. Overcoming mortality via the science of inner creation (the ‘Body of Light’).

4. The Gnostic theme of flawed creation, via the Gnostic myth of the Demiurge who created the universe, and the passive role of the ‘true God’.

Occultism and Alchemy

These areas of study are notoriously misunderstood. On the one hand, there are the credulous who, lacking the capacity for critical thought (or angrily rebelling against it), are willing to embrace any paradigm, no matter how bizarre. Many of these may seem to conform to James Webb’s view of occultism as a realm of refuge for those disturbed by the dehumanizing elements of science. Occultism, with its central philosophy of ‘Man is a microcosm of God’, seems a safe vanguard against the cold mechanicality of the hard sciences. (Copernicus, Galileo, and Darwin may have seriously diminished the importance of the human being in the cosmic scheme of things, but occultism and the great esoteric traditions are based entirely on Shakespeare’s ‘Man is the measure of all things’).

On the other hand, there is the conventional academic view of occultism, alchemy, and related matters as little more than primitive proto-sciences, ignorant and base attempts to escape the dark dogmas of religion, but not yet at the intellectual honesty of ‘true’ science. This at times condescending perspective suffers from a surprisingly simple defect, that being the failure to differentiate domains of conscious experience (such as the subjective from the objective). It’s as if it rarely or never occurs to those who put forth this view that real occultism and alchemy were about more than just primitive attempts to gain power by manipulating matter.

There are, in fact, several levels of understanding within the occult sciences; the most profound of these are best described as esoteric traditions. The word ‘occult’ simply means ‘hidden’ or ‘secret’. The word ‘esoteric’ means ‘inner’, and in reference to spiritual teachings, refers to the inner teachings accessible to those ready to look deeper into their own nature. (Jesus even makes reference to this in the New Testament, when he says, ‘He who has ears, let him hear…’). In the spiritual realm, that the ‘inner’ has frequently meant ‘hidden’ or ‘secret’ has been natural, if for no other reason due to the intolerance shown by the Christian church, in particular, down through the centuries toward esoteric teachings. These teachings became hidden and secret for a reason, a reality perhaps never better demonstrated than by the discovery of the famed Gnostic Gospels in a cave in Nag Hammadi, Egypt, in 1945, where they had been secreted away for some sixteen centuries to escape the book-burning edicts of the Church that began around the 4th century CE.

The essential difference between the esoteric paths (Gnosticism, alchemy, Kabbalah, and so forth) and mainstream Western religion (orthodox Jewish, Christian, and Islamic doctrine) is the role of the individual in relation to Divine. The esoteric paths aim to guide the individual into a realization of their true nature, which is viewed as ultimately being ‘at one’ with the Divine. Conventional Western religions do not teach this, and regard any such lofty spiritual ambition as both foolhardy and heretical. One of the great Christian mystics, Meister Eckhart (1260-1327), was declared heretical by Pope John XXII two years after his death, in part for ‘revealing secrets’ and in part for teaching the core esoteric doctrine that Man and God can be, essentially, One. For a person awakened to their true nature, Eckhart wrote ‘There is no difference between him and God; they are one’.13

The occult tradition is ultimately about the study of the deepest truths of consciousness—essentially, the science of the inner realms. The word, however, has been notoriously tarnished, and in particular by the media of film and popular literature. Worse, it tends to get associated, consciously or not, with the word ‘cult’, even though the two words do not share a common etymological root. (‘Occult’ derives from the Latin occultus, meaning ‘hidden’ or ‘secret’; ‘cult’ springs from the Latin cultus, a word with various meanings, including ‘culture’, ‘worship’, and ‘reverence’). The word ‘cult’ in modern times is usually used in a pejorative fashion, essentially referring to any organized group that is demonstratively destructive, or more subtly, one simply disagrees with (or condemns).14

One of the more important branches of occultism down through the centuries has been alchemy. This is an ancient field of study and practice that has roots in China, Egypt, central Asia, and Europe. Alchemy is regarded by modern day science as the precursor of chemistry, and this is undoubtedly true to some degree. However alchemy has different levels to it. There is the strictly physical element that has been concerned with things such as manufacturing gold (more the European focus), or producing an elixir that could result in bodily immortality (more the Oriental concern). There is also the esoteric alchemy, concerned with spiritual transformation, in which the physical alchemical elements (sulfur, mercury, salt, and so on) and rich alchemical symbolism (green and red lions, dragons, hermaphrodites, etc.) are understood to represent psycho-spiritual realities and processes of personal initiation and transformation. This inner aspect of alchemy came to be increasingly abandoned, especially around the time Shelley was writing Frankenstein, in the wave of general excitement connected to the birth pangs of modern science. The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn (an occult society founded in 1888 by three London Freemasons) taught spiritual alchemy to some extent in its ‘knowledge lectures’, but it was the Swiss psychotherapist Carl Jung who openly rescued alchemy from oblivion in the mid-20th century, brilliantly revealing its symbolic depth and treating it as a means for psychological interpretation. (Jung wrote a great deal on alchemy, writings collected mostly in his works Psychology and Alchemy and Mysterium Coniunctionis).

In the novel, young Victor Frankenstein

initially embraced the occult arts, then waffles between them and modern

chemistry, until finally coming over to the new science for good, leading up to

the creation of his monster. The figures of occultism Shelley mentions in the

novel were chiefly Agrippa, Magnus, and Paracelsus. Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa

(1486-1535) was an important German magus, alchemist, and author of the vastly

influential Three Books of Occult

Philosophy (written by 1510, first published in complete form in 1533). The

book is a massive Renaissance encyclopedia of ritual magic, and is the main source

book for most significant schools of Western occultism since the 19th

century.

In the novel, young Victor Frankenstein

initially embraced the occult arts, then waffles between them and modern

chemistry, until finally coming over to the new science for good, leading up to

the creation of his monster. The figures of occultism Shelley mentions in the

novel were chiefly Agrippa, Magnus, and Paracelsus. Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa

(1486-1535) was an important German magus, alchemist, and author of the vastly

influential Three Books of Occult

Philosophy (written by 1510, first published in complete form in 1533). The

book is a massive Renaissance encyclopedia of ritual magic, and is the main source

book for most significant schools of Western occultism since the 19th

century.

One of Agrippa’s chief predecessors was Albertus Magnus (1200?-1280),

Dominican bishop, theologian, philosopher, and magus. Albertus died in Cologne,

the same German city that Agrippa was born in, raising the possibility that the

latter had paid homage, in his youth, to the tomb of the former (which can be

seen to this day in the crypt of St. Andreas church), given how consumed with

the occult sciences Agrippa had been at a young age—he wrote Three Books of Occult Philosophy at

around twenty years old, similar to the age Shelley was when she published the

first edition of Frankenstein.

Albertus had been a marked influence on two pillars of Western civilization,

the Italian poet Dante (and Mary Shelley was reading Dante when she was working

on Frankenstein) and the Catholic

theologian Thomas Aquinas (who had been a direct student of Albertus). In

addition to being a religious ‘authority’, Albertus was a great scholar,

considered one of the most widely learned men of his time. He is known to have

embraced astrology as an occult science, although this is not unusual for his

time, when astrology was held in the same esteem that astronomy is today.

Paracelsus

(1493-1541, seen on the right)—whose full name was the marvelously bombastic Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von

Hohenheim—was an important Swiss botanist (considered the first), alchemist,

occultist, and philosopher. Though is generally credited with being one of the

key figures bridging ancient physical alchemy with the first glimmerings of