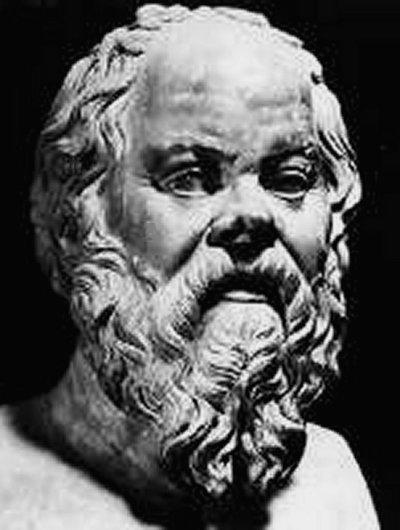

Socrates is a legendary figure in Western philosophy and, as

with most ancient sages, not a clearly defined historical character. Some facts

about him are known.1 He was born in 469 BCE and died seventy years

later in 399 BCE, both in Athens. He was the

quintessential seeker of truth, and his life was dedicated to the discovery of

the essence of who we are. His timeless maxim: ‘The unexamined life is not

worth living’ is testament to the powerful resolve that echoes the creed of

awakened sages everywhere, which is that none of the ‘treasures’ of the world

offer anything of ultimate worth, and that only the absolute truths of Reality,

and of our essential nature, are worth pursuing. More to the point, these

priceless truths can only be discovered via the hard work of self-examination.

With this one insight alone Socrates sets the stage for the modern paths of

work on self for the purposes of uncovering our greatest potential—and how such

potential does not have a real hope of manifesting if we do not make it the

main priority of our life.

Socrates is a legendary figure in Western philosophy and, as

with most ancient sages, not a clearly defined historical character. Some facts

about him are known.1 He was born in 469 BCE and died seventy years

later in 399 BCE, both in Athens. He was the

quintessential seeker of truth, and his life was dedicated to the discovery of

the essence of who we are. His timeless maxim: ‘The unexamined life is not

worth living’ is testament to the powerful resolve that echoes the creed of

awakened sages everywhere, which is that none of the ‘treasures’ of the world

offer anything of ultimate worth, and that only the absolute truths of Reality,

and of our essential nature, are worth pursuing. More to the point, these

priceless truths can only be discovered via the hard work of self-examination.

With this one insight alone Socrates sets the stage for the modern paths of

work on self for the purposes of uncovering our greatest potential—and how such

potential does not have a real hope of manifesting if we do not make it the

main priority of our life.

Socrates lived during the fertile explosion of wisdom that occurred, especially in Greece, India, and China, between approximately 600 and 300 BCE. During that time there came the Buddha and Mahavira in India, Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu in China, and Heraclitus, Socrates, Diogenes, Plato and Aristotle in Greece. (Some purists of transcendent wisdom would question Plato and Aristotle’s inclusion on that list, particularly the latter, who was not a mystic; but their sheer influence on Western philosophy, esotericism, and science warrants mention).

Socrates wrote nothing. What we know of him is via others, mostly his famed student Plato. But what most people recognize first about Socrates, if they recognize anything at all, is the dramatic manner of his death. Although arguments have been advanced by more recent historians that the causes behind this death may be more complex than is usually supposed, what is known is that he was condemned to death for ‘corrupting the youth of Athens’ via his relentless philosophical inquiry, and in specific, his constant questioning of authorities. This, along with the quality of his wisdom, makes him the awakened and courageous sage par excellence.

Throughout history radically awakened sages—in the rare times during which they’ve emerged—have usually met with difficulties, particularly if they have been influential. This is because their message generally runs counter to the political and religious zeitgeist of their times. Deeply realized sages are rarely good diplomats. This is so because the values of the world are centered on survival, above all else—whether that survival be connected to the urge of a ruling secular regime to perpetuate itself, or of an ideology or religious dogma to maintain control over the masses. Put simply, traditional religious or secular power almost never willingly yields control, even if they have become manifestly corrupt. Awakened sages bring a message that more than anything has to do with the inner freedom of the individual, the empowerment of them as a liberated and awakened person. Political or religious organizations are, generally speaking, not interested in that sort of person and in fact tend to automatically seek to control them because of their potential to be subversive; in particular, to disturb the young and turn them away from serving the ruling state or church.

Courage is an essential quality of deep awakening, because is can be daunting to peer into the face of the ego. However, in seeing the truth we gradually become more fearless in the face of illusion. When a dreamer recognizes that they are dreaming, therefore becoming awake in so doing, they naturally lose much of the fear of the dream they inhabit. That does not mean they become reckless or immature in their actions. It simply means that they become free of the terrible fears gripping one who is attached to their dreams and who is controlled by illusions.

Socrates was the embodiment of intellectual and spiritual courage, much like Jesus, another sage who was executed for his refusal to compromise his views. In modern times in the West we take for granted things like ‘freedom of speech’, but for much of the history of civilization there was no such thing (as there is no such thing for substantial parts of the human race even now). It has always been easy to be killed for speaking out, or for refusing to recant one’s words. This was true even in the Athens of Socrates’ time, which in many ways was a relatively advanced culture.

Socrates was the archetypal shit-disturber. His whole approach was based on relentlessly questioning dogma, so-called ‘certainties’, and the lazy thinking that is based on taking on the views of others without ever bothering to truly look closely at them. But he wasn’t doing this merely for the sake of disturbing apple-carts. He had a specific purpose, what Gurdjieff called an ‘aim’, and that was to instill in others the understanding that the ultimate purpose of reason, and self-examination, was to discover what is pure, good, and sacred within us—our supreme potential. He called this agathon, or ‘absolute Good’. The modern term, as borrowed from our great Eastern wisdom traditions, is ‘enlightenment’. For Socrates, the true purpose of human life is to attain this.

There are not a lot of facts about Socrates’ life, and most of what he taught, as conveyed by Plato, was colored by Plato’s additions and insights. But this is a secondary issue; what matters are the insights themselves. There were other philosophers who wrote about Socrates—Xenophon, Aristophanes, and Aristotle being three—but Plato’s writings, which have survived the tempest of time, are considered by most to accurately reflect the master’s teachings.

As recorded in Plato’s Apology, Socrates during his trial (that resulted in his being condemned to death) proclaimed:

For I spend all my time going about trying to persuade you, young and old, to make your first and chief concern not to care for your persons or your property more than for the perfection of your souls.

That level of commitment is typically common to radical sages—insisting on the ‘all or nothing’ approach. We find this theme time and again amongst the wisest. They fearlessly prioritize the search for wisdom and truth above all else, even if this requires trenchant criticism of the mediocre values of mainstream life and even if this means being criticized or condemned in the eyes of the public.

Socrates was renowned for dialectics (especially in its simple form of questioning and answering), and in particular, something called ‘Socratic method’. This is basically a type of cross-examining, via constant questioning, of anyone who holds a strong belief about something, so that they can deepen their understanding of the issue they hold beliefs about—or until they are shown the inevitable contradictions held in their views.

Socrates is renowned for once having been declared, by the Delphi Oracle, the ‘wisest man in Athens’. He famously objected to this, believing that he had no real wisdom at all. To prove his point he then set about questioning several so-called wise people in Athens, to find out if they indeed knew more than he. What he found in each case, however, was that the people he was questioning actually believed that they were wise when he could see that they were not. In the end, Socrates concluded that the Delphi Oracle had been right all along, and that, in fact, he was the wisest person in Athens—but only for the reason that he alone realized that he was not truly wise at all. That is, he had the wisdom of recognizing his own ignorance. In other words, he was not pretending to be anything—which is arguably the greatest fault of ‘truth-seekers’ and ‘spiritual people’ (see Chapter 1).

The ‘ignorance’ Socrates refers to is not the ignorance of being ill-educated but rather the profounder ignorance born out of the realization that conventional knowledge cannot truly penetrate to the heart of matters. For example, we can ask ourselves the simple question ‘what is the color green?’ Even with modern knowledge of wavelengths and reflected light and so on, we are still left with the realization that all of our knowledge amounts to labels we put on the thing we call ‘green’. They do not truly capture the thing in itself, for the simple reason that conventional thinking separates us from what it is observing. This basic separation allows us to make detailed observations about the appearance of the thing, but not to truly know it directly. Worse, it sustains the illusion that there really are ‘things out there’ that are truly isolated and disconnected from the totality of all that is, and from our own consciousness. In short, Socrates declares his ignorance not to denounce knowledge, but to point the way to a newer, deeper form of knowledge. This is consistent with what all awakened sages teach: in order to realize the true, we must first recognize and relinquish the false.

The wisdom of ‘not-knowing’ is a theme commonly echoed in the Zen tradition in particular. In many ways Socrates was the first Zen master (the traditionally accepted first Zen master, Bodhidharma, lived a thousand years after Socrates). Socrates, consistent with the Zen tradition, was a vocal critic of pretentiousness in all its guises, and perhaps never more so than in the realm of spiritual pretentiousness. He was merciless in exposing falsehood, and this of course made him enemies, as it typically will do for a sage who is both wise and influential. In particular he was critical of the ‘sophists’ of his time, philosophers who he saw as posing as wise (and at times earning money for it), but who in fact lacked real wisdom—similar to how Jesus was to be vociferously critical of some of the priesthoods of his time.

A main target for Socrates in his criticism of sophists was the language games he saw them engaging in. This was somewhat ironic because Socrates himself was reputed to be a master of language—capable, as one commentator put it, of arguing any point of view and making it seem good. However, he used his skill with language to make those who hid behind words aware of their weaknesses. Like all realized sages, he saw through the thicket of language and penetrated beyond the dull thinking that categorizes so many who are merely parroting what they’ve been told is true. In short, Socrates’ overwhelming aim was to enable people to truly think for themselves.

Some of Socrates’ contemporaries reported that as a young man the philosopher had some interest in natural science—in the things of the world—but that this faded as he realized the overriding importance of discovering the truth and nature of consciousness, of our own being. One modern historian, in referring to Socrates, suggested that at some point he must have voiced St. Augustine’s famous line, ‘I no longer dream of the stars’.

This is a deceptively simple point, but crucially important for one who seeks truth. The ‘things of the world’—be they ugly, or the wonders and beauties of Nature—are all enormously seductive, and all have a similar effect, that being the tendency to pull us out of ourselves. To ‘dream’ is to forget ourselves, to become lost in the dream and its terrors and wonders. There comes a time when we tire of this, much how we can tire of watching a fireworks display. We begin to crave the vaster and deeper truths of being—the being that we are.

Socrates’ teaching boils down to the famous maxim on Apollo’s temple at Delphi: Know Thyself. This is the time-honored creed of awakening. It is, of course, a teaching that can be wildly abused, as the endless examples of self-absorption disguised as ‘self-knowledge’ in modern times attest to. ‘Know thyself’ properly understood is not narcissism, nor does it invite it. In spirit it is closer to the Zen maxim ‘To know yourself is to forget yourself. To forget yourself is to be enlightened by all things’. What this means is that in examining, with deep honesty, our own mind and personality, we enter into a process of deconstruction in which cherished illusions are taken apart, or fall way (depending on how well we cooperate with the process). As these illusions dissolve we literally begin to ‘forget’ our past delusions and neuroses. We lose the annoying self-consciousness that arises from thinking ourselves special—in either the superior or inferior forms. We become comfortable with who we are, which in turn prepares us for deeper awakenings.

There is an interesting paradox inherent in Socrates, as

there is in all radically awakened adepts, and it is this: while seemingly

darkly pessimistic, he is in fact a supreme optimist. By critiquing so much

about human life, and by being stubbornly adversarial and judgmental of

conventional values and mediocre thinking—to the point where such stubbornness

earned him a death sentence—he is actually a true optimist, because he holds

that ultimate truth (which, naturally, he claimed existed) is also ultimate

good; and that moreover, this state of being is truly attainable.

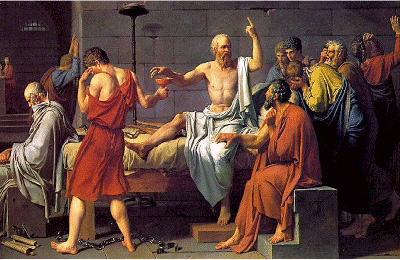

A famous element of the legend of Socrates was the manner of his death. Condemned in a dubious trial for 'not acknowledging the gods' ('impiety' or 'irreligiosity' were the terms) and 'corrupting the youth of Athens', he was sentenced to be poisoned by drinking hemlock. He had the opportunity to flee the city afterward, but declined, and voluntarily drank the hemlock, dying with both awareness and dignity.

A famous element of the legend of Socrates was the manner of his death. Condemned in a dubious trial for 'not acknowledging the gods' ('impiety' or 'irreligiosity' were the terms) and 'corrupting the youth of Athens', he was sentenced to be poisoned by drinking hemlock. He had the opportunity to flee the city afterward, but declined, and voluntarily drank the hemlock, dying with both awareness and dignity.

He has been called the 'first martyr of free speech', but in fact he was something much more. He was a pointer to both what is possible for a human being, and what is ill in the human world -- sickness of the soul -- that has been at the root of human suffering for recorded history and doubtless beyond. Great sages characteristically make others aware of this illness by drawing a stark contrast between the values of higher truth, and the intolerances and agendas of both worldly authorities and the mass man.

___________________________________

The figure of Jesus is of course of towering significance in

Western civilization (an extraordinary fact alone, given that his ministry

lasted only for around three years and that he died a young man, in his

mid-thirties). A tremendous edifice of myth and legend has been built around

him. Despite the sheer confusing bulk of this history, and its frequently

clumsy (and ugly) interfacing with politics, it is possible to break the matter

down and see Jesus in three main lights: the ‘historical Jesus’, the ‘dogmatic

Christ’, and the ‘awakened sage’.2

The figure of Jesus is of course of towering significance in

Western civilization (an extraordinary fact alone, given that his ministry

lasted only for around three years and that he died a young man, in his

mid-thirties). A tremendous edifice of myth and legend has been built around

him. Despite the sheer confusing bulk of this history, and its frequently

clumsy (and ugly) interfacing with politics, it is possible to break the matter

down and see Jesus in three main lights: the ‘historical Jesus’, the ‘dogmatic

Christ’, and the ‘awakened sage’.2

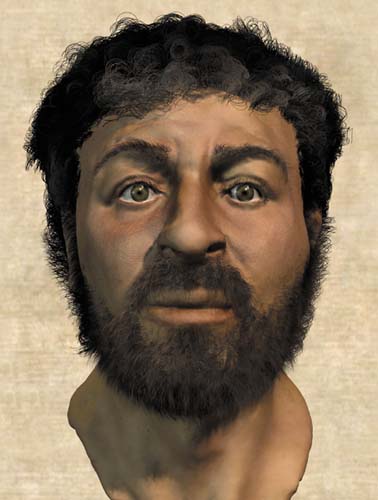

The ‘historical Jesus’ is exactly that, the Jesus of history. However, this matter has represented a real problem for historians, because outside of the New Testament there is very little corroborating evidence for the existence of a Jewish messiah-sage who was convicted by Pontius Pilate and crucified around 30 CE. (The image on the right was crafted by a National Geographic artist, based on racial traits common to a man of that time and place -- it is much more likely that Jesus looked something like this, rather than the stereotypical blonde European appearance). Nevertheless, the material in the New Testament and related apocryphal gospels is considered substantial enough for scholars to attempt to tease out a reasonably clear picture of what this man was about. The historical Jesus is frequently at odds with the Jesus of organized Christian religion, and so there is, naturally, a great deal of controversy in all of this.

The details of the research into the historical Jesus, and how the results up to now have contrasted (and often clashed loudly) with the Christ of faith—the ‘dogmatic Christ’—are fascinating but fall outside of the scope of this book. Suffice to say, a few brief conclusions generally reached by scholars and historians can be mentioned here in passing. One of the themes (and purposes) of this book is to make us aware of our conditioning (which often involves getting our buttons pushed); looking into the research around the historical Jesus can aid in making us more aware of our religious conditioning by close examination of our reactions as we read. This is important because the simple fact is that Christianity claims more adherents than any other faith on Earth—approximately one-third of the human race, or, as of this writing in 2010, over two billion people. Moreover, Christianity (or more accurately, Judeo-Christianity) is deeply intertwined with the cultural history of Western civilization. Even those postmodern souls who claim indifferent agnosticism or ‘liberated’ intellectual atheism have been influenced by Judeo-Christian ideals, values, and limitations more than they are usually aware of.

Critical scholarship applied to the life of Jesus—the attempt to separate the man from the enormous cloud of myth, superstition, and legend—had its roots in the 18th and 19th centuries via the work of some brave German scholars, but really began to hit its stride in the mid 1980s with the founding of the ‘Jesus Seminar’ by Bible scholars Robert Funk, John Dominic Crossan, Marcus Borg, and others, under sponsorship of the Westar Institute. This group, aided by up to two hundred (mostly liberal) scholars, eventually produced a work that gave a cautious estimation of what exactly Jesus probably did and did not say, based on the words traditionally ascribed to him. The Jesus Seminar concluded that 82% of the words that he is supposed to have said, according to the four traditional Gospels, were ‘not actually spoken by him’. This, predictably, unleashed a firestorm of controversy from conservative Christians, who then attempted to attack the findings of the Jesus Seminar from many angles; one result from the backlash was that some Seminar Fellows ended up having to resign their teaching posts.

Dogma, especially when tied to many vested interests, never dies easily. Equally so, our own ‘personal dogma’—that is, the conditioning that we’ve been programmed with and have come to believe is ‘mine’—does not die easily either. Every truth-seeker sooner or later faces their conditioning, and it can be surprising how stubborn this conditioning can be, and how much clarity and determination it can take to shake it off.

Many things emerged from the critical analysis of these hard working scholars concerning the gospels and other associated writings, and many of their conclusions were published in the early 1990s, a heyday for a wider public outreach by scholars of the historical Jesus. Amongst these have been: no evidence that Herod ‘murdered babies’ en masse in the infamous ‘slaughter of the innocents’ in an attempt to eliminate Jesus as a possible rival king; that Jesus was likely born in Nazareth, not Bethlehem; that he never claimed to be the Messiah, or the ‘Son of God’; that he was not born of a ‘virgin birth’; and that the resurrection story, as literally told, is almost certainly a fairy tale.

The number of internal contradictions in the gospels concerning the history of Jesus, his genealogy, the manner and place of his birth, and so forth, are so many that it soon becomes clear to the unbiased reader that the New Testament is not a true historical document, but rather a document of faith. Even most Christian faithful would not ultimately deny that, despite the fact that the Bible does contain plenty of actual history. As the German historian and Bible scholar Rudolf Bultmann pointed out, ‘only the crucifixion matters’; that is, for an actual inner or mystical connection with Christ, or faith in what he represents, the more outlandish New Testament legends and myths are not necessary.

What has become increasingly clear is that the historical Jesus of Nazareth is really not reconcilable with the Jesus of faith—the Incarnation (and Son) of God. In a span of around three hundred years Jesus of Nazareth became the Christ of the Nicene Creed as ratified by Emperor Constantine and a few hundred bishops in Nicaea in 325 CE. He went from being a wandering Jewish sage, perhaps similar in some respects to a youthful version of Siddhartha Gautama (the historical Buddha), to God Himself, the Logos, the Infinite One, both the Son of the Father and the Father Himself, forever distinct from mere humanity and human beings. He became the Christ of dogma.

However, what is of real interest to us here is the ‘awakened sage’ Jesus, for it is clear that such a man existed, regardless of what he was called, what he looked like, where he lived, whether or not he bedded Mary Magdalene and left behind a mysterious bloodline, whether or not he was the Son of God, and other related matters. It’s even possible that the ‘Jesus’ of scripture was a composite character of sorts, possibly how Lao Tzu (author of the famed Tao Te Ching) is occasionally speculated to have been, owing the scant amount of historical data on him.

The point is that it doesn’t matter who Jesus was. What matters are the teachings ascribed to him—at least those that appear to be clearly wise—and even more to the point, how we can apply them to our own awakening process. Below, some of those teachings are considered. For the record—not that we need their blessing to continue—but the ‘Jesus Seminar’ scholars concluded that most of the teachings we’re about to look at were part of the small percentage of words ascribed to Jesus that he very probably did say. (Although it is perhaps not coincidental that the words I select below to comment on are also manifestly wise).

Teachings

A particular quality of Jesus that emerges from the gospels (once purged of fanciful legend, thundering prophecies, miraculous powers, threats of gnashing and wailing and hellfire, and related crudities) is that of a rebellious and ruthless lion. His more recognizable teachings are sharp and uncompromising (a quality that probably contributed toward his eventual persecution). He was similar to other radical sages and ‘dangerous masters’ in that he specialized in cutting against the grain of convention—in short, he was the quintessential alarm clock, come to disturb sleepers and rouse them from their sleep—even if such an approach ultimately cost him his life. What follows are some of Jesus’ more profound insights.

Perhaps the clearest example of Jesus as radically awakened sage is this statement:

But seek first the kingdom of God, and his righteousness, and all these things shall be added unto you. (Matthew 6:33)

That is the time-honored rallying cry of one awake to their true nature (and, admittedly, an easy one to twist to serve a political agenda). The mystical text A Course in Miracles phrases it as ‘Be vigilant only for God and His kingdom’. The classic text of Renaissance high magic, The Sacred Magic of Abramelin the Mage, refers to it in its teaching that the mystic must first contact his ‘holy guardian angel’ (his direct link to God), prior to doing anything else.

The central idea that runs through all legitimate transformational work is that prioritization in life is crucial. Our life tends to reflect how we prioritize things. If our chief ‘God’ is money, or relationships, or sex, or status, or power, or any host of more negative ideals, that will be mirrored in our life. For one desiring to be awake to their highest potential, they must cultivate passion for that and put it as number one on the list. Our life needs to be oriented around the intention to be awake. That doesn’t mean we become obsessed with it. Our task is to live a balanced life, but one that has a central conscious aim—as Gurdjieff put it, to ‘remember yourself, always and everywhere’.

Most people, especially in these current eBay and Walmart times, tend to be dabblers and samplers, trying out something before rushing off to try out the next thing. Perhaps no better metaphor for this sheer superficiality can be found in the modern online social networking phenomenon, where on such sites as Facebook individuals have lists of hundreds (or even thousands) of ‘friends’, the vast majority of whom they have no direct communication with (and probably do not even know), and who can scarcely be recognized as a friend in the actual meaning of the word. We live during of time of vast breadth but little depth. Everything is spread wide and very thin, owing largely to the advances in communication technology. Naturally there are some benefits from this, but there are serious drawbacks, one of which is a diminished effect on attention spans, restlessness and cynicism, and a knowledge-diet of ‘sound-bites’, snippets, YouTube mini-movies and endless related mundane downloads of trivia.

All this largely works completely counter to the spiritual impulse, which requires focus, a single-minded passion for depth, and a willingness to develop a capacity for sustained attention via meditation practice and close study of the words of awakened sages. In that regard, sages like Jesus are a good antidote for these times, provided we actually hear what they are saying.

Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. (Matthew 5:3)

‘Poor in spirit’ does not imply a false piety brought about by cultivated poverty, either of personality or material belongings. It rather refers to the opposite of pride. By ‘pride’ I specifically mean the need to be right about things. There is perhaps no greater barrier to our inner awakening. To grow consciously means to develop a deep willingness to be wrong about anything that is in the way of our deeper realization of the nature of our being, and of Reality.

The old Zen parable of the Zen master serving a cup of tea to a young, intellectually arrogant student holds here. In the parable the master keeps pouring the tea, even as it overflows and spills on the floor. The student eventually asks him what he doing—can he not see that this cup is already full? ‘So too,’ responds the master, ‘is your mind. It is too full of knowledge, and you are too full of yourself. There is no room in you to learn anything new.’

To be proud is not, in this sense, to be confident or to have ‘good self-esteem’, or anything like that. It is rather to be too full of ourselves owing to a great need to always be right about matters. Needless to say, when we have a strong attachment to being right about things, we stand very little chance of truly waking up. Our self-control (and control of others) is suffocating us and making legitimate growth impossible. We need to be right about things either because we have been badly hurt in past relationships (and we now equate ‘being wrong’ with getting hurt), or because the idea of losing control brings up too much anxiety for us. The anxiety and general fear of being shamed, or of losing control, commonly underlies excessive pride.

Blessed are they who hunger and thirst after righteousness, for they shall be filled. (Matthew 5:6)

The word ‘righteousness’ is often seen in a dubious light, especially during these politically sensitive times, along with an acute awareness of the wreckage caused by righteousness in general, especially of the religious or political sort. Modern psycho-spiritual language also reflects this, with terms like ‘self-righteous’ often used to denote a stubborn-mindedness that erodes relationships (the ‘pride’ mentioned above).

The word ‘righteous’ does, however, have an original positive meaning, that being ‘genuine’ or ‘excellent’; it derives from the old English term ‘rightwise’, which was itself a combination of ‘right’ (meaning, originally, ‘straight’) and ‘wise’. So to be rightwise, or righteous, was to be both trustworthy and wise. The Biblical English translation was rendered with that original meaning of righteousness in mind, so the saying can be read as ‘Those who hunger and thirst after true wisdom are blessed’.

To ‘hunger and thirst’ means, in this context, to desire above all else. Here again we see the radical, uncompromising nature of Jesus’ message, consistent with all deeply awakened sages. Desire for the highest truth must be the guiding light of our life.

Blessed are the merciful, for they shall obtain mercy. (Matthew 5:7)

To be shown ‘mercy’ is to be forgiven for our offenses, whatever they have been (or however others have perceived them). The key issue here is not that of the standard pious forgiveness, which is usually spurious (‘In order to make an outward display of my character I’ll forgive you, but privately I’ll continue to think you’re an asshole and I’ll never trust you again’.) True forgiveness is something different. It is directly a function of being awake. When awake to the interconnectedness of life we begin to understand the foolishness of lazily condemning others when we have not really looked in the mirror. (There is certainly room for accurate assessment of others, or appropriate use of judgment, but this is another matter. For now, we can recognize that the vast majority of judgment arises from personal agendas and the need to blame others for our problems in life).

By ‘giving mercy’—releasing others from the tight mental boxes we’ve put them in, and being willing to see their deeper underlying connection with us (just as everything is connected)—we let them go, so to speak, and in doing so, we are in turn ‘freed’. To truly forgive someone is not just to free them, but more importantly, it is to free ourselves from our attachment to them. To hate someone is to remain attached to them. The more ‘enemies’ we have, the less free we are.

Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God. (Matthew 5:8)

This line is often given as an example of Christ’s moral teachings—be a good saint who doesn’t fornicate or do other ‘bad’ things, etc. However it must be seen in a deeper light. ‘Pure’ originally simply meant ‘unmixed’. If something is unmixed, it is not diluted, and thus is both strong and original. To be ‘pure in heart’ is, from that perspective, to be untainted by the ideas, agendas, and conditioning put upon us by others.

Of course the simple truth is that none of us escapes being conditioned by the ideas and agendas of others. The task is to begin bravely recognizing this conditioning, and moving beyond it. We have to recognize just what is truly ours, and what we have merely borrowed, inherited, or otherwise uncritically bought into. To begin to let go of our borrowed ideas is to begin to become truly ‘pure in heart’. This type of freer heart is capable of recognizing deep truth.

Meditation and all forms of legitimate transformational work ultimately amount to a type of de-conditioning—or as one psychotherapist once put it, ‘de-hypnosis’. We have to un-learn much, in order to create the space inwardly, so to speak, to allow fresh, clear, and natural wisdom to arise. To ‘see God’ is to open the inner eye, to become sensitive to the immensity of being and existence. ‘Purity of heart’ can be understood more as becoming ‘inwardly uncluttered’ rather than attaining to some forced moral standard.

Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God. (Matthew 5:9)

To be a ‘son of God’ means, in this context, to be

awake to our true nature. To be a ‘peacemaker’ is to be one who contributes to

the awakening of the human race, one who serves Truth. It is again a variation

of a consistent theme of Jesus’ teaching, which is that passion for Truth must

be our guiding light, and all our energies committed to that purpose. This is

not, of course, the same thing as becoming fanatic, or a proselytizer. To have

passion for awakening is not to be in the business of converting others (as if

there is any ‘thing’ to convert them to). It addresses rather the issue of

balance. That is, to commit ourselves to awakening is to have an inner practice

of some sort, but not to become

insulated from the world. Our ‘outer practice’ is how we serve, and that can be

done in endless ways, but it always involves some sort of participation in the

matter of sharing energy and consciousness with others. The word ‘peacemakers’

does appear very specific, but rather than conventional social activism it can

be seen as referring to those outer actions that support the activity of inner

work in the world, what in the East is sometimes called karma-yoga, or what the contemporary mystic Andrew Harvey has

called an element of ‘sacred’ activism. A simple example might be helping a

teacher one is inspired by, or assisting a wise person in helping to make their

work become more accessible to others, and so on.

To be a ‘son of God’ means, in this context, to be

awake to our true nature. To be a ‘peacemaker’ is to be one who contributes to

the awakening of the human race, one who serves Truth. It is again a variation

of a consistent theme of Jesus’ teaching, which is that passion for Truth must

be our guiding light, and all our energies committed to that purpose. This is

not, of course, the same thing as becoming fanatic, or a proselytizer. To have

passion for awakening is not to be in the business of converting others (as if

there is any ‘thing’ to convert them to). It addresses rather the issue of

balance. That is, to commit ourselves to awakening is to have an inner practice

of some sort, but not to become

insulated from the world. Our ‘outer practice’ is how we serve, and that can be

done in endless ways, but it always involves some sort of participation in the

matter of sharing energy and consciousness with others. The word ‘peacemakers’

does appear very specific, but rather than conventional social activism it can

be seen as referring to those outer actions that support the activity of inner

work in the world, what in the East is sometimes called karma-yoga, or what the contemporary mystic Andrew Harvey has

called an element of ‘sacred’ activism. A simple example might be helping a

teacher one is inspired by, or assisting a wise person in helping to make their

work become more accessible to others, and so on.

Blessed are they that have been persecuted for righteousness sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. (Matthew 5:10)

Blessed are ye, when men shall revile you and persecute you. (Matthew 5:11)

These two statements emit a sharp light that it will be difficult to look at for some. What they are basically saying is that one who aspires to be awake is not going to experience their life-path being reinforced by the world, by the mass man, or even (as is most likely) by one’s family. As Goethe once wrote, ‘Tell a wise man, or else keep silent; for the mass man will mock it right away.’ It was true in Jesus’ time, and it remains true today. To be awake in a sleeping world is to be seen as eccentric (or worse). The conventional way of putting it is that a ‘prophet is never recognized in his own country’, or a ‘genius is never recognized while they live’. However a more direct way of saying it is ‘the awake person is homeless, nationless, and unknown’. That is not grounds, of course, for resigning ourselves to a victim-position and giving up on the whole matter. But it is important to remember that our intention to be awake will usually not be recognized by most people; or worse, may even be actively opposed or undermined by them. None of that need be a real problem, however, and in fact we can simply use it to sharpen our practice and inner work, something like how a weight-lifter is strengthened by pushing against weights. And therein lays the real point. Being awake is not contingent on what others think of us, or how they see us—regardless of who they are. To get beyond that fear is one of the most significant barriers to surmount facing one who aspires to realization.

You hypocrite, first take the plank out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to remove the speck from your brother’s eye. (Matthew 7:5)

With this expression, Jesus reveals his psychological clarity, anticipating Freud’s views on ‘projection’ nineteen centuries later. The statement needs little comment. We have to practice what we preach, to walk our talk, if our search for truth is to be authentic, and more than mere show.

For whoever wants to save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for me will find it. What good will it be for a man if he gains the whole world, yet forfeits his soul? (Matthew16:25-26)

The main delusion of the sleeping person (or, in psycho-spiritual language, ‘the ego’) is the belief that our salvation comes from the things of the world. To commit to awakening is, in a sense, to lose our life—not our real life, but the life of dreams and illusions, the life that we have been conditioned with, and taught to believe in, by the world.

If anyone comes to me and does not hate his father and mother, his wife and children, his brothers and sisters—yes, even his own life—he cannot be my disciple. (Luke 14: 26)

A very powerful saying, full of the uncompromising edge and fire that is so indicative of radically awakened sages like Socrates, Hakuin, or Jesus. What he is really saying there is, again, the supreme importance of prioritizing the search for truth. ‘Hating’ father, mother, etc., is symbolic of placing everything below the intention to be awake. It may sound supremely selfish, but it is actually the reverse; in fact being asleep is synonymous with selfishness and utter inability to truly help anyone.

You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I say to you, Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be sons of your Father who is in heaven; for he makes his sun rise on the evil and on the good, and sends rain on the just and on the unjust. For if you love those who love you, what reward have you? Do not even the tax collectors do the same? And if you salute only your brethren, what more are you doing than others? Do not even the Gentiles do the same? You, therefore, must be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect. (Matthew 5:43-48).

What does it mean to love our enemies? It is more than a clever psycho-social device to disarm those who are opposed to us. The injunction is not to be taken superficially, as some false piety, some phony holiness. It rather is reflective of some of the deepest wisdom of mystical tradition, perhaps nowhere echoed more clearly than in these lines from the Tao Te Ching:

See the world as yourself.

Have faith in the way things are.

Love the world as yourself;

then you can care for all things (13).

The key is to see the world as us. That is one of the central teachings at the core of most wisdom traditions, but the way Jesus tackles it is unique, and so starkly radical that it immediately grabs our attention. Jesus here represents our capacity to forgive in a profound and radical way, to ‘be grand and mature’ in the truest sense of those words. When we react petulantly, vengefully, we diminish our spirit in some way, if only by reinforcing our attachments. Not that passionate expression is to be denied—it is rather that our passion is to be re-directed back toward a love of Truth. The surest way to do this is to stop wasting our passion, our life-force, on hating, on righteously condemning others, on ‘maintaining enemies’.

The passage quoted above from Matthew referring to God ‘making his sun to rise on the evil and the good, and sending rain on the just and the unjust’, gives a glimpse into the profound non-dualism found in the teachings of all deeply realized sages. Ultimate truth transcends human conventions of good and evil, of just and unjust, and embraces a much vaster totality in which nothing is disconnected from anything else.

The Crucifixion

Jesus, like Socrates, paid a heavy price for his brazen

teachings. His crucifixion—and, as Christians believe, his resurrection—are of

crucial importance to Christian faith. However I think there is a teaching

connected to the crucifixion that can be seen as a straightforward shedding of

light on the ‘crucifier’within each of us. Jesus was killed for what he claimed

to represent—truth. Accordingly, we can understand his execution, from the

esoteric perspective, as ‘killing truth’. And in fact, there is an element

within all of us (at least, practically all of us—perhaps a few rare souls are

free of this) that is in the business of killing off truth. A Course in Miracles makes reference to

the ‘murderous’ nature of the ego, in a section of its teachings called ‘It can be but myself I crucify’. It is

the part of our being that is so profoundly threatened by truth that it must

silence it no matter what:

Jesus, like Socrates, paid a heavy price for his brazen

teachings. His crucifixion—and, as Christians believe, his resurrection—are of

crucial importance to Christian faith. However I think there is a teaching

connected to the crucifixion that can be seen as a straightforward shedding of

light on the ‘crucifier’within each of us. Jesus was killed for what he claimed

to represent—truth. Accordingly, we can understand his execution, from the

esoteric perspective, as ‘killing truth’. And in fact, there is an element

within all of us (at least, practically all of us—perhaps a few rare souls are

free of this) that is in the business of killing off truth. A Course in Miracles makes reference to

the ‘murderous’ nature of the ego, in a section of its teachings called ‘It can be but myself I crucify’. It is

the part of our being that is so profoundly threatened by truth that it must

silence it no matter what:

There is an instant in which terror seems to grip your mind so wholly that escape appears quite hopeless. When you realize, once and for all, that it is you you fear, the mind perceives itself as split. And this had been concealed while you believed attack could be directed outward, and returned from outside to within. It seemed to be an enemy from outside you had to fear. And thus a god outside yourself became your mortal enemy; the source of fear. Now, for an instant, is a murderer perceived within you, eager for your death, intent on plotting punishment for you until the time when it can kill at last. (ACIM Workbook, #196)3

The ‘murderer within’ is vivid symbolism for all guilt and self-loathing, and all fear of relinquishing control—the control of our own identity, and the fear of being dominated, controlled, killed, by something bigger, and thus the fear of light and truth and life—the ‘Way’ represented by Jesus. There is a part of us that fears being ‘killed’ by truth, and so seeks to kill it first.

Truth is a fire and it does, in a very real sense, ‘kill’ us—the

part of us that is false, illusory, what the Buddha referred to as our

attachments, and the entire constructed edifice of the personal self that seeks

to wall itself off from the true reality of the infinite. In that sense, the

‘murderous’ and traitorous face of the mind represents what in us fears Truth,

and in particular, the consequences it will entail if we decide to commit our

lives to that.

Ultimately, we are all cowards in the face of radical, uncompromising spiritual truth, and if we are not busy with running from it, we are involved in undermining it. That does not mean, however, that we need crucify ourselves for this fact. Such a punishment has already been done; we need not repeat it. Our task is, rather, to ‘love our enemies’—to look deeply into the face of our fear, to summon compassion for it, and to penetrate beyond it with fearless passion for truth.

_________________________________

Milarepa: Reformed Sorcerer

Story

Jetsun Milarepa, the famous yogi-saint of Tibet, lived from

approximately 1052 to 1135 C.E.4 His name in Tibetan literally means

‘Mila who wears cotton’, referring to the extreme asceticism of his later

years, and the one piece of garment he owned during that time. Milarepa’s life

story is of the archetypal spiritual hero. Much as with other ancient sages

like Pythagoras, Lao Tzu, Socrates, and Jesus, little is known for sure about

the kind of person he was and what exactly his ‘life-script’ truly involved.

However, as with all myths and legends it is what the stories represent that, above all, carries weight and meaning. This is very much the case

from the perspective of ultimate spiritual truths, because from the deepest

perspective all stories, regardless

of whether they happened in physical reality or only in some scribe’s

imagination, are equally ‘legendary’ in the sense that they do not point to the

unchangeable existence of any discreet, separate entity we may know as a

‘person’ to whom these stories have supposedly occurred. They rather point to

the timeless message, which is always

of a deeper substance than the messenger, whether this messenger be fictive or

factual. Milarepa, regardless of how purely mythic his legend may be, is no

less or no more real than you and I in this moment. Our very personalities are,

ultimately, largely a collection of stories. These stories can, however, point

toward ultimate truths, and this is especially so in the case of legends that

surround awakened sages.

Jetsun Milarepa, the famous yogi-saint of Tibet, lived from

approximately 1052 to 1135 C.E.4 His name in Tibetan literally means

‘Mila who wears cotton’, referring to the extreme asceticism of his later

years, and the one piece of garment he owned during that time. Milarepa’s life

story is of the archetypal spiritual hero. Much as with other ancient sages

like Pythagoras, Lao Tzu, Socrates, and Jesus, little is known for sure about

the kind of person he was and what exactly his ‘life-script’ truly involved.

However, as with all myths and legends it is what the stories represent that, above all, carries weight and meaning. This is very much the case

from the perspective of ultimate spiritual truths, because from the deepest

perspective all stories, regardless

of whether they happened in physical reality or only in some scribe’s

imagination, are equally ‘legendary’ in the sense that they do not point to the

unchangeable existence of any discreet, separate entity we may know as a

‘person’ to whom these stories have supposedly occurred. They rather point to

the timeless message, which is always

of a deeper substance than the messenger, whether this messenger be fictive or

factual. Milarepa, regardless of how purely mythic his legend may be, is no

less or no more real than you and I in this moment. Our very personalities are,

ultimately, largely a collection of stories. These stories can, however, point

toward ultimate truths, and this is especially so in the case of legends that

surround awakened sages.

The legend of Milarepa’s life tells of exceptional qualities. He started out as an innocent boy, became a destructive sorcerer, went through a profound remorse of conscience, followed that up with a purifying ordeal at the hands of a powerful taskmaster, and later attained to full enlightenment. There was an unusual degree of suffering in his ordeal, not just for himself, of course, but for those whom he’d harmed in his earlier years. It is rare in the lore of sages and mystics that criminals—let alone murderers—become awakened masters, and this is in large part what makes Milarepa’s story as compelling as it is.

As for the source of the story, this appears to come from the written records of a Tibetan scribe who lived about four hundred years after Milarepa. He reports that Milarepa was born in western Tibet, near the sacred Mount Kailas. At the age of seven his father died. His father’s property was then confiscated by a greedy uncle and aunt. Milarepa’s mother, angry and wanting revenge, eventually sent the young boy off to study with a Bon (shamanic) sorcerer, who proceeded to train him in harmful forms of magic, which included the alleged ability to alter weather patterns by harnessing certain destructive elemental forces.

Shamanism had been present in Tibet long before the arrival of Buddhism around the 7th century C.E. Tibetan (as well as Mongolian and Siberian) shamans were widely known and on occasion feared for their unusual powers. In pre-industrial, pre-scientific times, magicians and shamans and sorcerers were, in most respects, the only ‘wonder-workers’; the fact that many of these ‘wonders’ occurred only in the perception or imagination of others, did not diminish the power and esteem that these people were mostly held in. Tibet in particular has a history of rich lore on the topic of fantastic shamanic powers, to an extent that the wonders credited to Jesus in the New Testament are very ordinary compared to the stories of Tibetan magic. [note: A good example of these accounts can be found in Keith Dowman, Sky Dancer (Snow Lion Publications, 1996)]. Perhaps the rarefied and pristine Tibetan landscape, high on the ‘rooftop’ of the world, contributed to a particularly vivid imagination. However it is just as likely that many of these alleged powers—what Indian yogis call siddhis—were in fact real on a physical level, perhaps made possible by the almost total lack of distractions in such a vast and barren landscape to interfere with the concentrative practices needed to develop such abilities. Tibetan monks have been called the ‘psychonauts’ of the inner world, as their environment was ideal for inner exploration and a significant percentage of their population became monks or nuns. It is likely that the ancient shamanic traditions also attained to equally pronounced accomplishments for similar reasons.

According to the records Milarepa was a good student and

learned the Black Arts well. When he had grown older he returned to the scene

of the crime, carrying the dangerous mix of magical skill and ill intent. He sought

out the greedy relatives and then manipulated certain ‘elemental keys’ (the

essence of ‘low magic’), which caused his uncle’s house to collapse during a

wedding celebration. Thirty-five people, all of whom were allies of the uncle

and aunt who had betrayed Milarepa’s mother, were crushed to death. According

to the legend some demons visited Milarepa and asked him if they should kill

the uncle and aunt also, to which Milarepa replied, ‘No. Let them live to know

my vengeance.’ Milarepa the sorcerer was not done, however. He later conjured a

huge hail storm that destroyed a vast swath of crops that belonged to a village

whose people had also been allied with Milarepa’s uncle and aunt.

According to the records Milarepa was a good student and

learned the Black Arts well. When he had grown older he returned to the scene

of the crime, carrying the dangerous mix of magical skill and ill intent. He sought

out the greedy relatives and then manipulated certain ‘elemental keys’ (the

essence of ‘low magic’), which caused his uncle’s house to collapse during a

wedding celebration. Thirty-five people, all of whom were allies of the uncle

and aunt who had betrayed Milarepa’s mother, were crushed to death. According

to the legend some demons visited Milarepa and asked him if they should kill

the uncle and aunt also, to which Milarepa replied, ‘No. Let them live to know

my vengeance.’ Milarepa the sorcerer was not done, however. He later conjured a

huge hail storm that destroyed a vast swath of crops that belonged to a village

whose people had also been allied with Milarepa’s uncle and aunt.

At this point Milarepa had, naturally, made many enemies. A number of them had put curses on him, and so he was being met by an oppositional psychic force that would begin to push him in the other direction, away from his dark path. More importantly, however, Milarepa carried the seeds of something great and noble within him. Consequently he experienced something that most criminals don’t—that being a burning remorse for his actions. Feeling a desire for atonement growing stronger and stronger, he decided to seek out a teacher who could guide him through the requisite purification that he would need were he to have any chance to avoid (as he believed) rebirth into the remedial hell realms, or as a lower life form (consistent with Buddhist theology).

He first went back to his original teacher who had taught him low magic, but this man recognized that he was not the one to perform the difficult task, and thus sent him on to a lama (‘teacher’) named Rongton Lhaga. This teacher was a renowned master of Dzogchen, one of the highest teachings within Tibetan Buddhism, reputed to be one of the ‘direct’ paths to enlightenment. After Milarepa found Rongton Lhaga, the lama gave him some instructions, but soon realized that he was not the right teacher either for this ‘terrible sinner’ (the words used by Milarepa when he had presented himself). He then told Milarepa to seek out a powerful master named Marpa the Translator who lived in the Lhobrak valley in southern Tibet. The lama added that Marpa and Milarepa had ‘karmic links from the past’ that made Marpa the appropriate teacher for him. When Milarepa heard the name Marpa the Translator he felt inexplicable joy, and knew that this would be his root guru who would be able to guide him to full awakening. (The deep passion that arose in him is reminiscent of the passion felt by a young Ramana Maharshi upon first hearing the name of the holy Mt. Arunachala that he was destined to spend his life at).

Marpa Lotsawa (1012-1097) was a Tibetan Buddhist master (and farmer) who had a reputation for being tough and disciplined. He had learned Sanskrit at a young age, and had subsequently traveled several times to India where he made lengthy stays, studying under his guru, the famed Indian master Naropa. (The first Buddhist university in America, founded in 1974 in Boulder, Colorado, was named after Naropa). Marpa brought back many Buddhist texts from India, translating them into Tibetan. He is usually credited with being the main transmitter of some of the most advanced teachings now found in Tibetan Buddhism, such as Mahamudra.

Marpa lived up to his reputation as a tough taskmaster, and

proceeded to subject Milarepa to an extended period of harsh and, at times,

openly cruel disciplines. Milarepa, convinced of the terrible karmic debt that

he needed to repay, surrendered to the treatment. One of the main devices Marpa

used was to instruct Milarepa to build a large stone tower. At the point of his

nearing completion with the back-breaking job, Marpa would assess the work, and

inform Milarepa that the tower was in the wrong place, and would need to be

torn down and built again. He had him do this several times—tearing down the

stone tower and building it elsewhere—in addition to other physical

deprivations. At other times Marpa would be drunk or pretending to be drunk, and

at times he would disclaim having given certain instructions to Milarepa the

day before. He also gave continuous false promises to give the teachings to

Milarepa and would constantly break those promises. In this way he put Milarepa

through not just great physical hardships but mental trials as well, especially

designed to test his faith. On top of all that, Marpa was physically abusive,

frequently beating Milarepa.

During the years of harsh labor and abuse Milarepa was not given any teachings

but functioned only as a servant. At one point, unable to bear Marpa’s

treatment any longer, he resolved to leave. Marpa’s wife, who took great pity

on him, forged a letter of introduction from Marpa to another lama not far away, who could teach

Milarepa. He went to this lama, but

after practicing his teachings for some time with no results, he admitted that

the introductory letter had been forged. The lama then sent him back to Marpa, explaining that the practices

were not working because Marpa had not blessed Milarepa’s presence with the lama. It seemed there was no way to

escape Marpa, and so Milarepa returned to him. But still Marpa would not teach

him. Finally driven to the point of deciding to commit suicide, Marpa relented

and began to instruct him.

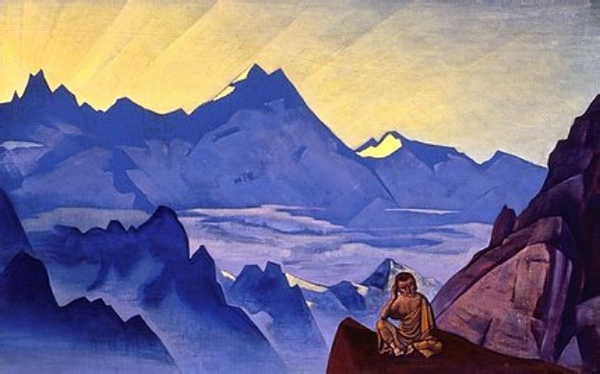

As Marpa explained, because Milarepa’s earlier crimes had

been so extreme he needed to go over the edge in order to be deemed worthy of

the gift he was seeking. The last of Milarepa’s powerful karmic residues had

been destroyed, and he was now an ‘empty cup’, ready to receive the higher

knowledge that would lead to his liberation. As might be expected, he excelled

as a student, progressing very quickly. After a while Milarepa retreated to the

mountains where he lived in seclusion, absorbed in deep meditation practice for

nine years. He dwelt in a frigid cave, but was given the psychic technique of tummo

(heat creation) which enabled him to withstand the cold. He was said to have

attained to the highest enlightenment. Many seekers of truth were drawn to him,

a number of whom became his disciples.

One of these disciples, the physician Gampopa, in turn became the teacher of

Dusum Kenpa, who was to be recognized as the first Karmapa, or ‘Black Hat

Lama’. This is the office of the continuously reincarnating master of the Karma

Kargyu lineage, the 17th incarnation of whom is alive today (in fact there are

currently two recognized 17th Karmapas in an unusual and somewhat

bizarre controversy that has been ongoing since the 1980s). The Karmapa is an

older lineage than that of the Dalai Lama (of whom the current one, Tenzin

Gyatso (b. 1935) is the 14th).

Teachings

Milarepa

also became a poet, and spontaneously composed over 100,000 lyric songs, the

manuscript of which exists today as The Hundred Thousand Songs of Milarepa.

Here is one of them, illustrating the classic Buddhist realization of shunyata

(‘emptiness’):

In the realm of

Absolute Truth, Buddha Himself does not exist.

There are no practices nor practitioners, no path, no realization,

and no stages, no Buddha’s bodies and no Wisdom.

There is then no

Nirvana, for these are merely names and thoughts.

Matter and beings in the universe are non-existent from the start; they have never come to be. There is no Truth, no Innate-Born Wisdom, no Karma, and no effect therefrom;

The World even has no name, such is Absolute Truth.

This is a very deep realization, possible only for one who has ‘gone beyond’. It is reminiscent of the 7th century Chinese Cha’an (Zen) master Hui-neng, who, seeing a few lines written by an advanced monk—‘The body is the tree of salvation/The mind is a clear mirror/Incessantly wipe and polish it/Let no dust fall on it’—famously countered with ‘Salvation is nothing like a tree/Nor a clear mirror/Essentially, not a ‘thing’ exists/What is there, then, for the dust to fall on?’

All fully awakened sages ultimately recognized the pure ‘emptiness’ of existence. ‘Emptiness’ in this context needs to be understood. It simply means that all things lack inherent and discreet existence—that is, all things are interdependent and in a state of flux, and thus the idea that a ‘thing’ can exist in and of itself (which naturally includes the ego) is ultimately an illusion. This is not the same as the Western idea of nihilism (although the two can be easily confused with each other). Nihilism involves a view that implies that existence has a lack of objective meaning, value, and overall purpose (the word comes from the Latin nihil, meaning ‘nothing’). Nihilism has become more relevant in current times, with our global population spike and advanced communication technologies, making information in general more accessible. That in turn has many side-effects, some of which are increased doubt, cynicism, sarcasm, and a general loss of a sense of the sacred.

Seeing into the illusoriness of the existence of discreet objects (and the personal self) does not negate meaning or value, but is rather a pointer toward something of such profundity that our conventionally conditioned minds need to be de-conditioned in order to begin to recognize it. Nihilism is all too often used as a disguise for fear of life, or unwillingness to be responsible for oneself. The insight of Milarepa or Hui-neng is much deeper than mere nihilism and only comes after years of committed practice and relentless willingness to deconstruct the false self and see deeply into the nature of Reality.

In the passage quoted above, Milarepa is not actually saying that nothing per se exists, he is pointing to the understanding that prior to full awakening, we see everything through the filter of deluded concepts. We do not see Reality, but only our ideas of it (including ‘spiritual’ ideas, which can prove to be some of the most stubborn illusions). When we remove the filters of ego-based projection—that is, the delusion of duality—the world is revealed to be something far beyond the world we’ve constructed with our minds. In fact, Milarepa, despite his deep insight into Reality and his ascetic nature (living in caves for many years) had a great love for the play of existence, and the vividly beautiful landscape he dwelt in. He once expressed it thusly:

Beneath the bright light in the sky, stand snow mountains to the North.

Near these are the holy pasture lands, and fertile Medicine Valley.

Like a golden

divan is the narrow basin, round it winds the river, Earth’s great blessing.

When one approaches closer, one sees a great rock towering above a meadow.

As prophesied by Buddha in past ages, it is the Black Hill, the rock of Bije Mountain Range.

It is the central place, north of the woodlands on the border between Tibet and India,

where tigers roam freely.

The medicine trees, Tsandam and Zundru, are found here growing wild.

The rock looks like a heap of glistening jewels…

One can see that those are not the words of a ‘nihilist’. Like some of the Japanese Zen haiku poets (such as Basho), Milarepa combined a radical insight into Being with the realization that the universe of form was one and the same as formlessness. As the famous Buddhist Heart Sutra expresses it, ‘Form is Emptiness, and Emptiness is Form’. Milarepa wrote,

Thunder, lightening, and the clouds,

Arising as they do out of the sky,

Vanish and recede back into it.

The rainbow, fog, and mist,

Arising as they do from the firmament,

Vanish and recede back into it.

Honey, fruit, and crops grow out of the earth;

All vanish and recede back into it…

Self-awareness, self-illumination, and self-liberation,

Arising as they do from the Mind-Essence,

All vanish and dissolve back into the mind…

He who realizes the nature of the mind,

Sees the great Illumination without coming and going,

Observing the nature of all outer forms,

He realizes that they are but illusory visions of the mind.

He sees also the identity of the Void and the Form…

Discrimination of ‘the two’ is the source of all wrong views.

From the ultimate viewpoint there is no view whatsoever.

Mahamudra is the name of the teaching that Milarepa transmitted, from his guru

Marpa, to some of his own students (such as Gampopa). The word means ‘great

seal’, but has a deeper meaning, denoting the experience of Reality—vividly,

and beyond all mental distortions—as had by one who has mastered it. What

Mahamudra points toward is both profound and simple, the essential paradox that

all deeply realized sages embody and teach. It is profound because our minds

are deeply mired in the illusion of duality (the experience of separation and

disconnection), and so a teaching pointing toward non-duality seems impossible

to fully realize. And it is simple because nothing, in the final analysis, could

possibly be more simple than non-duality.

The basis of the realization of Mahamudra is in recognizing the ‘gap’ of non-dual wisdom that is naturally present between all thoughts. Normally we remain unaware of this ‘gap’, because we are too identified with our thoughts, and in particular, with the ‘self’ we take ourselves to be, who is apparently having these thoughts. Between the sense of ourselves as a particular ‘me’— with all my attendant dramas and stories and dreams and fears, and so on—and the endless display of the thoughts themselves, it’s no small wonder that we simply fail to notice the vast and pure ‘background’ or ‘space’ within which all our mental activity is arising.

Milarepa compared the endless display of the mind, and the experiences it produces, to a ‘morning mist’, and said that trying to hold onto the mist is pointless. Our task is always to return our bare attention to the reality of space—that is, the space between thoughts, which is in fact the vastness of pure potential energy. To even call this ‘space’ is inadequate as no concept can capture it or adequately define it. Even to refer to it as ‘it’—a necessary utility of language—still misses the point, because this ‘it’ is in fact our own real nature.

According to the legends, Milarepa spent a

number of years wandering the lands after his enlightenment, teaching whenever

the occasion presented itself. During parts of that time he was said to subsist

on an extreme ascetic diet that consisted largely of Stinging Nettle tea, which

caused his skin to take on a green tinge. This is why many of the Tibetan tangka (religious painting) renderings

of him show him with a greenish skin. However one takes a legend like that—and

it probably is at least partly true, as Tibetan and Indian wandering mystics

have long been famed for extreme ascetic practices—it is a fitting metaphor for

what a figure like Milarepa embodies: fierce and unrelenting commitment.

Milarepa is the classic example of totality of action. Whatever he did, he went

all out at (a common trait of one destined to become a great sage). Marpa had

nicknamed him ‘Great Magician’ because of his (deadly) proficiency in that

area. When serving as Marpa’s slave for several years, he gave that his all.

And in studying and practicing the dharma, he again was full-on, with the

result being that he was said to attain to the highest realizations in the

shortest time ever known in his particular tradition.

According to the legends, Milarepa spent a

number of years wandering the lands after his enlightenment, teaching whenever

the occasion presented itself. During parts of that time he was said to subsist

on an extreme ascetic diet that consisted largely of Stinging Nettle tea, which

caused his skin to take on a green tinge. This is why many of the Tibetan tangka (religious painting) renderings

of him show him with a greenish skin. However one takes a legend like that—and

it probably is at least partly true, as Tibetan and Indian wandering mystics

have long been famed for extreme ascetic practices—it is a fitting metaphor for

what a figure like Milarepa embodies: fierce and unrelenting commitment.

Milarepa is the classic example of totality of action. Whatever he did, he went

all out at (a common trait of one destined to become a great sage). Marpa had

nicknamed him ‘Great Magician’ because of his (deadly) proficiency in that

area. When serving as Marpa’s slave for several years, he gave that his all.

And in studying and practicing the dharma, he again was full-on, with the

result being that he was said to attain to the highest realizations in the

shortest time ever known in his particular tradition.

A sage like Milarepa teaches us the supreme value of cultivating passion for awakening above all else; and that in doing so, it becomes possible to reverse even the darkest of fortunes.

___________________________________

Hakuin: Zen Executioner

Hakuin Ekaku (1686-1768) is generally recognized as the most

important Japanese Zen master of recent centuries.5 He was born

Nagasawa Iwajiro (in Japan, the family name precedes the first name) on January

19, 1686, near Mount Fuji, the youngest of five children. From an early age his

inclination toward the spiritual life was clear. He was ordained a Zen monk at

just 15 years old. The seeds of his desire for awakening originated, in part,

from a natural sensitivity and a type of psychological trauma he passed through

at age 11. He had been listening to a Buddhist priest of his mother’s faith

(the Nichiren Buddhist tradition) give a lecture on the ‘hell realms’ of the

afterlife, when he became caught in the throes of a deep and overwhelming fear.

Determined to overcome this fear (note the striking similarity with Ramana

Maharshi’s story, below), he decided to totally commit himself to the Buddhist

path, and began even at that young age to practice some basic spiritual

austerities (such as waking early, reciting prayers, performing prostrations,

reading scriptures, and so forth). These practices had limited effect, and so

Iwajiro decided his only hope to conquer his deep fear of a hellish afterlife

was to become a Buddhist priest.

Hakuin Ekaku (1686-1768) is generally recognized as the most

important Japanese Zen master of recent centuries.5 He was born

Nagasawa Iwajiro (in Japan, the family name precedes the first name) on January

19, 1686, near Mount Fuji, the youngest of five children. From an early age his

inclination toward the spiritual life was clear. He was ordained a Zen monk at

just 15 years old. The seeds of his desire for awakening originated, in part,

from a natural sensitivity and a type of psychological trauma he passed through

at age 11. He had been listening to a Buddhist priest of his mother’s faith

(the Nichiren Buddhist tradition) give a lecture on the ‘hell realms’ of the

afterlife, when he became caught in the throes of a deep and overwhelming fear.

Determined to overcome this fear (note the striking similarity with Ramana

Maharshi’s story, below), he decided to totally commit himself to the Buddhist

path, and began even at that young age to practice some basic spiritual

austerities (such as waking early, reciting prayers, performing prostrations,

reading scriptures, and so forth). These practices had limited effect, and so

Iwajiro decided his only hope to conquer his deep fear of a hellish afterlife

was to become a Buddhist priest.

When he was 14, his parents, realizing their young son could not be dissuaded from his chosen path, took him to a local temple, which in turn sent him right away to the Daisho-ji temple in a nearby town. He spent the next few years at this temple undertaking novice duties, serving as attendant to the resident priest and being schooled in the classical Chinese language (necessary for any serious Japanese Buddhist, as Buddhism had been transmitted to Japan from China around the 12th century CE, and many important texts were in Chinese).

At this early age Iwajiro had become acquainted with the famous Buddhist scripture known as the Lotus Sutra, but he did not have a high opinion of it. Years later he would return to that particular scripture during the episode of his ‘final awakening’ in which its teachings became crystal clear to him. He had originally dismissed the Lotus Sutra for its seeming simplicity, but it was this same simplicity that he would later understand as profound wisdom. The association between ‘seeming simplicity’ and deep wisdom is a common one in the enlightenment tradition. ‘Seeming simplicity’ in this case means a clear, straightforward view of reality—what typically is obscured by the workings of the mind in its commonly deluded state. Meditation and radical insight are the practices of clearing away the clouds of delusion and illusion, revealing the pristine nature of reality.

At 18 Iwajiro transferred to a different temple, where he was to begin his formal training as a monk. At this temple he underwent a phase of alienation from Zen Buddhism brought on by two main issues: first, his disappointment that the training at the temple appeared to be more academic than experiential (the monks were mainly involved in studying Chinese Zen poetry); and second, his learning about a famous Zen master who had been killed by bandits, and seemed to die in a manner that lacked the dignity of an awakened being. Iwajiro concluded that if a great Zen master could die in such a manner, then he himself would have little hope of conquering his fear of the hell-realms that he still carried within.

Rejecting Zen practice for now, he decided to give himself over to the study of literature and the arts (including calligraphy, which he would become an accomplished master of). The next year he transferred to another temple, one that had a large library. Here he haphazardly discovered a particular book that made mention of an ancient Chinese master who emphasized the need for great effort in order to break free of the mind’s laziness and delusions. As it happened, this Chinese master had revived a particular lineage, the Lin-chi, that Iwajiro himself would later revive in Japan (a tradition now known as Rinzai, one of the two main lines of Japanese Zen).

Shortly after, Iwajiro embarked on an extended pilgrimage for several years, during which he wandered over many parts of Japan. The main criticism he had developed by then of the existing Zen tradition was that it was dominated by too much passivity—the word he used is sometimes translated in English as ‘quietist’—an approach that he believed tended to ruin the drive, focus, and tenacity he had determined by then was necessary for deep awakening. He himself, by his own admission, had not yet passed through the profounder awakenings, so at this point his views were speculative and intuitive.

By 23 years of age, Iwajiro had grown increasingly skeptical of the various Zen teachers and authorities of his time, and had decided to give himself over to intensive sitting meditation practice (zazen) focusing mostly on a particular ancient koan. (A koan is a rationally insoluble problem—such as ‘what is the sound of one hand clapping?’—that is designed to quiet the part of the mind that tries to figure things out in a superficial way. The result, if achieved, is a breakthrough in insight that goes beyond the standard rational approach to problems. A koan successfully ‘solved’ leads to mystical realization; that is, a sense of deeper connectedness between self and universe. The depth of this realization can vary greatly, but generally speaking it is a temporary affair that does not significantly transform more entrenched elements of character. Deeper follow up work and practice is almost always required).

After considerable effort he experienced a breakthrough in realization (typically called kensho or satori in Zen—with the latter denoting a somewhat more prolonged or profound awakening), something he felt quite ecstatic about. Because he was working without guidance, however, coarser elements of his ego had not yet been worn down. He had already been given to some intellectual arrogance before (common with the exceptionally bright), and the satori (as it will often do) simply highlighted that part of his character more clearly. He later wrote of this period that he was ‘puffed up with soaring pride, bursting with arrogance’.