(The following is an abbreviated version of Chapter Two from my book The Inner Light: Self-Realization via the Western Esoteric Tradition (Axis Mundi Books, March 2014), available on Amazon and select bookstores.

Introduction to Psycho-Spiritual Alchemy

Aurum nostrum non est aurum vulgi (our gold is not ordinary gold).

—Gerhard Dorn

The key to alchemy is found in the word transmutation, a word that in its original Latin meaning refers to total change. Physically this denotes a change of the properties of matter, and thus of substance; psycho-spiritually, it refers to inner transformation—in specific, certain actions to aid in freeing the spiritual essence that is ‘trapped’ within (echoing the Gnostic view that spirit is trapped in matter). This idea had its basis in the ancient belief that within the Earth ‘grew’ metals and that, given enough time, these metals would ultimately become gold. Nature was seen as fundamentally engaged in a process of evolution, and the essential idea of alchemy was to speed this process up—in short, to save time.

Spiritual alchemy is concerned with the transmutation of the personality and its structures, so as to allow for the light of unobstructed consciousness and pure Being to be directly known. The direct knowing of pure Being is gnosis, Self-realization. Spiritual alchemy is thus a means by which we re-structure our personality and the various levels of our identification with it, so as to realize the infinite potential of our true being. It is essentially a comprehensive roadmap, using colourful and sophisticated symbols, detailing the means and steps by which we get ourselves ‘out of our own way’ and allow our highest and best destiny to unfold.

The main difference between spiritual alchemy and alchemy as merely a primitive proto-science—the supposed precursor of modern chemistry—is that the former involves an interdependent relationship between the subject (self) and the object (all that is not-self). In materialistic science the subject is the observer distinct from what he or she studies (the object). In spiritual alchemy this distinction is much less defined, because the transformation of the subject, of the personality, is pre-eminent.

A key point found repeatedly within alchemy is the idea that the alchemist can only succeed in his work if he approaches it with purity of intent, with a heart free of ulterior agendas (an idea that was mirrored in the Grail myths, where only a knight of pure heart had any hope of finding the Grail). This idea was emphasized by some early scribes who noted with irony that alchemy was notorious for its failed alchemists, i.e. those who sought alchemical success in elaborate and expensive laboratory attempts to create gold but often ended up broke in the process.1 The esoteric foundation of spiritual alchemy is found in the ancient world-wide myths that deal with the life, death and resurrection of a god. The candidate or initiate is to undergo a similar process, in order to awaken to their divine condition—a type of radical deconstruction and ‘rebirth’. This process involves a number of stages, to be summarized below. Before detailing these stages it is useful to have some grasp of the history of alchemy, as well as some of the most basic features of its esoteric foundation.

Background

Historically, there are generally recognized to be three main lines of alchemy: Chinese, Indian, and Western. All three appear to have developed some time during the first few centuries BCE, though evidence at present favours the Chinese version as the oldest.2 Traditionally, alchemy has been associated with two main activities: the attempt to manufacture gold (or silver) from baser metals; and the attempt to create an elixir of sorts that when ingested would result in great vitality and health, and possibly even immortality. Chinese and Indian alchemy was concerned at times with producing gold, but more commonly the focus was on the creation of the magical elixir that could, it was believed, produce great powers and everlasting life.

Western alchemy in all likelihood had its origins in the early work of goldsmiths, miners, and metallurgists, especially those of ancient Egypt.3 This form of alchemy, perhaps reflecting the natural inclination of the Western mind toward extroversion and materiality, was ultimately concerned more with the idea of the ‘Philosopher’s Stone’, the name given to a substance that could transmute base metals, like lead, into gold. Over time the psycho-spiritual component of alchemy began to develop, possibly in Alexandria, in the early centuries BCE. As with so many elements of the Western esoteric tradition Western alchemy finds many of its roots in the ideas of the ancient Greeks, ideas that were given coherence most notably by Plato and Aristotle. By the time of the early centuries after Christ it had evolved into a specific practice (both a ‘science’ and an ‘art’ in the wider definition of those terms), tailored toward creating change both internally and externally.

Both Eastern and Western alchemy have a psycho-spiritual esoteric component based on the essential idea of inner transformation. The material dimension of alchemy may have been concerned with such matters as immortality of the body or the production of gold, but from the esoteric perspective these were ultimately not separate from the Great Work of inner transformation. Because alchemy was influenced by initiatic streams of thought (arising from Taoism and Tantra in the East, and Hermeticism and Gnosticism in the West) it was eventually understood, by at least some alchemists, that the practical laboratory work was not separate from the inner processes of transformation undergone by the alchemist. This was consistent with the idea of the essential interconnection between mind and matter perhaps best summarized by the Hermetic maxim ‘as above, so below’. It is a given that not all alchemists were concerned with inner transformation, that many were largely concerned with the pursuit of dreams of wealth and power. But it is also clear that alchemy through the centuries preserved many of the mystery teachings, including elements of Gnosticism that were suppressed or exterminated outright by the rising power of the Church after the 4th century CE.

The focus of this chapter is mainly on Western alchemy and in particular its psycho-spiritual dimension.4 The English word ‘alchemy’ has uncertain origins, but is sometimes thought to stem from the Arabic al-khimia, possibly deriving from the Coptic word kem, which means ‘black land’, another name for Egypt. Thus ‘alchemy’ may have originally meant ‘of Egypt’. The black land refers to the soil around the Nile valley, which was rich with nutrients when the waters of the Nile would recede after the annual flooding. An alternate view holds that the Chinese word kim—which refers to the production of gold— migrated to the Middle East where it became the word kem, and later, al-khimia.

Western alchemy as a specific practice appears to find its origins on the coast of northern Egypt in Alexandria, that extraordinary city founded around 330 BCE by Alexander the Great. With the ascent of Christendom and the decline of Alexandria (including the gradual destruction of its famous library in a series of calamities), alchemy gradually faded from view in the West, but it did not die out entirely. It was, instead, taken up by the Arabs (themselves the conquerors of Egypt), and later by Jabir ibn Hayyan, an 8th century Persian magus whom some regard as the prototypical alchemist. (Identifying the authors behind early alchemical writings has been notoriously difficult, as a standard practice was to ascribe such works to important figures or even gods such as Hermes, but most scholars accept the legitimacy of Jabir’s name and legacy).5

Modern science tends to view early alchemy as largely the primitive proto-science that morphed into chemistry around the 17th century via the efforts of Robert Boyle and others. There is of course some truth to that. By the 17th century alchemy had been largely abandoned as a laboratory ‘science’, but its esoteric side was preserved, if only marginally, and discussed in various occult circles of the 18th and 19th centuries. In the popular domain it was C.G. Jung who, in the early 20th century, largely rescued alchemy from the dusty pages of forgotten library archives by wedding much of its rich symbolism to his theory of analytical psychology. Some esoteric scholars such as Julius Evola took exception to Jung’s efforts, believing it to be a kind of debasement of the deeper meaning of the Great Work. In Evola’s view, alchemy is a path of spiritual awakening that is intended only for psychologically integrated individuals, and is not a symbolic description of the process of becoming psychologically integrated (what Jung called ‘individuation’).6 Evola, along with other Traditionalists such as Rene Guenon, made determined attempts to preserve the sanctity of the esoteric path against what they saw as the vulgar, simplified world-views of our modern materialistic times, and it is not hard to find sympathy for their positions if one takes the time to reflect on some of the side-effects of the scientific revolution and industrial age. But the fact remains that the average modern day ‘truth-seeker’ is rarely a psychologically integrated individual in the ideal sense, and almost always needs to do considerable psychological healing prior to, or alongside with, more rarefied spiritual practices (such as, for example, simple sitting meditations). Thus from a practical point of view it is more than a matter of merely finding sympathy for Jung’s work and related psycho-spiritual interpretations of alchemy, it is a matter of recognizing the value and usefulness of such approaches for current times.

The Inner Science of Alchemy: the Philosopher’s Stone and Gold

The Arabic term al-khimia also means ‘the art of transformation’, and this applies to both physical levels (thus being the basis of the later science of chemistry) in which the alchemist of old was interested in transforming base materials, like lead, into more exalted materials such as gold, as well as to the inner practice of alchemy, which involves the transformation of the individual from unconscious ‘raw material’ to the ‘finer material’ of self-realization and divine illumination. It is this latter science of alchemy, the inner art of transformation, that we are mainly concerned with here.

The prized goal of alchemy, in the more traditional sense, was the substance known as gold (and, on occasion, silver). Gold has some interesting chemical properties—it is the most ductile of all metals, meaning, it can be reshaped into endless forms without fracturing. It is also largely immune to most corrosive agents of air or water, and resistant to corruption by fire (which is why it was always valued in making jewellery). Thus its great strength, and brilliant color, makes it a powerful symbol for that which is both radiant and indestructible within us, i.e., our highest nature and true inner self.

However, according to alchemy, the manufacture of gold was possible only via the medium of the philosopher’s stone. When this latter was applied to base metals, then the transmutation, resulting in gold (or silver) allegedly could happen. On the level of psycho-spiritual symbolism, the formula…

Base metal (such as lead) + Philosopher’s Stone = Gold (or Silver)

…has not always been fully understood (and on the physical level, never conclusively proven to have been achieved). Typically, the end result (gold or silver) has been thought to represent the awakened self, but it is more technically correct that the Philosopher’s Stone is the awakened self. The gold or silver represents the transformation of one’s world, or the manifestation of one’s higher desires. The essential relationship between the two (Philosopher’s Stone and gold) is crucially important because they are ultimately interdependent. That is, transformation of self really only works when we also have an intention to transform our outer world, i.e., shine the light of our being outward in order to realize our highest callings in life.7 In other words, self-realization without involvement in the world (in some fashion) is incomplete.

The Materia Prima and Solve et Coagula

Alchemy posits that all things in the universe originate with the materia prima (First Matter). The idea of the ‘primal material’ was developed by Aristotle and refers to the idea that there is a primordial matter that lies behind all forms, but that is itself invisible. It is the womb of creation, the field of pure potentiality, but it only gains existence, in the strictest sense, when given form. In the alchemical process, the primal material is that which remains when something has been reduced to its essence and can be reduced no further. Psychologically, this is a potent symbol for the inner process of transformation in which we regularly arrive at ‘core realizations’ that cannot be deconstructed further, but that themselves become the ground for successfully moving forward in life—‘integrating’ as we evolve.

The alchemists of old believed that any given base metal must first be reduced to its materia prima prior to it being transmuted into gold. The psycho-spiritual symbolism here is straightforward. It points to the de-conditioning process that lies at the heart of spiritual transformation—that is, the deconstructing of that which is false about us, to reveal that which is true and real, i.e., our divine self. This ‘deconstruction’ was typically likened to a ‘mystical death’, or the reduction to formless chaos, often represented by aquatic symbols, sometimes expressed as ‘perform no operation until all be made water’. It denotes the necessary abandoning of the past, the ‘death’ of the initiate’s false self, prior to their rebirth or re-awakening to their higher self.8 In mystical Christian symbolism this was all symbolized by the crucifixion and resurrection, an echo of older pagan myths that generally involved the death and reconstitution of a god.

The process of deconstruction can also be seen as a constructive process, and in some Hermetic schools of alchemy that is how they saw it—the physical body, being associated with Saturn (or lead) being transmuted into the ‘solar body’, or gold. Various world esoteric traditions make reference to this idea of a ‘body of light’ that is attained only through deep and profound practice. The Bible seems to point to it in Matthew, 17:1-2, in what has come to be known as the transfiguration scene:

And after six days Jesus taketh Peter, James, and John his brother, and bringeth them up into an high mountain apart,

And was transfigured before them: and his face did shine as the sun, and his raiment was white as the light.

Ultimately, whether we choose to see the process of transformation as deconstructive (dissolving the ego impurities) or constructive (transforming and thus heightening our ‘vibration’ so that we attain a more rarefied consciousness) is more a matter of perspective, and less important than actually engaging the work. But in point of fact, the process of alchemy actually involves both of these actions, through what is referred to as solve et coagula — the dissolution and coagulation — the deconstruction and re-construction of our personality. Or put more simply, to separate and recombine. There is a clear and interesting symbolic parallel here in the Egyptian myth of Osiris, who is killed by his brother Set, has his body dismembered, and then is reconstructed by the gods Isis and Thoth as part of his resurrection in the duat (Otherworld)—a symbolism that is pure alchemical solve et coagula. It defines the heart of the spiritual process of ‘breaking down’ and being ‘reborn’.

In alchemy, as in all forms of Hermetic High Magic as well as the Tantric schools of India and Tibet, matter, or the physical universe, is not seen as separate from the mind, or spiritual realities, but is rather recognized as a reflection of it. The Magnum Opus or ‘Great Work’ of alchemy is ultimately to realize the fundamental interrelationship between mind and matter, between self and world, between heaven and earth, finally ending in the non-dual realization (All is One). However—and this is a crucial point—the apparent dualism of existence is not to be denied or glossed over out of fear of embracing its lessons. Rather, duality is to be embraced (and even celebrated) as the means by which we uncover key realizations about our inner nature. Alchemy is all about altering time, that is, the natural evolution of things, so that we can pass through our essential lessons quicker. But it is not about denying these lessons, nor the joys and struggles of independent selfhood.

Although an alchemist was typically thought to be someone who worked to transform physical metals to gold only, in the hope of striking it rich (and many did attempt that mundane approach), it was in fact the alchemist’s spiritual transformation that was supposed to precede his work with physical materials—or at the very least, to accompany it. This idea applies equally in current times to the so-called arts of manifestation. All our efforts to apply change to our lives via manifestation practices amounts to little if we are not first seeking to change ourselves for the better.

Psycho-spiritual alchemy is ultimately not about manipulating reality. It is an ancient system of psychology in which the alchemist seeks to confront and understand his or her own mind and soul, so as to pass through a deep transformation and emerge free of the limitations of the personality. Like all traditions, it suffered corruption over time and distorted versions gradually formed. These corrupted versions are more concerned with the manipulation of external events (control)—much as corrupted versions of science and business exist in current times in the form of those who use science or commerce to further selfish agendas. However the deeper esoteric work of the alchemist was always about personal awakening and union with the divine mind or higher self, much as the true higher purpose of science or business is about increasing both well-being for self and well-being for others (‘win-win’).

This inner awakening is given priority, and then leads naturally to the transformation of our world—much as the alchemist first transforms him or herself, and then seeks to transform the outer world, or how the mage first awakens the inner higher self, and then interacts with the more elemental energies and spirits. The idea was well illustrated in a Chinese fable once relayed by Richard Wilhelm, concerning a Taoist monk and a Chinese village suffering the effects of a prolonged drought. The village councillors, desperate for rain, sought the aid of the monk to bring about rain by some ‘supernatural’ method. The Taoist simply asked for a private room and shut himself in for three days. At the end of the third day, rain fell. The monk emerged from his room, whereupon Wilhelm asked him what he had done. The monk replied that prior to visiting the town he had been merged with the Tao. When he arrived in the town, he was not connected to the Tao, but after three days of meditating in the room, he was once again merged with the Tao. He then added that it would be natural for that which was around him (the immediate environment of the town) to also be in Tao.

The very idea is the essence of alchemy and the core principle of Hermetic wisdom (‘as above, so below’), meaning that in aligning ourselves with the Higher principles, we aid in causing changes around us that follow suit. As we uncover the light within, so we aid in bringing light to our surroundings.9

Some Basic Alchemical Principles

As mentioned, alchemy essentially begins with the idea of the Prime Matter (materia prima). This Prime Matter was believed to have a basic fourfold structure, known as the four basic classical elements—usually recognized as fire, water, air, earth. A fifth ‘element’ has been commonly recognized as well, variously called ether, space, quintessence, or spirit. The idea of these basic elements goes back to ancient Babylonia (the Enuma Elish, the chief Babylonian Creation myth, written circa 1700 BCE, made mention of them). It fell to the Greek pre-Socratics, in particular Empedocles (circa 490-430 BCE), to elaborate on the idea, although it was Plato (424-348 BCE) who first used the term ‘elements’ (from the Greek stoicheion), and Aristotle who fleshed out the scheme.10 Empedocles had been influenced by Pythagoras and certain esoteric schools such as the Orphic mysteries, but appears to have developed his independent view of things. His idea of the four basic elements was part of his attempt to explain how things come to undergo change, the understanding of which lies at the very root of alchemy. Empedocles held that all of existence is a process of change via the separation and combination of different elements. Things do not, he maintained, change by passing from existence to non-existence (as Heraclitus had held), but rather via the process of the mixing, dividing, and the re-combining of different combinations of substances and their elemental properties.

An essential idea behind most esoteric tradition, never to be lost sight of, is that this material reality we dwell in is a degraded copy of a finer, more subtle and rarefied, dimension. Much of Plato’s highly influential cosmology was based on this idea, and even Empedocles asserted it in reference to the basic elements, declaring, ‘from them, flow all things that are, or have been, or shall be.’11 For him, these elements represented phases of transition, a crystallization of subtle energies into material form. In short, the ‘Supreme Being’ imposed a fourfold structure onto the Prime Matter, in order to condense the subtle into the material, and thereby create the material universe. Such ideas are seen by historians of science as primitive scientific glimmerings (for e.g., complex elements arising from simple elements, as the result of a star going nova), but they are perhaps more valid when understood as esoteric teachings that are central to an understanding of psycho-spiritual alchemy. Elements of the personality are to be restructured, made concrete, if you will, so that they can be recognized and thereby transformed. In so doing, the personality becomes more capable of supporting the growth of higher potentialities, and the emergence of the higher self.

According to the early alchemists, the four elements—fire, water, air, and earth—come into existence via the combination of specific qualities, recognized as hot, cold, wet, and dry, being ‘impressed’ on to the Prime Matter. For example, when hot and dry are impressed on the Prime Matter, we have fire; if cold and dry, then earth; if wet and hot, then air; if cold and wet, then water. When these qualities are changed, the elements themselves are changed. A few examples will suffice:

1. Add water to fire (substituting wet for dry; hot and dry becomes hot and wet: steam, or air).

2. Add fire to water (substituting hot for wet; cold and wet becomes hot and wet: steam, or air). This is known as vaporization, which can occur via boiling or evaporation.

3. Add cold to air, and air will ‘become’ water (substitute cold for hot; wet and hot becomes wet and cold; air becomes water). This is known as condensation.

And so forth. Modern chemistry is obviously vastly more comprehensive in its grasp of such matters as pertains to physical reality—the modern table of elements, or Periodic Table, recognizes (as of this writing in 2012) no less than 118 isolated elements, a far cry from the four or five of Empedocles, Plato, and Aristotle—but when the esoteric basis of alchemy is understood, it is also understood to be addressing a domain utterly distinct from that addressed by modern chemistry.

What follows is a brief synopsis of the esoteric significance of the five elements:

Fire: In esoteric studies all elements carry great significance, but in the realm of alchemy, it may be said that fire rules. It is the key, the mastery of which has long been held to be of prime importance by alchemists and shamans of old (as well as by smiths and potters, craftsmen whose work was related in many ways to alchemy). This is because fire is the element of transmutation par excellence, the key to changing things from one state to another—beginning with the most obvious examples of the power of the Sun and the core of our planet to heat the surface of the Earth, allowing for the possibility for life as we know it to develop.12 Of the four qualities mentioned above—hot, cold, wet, and dry—only two, hot and cold, are foundational (being found in space beyond our planet), and as cold is but the absence of heat, in the final analysis only fire (hot) is the essential transformational force. As Titus Burckhardt put it.

It is the effect of fire alone that renders the substance in the alchemist’s retort successively liquid, gaseous, fiery, and once again solid. Thus, it imitates in miniature the ‘work’ of Nature herself.13

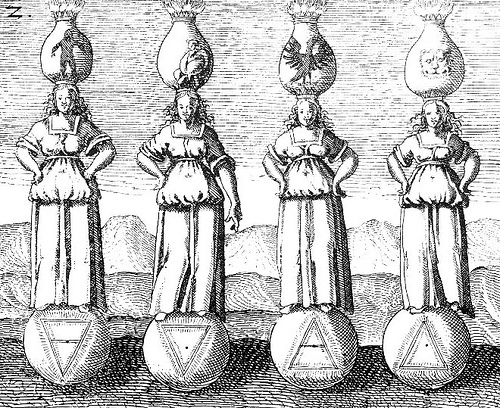

In alchemy, fire is traditionally associated with the color red, with the qualities of hot and dry, and the force that rarefies and refines things, as well as causing total transformation. Psychologically, fire is usually connected to will, energy, and sometimes intuition. (On occasion it is connected to feeling, although this latter is more often associated with the water element). Alchemically, fire is symbolized by a triangle with the apex pointing up. In terms of geometry, the Platonic solid that is connected to fire is the tetrahedron, or four-sided pyramid. (The idea of Platonic solids corresponding to the four elements derives from Plato, although it was earlier Greeks who discovered the shapes of the actual Platonic solids. Plato’s scheme is subjective and rather contrived; it is included here more as a historical curiosity. He considered that fire was ‘sharp’, rather like the four-sided pyramid).

Water: Water is traditionally connected to the color blue, and to the qualities of wet and cold. It is a potent symbol in physical reality and for life in particular, as the planet we live on and the bodies we inhabit are primarily water. Water is the great dissolver and the womb for creation. Psychologically it is usually associated with feelings and emotions. In the symbolism of alchemy, it is represented by the triangle with the apex pointing down. The Platonic solid for water is the icosahedron (a solid with twenty sides, closest of the five solids to resembling a ball, and thus most similar to the ‘smoothness’ and ‘slipperiness’ of water).

Air: Air is traditionally connected to the color yellow, and to the qualities of hot and wet. Air is a natural purifier, rendering the coarse more fine, and enabling the subtlety of mind that allows for clearer understanding. Accordingly, air is the element of thinking and reason. Its alchemical symbol is the right side up triangle with a horizontal line running through it. The Platonic solid for air is the octahedron (eight-sided solid).

Earth: Earth is the element traditionally associated with the color green (and sometimes black), and with the qualities of cold and dry. It is the symbol for all matters pertaining to the physical and the practical. Its symbol is the upside down triangle with a horizontal line bisecting it. The Platonic solid is the cube (six-sided solid, its square solidity making it a natural symbol for the solid Earth that supports us).

Quintessence (or Spirit, or Ether): The word ‘quintessence’, which literally means ‘fifth element’, is beyond the four basic elements as such. Aristotle described it as being beyond the ‘sub-lunar sphere’ and as being the basic material of the immortal and incorruptible ‘heaven realms’, free of any of the four qualities and incapable of change. However, later philosophers and alchemists granted this mysterious element certain qualities, such as those of ability to change density, or subtleness beyond that of light itself. There are grounds for speculating a link between this enigmatic ‘fifth classical element’ and the ‘dark matter’ currently studied by modern physicists, but that is highly speculative. Quintessence, or ‘ether’ as it also has been known, is sometimes linked to the concept of empty space. Its symbol is generally a circle with eight spokes, and its Platonic solid is sometimes considered the dodecahedron, the twelve-sided solid, although Aristotle resisted this latter association.

The Three Great Principles

In the early 1500s the Swiss alchemist Paracelsus, inspired by the earlier Sufi alchemist Jabir ibn Hayyan, decided to develop the old Greek notion of the five elements, introducing the idea of the three basic alchemical principles, those being sulphur, Mercury (a.k.a. quicksilver), and salt, representing spirit, soul, and body, respectively. Much as with the four basic elements, these three do not refer to the actual physical forms of sulphur, mercury, and salt, but rather to the various processes and stages of alchemical transformation that they represent. It should also be noted here that it is easy for the casual researcher of these matters to become confused, as it is uncommon to find any two ‘authorities’ on alchemy agreeing completely on the respective symbolic meanings of sulphur, mercury, and salt. What follows is the broadest consensus of the views of a number of scholars and historians.

Sulphur: According to Paracelsus’ original teachings on the three principles of alchemy, sulphur was considered to be ‘that which boils’, or oil, and thus the aspect of unctuousness. Psycho-spiritually it symbolizes the immortal Spirit, or pure consciousness. It is generally connected to the solar and masculine principles, and symbolically to the lion.

Mercury: Mercury, also known as quicksilver, is the volatile quality of transformation, representing that which arises as a fume. It is symbolic of the vital spirit or soul, or what is sometimes called the life-force, known in various traditions by such terms as ruach, prana, or Shakti (and hence its natural connection to the breath; see Chapter Five: The Astral Light, for more). As an energetic principle it is considered to be connected to both blood and semen, key substances associated with the vital spirit or life-force. It is sometimes symbolized by the griffon, and is generally associated with the lunar and feminine polarity. (Although, paradoxically, it is also occasionally viewed as hermaphroditic in nature). It is that which unites Spirit and the worlds of material form. Some authors seem to confuse Mercury with Spirit, probably because one of the terms for the life-force is ‘vital spirit’, deriving from the Latin word for breath, spiritus.14

Salt: In alchemy, salt represents the physical foundation, and may be thought of as the body in its corrective state. It is what remains from the transformational process, the ‘ashes’. It serves to ‘ground’ the volatile ‘spirit’. As with so many alchemical symbols, the meaning is at times ambivalent and seldom universally agreed on. For example, C. G. Jung, drawing from the Turba Philosophorum (a medieval alchemical work) associated Salt with the ocean (salt-water), with the lunar symbolism of the unconscious, and with the feminine polarity (he saw Mercury as hermaphroditic).15 Symbolic specifics notwithstanding, salt as an alchemical symbol can best be understood as pertaining to the body-mind in a purified state, in which it serves as a proper vehicle for the full flowering of consciousness.

Alchemical Stages of Transformation

As mentioned, the key to alchemy is summarized in the Latin expression solve et coagula. ‘Solve’ here means to break down and separate elements and ‘coagula’ refers to their coming back together (coagulating) in a new, higher form. The alchemical idea of transmuting base metals into gold is also a metaphor for the inner Work. We must ‘break down’ aspects of our character that are in the way of the realization of our deeper, higher nature. This deeper, higher nature is the Philosopher’s Stone, and our ‘higher calling’ in life is represented by the symbol of gold. Thus, solve et coagula means to see clearly our limiting characteristics, take steps to wear them down by dispersal, and then to reconstitute in a higher, more pure form—which then allows for the possibility of accomplishing our maximum potentials in life.

There are, in some schools of thought, seven general stages in the alchemical process, which correspond to seven stages of individual transformation. Needless to say, as in all matters pertaining to alchemy, there is no overall consensus among alchemists or esoteric scholars as to the details of these stages. What follows is a simplified and psychologized overview of the seven stages, based on a scheme that is a good representation of the overall alchemical view of inner development.

1. Calcination: This is the first stage of

alchemy. Chemically, calcination is the term given for the heating and pulverizing

of raw matter to bring about its thermal decomposition, that is, its breaking

up (or down) into more than one substance, or into a phase shift (from, say,

water to gas at boiling point).

In spiritual symbolism, this stage is sometimes humorously referred to as ‘cooking’ or ‘baking’ (and in fact the prime symbol of this stage is fire). It occurs naturally in life as a process whereby our egos get gradually worn down by the inevitable challenges of life. In alchemical symbolism this stage is sometimes represented by bringing down a tyrannical king. The idea there is that we have two essential elements to us: our essence, and our ego-personality. The ego serves us in our early years, aiding in protection and survival, but becomes a problem as we seek to grow and mature into spiritually awake adults. The more we try to hold on to this limiting part of us, the more life will gradually hammer us—‘cooking’ us until we become sufficiently humbled to admit that we are going in a wrong direction. A hallmark of this stage is a growing willingness to be wrong about core issues, a willingness to let go of positions that we cling to. The expression from the book A Course In Miracles, ‘Would you rather be right or happy?’ speaks, in a simplified fashion, to this. The ego-self cares primarily about being right—right that we know, or right that we are not good enough, or right that we are too good, or right that we are a powerless victim, or right that we cannot trust life or love owing to previous experiences, and so on. Calcination is the process of beginning to get that part of our stubbornness, pride, and arrogance worn down. (This stubbornness, pride, or arrogance need not only express as an outwardly puffed up nature; indeed, more commonly it tends to disguise itself in shyness, self-doubt, or self-sabotage).

The sooner we understand the point that in most cases we are the architect of our own frustrations and failures, the better, because we can avoid years of unnecessary suffering. Ideally the spiritual path is about hastening the process of calcination, rather than it being drawn out over the course of a whole life, only to realize in old age just how intransigent and controlling we have always been. The reason why this process is so essential is because the personality we cling to, the sense of personal identity, the ‘me’ that we invest so much energy in maintaining, is ultimately illusory, based as it is on identification (with body, form, history, borrowed knowledge, and so on). Aging, and eventually death, will wear down and destroy this false self in time. Learning to let go of constructed mental positions, pride, excessive stubbornness, reactive blame of others, playing small owing to crippling self-doubt, and fear of confronting our falsehoods, will hasten the process and potentially give us more time to experience our deeper nature while still alive.

2. Dissolution: Chemically, ‘dissolution’, or ‘solvation’ as it is also called, refers to a process whereby a solute (like salt) dissolves in a solvent (like water).

Psycho-spiritually, the element that symbolizes dissolution is water, and this stage represents a deep encounter with our subconscious mind. After our ego has been sufficiently cooked (humbled) from calcination, what remains of our personality has to be further processed, and this is brought about by its dissolution in a solvent like water.

Dissolution, or deep deconstruction of the ego, is a challenging phase, especially for those with strongly developed personalities and egos. The common expression that someone ‘has a lot of personality’ is conventionally taken as a compliment, but from the point of view of psycho-spiritual alchemy it is problematic, because usually it just means that the person has a stronger ego-system and greater defences built up over time. Whether this ego is unpleasant or charming is secondary. Either way, it has to be dissolved in order for the true self to be liberated.

Ego-dissolution is directly related to our beginning to take responsibility for our projections—in short, to our beginning to truly grow up. We begin to move beyond victim-consciousness, the tendency to blame the world for our struggles, and the tendency to see in others what we most dislike about ourselves.

This stage is often characterized by experiencing the emotion of grief, and allowing ourselves to truly grieve painful incidents from our past that we may have long buried. Repressed or with-held pain keeps us dry and contracted. These psychic knots of pain need to be dissolved via permitting ourselves to truly experience the pain with awareness, as opposed to avoiding it with endless distractions, narcotizations (mind-altering substances like drugs or alcohol, including excessive T.V. watching), or endless other forms of avoidance. In many cases the stage of dissolution is forced on a person by unexpected accidents or illnesses. If a right attitude is brought to bear on such apparent misfortunes, overall maturing and growth can result.

A key to the stage of Dissolution is the awakening of passion, and the harnessing of the energy of emotional pain toward an object of creativity. We do not just passively witness the reality of our inner pain; we redirect its energy, wedding it to our authentic personal desires and constructive aims. In so doing we are participating and aiding in the dissolving of our false self. We are using the energy freed up by letting go of old, stale ego-positions, in the service of re-aligning our life in the direction of our higher purpose.

3. Separation: Chemically, separation, or ‘separation process’, refers to the appropriate extraction of one substance from another—for example, the extraction of gasoline from crude oil. In spiritual alchemy, separation refers to the need to make our thoughts and emotions more distinct by isolating them from other thoughts and emotions. For example, the process of forgiving someone is usually only authentic if we have first honestly recognized our negative thoughts and feelings toward that person, such as anger. We must first experience the anger prior to moving into an authentic forgiveness. When attempting to come to terms with our ‘shadow’-side, we need to identify and isolate particular elements of our character in order to honestly see and assess them. This is very much like a scientific process of extracting something from something else, in order to gain knowledge and insight about it. Developmentally it relates to the importance of a young adult differentiating from their parents (or other influential relatives) in order to clarify their own identify. On a socio-political level, it lies behind the idea of the separation of church and state.

This stage represents the need to focus on what has been revealed in us after the first two purification stages, so we can get clear on what precisely needs to be given attention. Navigated successfully, the separation stage aids us in taking a clearer stock of our life, honestly admitting our errors in judgment. A common symbol for this stage is the black crow, which in its color denotes the dying away of the false that has occurred in the first two stages, as well as the positive possibilities for the future symbolized by the crow’s capacity to fly.

The Separation stage is of crucial importance on the path of awakening, if only because it is most commonly both feared and overlooked. Many ‘feel-good’ approaches to personal transformation, or diluted new age teachings, in their rushed desire to reach an idealized state of unity with existence, gloss over the need to face and assume responsibility for one’s inner shadow element, or darker nature. The Separation stage is entirely concerned with the need to both see and take responsibility for the shadow within. If we fail to do this, the shadow elements will be projected onto the world, usually showing up in the form of others who appear to subject us to unjust treatment.

In this stage we begin to see what is of value in our life, and what is not. To illustrate the point with a simple example: back in the 1990s the former NY Times reporter Tony Schwartz quit his stressful job and decided to travel the country seeking out many prominent cutting edge psychologists, philosophers, and spiritual teachers and interviewing them. He wrote a book about his journey and what he’d learned from these teachers, titling it What Really Matters. When we’ve been humbled enough by life that we begin to recognize what really matters, then we’ve begun the alchemical process of separation. We are literally separating the wheat from the chaff both from within us and from our outer lives as well. However this is only possible when we are truly ready to be deeply honest with ourselves, by taking ownership of our frustrations and self-imposed limitations, and the entire range of thoughts and feelings within, from the positive to the negative—in short, of our entire self-image. Such a step makes it possible to achieve a radical breakthrough in our lives, something that may take the form of a thorough change in attitudes and inner positions, if not also in outer circumstances.

4. Conjunction: The fourth stage in the

alchemical process is conjunction. Psycho-spiritually, this refers to the

proper combining of the remaining elements of our being, after the purification

and clarification of the first three stages. It speaks to an inner unification

that is made possible by the hardships, purifications, and inner divisions that

happened in the first three stages.

The essence of psycho-spiritual conjunction is to provide an inner space in which to mediate between two apparently distinct opposites. For example, we all know what it is to experience conflicted feelings toward another person, especially someone we are close to, the typical ‘love-hate’ scenario. In the previous stage, separation, we need to distinguish these two states clearly if we are to be authentic. We need to be fully honest with ourselves about all of our inner states—put another way, we need to bring all of our unconscious thoughts and feelings about this person, and who/what they represent to us, to the light of consciousness. In conjunction, we worry less about totally unifying these thoughts and feelings than we do about developing the inner spaciousness in which to allow them to be there without condemning any as ‘wrong’. In this sense, ‘conjunction’ is not a forced joining of distinct and opposite states of mind, but rather a natural connecting process that happens as we honestly recognize the reality of both within us.

Additionally, esoteric alchemy proposes that what is left if the first three stages of calcination, dissolution, and separation have been properly undergone is a state wherein we can more clearly mediate between our ‘soul’ and ‘spirit’. In this sense ‘soul’ refers to our embodied spirit, the part of our essential nature that is fully on Earth, and ‘spirit’ refers to our most rarefied connection with the divine, transcendental Source. These two are sometimes categorized as the divine feminine (soul) and the divine masculine (spirit). The combining of the two is the essence of inner tantra, a sacred marriage of spiritual opposites, or what the depth psychologist C.G. Jung called the mysterium coniunctionis. Alchemical symbolism sometimes refers to this as the marriage of the Sun (spirit) and the Moon (soul).

All this speaks to the important of balance on our path of awakening, and in particular, direct and honest awareness of those parts of us that remain out of balance. In achieving a conscious balance of our spirit-soul/masculine-feminine energies, we become capable of deeper spiritual realizations and more effective manifestations in our life. Put in practical terms, we maintain a balance between our maximum context transcendent awareness (meditation) and our embodied, integrated immanence (which is essentially relationship, in all its forms—relationship with others, with our practical affairs, our immediate surroundings, and so on).

The conjunction phase is sometimes compared to the spiritual Heart (or ‘heart chakra’), which as metaphor speaks to the ability to ‘hold a space’ in which conflicting elements can work out their differences and become resolved to a higher potential. It is here where we realize a definite maturity, understanding that differences, especially those of polar opposite qualities, do not get resolved via force, but rather by holding space, i.e., cultivating the patience to allow integration and change to occur organically.

However this stage is not the end of our process of transformation, as elements of ego remain, and must in turn be processed.

5. Fermentation: In biochemistry, ‘fermentation’ refers to the process of oxidizing organic compounds (changing their oxidation state). Examples of products of fermentation are beers and wines. In spiritual alchemy, fermentation has to do with a new stage in the process of transformation in which so-called higher energies begin to be tapped in to. The first four stages all dealt with the energies of the personality (and its remnants), but with fermentation we are beginning to access the energies of the higher dimensions (or subtle inner planes, depending on how we view it).

Fermentation occurs in two parts, the first being Putrefaction. In biology, putrefaction refers to the breakdown or decomposition of organic material by certain bacteria. Spiritually, this refers to a kind of inner death process in which old, discarded elements of the personality are allowed to rot and decompose. It is sometimes referred to as the dark night of the soul, and can involve difficult mental states such as depression. In the Tarot, this phase is represented by the Death card, which denotes the death of an aspect of our lower self that no longer is needed.

Putrefaction is followed by a stage called Spiritization. Here, we undergo a type of rebirth resulting from the deep willingness to let-go of all elements of us that no longer serve our spiritual evolution. This marks the true beginning of inner initiation, of entry into a ‘higher’ life in which our best destiny has a chance to unfold.

6. Distillation: Chemically, distillation refers to a separation process of substances. It has a long history, being used for the production of such things as alcohol and gasoline. Psychologically, distillation represents a further purification process, being about an ongoing process of integrating our spiritual realizations with our daily lives—dealing with seeming mundane things with integrity, being as impeccable in our lives as we can be, and not using the inner work as a means by which to escape the world. At this stage remaining impurities, hidden as ‘shadow’ elements in the mind, are flushed out and released, crucial if they are not to surface later on (a phenomena that can be seen to occur when a reputed saint, sage, or wise person, operating from a relatively advanced level of self-realization, appears to have a fall from grace). Repeatedly practicing this leads to a strong and profound inner transformation that is rooted in integrity. Most standard definitions of ‘enlightenment’, in the Eastern sense of that word, correspond to this stage. A common alchemical symbol for this stage is the Green Lion eating the sun. It suggests a robust triumph and an embracing of a limitless source of energy.

7. Coagulation: This stage brings to a completion the seven phases of the Solve et Coagula process of alchemy. Biologically, ‘coagulate’ refers to the blood’s ability to form clots and so stem bleeding, thus being a crucial life-saving function. In spiritual alchemy it symbolizes the final balancing of opposites, symbolized in the Tarot by the meeting of Magician and Devil, or higher self and the raw material of form, the ultimate marriage of Heaven and Hell. The end result is the Philosopher’s Stone, also sometimes called the Androgyne, and is often symbolized by the Phoenix, the bird that has arisen from the ashes. This is closely connected to the idea of the Resurrection Body of mystical Christianity, or the Rainbow Body of Tibetan Buddhism, which includes the esoteric idea of the ability to navigate all possible levels (dimensions) of reality, without loss of consciousness. It is the form of the illumined and fully transformed human, in which matter has been spiritualized, or the spiritual has fully entered the material. Heaven and Earth as seen as one, or as the Buddhists say, nirvana (the absolute, or formless) is samsara (the world of form). At this end stage, whatever we set eyes on we see the divine, as we have come to realize our own full divinity. We have arisen from the ashes of limited individuality, and been reborn as our true Self.

Three Stages of Transformation

The above describes seven stages of transformation. Spiritual alchemy in places abbreviates all this into a more compact scheme. From roughly the time of Christ until up to the 15th or 16th centuries, it was defined as four essential stages, based on four colors mentioned by Heraclitus, via the following Greek-Latin terms: melanosis or nigredo (blackening), leukosis or albedo (whitening), xanthosis or flavum (yellowing), and iosis or rubedo (reddening). By the 1500s the stage of ‘yellowing’ was gradually dropped, on rare occasions replaced by ‘greening’.

Nigredo: Nigredo means ‘blackening’. Traditionally it referred to the challenging and often discouraging first phase of the alchemist’s work, in which they would be compelled to face directly into the chaotic void—what the Old Testament referred to as the ‘face of the deep’. Nigredo represents the first stage of awakening, characterized by a breaking down, or a challenging encounter with the parts of our ego that are clearly in the way of our inner growth. The process of nigredo begins as we truly and sincerely begin to walk the path of transformation. The first step faced by all who desire to know themselves is to face the ego, and in particular, its means of sabotaging our inner flowering and overall success in life. In the seven-stage scheme presented above, nigredo may be said to encompass the first two stages, calcination and dissolution.

Albedo: Albedo means ‘whitening’. In this phase, the alchemist brought to completion the work of nigredo—the confrontation with the chaotic, undifferentiated void—by separating things and creating division, i.e., two substances in opposition to each other. This phase of the Great Work thus involves the creation of division necessary for the further unification of these opposites (for e.g., Spirit and body). It is here that the symbol of Mercury plays a crucial role, representing the guidance and assistance that appears to come from outside of the personality and ego-system, and that brings about the corrective balancing and integrating of the opposites, a process referred to by the term mysterium coniunctionis. Albedo also refers to the inner light that arises in the face of genuine suffering and the breaking down of old conditioning brought about by the first stage. The white dove is a common symbol for this stage. Albedo corresponds to the above stages of separation, conjunction, fermentation, and distillation. It is in this stage where a kind of rebirth happens for us, once we have dispensed sufficiently with the old conditioning of the ego, via the stages of encountering the void, creating coherence and clarity via division into opposites, and re-unifying these opposites.

Rubedo: Rubedo, meaning ‘reddening’, is the final stage. Whereas nigredo and albedo were concerned with the chaotic void and division, rubedo is entirely concerned with unity, with the result of this unity being the Philosopher’s Stone. The figure of Mercury herein undergoes a symbolic change, no longer being seen as the cause of the process of synthesis of opposites, but now as the goal itself, leading us back to the state of integrated wholeness and unity. However, this wholeness is not a mere return to the Primal state (something Freud, for one, defined as ‘infantile regression’). Rather, we re-capture the primal unity of the child-like state, while at the same time achieving something much more, the mature wisdom of a sage.16 Rubedo thus points toward genuine self-realization occurring while still in a physical body. It corresponds more or less to the last stage in the seven stage scheme, that of coagulation. This stage is the main objective behind all inner practices of spiritual transformation (although it may be confidently said that very few truly reach this stage in their lifetime). Nevertheless it remains the goal, the light at the end of the long, dark tunnel of embodied existence that we all seek, even if not always consciously.

Notes

1. James Hannam, God’s Philosophers: How the Medieval World Laid the Foundations of Modern Science (Australia: Allen & Unwin, 2010), p. 131.

2. P.G. Maxwell-Stuart, The Chemical Choir: A History of Alchemy (London: Continuum Books, 2008), p. 1; p. 19.

3. One of the most thorough and concise histories of Western alchemy is Mircea Eliade’s The Forge and the Crucible, originally published in French in 1956, first English translation by Rider and Company in 1962.

4. For those interested in practical laboratory alchemy, a good primer to begin with is Brian Cotnoir, The Weiser Concise Guide to Alchemy (Weiser Books, 2006).

5. Rudolf Bernoulli, Spiritual Development as Reflected in Alchemy and Related Disciplines; from Spiritual Disciplines: Papers from the Eranos Yearbooks, edited by Joseph Campbell (New York: Bollingen Foundation, 1985), pp. 308-309.

6. Julius Evola, The Hermetic Tradition: Symbols and Teachings of the Royal Art (Rochester: Inner Traditions International, 1995), p. xi.

7. Catherine MacCoun, On Becoming an Alchemist: A Guide for the Modern Magician (Boston: Trumpeter Books, 2008), p. 164.

8. Mircea Eliade, The Forge and The Crucible: The Origins and Structures of Alchemy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978), p. 153.

9. Charles Ponce, The Game of Wizards: Psyche, Science, and Symbol in the Occult (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1975), pp. 181-182.

10. Empedocles, in his Fragments, refers to the elements as sun, earth, sky, and sea.

11. Empedocles of Acragas: Fragments, www.abu.nb.ca/courses/grphil/EmpedoclesText.htm, accessed April 4, 2012.

12. Eliade, The Forge and The Crucible, p. 79.

13. Titus Burckhardt, Alchemy: Science of the Cosmos, Science of the Soul (Louisville, Kentucky: Fons Vitae, 2006; originally published by Walter Verlag-Ag, 1960), p. 95.

14. Ibid., p. 140.

15. Mark Haeffner, The Dictionary of Alchemy: From Maria Prophetissa to Isaac Newton

(London: The Aquarian Press, 1991), p. 225.

16. Karen-Clair Voss, Spiritual Alchemy; from Gnosis and Hermeticism: From Antiquity to Modern Times, edited by Roelof van den Broek and Wouter J. Hanegraaff (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1998), pp. 160-161.

Copyright 2008-2012 by P.T. Mistlberger, all rights reserved.