Jesus and Judas

Brothers in Spirit

by P.T. Mistlberger

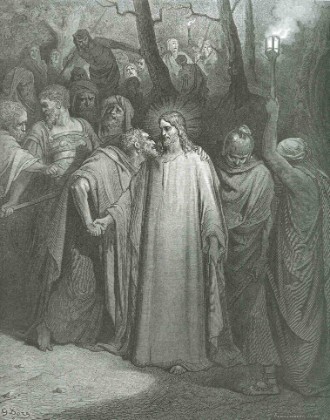

And forthwith he came to Jesus, and said, Hail, master; and kissed him. (Matthew, 26:49, KJV).

The relationship between Jesus and Judas has long been regarded as the quintessential relationship of conflict, involving in particular the theme of betrayal. In the annals of Western literature, perhaps no figure has been as universally reviled as Judas (with Dante notoriously depicting him inhabiting the lowest realm of Hell in a state of perpetual agony). Throughout the centuries the Judas-stereotype has come to be associated with a treachery based on selfish agendas, and far worse, with the stereotype of the greedy and untrustworthy Jew, the ‘Christ-killer’. This stereotype is, however, loaded with internal contradictions—most obvious being that the death of Jesus made possible his crucifixion and (according to Christian doctrine) his resurrection, without which there would be no basis to the orthodox Christian faith. Accordingly, Judas played a key role in the fulfillment of Jesus’ destiny as Messiah. That aside, the relationship between these two figures, though of many possible dimensions (depending on interpretation), is a rich basis for a study in conflict, despite the fact that traditional dogma presents Jesus as of infinite significance, and Judas as a mere common traitor.

As with all the grand historical conflicted relationships, there are two essential elements to consider: first, the outer historical perspective, with particular emphasis on 20th century advances in critical study of the Bible, including the recent discovery of the highly controversial Gnostic Gospel of Judas (see below), and second, the inner psycho-spiritual theme of the relationship, and its applicability to patterns that surface in our own lives.

The Historical Jesus

The idea of a ‘historical Jesus’ needs to be understood as that which differs from a ‘doctrinal Jesus’ or a ‘mystical Jesus’. The doctrinal Jesus—also known by scholars as the ‘dogmatic Christ’—is a figure who conforms to views and conclusions as established by various authoritative councils down through the centuries. The classic example of this is the Jesus who conforms to some of the conclusions of the renowned Council of Nicaea (located in present-day northwestern Turkey) of 325 C.E. It was during this council that the presiding bishops officially set as dogma the Nicene Creed, at the same time declaring the opposing theology (‘Arianism’) a heresy. The Nicene Creed declared that Jesus was ‘of one substance with the Father’—defined by the word homousios—implying that Christ was both fully human and fully God. Arianism was the name given retroactively to the ideas put forth by Bishop Arius (251?-336), who had argued that God the Father was necessarily of singular primacy, and forever superior to the Son (Christ), whom he had created. With the success of the Nicene Creed, the views of Arius—and all other views of Christ that did not acknowledge him as God incarnate—became heretical to orthodox Christianity.1

The ‘mystical Christ’ is something far more nebulous and complex than the dogmatic Christ, because the mystical Christ is, in some respects, the Christ as understood by anyone who has a direct, transpersonal experience that he or she believes reveals something about the nature of Christ. Obviously, there is nothing objective here. The mystical Christ is, in some ways, polar opposite to the historical Jesus, although it is certainly possible to integrate the two to one’s personal satisfaction.

Outside of the dogmatic Christ and the mystical Christ, is the historical Jesus. This is the figure that emerges from a close, rational analysis of the various scriptures, both canonical and apocryphal, as well as from a consideration of secular sources written around the time he lived. The idea of applying historical method to the study of scriptures, and ultimately to that of the figure of Jesus himself, is a relatively recent phenomenon. It had its roots, indirectly, in the rise of modern science during the 17th century ‘Age of Reason’, in particular via the work of Copernicus and Galileo, both of whom combined to alter the world-view within Christendom at that time. The essence of this paradigm shift was that man was no longer the center of the universe, reflecting the new heliocentric (Sun-centered) view of the solar system deduced by Copernicus, and visually confirmed by Galileo. What science had single handedly demonstrated was that the force of reason (via Copernicus’ logic) and empirical observation (via Galileo’s primitive telescope) was enough to overturn an old dogmatic worldview, and completely reorient our understanding of the universe and Man’s role—and most importantly, his relative significance—in it.

It was from this emerging climate of slowly developing intellectual rigor that the first historical studies of Jesus began to appear, mostly via the German scholars Hermann Reimarus (1694-1768) and David Friedrich Strauss (1808-1874). It was from these two that the essential pillars of modern biblical criticism developed, these pillars consisting of differentiating the historical Jesus from the Christ of dogma as defined by the early creeds, and of recognizing the large differences between the three ‘synoptic Gospels’ (Mark, Matthew, and Luke), and the fourth Gospel (John).2 Critical scholarship applied to the life of Jesus began to develop further with the work of the important German scholar Rudolf Bultmann (1884-1976), and then began to hit its stride in the mid 1980s with the founding of the ‘Jesus Seminar’ by Bible scholars Robert Funk, John Dominic Crossan, Marcus Borg, and others, under sponsorship of the Westar Institute. This group, aided by up to two hundred (mostly liberal) scholars, eventually produced a work that gave a cautious estimation of what exactly Jesus probably did and did not say, based on the words traditionally ascribed to him. The Jesus Seminar concluded that 82% of the words that he is supposed to have said, according to the four traditional Gospels, were ‘not actually spoken by him’.3 (This, predictably, unleashed a firestorm of controversy from conservative Christians, who then attempted to attack the findings of the Jesus Seminar from many angles; one result from the backlash was that some Seminar Fellows had to resign their teaching posts).

Many things emerged from this critical analysis of the Gospels and other associated writings. Above all, the conventional image of Jesus came to be seen as one carefully crafted over many centuries by ‘authorities’ with agendas, perhaps the greatest of these being the decision to create a faith rooted in a claim of spiritual supremacy. The Nicene Creed does not proclaim Jesus as just one incarnation of God (as Hindus do with Krishna), or as just one in a long line of Awakened Ones (as Buddhism does with Gautama Buddha), or as the last and greatest of the Prophets (as Islam does with Mohammad). It rather asserts that Jesus, and only Jesus, was God, and that the words ascribed to him from John’s Gospel, ‘I am the way, the truth, and the life, no man cometh unto the Father, but by me’ (John 14:6, KJV), carry supreme (and ultimately severe) import.

Critical scholarship has in general come to a number of conclusions, and many of these were published in the early 1990s, a heyday for a wider public outreach by scholars of the historical Jesus. Amongst these have been: no evidence that Herod ‘murdered babies’ en masse in the infamous ‘slaughter of the innocents’ in an attempt to eliminate Jesus as a possible rival king; that Jesus was likely born in Nazareth, not Bethlehem; that he never claimed to be the Messiah, or the ‘Son of God’; that he was not born of a ‘virgin birth’; and that the resurrection story, as literally told, is almost certainly a fairy tale.4

There have even been credible arguments advanced that Jesus never in fact existed. These views have been lent weight by the almost total lack of corroborating evidence for the existence of Jesus by contemporary historians of his time. Only one, the famous Jewish historian Flavius Josephus (37-100 C.E.) appeared to make mention of Jesus, but the short passage where he described him has been judged as so ludicrously over the top as to be almost certainly a clumsy insertion by some later Christian scribe. However, further closer analysis has come to view this passage as having likely been exaggerated, rather than fabricated altogether.5 That, along with a general consensus that the surviving letters of Paul, four Gospels, and later Gnostic gospels, in all likelihood describe a person who in some fashion existed, have relegated the ‘Jesus never existed’ position as out of favor amongst even the most skeptical historians.

Nevertheless, the views that emerge of the historical Jesus are enough to seriously alter the faith, to the point where it is barely recognizable as the traditional Christianity that has held sway for the past 1,700 years. This is because Christianity is, above all, a historical faith, resting crucially on the assumed factuality of certain historical events, foremost in importance of which is the resurrection. Without Jesus’ victory over death, his ascension, he is just another Jewish sage, and certainly not the ‘sole Son of God’.

Limitations of space make it impossible here to cover the full arguments behind the critical scholarship of the historical Jesus. What follows is a brief summary of some of the conclusions of the critical deconstruction done by historians and scholars of the more traditional and important Christian beliefs concerning the events of the life of Jesus. (The interested reader can pursue more comprehensive analysis of these matters in the various writings mentioned in the Notes section to this chapter).

Virgin Birth

New Testament scholarship has managed, over the years, to reach a strong general consensus about some matters concerning the four traditional (canonical) Gospels. Three—those of Mark, Matthew, and Luke—are called the ‘synoptic’ Gospels, because they share a close similarity in narrative content (‘synoptic’ is Greek for ‘seen together’). The fourth, John’s Gospel, has a much different tone and is believed to have been written a couple of decades later. (Significantly, the scholars of the Jesus Seminar concluded that practically nothing in John’s Gospel ascribed to Jesus was actually said by him).

Scholars are now more or less unanimous that the oldest is Mark’s Gospel, which is believed to have been written down around 70 C.E. (that is, roughly forty years after Jesus’ death). The reason Mark’s Gospel is viewed as the oldest is primarily due to the fact that Matthew and Luke’s Gospels, while differing on some points, share common passages that are all found in Mark. Matthew’s Gospel is believed to have been written around 80 C.E., with Luke’s following shortly after. John’s Gospel is believed to have been scribed around 100 C.E. It is now largely agreed that none of the actual authors of the Gospels went by the names attributed to the Gospels, and thus were likely anonymous scribes.

Problems around the traditional stories of the birth of Jesus begin with the conflicting versions found in Matthew and Luke (Mark and John have nothing to say about Jesus’ birth). The fantastic story of the ‘magi’ from the East, and the strange, mobile ‘star’ that appears and disappears and eventually points out where the infant Jesus is lying in a manger in Bethlehem—a story told in only one of the four Gospels (Matthew)—has long been recognized as myth by serious scholars. The same is believed to be the case with Luke’s tale of a ‘decree from Caesar Augustus’ shortly before the birth of Jesus in Bethlehem.6 Not only are these stories full of internal contradictions, they were, in the case of both Matthew’s Nativity story and Luke’s account of Jesus’ birth, written down approximately fifty years after Jesus died. One has only to imagine how a story told at this time of writing (2010), concerning an event that occurred half a century ago (in 1960), would be subject to distortion—especially given that there was no recording technology in the 1st century and writing amongst the general population was rare enough. Fifty years—essentially, two generations—is a long enough time to cause a story told at its beginning to resemble nothing of the truth that actually happened, once told at the end.

Problems around the traditional stories of the birth of Jesus begin with the conflicting versions found in Matthew and Luke (Mark and John have nothing to say about Jesus’ birth). The fantastic story of the ‘magi’ from the East, and the strange, mobile ‘star’ that appears and disappears and eventually points out where the infant Jesus is lying in a manger in Bethlehem—a story told in only one of the four Gospels (Matthew)—has long been recognized as myth by serious scholars. The same is believed to be the case with Luke’s tale of a ‘decree from Caesar Augustus’ shortly before the birth of Jesus in Bethlehem.6 Not only are these stories full of internal contradictions, they were, in the case of both Matthew’s Nativity story and Luke’s account of Jesus’ birth, written down approximately fifty years after Jesus died. One has only to imagine how a story told at this time of writing (2010), concerning an event that occurred half a century ago (in 1960), would be subject to distortion—especially given that there was no recording technology in the 1st century and writing amongst the general population was rare enough. Fifty years—essentially, two generations—is a long enough time to cause a story told at its beginning to resemble nothing of the truth that actually happened, once told at the end.

However, in the case of Matthew and Luke, the evidence does not point so much toward problems with memory or the capacity to record past events accurately. The evidence rather points toward a deliberate fabrication of a myth, in order to allow for the fulfillment of certain key prophecies from the Old Testament—prophecies that the authors of Matthew and Luke saw as essential to fulfill for the new Jewish Messiah. They could do this because for them, something much bigger was at stake, a conviction likely based in part on genuine mystical certitude, and in part on a desire to revolutionize the religio-political landscape of the time. The Kingdom of God was afoot, his Messiah had recently walked the earth, and therefore, some sort of fulfillment of prophecy was necessary in order to consolidate the idea that Jesus was the culmination of all that had come before. As John Dominic Crossan pointed out, the important question is not so much the details of Jesus’ birth provided by Luke and Matthew, but the more central issue is why these two Gospel authors are bothering to provide such details in the first place. As Crossan wrote,

Greatness later on, when everybody was paying attention, is retrojected onto earlier origins, when nobody was interested. A marvelous life and death demands and gets, in retrospect, a marvelous conception and birth.7

In other words, a myth is constructed to reinforce the legitimacy of a powerful spiritual teacher, for a greater purpose—one that Matthew and Luke saw as infinitely more important than mere historical veracity.

The number of internal contradiction in the Gospels concerning the history of Jesus, his genealogy, the manner and place of his birth, and so forth, are so many that it soon becomes clear to the unbiased reader that the New Testament is not a true historical document, but rather a document of faith. Even most Christian faithful would not ultimately deny that, despite the fact that the Bible does contain actual history. As the German historian and Bible scholar Rudolf Bultmann pointed out, ‘only the crucifixion matters’; that is, for an actual inner or mystical connection with Christ, or faith in what he represents, the more outlandish New Testament legends and myths are not necessary.

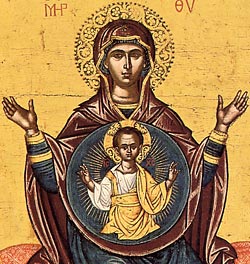

An interesting example of the psychology of faith is found especially in the beliefs developed over the centuries, by Catholics in particular, around Mary, the mother of Jesus. Although she is actually only a minor player in the Bible, with few mentions, her cult grew over the centuries to the point where ‘Marian visions’ are commonly claimed by many even in current times. She particularly came into vogue during the dark times of the Middle Ages, especially during plague outbreaks, where Jesus was seen more as a figure of judgment and righteousness, and Mary regarded more as a source of compassion and mercy. The idea of Mary being a virgin—claimed only by Matthew and Luke, but not by Mark, John, or Paul (the latter of whom wrote that Jesus was ‘born of a woman’)—partly has its basis in a problematic translation of a Hebrew word found in one of Isaiah’s prophecies of the Old Testament:

An interesting example of the psychology of faith is found especially in the beliefs developed over the centuries, by Catholics in particular, around Mary, the mother of Jesus. Although she is actually only a minor player in the Bible, with few mentions, her cult grew over the centuries to the point where ‘Marian visions’ are commonly claimed by many even in current times. She particularly came into vogue during the dark times of the Middle Ages, especially during plague outbreaks, where Jesus was seen more as a figure of judgment and righteousness, and Mary regarded more as a source of compassion and mercy. The idea of Mary being a virgin—claimed only by Matthew and Luke, but not by Mark, John, or Paul (the latter of whom wrote that Jesus was ‘born of a woman’)—partly has its basis in a problematic translation of a Hebrew word found in one of Isaiah’s prophecies of the Old Testament:

Therefore the Lord Himself will give you a sign: Behold, a virgin will be with child and bear a son, and she will call His name Immanuel. (Isaiah 7:14, KJV).

The original Hebrew word translated as ‘virgin’ was almah, a word that in addition to meaning ‘virgin’, also means ‘maiden’ or ‘young woman’—and it is in these latter meanings of the word that almah is used in other parts of the Bible (for example, in Exodus 2:8, Proverbs 30:19, and other places). The problem arose when the Hebrew version was translated into Greek, at which point almah became parthenos, a Greek word which does indeed mean ‘virgin’. But the original Hebrew word was ambiguous, and was usually employed in the Bible to mean simply a young woman. The Hebrew word used to specifically denote a virgin is betulah, and this is the word actually used in the Bible on several occasion to imply just that (for example, Genesis 24:16, or Deuteronomy 22:13-21).8

I cite this example to illustrate a key point, one that we will consider more fully below, in looking at the archetypal significance of the relationship between Jesus and Judas. The point boils down to, what really matters. The problem with conflict, whether of the large scale sort, or within the micro personal realm, is in the loss of context. Loss of context occurs when matters are improperly prioritized, when perspective is utterly lost. Wars between, or within, religions have found much of their causes sourced in doctrinal differences, which are then used as excuses to justify aggression, or related reasons for conflict. But too often these doctrinal differences are largely a matter of getting caught up in historical trivialities, legends, or outright myths.

There is arguably an equivalent psychological problem associated with the idea of a ‘virgin birth’ and ‘virgin Mother of God’, and it touches on a core issue found in religion in general, that being the relationship between the spiritual and the carnal, between the ‘higher’ and the ‘lower’. To associate the ‘Mother of God’ with virginity is, by extension, to associate the sexual with that which is ‘not divine’. It is to introduce, albeit through the back door, the notion that there is something ‘sinful’, or at the least, not spiritual, in the act of sexual intercourse. Jesus, as God Himself, is so pure that he cannot enter into the world in a natural fashion. The implication is that he himself was a virgin. The message is relatively clear: sex is not divine, or at the least, is beneath the Son of God, and his mother as well.

Son of God

Problems involving the status of Jesus as Messiah and sole Son of God, something emphasized in the Bible and in an extreme way by the early Church Fathers, begin in Luke with his genealogy that attempts to prove that Jesus is a direct descendant of Adam. As numerous critics have pointed out, there is an absurdity in this, and it is simple: if Adam was the Primordial Man, then we are all descended from him. So what was the point of proving that Jesus was? Luke’s attempt here is roughly equivalent to Matthew claiming that a star in the sky was pointing at one particular manger in Bethlehem—when in fact a star in the sky could be demonstrated to be pointing at anything on earth, depending on the perspective one takes in looking at it. (Many interpretations have been suggested for the ‘star of the Magi’, everything from a planetary conjunction to a supernova, and even a UFO, but needless to say, no idea has emerged as the best candidate, beyond this rather restless star being a literary device to aid in Matthew’s desire to have Jesus born in Bethlehem so as to conform to Old Testament prophecies). As the historian G. A. Wells put it, ‘Matthew represents the nativity as fulfillment of prophecy by means of fantastically arbitrary interpretation of numerous Old Testament passages.’9

The deeper problem with Matthew’s and Luke’s accounts of Jesus’ genealogy is that they do not cooperate with the claim of the virgin birth. Both have Jesus descending via Adam or David to Joseph (his father). But this makes no sense if he was conceived miraculously via the agent of the Holy Spirit (as traditionally recounted). Either his was a virgin birth, or he was conceived via the aid of sperm from Joseph. If he was a virgin birth, then the whole genealogy chart tracing him back to Adam is nullified. If he was conceived by natural means, then the virgin birth—and the whole cult of Mary as the virgin Mother of God—is erased. As Ute Ranke-Heinemann vividly put it, ‘It’s a kind of theological schizophrenia when the good Catholic can, indeed should, say ‘Jesus is the son of David’, but may never say ‘Jesus is the son of Joseph’—when Jesus is the son of David only through Joseph.’10 Also, the respective genealogies of Jesus offered by Matthew and Luke do not agree with each other.

As the Catholic theologian Hans Kung once wrote about the attempts in the Gospels to define the personal history of Jesus, ‘Today even Catholic exegetes concede that these stories are historically largely uncertain, mutually contradictory, strongly legendary, and in the last analysis theologically motivated’.11 (In part for observations such as these, Kung was forbidden by the Vatican to teach Catholic theology, although he remains a priest ‘in good standing’).

The simple truth is that the historical Jesus of Nazareth is really not reconcilable with the Jesus of faith—the Incarnation (and Son) of God. In a span of around three hundred years, Jesus of Nazareth became the Christ of the Nicene Creed as ratified by Emperor Constantine and a few hundred bishops in Nicaea in 325 C.E. He went from being a wandering Jewish sage—perhaps similar in some respects to a youthful version of Siddhartha Gautama (the historical Buddha)—to God Himself, the Logos, the Infinite One, both the Son of the Father and the Father Himself, forever distinct from mere humanity and human beings.

Resurrection

Beyond all the miracles ascribed to Jesus in the New Testament—and there were many, everything from elemental magic (converting substances, such as water into wine, multiplying food supplies, and controlling weather), to more yogic feats such as walking on water, to the feats of an exorcist (casting out demons), to healing the sick—his most spectacular involved his mastery over death. He is reputed to have brought back to life several people who had recently died. The most famous of those stories involved Lazarus, whom it was reported that Jesus revived four days after he had died.

In the Gospels Jesus is depicted as a powerful miracle-worker, but he was not actually unique in these abilities. During his own time and place mystics and healers—what would perhaps be known today by the more common term of ‘shaman’—were legion. The rest of the world has been no stranger to these wonder-workers and their reputed abilities either. The Orient, in particular India and the Tibetan highlands, has abounded for centuries with mystics and magicians of all stripes, claiming all sorts of spectacular powers (some of which were witnessed by objective observers, and still commonly are). Even being credited with the act of reviving dead people is not a claim unique to Jesus—the famous Indian tantric master Padmasambhava, one of the founders of Tibetan Buddhism, was reputed to have had this power, and even to have taught it to at least one of his disciples.12

However the miracle that set Jesus apart, at least according to his followers, was his own personal conquest of death, in the form of his bodily resurrection three days after his crucifixion. The story of this event is crucial to orthodox Christianity.13 The different Gospels report different details; for example, Matthew has an earthquake occurring after Jesus dies on the cross, followed by tombs bursting open and ‘God’s saints’ suddenly resurrecting. Jesus’ body is eventually taken down, and sealed in a tomb with a heavy round stone. This was reported to have occurred on the Friday (‘Good Friday’). On Sunday (now celebrated as ‘Easter Sunday’), two disciples (Mary Magdalene and the ‘other Mary’) go to the tomb to anoint Jesus’ body, only to discover that the tomb has been opened and the body is gone. The Gospels differ slightly on details, but the essential legend is set in place: Jesus has resurrected, that is, his physical body had mysteriously and miraculously transformed into some sort of ethereal ‘light body’. In some Gospel versions, Mary Magdalene sees this body of light, and converses with it. Jesus tells her to tell the disciples to go to Galilee, where he will appear to them. This he does, in a series of events in which the disciples are depicted as being both skeptical (as in the legendary ‘doubting Thomas’ parable) and somewhat dim-witted. Eventually they accept that it is really Jesus, and he ascends fully to heaven.

However the miracle that set Jesus apart, at least according to his followers, was his own personal conquest of death, in the form of his bodily resurrection three days after his crucifixion. The story of this event is crucial to orthodox Christianity.13 The different Gospels report different details; for example, Matthew has an earthquake occurring after Jesus dies on the cross, followed by tombs bursting open and ‘God’s saints’ suddenly resurrecting. Jesus’ body is eventually taken down, and sealed in a tomb with a heavy round stone. This was reported to have occurred on the Friday (‘Good Friday’). On Sunday (now celebrated as ‘Easter Sunday’), two disciples (Mary Magdalene and the ‘other Mary’) go to the tomb to anoint Jesus’ body, only to discover that the tomb has been opened and the body is gone. The Gospels differ slightly on details, but the essential legend is set in place: Jesus has resurrected, that is, his physical body had mysteriously and miraculously transformed into some sort of ethereal ‘light body’. In some Gospel versions, Mary Magdalene sees this body of light, and converses with it. Jesus tells her to tell the disciples to go to Galilee, where he will appear to them. This he does, in a series of events in which the disciples are depicted as being both skeptical (as in the legendary ‘doubting Thomas’ parable) and somewhat dim-witted. Eventually they accept that it is really Jesus, and he ascends fully to heaven.

The fact that the Gospels differ somewhat in details around the death of Jesus is considered, by most Christian theologians, much less important than the essential mystery and teaching that is being transmitted via the story. That is, the legend is more powerful than any ‘accurate history’, because all that really matters is the interpretation of the event, and the inner meaning it carries for any who place their trust and faith in Christ as supreme Messiah.

There is merit to this viewpoint; historical nit-picking does at times seem silly and sort of meaningless when standing in contrast to the deeper meaning intended behind the story, whether that meaning be seen as the reality and supremacy of the personal Christ (as in the orthodox view) or as the reality and supremacy of impersonal Spirit over matter (as in the more mystical Gnostic view). The problem, however, arises when biases are reinforced by legendary stories or mythic events, such as, for example, the racial bias against Jews that was perpetrated by the Church for centuries, all centered on the traitor Judas and the ‘Christ-killing’ Jews. The Gospels framed the Jews as the killers of Christ, even though crucifixion was a Roman practice (never a Jewish one) and it was a Roman Prefect (Pilate) who authorized the crucifixion of Jesus. (It was not until 1959 that Pope John XXIII struck an anti-Semitic phrase (‘perfidious Jews’) from Catholic prayer; and it was not until 1962 that the Catholic church officially exonerated Jews as ‘God-killers’).

The Historical Judas

We are now ready to look at the other main player of this chapter. Judas factors into all of this because as the alleged ‘betrayer’ of Jesus he is the one who sets in motion the events that make possible Jesus’ arrest, trial, crucifixion, and resurrection. What actually is Judas’ full role in the Gospels, and what is known of the historical Judas?

In fact, Judas has only a small (if crucial) role in the Gospels, with just over a thousand words dedicated to discussing this shadowy figure. His most notorious moment comes, as is well known, when he betrays Jesus to Roman guards (or in some versions, a mob). This takes place immediately after the Last Supper, a special feast in which Jesus and all twelve disciples were present. However, the four Gospels do not report the events of the Last Supper in the same way; Mark, Matthew, and Luke never mention Judas leaving the Last Supper, which he would have had to do to fetch the guards who arrested Jesus. In John’s Gospel this apparent oversight is corrected, and a scene is described in which Jesus hands a piece of bread to Judas. According to John, it was at this moment that ‘Satan’ entered Judas, and Jesus then says to him ‘What you are going to do, do quickly’. Judas then leaves. (Luke has Satan entering Judas before the Last Supper; Mark and Matthew make no mention of Satan entering Judas).

It’s in the scene immediately following that Jesus and the disciples retire to Gethsemane to a grove of sorts, and as Jesus prays, to his disappointment, the disciples fall asleep. Jesus rebukes them for this but then basically says, ‘never mind, my time is up, my betrayer has arrived’, at which point Judas shows up with the soldiers/mob. He then betrays his master with the infamous kiss. One of the disciples (in some versions, Simon Peter) attempts to use force to protect his master from the guards, but Jesus stops him, uttering the famous line, ‘for all they that take the sword shall perish with the sword’ (Matthew 26: 52, KJV). According to Mark, Jesus was captured at night because the Jewish priests wished to avoid possible riots caused by crowds protesting the arrest. Jesus is then led off, where he is tried, convicted, and crucified in relatively short order.

It’s in the scene immediately following that Jesus and the disciples retire to Gethsemane to a grove of sorts, and as Jesus prays, to his disappointment, the disciples fall asleep. Jesus rebukes them for this but then basically says, ‘never mind, my time is up, my betrayer has arrived’, at which point Judas shows up with the soldiers/mob. He then betrays his master with the infamous kiss. One of the disciples (in some versions, Simon Peter) attempts to use force to protect his master from the guards, but Jesus stops him, uttering the famous line, ‘for all they that take the sword shall perish with the sword’ (Matthew 26: 52, KJV). According to Mark, Jesus was captured at night because the Jewish priests wished to avoid possible riots caused by crowds protesting the arrest. Jesus is then led off, where he is tried, convicted, and crucified in relatively short order.

As for what happened to Judas, the Gospels offer differing accounts. Matthew has Judas accepting thirty silver coins for betraying Jesus (an echo of an Old Testament prophecy), but after his arrest, overcome with remorse, Judas throws the coins away and hangs himself. John depicts Judas prior to the betrayal as both the treasurer of the disciples, and an embezzler, thus already setting the stage for his later traitorous act. As described by Peter in the Acts of the Apostles (immediately following John’s Gospel) not only does Judas not undergo any remorse after Jesus’ death, he actually buys a piece of land with his money, but then one day suddenly falls down and has his ‘bowels gush out’, dying an agonizing death.

More than one historian or writer has noted the obvious: Judas appears to be a literary device, someone needed to provide a cause and effect link to initiate Jesus’ spectacular demise and resurrection. As John Shelby Spong noted, ‘The whole story of Judas has the feeling of being contrived.’14 His presence as an actual character is not convincing, if for no other reason than that his purpose for betraying Jesus is never really explained (apart from the standard profit-motive). Paul, whose writings actually predate even the oldest Gospel (Mark) by about twenty years, makes no mention of Judas at all. The conjectured missing ‘Q’ Gospel (believed by scholars to be the source of the common sayings found in Matthew and Luke that are not found in Mark) does not mention Judas either.

However, the entire New Testament narrative is weakly (or barely) corroborated in any 1st century historical records, so in that regard Judas is not much different from his master whom he betrays. His significance, as with Jesus, is archetypal, psycho-spiritual, and symbolic—a difference that does not diminish its power, despite what religious fundamentalists might assert. Before looking at the symbolic meaning of Jesus and Judas and their relationship, there is one more piece of history to mention, and it is the controversial ‘Gospel according to Judas’ that was discovered in Egypt around 1978 (the exact date is uncertain), but only made widely known to the public in 2006.

The Gospel of Judas

The mid to late 20th century was a highly interesting time to be alive for historians of Christianity, with two spectacular finds occurring in Egypt and Israel: the Gnostic Gospels recovered in Nag Hammadi in 1945, followed by the Dead Sea Scrolls in Qumran between 1947 and 1956. These in turn were followed by the Gnostic Gospel of Judas. The story of the discovery of the latter reads something like a cross between an Indiana Jones tale and a historian’s worst nightmare. In brief, the book—or ‘codex’ as ancient manuscripts are usually referred to as—was discovered in a cave in Egypt by some peasants, who sold it cheaply to a local dealer, who then tried to sell it via the potentially lucrative (but generally shady) international antiquities market. Over the next few decades this valuable document failed to find a permanent buyer for the steep price being asked for it. In the course of passing through a number of antiquities dealers and languishing in several inappropriate locations (including a safe deposit box and even a brief spell in a lawyer’s kitchen freezer), it degraded badly in quality. By the time it was finally purchased, properly safeguarded, and examined by manuscript restoration experts, it had crumbled to pieces and was almost beyond saving. However after several years of painstaking work the text was partially restored. All this was ultimately financed by the Maecenas Foundation in Switzerland, and later by the National Geographic Society, which in 2006 published its findings in its monthly magazine, and commissioned a television special and book, both broadcast and published in 2006.

The Gospel of Judas as discovered is in Coptic (the language used by the early Christians in Egypt). According to carbon-14 dating performed in 2005, the Gospel was estimated to have been written somewhere between 240 and 320 C.E.15 It is speculated (though not proven) to be a translation of an earlier Greek document written around 150 C.E. The Gospel is essentially a Gnostic interpretation of the relationship between Jesus and Judas. Parts of what it actually says are disputed—the original translation presented by the National Geographic team was attacked by other scholars, and viewpoints have arisen that appear to be diametrically apart. For example, the main version has it that Judas was not the betrayer of Jesus, but rather was his closest disciple and secret accomplice (something that is remarkably similar to the version of Judas presented in Martin Scorcese’s 1988 film The Last Temptation of Christ, based on the 1960 Nikos Kazantzakis novel). That version has been challenged by some scholars who find evidence that Judas in the Gospel is presented as a ‘demon’ who is indeed betraying Jesus. Yet another interpretation has him as being tricked by Jesus into believing that he was helping him.

The Gospel of Judas is controversial for other reasons; in some scenes, it depicts Jesus as bursting out laughing at his disciples, displaying behavior that seems surprisingly ‘edgy’ and ‘crazy wisdom-like’, unlike the conventional Sunday School image of Jesus as morally unblemished and showing a consistently saintly demeanor (although, even that view has to overlook the bizarre scene described in both Mark and Matthew where Jesus curses a fig tree, causing it to die, for no apparent reason other than that he was hungry and annoyed that the tree was barren).

As mentioned, a main thrust of the Gospel of Judas is that he is presented as an aid to Jesus, a disciple following instructions, and therefore as not a traitor. The Gospel also appears to imply that Judas was in fact the most advanced of the twelve disciples, thus following a classic Gnostic theme of inversion (compare, for example, the Gnostic idea that the Serpent of Genesis was a liberator and Yahweh a false god). In short, because the Gospel of Judas was written at a time when Gnostic ideas proliferated and were all part of a widespread multiplicity of competing Christian or quasi-Christian schools of thought, its prime value is more as a reflection of Gnostic ideas during its time. It cannot be taken to be some secret, ‘true’ statement about the role of Judas, if for no other reason than it was almost certainly written after both the canonical Gospels and the Gnostic Gospel of Thomas.

The idea of Gospels (such as that ascribed to Judas) being written down around 300 C.E., concerning events of the 1st century C.E., does not tend to represent much of significance for the casual observer—after all, whether 17 centuries or 20 centuries ago, both are long ago. Yet analogously, Isaac Newton’s groundbreaking Principia was written in the late 17th century—just over three hundred years ago from the time of this writing. Were nothing of Newton’s life and work recorded during his time, anything written about him now attempting to portray his life and ideas would be acknowledged to be hopelessly speculative. And this is why 3rd and 4th century Gnostic Gospels can only be taken as being representative of Gnostic traditions of that time. The entire story of Jesus is barely one step removed from myth as it is, even based on the late 1st century accounts of his life via the traditional Gospels. Writings such as the Gospel of Judas as ‘historical’ documents are therefore little better than a legend of a legend. (As mentioned, the Judas Gospel is speculated to derive from a 2nd century Greek text, especially since a ‘Judas Gospel’ was in fact mentioned by the 2nd century Church Father Irenaeus, but here the same problem remains—if true, what is being depicted are 2nd century Gnostic views, not 1st century history. To extend the analogy, compare 20th century ideas—whether from literature, politics, science, or spirituality—to those of the 19th century. A hundred year gap may not seem like much when it is viewed historically from far in the future, and may indeed be but a wink in time on the large scale, but it is in fact a vast gulf from the perspective of present time reality).

The whole idea of historical revisionism begins to miss the point when we seek to employ it as a tool to redefine a faith. The historical Jesus certainly has his place, and the work of recent scholars like Funk, Crossan, Borg, Mack, et al, can only be seen as both sincere and important. If nothing else, their work helps to put a well needed dent into the staid bulwark of unreasoning fundamentalism, and its more troublesome offshoots of intolerance and prejudice. To note openly, honestly, and intelligently the many internal contradictions in the Bible, and to attempt to excavate from its words the ‘real Jesus’, is not to diminish the spiritual symbolism and power of Christ, but rather to help purify the tradition of blind and insensitive dogma.

Ultimately, however, it is not the written words we need be exclusively fixated on; the need rather is to devote attention to our own presence, our own subjectivity, our own being. Joan Acocella, writing in The New Yorker about the Gospel of Judas, summed it up simply and concisely:

All this, I believe, is a reaction to the rise of fundamentalism—the idea, Christian and otherwise, that every word of a religion’s founding document should be taken literally. This is a childish notion, and so is the belief that we can combat it by correcting our holy books. Those books, to begin with, are so old that we barely understand what their authors meant. Furthermore, because of their multiple authorship, they are always internally inconsistent. Finally, even the fundamentalists don’t really take them literally. People interpret, and cheat. The answer is not to fix the Bible but to fix ourselves.16

Interpretation

Indeed, if we are sincerely interested in what it means to be a conscious human being, we must ultimately look to ourselves rather than to exploring the endless mazes of historical detective work (however interesting that might be). The observation to ‘fix ourselves’ is lucid and to the point. But how exactly do we fix ourselves? It is one thing to recognize this most essential of all issues, and another to understand what exactly it implies. In the case of Jesus and Judas, it is of course less about the two historical characters, whether or not they existed or what actually happened between them. That is the story, the myth, and carries real spiritual weight only inasmuch as we can understand what it has to teach us about ourselves.

An essential point to note, one that is both primary in all conflicted relationships and a main theme of this study, is contrast. A white spot appears whitest on a pure black background. The very negativity of the figure of Judas only serves to enhance the purity of Jesus, and vice versa. As archetypal figures, the two clearly need each other. The old expression is, ‘if Judas had not existed, God would have had to invent him’, but perhaps more to the point, we would have had to invent him, especially given how Jesus is portrayed to be. Judas is the fall guy, the ‘go-to’ man needed to keep us from examining ourselves. His act of treachery with Jesus is regarded as some sort of ultimate sin (and he is duly punished in literary canon, as in Dante’s violent treatment of him), and he has accordingly been equated with the worst stereotype of the Jew—self absorbed, greedy, secretive, untrustworthy, and ultimately traitorous. His figure lies at the roots of anti-Semitism, a cultural disease that reached its macabre culmination in the German concentration camps of the Second World War.

Judas keeps us from examining ourselves because as the ‘betrayer of God’, his treachery cannot be surpassed. However foul our deeds may be, his will always be fouler, and thus cause for projecting our own shadow elements ‘out there’, into the body of another, and so never having to fully assume responsibility for our own heart of darkness. Judas, betrayer of Christ, is the ultimate distraction, the ultimate convenience to aid in turning away from the abyss of our own ego.

That of course only addresses Judas the traitor, the Judas of what became orthodox Christian doctrine, the Judas who became inextricably linked with the stereotyped deceitful Jew. The Gnostic Judas, the Judas who appears to be presented in the Gospel of Judas, is merely another dimension of the traditional Judas; in essence, the inverse—instead of betrayer, now he is the ‘undercover agent’ of God. Either way, whether traitor or secret agent, he is made special—not in the common meaning of that word, but rather more in the sense of someone disconnected from the Whole.

As mentioned, Judas as traitor serves as an ultimate scapegoat, a Dante’s Inferno-suffering freak who always allows us a reprieve from gazing straight into our darkest potential, because by contrast, he is always darker. The inverse of this sort of scapegoat is one who has distinct status at the other end of the pole. This figure, the Gnostic Judas, is indispensable for other reasons—as Jesus says in the Gospel of Judas,

But you will exceed all of them. For you will sacrifice the man who bears me.17

The ‘sacrifice’ refers to the death of the body of Jesus, in turn liberating the spirit of Jesus. (This of course is a reflection of the Gnostic idea that the material body is flawed and irrelevant and need only be cast away—contrasted to the orthodox Christian view that Jesus’ physical body was itself resurrected). This sacrifice is brought about by Judas ‘handing over’ Jesus to the authorities, a phrasing that indicates he was simply doing Jesus’ bidding. But the wording ‘you will exceed all of them’, and other suggestive lines from the text, indicate, once again, a special status for Judas. He is, accordingly, the archetypal chosen one—whether as a betrayer, or as a secret agent.

Judas, in the tradition view of the canonical scriptures, is not just deceitful, he is demonic. This is at least according to two of the Gospels (Luke and John), which proclaim his possession by Satan:

Then Satan entered into Judas surnamed Iscariot, being of the number of the Twelve. And he went his way, and communed with the chief priests and captains, how he might betray unto them. And they were glad, and covenanted to give him money. And he promised, and sought opportunity to betray him unto them in the absence of the multitude. (Luke 22: 3-6, KJV).

And after the sop Satan entered into him. Then said Jesus unto him, That thou doest, do quickly. (John 13:27, KJV).

Standing behind Judas is Satan, and thus the polarity between Jesus and Judas is reduced to its primordial essence, the struggle between God and Satan—between good and evil. We see clearly here the dualism that is the very basis of consciousness in its relation to all that it experiences. That is, our very conscious identity is defined by contrast to that which appears to be different from us. Religious dualism—the notion of pure good vs. pure evil—was birthed originally as a political tool, a device to unify people, much as how Emperor Constantine sought to unify the fragmented Roman Empire in the early 4th century C.E., by convening the Nicene Council and establishing the absolute indivisibility between God and Jesus. This is then rendered into, If you are with us, you are with God; if you are not with us, you are not with God.

The psychopathology of this, on an individual level, is reflected in the division in human nature between the ‘realm of light’ and the ‘realm of dark’; between heaven and hell; between saint and sinner; between spiritual and material; between spirit and sex; between poverty and wealth. That then gives rise to the urge to condemn and attack whatever is different, as in racism, sexism, class discrimination, and the entire unholy panoply of prejudices conceivable by the human mind.

In the traditional view of Judas, not only is he traitorous in a fashion that is ultimately ludicrous (because of how it is so purposeless), but he is generally assumed to suffer eternal damnation as a result of his acts. He is apparently beyond forgiveness, and so he becomes a powerful symbol for the inner disconnection of a person from a part of their own being. He represents any part of us that we forsake, that we seek to eliminate by stuffing down into some remote ‘hell’, the realm of the irredeemable and unforgivable. As Solzhenitsyn once famously wrote in his Gulag Archipelago,

If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. And who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart?

If we destroy a piece of our own heart, we inevitably seek to destroy someone or something else as well. Ultimately we cannot but treat the world as we treat ourselves. Jesus’ famous injunction, imploring us to ‘love our enemies’, bears mention here:

Ye have heard that it hath been said, Thou shalt love thy neighbour, and hate thine enemy. But I say unto you, Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you; That ye may be the children of your Father which is in heaven: for he maketh his sun to rise on the evil and on the good, and sendeth rain on the just and on the unjust. For if ye love them which love you, what reward have ye? do not even the publicans the same? And if ye salute your brethren only, what do ye more than others? do not even the publicans so? Be ye therefore perfect, even as your Father which is in heaven is perfect. (Matthew 5:43-48, KJV).

But I say unto you which hear, Love your enemies, do good to them which hate you, Bless them that curse you, and pray for them which despitefully use you. And unto him that smiteth thee on the one cheek offer also the other; and him that taketh away thy cloak forbid not to take thy coat also. (Luke 6:27-36, KJV).

That these versions from Matthew and Luke are similar, but are not found in the older Mark Gospel, indicates to historians that they are sourcing from the missing ‘Q’ Gospel (‘Q’ is from the German Quelle, meaning ‘source’). The Jesus Seminar scholars rated these passages as being of a high probability words actually said by Jesus, particularly the directive to love your enemies.18 What does it mean to love our enemies? As Robert Funk put it, the saying is vintage Jesus, because ‘it cuts against the social grain and constitutes a paradox: those who love their enemies have no enemies.’19

‘Loving our enemies’ is, however, more than a clever psycho-social device to disarm those who are opposed to us. The injunction is not to be taken superficially, as some false piety, some phony holiness. It rather is reflective of some of the deepest wisdom of mystical tradition, perhaps nowhere echoed more clearly than in these lines from the famous little sourcebook of Chinese Taoism, the Tao Te Ching:

See the world as yourself.

Have faith in the way things are.

Love the world as yourself;

then you can care for all things (13).20

The key is to see the world as us. That is the key teaching at the core of most wisdom traditions, but the way Jesus tackles it is unique, and so starkly radical that it immediately grabs our attention. (As Ian Wilson wrote, ‘the power of Jesus is that he always contains an element of the unexpected.’) Jesus here represents our capacity to forgive in a profound and radical way, to ‘be big’ in the truest sense of those words. When we react petulantly, vengefully, we tend to diminish our spirit in some way. Not that passionate expression is to be denied—it is rather that our passion is to be re-directed back toward a love of truth. The surest way to do this is to stop wasting our passion, our life-force, on hating, on righteously condemning others, on ‘maintaining enemies’.

The passage quoted above from Matthew referring to God ‘making his sun to rise on the evil and the good, and sending rain on the just and the unjust’, gives a glimpse into the profound non-dualism found in the teachings of all deeply realized sages. Ultimate truth transcends human conventions of good and evil, of just and unjust, and embraces a much vaster totality in which nothing is disconnected from anything else. Significantly, the scholars of the Jesus Seminar rated as very unlikely to have occurred the entire matter around Judas—his being controlled by Satan, his betrayal of his master, his death. In referring to the scene of the Last Supper (in John) where Jesus tells Judas to ‘go quickly and do what you are going to do’, Robert Funk wrote,

All the words attributed to Jesus in this scene, in which he predicts his betrayal, are to be attributed to the storyteller’s craft…all the evangelists represent Jesus as foretelling his fate, with the result that, in some ultimate sense, he is in control of it. John specifically heightens this element by emphasizing Jesus’ choice of Judas as his betrayer.21

It is perhaps fitting that a group of scholars would arrive at such a view. Although analyzing the matter historically, not psycho-spiritually, the conclusion they arrive at is nevertheless consistent with what would be expected from a source of great wisdom; that is, a God-realized master who saw beyond duality, moral polarizing, and inner divisiveness, would have no place in his heart for an irredeemable scapegoat. In a heart that is infinite, none need be forgiven because none have been condemned. There is no Judas the traitor, only Judas, brother in spirit of Jesus.

The Esoteric View

That, at least, is the non-dualistic view (aided by historical scholarship). There is also a final perspective we can consider, and that is the so-called esoteric view. In this interpretation, the historical revisionism is dispensed with, the Gospels taken at face value, and a deeper, esoteric meaning to them is sought—a type of Gnostic re-interpretation. For example, as Richard Smoley points out in Inner Christianity, the four Gospels can be read as representing four distinct domains of human experience, those being the intellect (represented by Matthew), the emotions (Mark), the body (Luke), and the Spirit, or pure consciousness (John).22

In looking at the relationship between Jesus and Judas esoterically, the interpretation seems relatively straightforward, owing to the utter distinction between the two. Jesus clearly represents our True Self, what the Hindus called the atman, or what in some schools of Buddhism is known as the ‘buddha-mind’. He is pure awareness, the eternal and timeless Presence of consciousness. (This is sometimes called the ‘true I’, for convenience sake, however consciousness in this state is not well defined by the pronoun ‘I’, if only because it does not experience itself as distinct from the totality of existence).

Judas, then, would represent the part of our mind that rebels against truth, that is threatened by truth, and that accordingly seeks to undermine truth—to betray it, at all costs (or even for just thirty pieces of silver). The mystical text A Course in Miracles makes reference to the ‘murderous’ nature of the ego, as the part of our being that is so profoundly threatened by truth that it must silence it no matter what:

There is an instant in which terror seems to grip your mind so wholly that escape appears quite hopeless. When you realize, once and for all, that it is you you fear, the mind perceives itself as split. And this had been concealed while you believed attack could be directed outward, and returned from outside to within. It seemed to be an enemy from outside you had to fear. And thus a god outside yourself became your mortal enemy; the source of fear. Now, for an instant, is a murderer perceived within you, eager for your death, intent on plotting punishment for you until the time when it can kill at last.23

The ‘murderer within’ is vivid symbolism for all guilt and self-loathing, and all fear of relinquishing control—the control of our own identity, and the fear of being dominated, controlled, killed, by something bigger. Judas represents our fear of light and truth and life—the ‘Way’ represented by Jesus. Judas is the part of us that fears being ‘killed’ by truth, and so seeks to kill it first.

Truth is a fire and it does, in a very real sense, ‘kill’ us—that is, the part of us that is false, illusory, what the Buddha referred to as our attachments, and the entire constructed edifice of the personal self that seeks to wall itself off from the true reality of the infinite. In that sense, the ‘murderous’ and traitorous face of the mind encompasses more than just Judas, it is also represented by all that fear truth, such as in Peter’s denying of Jesus shortly after his arrest, and of the failure of any of the twelve disciples to attend the crucifixion.

Ultimately, we are all cowards in the face of radical, uncompromising spiritual truth, and if we are not busy running from it, we are involved in undermining it. That does not mean, however, that we need crucify ourselves for this fact. Such a punishment has already been done; we need not repeat it. Our task is, rather, to ‘love our enemies’—in this case, our ‘inner Judas’—to look deeply into the face of fear, to summon compassion for it, and to recognize it as our ultimate teacher. Only then do we rescue Judas, and recognize him as brother in Spirit.

Notes

1. Vivian Green, A New History of Christianity (Leicester: Sutton Publishing, 1998), p. 33.

2. Robert Funk, Ray Hoover, et al., The Five Gospels: The Search for the Authentic Words of Jesus (New York, Polebridge Press, 1993), pp. 2-3.

3. Ibid., p. 5.

4. See, for example, G.A. Wells, The Jesus Myth (Chicago: Carus Publishing Company, 1999), pp. 114-177; or Robert Funk, Honest to Jesus: Jesus for a new Millennium (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1996), pp. 292-296; or, Uta Ranke-Heinemann, Putting Away Childish Things: The Virgin Birth, the Empty Tomb, and Other Fairy Tales You Don’t Need to Believe to Have a Living Faith (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1994); or Burton Mack, Who Wrote the New Testament? The Making of the Christian Myth (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1995); or the works of Bishop John Shelby Spong. Andrew Harvey gives a good general summary, for the non-specialist reader, of many of the conclusions of historical biblical scholarship in his Son Of Man: The Mystical Path to Christ (New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam, 1998), pp. 5-6.

5. Ian Wilson, Jesus: The Evidence (London: Orion Publishing Group, 1998), p. 43.

6. There are many detailed critical deconstructions of these stories. For a concise (and witty) overview of the contradictions and likely fabrications in Luke and Matthew concerning the birth of Jesus, see Ranke-Heinemann, Putting Away Childish Things, pp. 5-33.

7. John Dominic Crossan, Jesus: A Revolutionary Biography (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1994), pp. 5-6.

8. See, for example, John Shelby Spong, Born of a Woman: A Bishop Rethinks the Virgin Birth and the Treatment of Women by a Male-Dominated Church (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1992), pp. 76-80.

9. Wells, The Jesus Myth, p. 115.

10. Ranke-Heinemann, Putting Away Childish Things, p. 63.

11. Hans Kung, Christ Sein (Zurich: Ex Libris), p. 441.

12. According to Tibetan documents he taught one of his own students, the legendary Yeshe Tsogyal (757-817 C.E.), how to revive dead people, which she is reputed to have done. See Erik Hein-Schmidt, Advice From the Lotus-Born (Hong Kong: Rangjung Yeshe Publications, 1994), p. 183. For a further recounting of fantastic miracles by Tibetan Buddhist monks, miracles far surpassing, in science fiction-like wildness, anything credited to Jesus in the New Testament, see Keith Dowman, Sky Dancer: The Secret Life and Songs of the Lady Yeshe Tsogyal (London: Penguin/Arkana, 1989), pp. 112-113.

13. Here again, despite what many Christians believe, even this miracle is not unique in world spiritual traditions. The Hindu tradition in particular has many legends of ‘yogi-saints’ living in the Himalayas who have maintained ‘light-bodies’, or in Christian terms, ‘resurrection-bodies’, for thousands of years. A good example can be found in Paramahansa Yogananda’s Autobiography of a Yogi, wherein he recounts the legends of the fabled ‘Yogi-Christ’ of the Himalayas, a saint named Mahavatar Babaji, who is reputed to have maintained a ‘light body’ in the Himalayas for at least two thousand years.

14. John Shelby Spong, The Sins of Scripture: Exposing the Bible’s Texts of Hate to Reveal the God of Love (San Francisco: HarperCollins, 2005), p. 203.

15. Tobias Churton, Kiss of Death: The True History of the Gospel of Judas (London: Watkins Publishing, 2008), p. 57.

16. www.newyorker.com/arts/critics/atlarge/2009/08/03/090803crat_atlarge_acocella?currentPage=all (accessed July 24, 2010).

17. Rodolphe Kasser, Marvin Meyer, Gregor Wurst, editors, The Gospel of Judas, Second Edition (Washington D.C.: National Geographic Society, 2008), p. 51.

18. Funk, The Five Gospels, pp. 145-147.

19. Ibid., p. 147.

20. Stephen Mitchell translation, Tao Te Ching (New York: HarperPerennial, 1988).

21. Funk, The Five Gospels, p. 448.

22. See Richard Smoley, Inner Christianity: A Guide to the Esoteric Tradition (Boston: Shambhala Publications, 2002), pp. 120-136. Smoley’s idea is indeed provocative, although it does not address the Gospel of Thomas, which although non-canonical, is considered by many scholars to be of equal importance to the four traditional Gospels.

23. A Course in Miracles, Workbook lesson #196, paragraphs 10-11. (Glen Ellen: Foundation For Inner Peace, 1992), p. 375

Copyright 2010 by P.T. Mistlberger, all rights reserved.