The Mystery of Gurdjieff’s Birth

(Note: An abbreviated form of this article appears as Endnote

#4 to Chapter 2 of my book The Three

Dangerous Magi: Osho, Gurdjieff, Crowley).

Gurdjieff arriving in the United States in January, 1924 -- aged 58, 52, or 47?

The year of birth of a notorious early 20th century magus and unorthodox ‘teacher of dance’ may seem only a matter of interest to esoteric historians, but in Gurdjieff’s case the whole matter is a fitting metaphor for the mystery of the man himself. Gurdjieff ‘officially appeared’ in 1912 in Moscow. When a 37 year old P.D. Ouspensky met him three years later, he described him as ‘no longer young’. That of course is a description meaning little; indeed, some people show their age as much as others intentionally or unintentionally don’t.

Prior to 1912 Gurdjieff’s history is largely apocryphal, the sole source of information being his own book Meetings With Remarkable Men (published posthumously in 1963), a work most agree is at the very least embellished autobiography.

Gurdjieff had different passports over the years that gave different birth dates. Up to around 1990 the most common years given for his birth have been 1872 and 1877, although few writers citing these dates have provided any justification for doing so. James Moore, in his comprehensive biography Gurdjieff: Anatomy of a Myth, argued persuasively for 1866, and since the publication of Moore’s book in 1991, this date seems to have overtaken others (for example, John Shirley cites it in his 2004 primer on Gurdjieff), based on these points:

A. Gurdjieff claimed to be 78 years old in 1943, and 83 years old in 1949 (the year of his death).

B. The photos of him taken

shortly before his death (in 1949) seem (to Moore) more like a man in his early

80s, rather than a man in his mid or early 70s.

The Andrieux Portrait, taken in 1949. Moore claimed this pictured is 'redolent of a man of 83',

consistent with a birth year of 1866.

C. Gurdjieff claimed that when he was a seven year old boy his father’s cattle herd was wiped out by a plague. There was in fact a disastrous outbreak of cattle disease (rinderpest) in 1872-73 in Asia Minor.

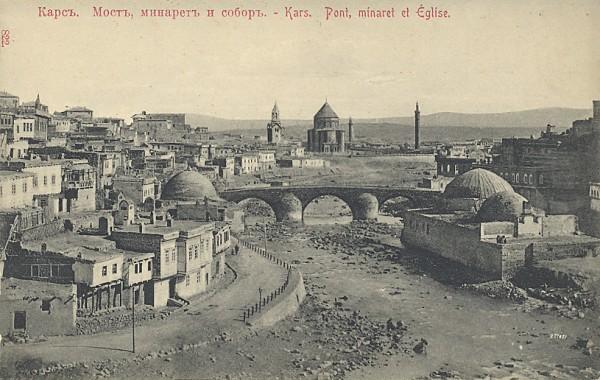

D. Gurdjieff and his family arrived in the Turkish city of Kars not long after a Tsarist military victory in 1877, at a time when Gurdjieff already had four younger siblings.

E. This point is not mentioned by Moore, but it is worth listing: when Ouspensky first met Gurdjieff in 1915 in Moscow, he described Gurdjieff as a man appearing “no longer young”. If Gurdjieff was born in 1877, he would have been 38 at the time of meeting Ouspensky; if born in 1872, then 43; and if born in 1866, he would have been 49. I think it safe to assume that “no longer young” fits more closely with 43 or 49 rather than 38. Ouspensky himself was 37 at the time of this meeting; it is unlikely he would describe someone around his own relatively youthful age as “no longer young.”

Gurdjieff did have a passport that gave his birth year as 1877, but as mentioned he had several passports, some with different dates—one indicated as early as 1864—and all of them he burned in 1930 before one of his trips to America (see Patterson, Struggle of the Magicians, p. 216). While Moore’s points are interesting, they are not foolproof, and he does appear to make one mistake. The counter-views are as follows:

A. The fact that Gurdjieff claimed a certain age for himself means little, as he was commonly known to have no fear of saying whatever he felt like saying at any given time, regardless if it was based in fact or not. Moore’s first argument, that Gurdjieff claimed to be 78 in 1943, does not add up arithmetically—78 in 1943 would mean he was born in either 1864 or 1865, not 1866. And this appears to be Moore’s mistake, because he states that one passport of Gurdjieff’s listed his year of birth as the “wildly discrepant 1864”—when Gurdjieff himself apparently stipulated this year (or 1865) when describing his age in 1943. [Note: I’ve had occasion to reassess this comment of mine, and will adjust it in the 2nd edition of the book, owing to the fact that Moore reports that Gurdjieff made this remark on December 16, 1943, and claimed to have been born in January. Accordingly, he may have been just a few weeks shy of his next birthday, and conceivably could have referred to himself as ‘78’, even if technically still 77, in December of 1943, if in fact he was born in January of 1866.] Further, according to J.G. Bennett in his autobiography, he reports that Gurdjieff in January of 1949 claimed that he was now 80 years old. That would make his birth year 1869, not 1866. Bennett indicates that he believed Gurdjieff was not telling the truth, that in fact he was “a good deal younger.” (See J.G. Bennett, Witness: The Autobiography of John Bennett (Wellingborough: Turnstone Press, 1983), p. 251.

B. The photos of Gurdjieff supposedly looking 83 years old could easily be pictures of a 72 or 77 year old man who had lived a very rugged life (which was certainly true in Gurdjieff’s case). This was further suggested by the doctor who performed the autopsy on Gurdjieff’s body, declaring that he should have died years before as most of his organs were in very poor shape.

C. Some video of Gurdjieff surfaced in the early 2000s on the Internet—mostly short silent clips of him interacting with students in public places during the last years of his life (1947-49). Examining those videos it is surprising to think that the short, portly man (as he was at the time) is in his early 80s. Very few overweight people live into their 80s. He moves around in a fairly nimble fashion that seems a bit quick for an 82 or 83 year old. (But he was, after all, a “teacher of dance” as he liked to describe himself, and was clearly a very rugged man, so it is not impossible).

J.G. Bennett favored 1872. In his book Gurdjieff: A Very Great Enigma, he wrote:

So far as I myself can make out from various sources, from what he himself and his family have told us, it does seem probable that he was born in 1872, in Alexandropol, and that his father moved to Kars soon after it was taken by the Russians, that is to say, somewhere about 1878, when he was six or so years old. (Bennett, 1963).

The Armenian town of Gyumri (named Alexandropol when Gurdjieff was born there).

About ten years after that Bennett wrote his loose biography of Gurdjieff (Gurdjieff: Making a New World) and had this to say:

The date of Gurdjieff’s birth, as shown on his passport, was December 28th, 1877. He himself said he was much older and also claimed that he was born on January 1st old style. I have found it hard to reconcile the chronology of his life with the date of 1877, but his family asserts that this is correct. If this is so, he began his search at the early age of eleven, because he refers to the year 1888 as a time when new vistas opened up to him. He first went to Constantinople in 1891. He says he was a “lad” at the time of this journey, so the dating is not obviously inconsistent. Nevertheless it does seem strange that, if he was born in 1877, he should not have mentioned that this occurred during the Russo-Turkish war. (Bennett, 1973).

Despite these misgivings, Bennett goes on to state:

In October of 1877, the city [of Kars] was in its last throes, and the tsar sent his brother, Grand Duke Nicholas, to lead the final assault. With an overwhelming superiority in numbers and armaments, the defenses were overrun on the night of November 17-18. Six weeks later, Gurdjieff was born in Gumru, already renamed Alexandropol in honor of the tsar’s father. (Bennett, 1973).

So apparently Bennett either forgot that a decade before he’d declared Gurdjieff’s probable year of birth as 1872, or he changed his view. Jeanne de Salzmann, Gurdjieff’s chief administrator and designated leader of the world-wide Gurdjieff community at his death in 1949, held to 1877.

All this is contradicted yet again in another of Bennett’s books, his 1961 autobiography (Witness: The Autobiography of John Bennett), where he writes of his first meeting with Gurdjieff in 1920:

It was only when he removed his kalpak after the meal that I saw his head was shaved. He was short but very powerfully built. I guessed that he was about fifty, but Mrs. Beaumont was sure that he was older. He told me later that he was born in 1866, but his own sister disputed this and affirmed that he was born in 1877. His age was as much as an enigma as everything else about him. (Bennett, 1961, p. 55).

That particular anecdote does not bode well for the 1866 date, as a man’s sister would generally have little incentive for lying about such a thing, nor would she be likely to make such a large error as eleven years when estimating her older brother’s age. (Although it is conceivable, if she was incompetent with arithmetic—i.e., an honest mistake).

Finally, it bears mentioning here that one of the better more recent chroniclers of Gurdjieff and his Work, William Patrick Patterson (who has written several books and produced three good videos on the matter), weighs in with his vote for 1872. In the notes section of his Struggle of the Magicians, he remarks:

I believe that Gurdjieff was born—not in 1877 nor in 1866—but in 1872. This is based on dates Gurdjieff gives in Meetings with Remarkable Men. (Patterson, 1996, p. 216).

He then goes on to provide a series of arguments based on events in Meetings, which are essentially the following:

1. In 1888 Gurdjieff first witnessed the Yezidi ‘trapped’ in a ‘magic circle’. This was also the year that he drank (vodka) for the first time. His exact words were ‘It must be said that that year I had already begun to drink, not much, it is true, but when invited to so, as sometimes happened, I did not refuse’ (Meetings, p. 67). These would seem questionable words to use for a man already 22 years old (which would be the case if Gurdjieff was born in 1866), all the more so given that, generally speaking, further back in time people ‘grew up’ faster. If born in 1872 he would have been 16 when he ‘already began to drink, not much, it is true…’, a more likely age for such a choice of words).

2. Patterson claims that it

was in 1888 that Gurdjieff was smitten by a young girl of 12 or 13; his friend

Piotr Karpenko was also infatuated with the same girl, and the two young men

eventually did battle over her, culminating in an absurdly risky duel.

Patterson reasons that such events would be unlikely for a 22 year

old man, but would be likely for a 16 year old boy.

3. According to Meetings, one of Gurdjieff’s important early mentors, Father Evlissi (Bogachevsky), arrived in Kars in 1886, the year after Gurdjieff’s sister died and ‘he first became interested in abstract questions’. Patterson concludes that this is all more likely for a 14 year old boy, than a 20 year old man.

Kars, the city in northeastern Turkey where Gurdjieff grew up.

Another point not mentioned by Patterson: Gurdjieff claimed that in 1888 he was given a job ‘ordered by a neighbour’ to fashion a monogram on a shield to commemorate the neighbour’s niece’s wedding. While doing this work, Gurdjieff remarked on the ‘children playing nearby’ who made ‘incredible noise and commotion’ but ‘who never disturbed my work’. If true, that event argues strongly against the possible 1877 birth year, as it is doubtful that an 11 year old boy would regard a situation in such a way.

However as I neglected to mention in the book, Patterson’s observations are not foolproof either.

1. While unlikely, it’s not impossible that Gurdjieff did not begin to sample alcohol until age 22.

2. While by today’s standards a 22 year old man infatuated with a 12 or 13 year old girl might seem peculiar, young girls in older times often married young (Juliet, the archetypal lover of Shakespeare’s iconic play, is only 13). Further, although Patterson claims that Gurdjieff had his ‘silent romance’ with this girl in 1888, evidence for this date is lacking; in Meetings, the chapter on Karpenko (pp. 199-224) in which this ‘romance’ is mentioned, fails to specify a year.

Amusingly, Patterson also notes that Olga de Hartmann, a close student of Gurdjieff’s, always believed that he was older than the 1877 date, but was unable to prove it—despite the fact that her own passport listed her year of birth as 1896 when in fact she was born in 1885. At any rate, to me the most logical date does indeed seem to be something closer to 1872, particularly judging from the video clips taken of Gurdjieff’s last years. Bennett, though originally promoting this year, gives no real argument for it. Patterson (for 1872) and Moore (for 1866) seem to be the only researchers who provide solid arguments for their dates.

This business of attempting to date Gurdjieff’s life is of course all a good metaphor for the natural desire to give shape to the amorphous nature of personal identity. Few made the 'amorphous nature of personal identity' more apparent than Gurdjieff himself. Obviously it doesn’t ultimately matter when exactly he was born, but if nothing else reflecting on our attachment to the story of an individual can yield insight into the attachments we have to our own ‘personal story’.

Copyright 2011 by P.T. Mistlberger

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Osho, John Dee, and the Greatest Library in the World

(The following article appears as Appendix IV in my book The Three Dangerous Magi).

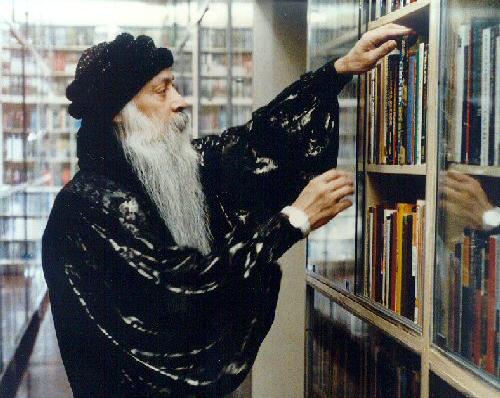

Osho was without question the most literate Eastern guru in memory—and possibly the most well read mystic ever. From his teenage years he began collecting books and by the time he was twenty years old he was already very well read. Throughout his college years both as an undergraduate and later as a philosophy professor his collection continued to grow.

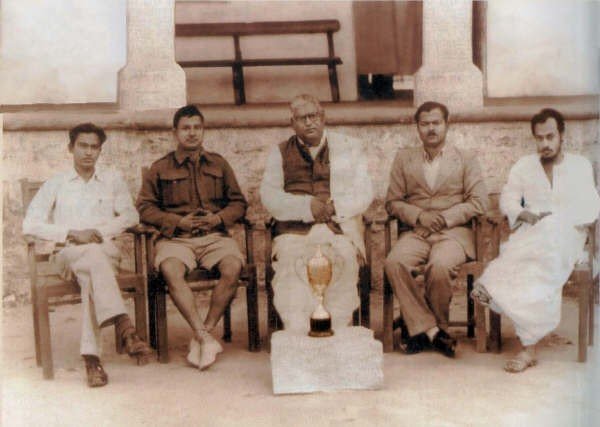

A rare early picture of Osho (seated, with his patented leg-cross, on the far right in white robe) from his days as a young graduate student of philosophy, approximately 1955.

Near the end of his life in the late 1980s it was estimated to be around 100,000 volumes. Osho himself mentioned the figure of 150,000. The Danish professor Pierre Evald, who is also a disciple of Osho’s, did a study of Osho’s library and estimated the actual number to be closer to 80,000.1 He reports that about 70,000 of these have been read, signed and dated by Osho. The remaining 10,000 have been gathered since 1987 at which point Osho was no longer reading (he said in an interview in 1985 that he’d basically stopped reading in 1981).

For a private library the figure of 80,000 is extraordinarily large (and indeed, Evald suggested that it may be the largest private collection in the world). As a point of comparison an entire main library in a mid-sized city might hold around a million books, barely ten times more than Osho’s collection.2 The most important library of the ancient world, in Alexandria in northern Egypt, is estimated to have had a collection of several hundred thousand scrolls. However an entire piece of writing—what we would now call a “book”—could take several scrolls to contain and so the actual number of “books” in the Alexandria library would have been smaller, perhaps around 100,000, similar to the size of Osho’s library. The Alexandrian library was famously destroyed in a series of calamities, most notably in what are suspected to have been burnings instigated by Julius Caesar (accidentally) a fourth century Christian bishop (intentionally) and a seventh century Muslim Caliph (intentionally).

In England in the late 16th century during the time of Queen Elizabeth I and Shakespeare, the largest library in the country (and possibly all of Europe) belonged to the queen’s court astrologer, advisor, and magus, John Dee. He had around 4,000 volumes.3 Much of this collection was eventually destroyed by a mob convinced that Dee was a conjurer of spirits. He was, amongst other things, but what today would be regarded as “channeling” unfortunately was in those days highly suspect and possible grounds for being burnt at the stake. Dee survived, but alas, many of his books didn’t.

To give some idea of the impressiveness of Dee’s collection, the main library at Cambridge University in the late 16th century only had about 450 books in all.4 In fact Dee’s library was the true academic center of England at his time and was known to have received visits from a number of notable people, including the queen herself. As for content his collection reflected the fact that he was a Renaissance magus: he had works on science (he was one of the leading mathematicians, cartographers, and navigators of his time), as well as the complete works of the major Greek philosophers, the Neoplatonists, poetry, theology, alchemy, magic, and so on.

Osho may not have been a conjurer of spirits (at least in the classic sense) and nor was India’s head of state sufficiently open to use him as an advisor5, but one thing he did have in common with Dee was that he was a man with a universal outlook and (especially in his younger years) an interest in reading anything of quality he could get his hands on.

Osho said that for much of his life he read twelve hours per day, sometimes eighteen hours.6 This again is reminiscent of Dee who famously recorded that he allowed himself only four hours sleep a night, two hours for eating and other essentials, and eighteen hours a day for study. Assuming that Pierre Evald’s estimate is accurate and that Osho had read about 70,000 volumes of his collection; and assuming that Osho was reading consistently from around ages fifteen to fifty (that is, around 1946 to 1981 when he gave up reading) then that would suggest that in roughly 35 years he read about 2,000 books per year—or, around six books per day. And when it’s considered that he did not actually retain a copy in his collection of every book he read—Evald reports that there are libraries in northern India that still have Osho’s name on them as the only person who ever borrowed the book—then we can safely assume that the number he read is even higher. Osho was a known speed reader and was reported by those close to him who used to supply him with books that he was devouring between ten and fifteen per day. So the above figures would indeed seem to be legitimate.

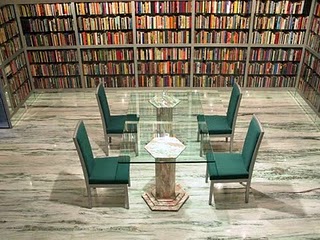

A central chamber in Osho's library at his ashram in Pune, India

Any way it is looked at Osho’s accomplishment in this realm is extraordinary. Evald—in his critically researched and balanced study—simply calls him “the greatest bookman of India and the most voracious reader worldwide in the 20th century.” He further claims that Osho actually read between 150,000 and 200,000 books in his lifetime. That indeed translates as his followers claimed to between twelve and fifteen books a day over thirty-five years. Even if we use a “low” figure of ten books per day this works out to about a book per hour of available reading time. The average book is about 60,000-80,000 words long. This means Osho’s speed reading amounted to at least 1,000 words per minute. The average reader can comprehend and retain about 150-300 words per minute; high achievers can approach 600 words per minute. Speed readers however are capable of spectacular rates: the current record holder is a man named Howard Berg who can read (if you can believe it) 25,000 words per minute.7 He has been repeatedly tested on this and demonstrated his ability to actually recall in detail what he reads. That rate is sufficient to read the Bible in half an hour and Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace in just over 20 minutes.

Sam, in Life Of Osho,

reports that in the mid-1970s Osho was a “recluse.” He ominously notes, “After

the morning lecture he went back into his house…and stayed alone in his room.

No one knew what he did there.”8 Perhaps the mystery is hereby

solved. However the most remarkable paradox about Osho has always been the

substance of his teachings: emphasizing Being, heart, mindfulness, the body—but

never the intellect. And yet there he was, with one of the most extraordinary

intellects of any mystic ever—and a bibliophile to top it off.

Shortly before Osho died he gave specific instructions for

his library: no more than three books to be lent out at any given time. It

appears as if he left his body with at least one remaining worldly

attachment.

Notes

1. Pierre Evald’s is the only serious attempt at a scholarly study of Osho’s library that I am aware of. His excellent paper can be viewed at www.pierreevald.dk/osho.php

2. The largest library in the world is the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. As of 2008 it holds around thirty-two million books.

3. Peter French, John Dee: The World of an Elizabethan Magus (New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1987), pp. 43-44.

4. Ibid., p. 44.

5. That would suggest that either Queen Elizabeth was unusually open-minded for a head of state, or that John Dee was a tame fellow compared to Osho. Somehow I more suspect the latter. Although granted, Osho did not have to worry about being roasted at the stake (at least, not that type of stake). Dee was considered fortunate to escape the Inquisition.

6. www.oshoworld.com/biography/innercontent.asp?FileName=biography6/06-10-library.txt

7. www.docstoc.com/docs/10454192/Speed-Reading-Study

8. Sam, Life Of Osho (London: Sannyas, 1997), p. 37.

Copyright 2009, by P.T. Mistlberger, all rights reserved.

_________________________________________________________________________________

The Tale of a Painting

by P.T. Mistlberger

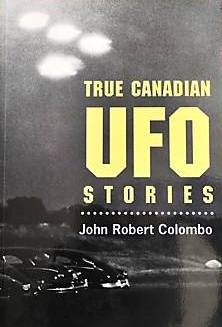

In late July of 2011, I was checking some online material in relation to a chapter of a book I’d published in late 2010 (The Three Dangerous Magi). The chapter concerned the legendary ‘encounter’ between the two famed 20th century magi, G.I. Gurdjieff (1872?-1949) and Aleister Crowley (1875-1947). In so doing I accessed a blog that had been written on the ‘leap-year day’ of February 29, 2008, by one John Robert Colombo1. The blog featured a photo of British historian Ronald Hutton and some discussion of his recent book The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft. In addition, the blog made mention of the legendary Gurdjieff-Crowley encounter of 1926. I had originally looked at this blog in the summer of 2009, while knee-deep in research for my book, and filed away an intention to contact the author of the blog when the time was more favorable for that.

I enjoy collecting books, a practice I’ve sporadically continued for the past thirty years (interrupted by a couple of periods of extended travel in the 1980s, during which I gave away or sold most of my collection at those times). A few weeks prior to re-checking John Robert Colombo’s blog I absent-mindedly picked up a book in a used bookstore titled True Canadian UFO Stories. In all honesty I did not pay much attention to the book, let alone the name of the author, when I picked it up. (UFOs and related matters have long been a side-line interest of mine). I bought the book because the subject matter (Canadian UFO lore) is relatively rare, and the book itself, though it had been printed in 2004, was in immaculate condition (clearly whoever had owned it, had not read it).

As matters had it, when I got home I tossed the book on my night table but did not get around to opening it for some time. I was too involved in work-matters, and was also well into the writing of a new book on the modern cultural distortions of the esoteric wisdom traditions (a work that has involved a large amount of research into classical ‘horror’ subjects such as monsters, werewolves, ghosts, aliens, and so forth). But one evening in late July—two years after first discovering it—I accessed John Robert Colombo’s Gurdjieff-Crowley blog again, noted at the bottom of it how he invited any with ‘additional information’ on this encounter to contact him, and proceeded to send him an email, as I was confident that my research into this ‘meeting of the Magi’ was as least as extensive, if not more so, than any attempted up to this time.

I received a prompt and friendly reply from

JR, and then decided to see if there was a Wikipedia entry on him. What I

discovered left me somewhat embarrassed, because despite being a fellow-Canadian

and a reasonably literate man of 52 years of age, I had never heard of Colombo

before, at least by immediate conscious recall. And yet according to his Wiki

page, and to the substantial documentation on his own website, he is one of Canada’s more

prolific, and interesting, authors. (My lame excuse here being that as a

Canadian having lived most of my life a few miles from the America border, I am

saturated with American cultural content—I’ve read more of William Faulkner

than I have of Robertson Davies—and I get my news from NBC and CNN, not CBC.

But I have read Farley Mowat and some

of Pierre Berton, so I am not a complete cultural turncoat). John Robert Colombo

has been involved in the publication of some two-hundred books, as author,

compiler, editor, and translator. Although chiefly a poet, I still think he compares

favorably to a Canadian version of Isaac Asimov (1920-1992), the famed American

science-fiction author who was renowned for his broad scope of interests, accessible

writing style, and prolific and intelligent literary output.

To return briefly to the matter of the book

on Canadian UFO stories on my night table. A few days after some

correspondence with JR, I was preparing to sleep one night when I decided to

reach for the book, and as is my usual habit, do some reading before turning

out the lamp. To my surprise I beheld the name of the author of the UFO book:

the same John Robert Colombo. There was definitely no getting away from this

author that particular week. (I cracked open the book to one Twilight

Zone-esque tale that involved a young family driving down a placid highway road

in Saskatchewan in 1964 when their car suddenly levitated on one side into an

utterly impossible position, maintained this for a while, then slowly

rebalanced itself—all on a perfectly flat highway with no apparent natural way

for this to occur. The title of the chapter was the wonderfully unadulterated The Car Started to Rise Up. It’s these

kinds of stories that are always such a good shakeup to our staid ‘reality

tunnels’, as Robert Anton Wilson called them).

To return briefly to the matter of the book

on Canadian UFO stories on my night table. A few days after some

correspondence with JR, I was preparing to sleep one night when I decided to

reach for the book, and as is my usual habit, do some reading before turning

out the lamp. To my surprise I beheld the name of the author of the UFO book:

the same John Robert Colombo. There was definitely no getting away from this

author that particular week. (I cracked open the book to one Twilight

Zone-esque tale that involved a young family driving down a placid highway road

in Saskatchewan in 1964 when their car suddenly levitated on one side into an

utterly impossible position, maintained this for a while, then slowly

rebalanced itself—all on a perfectly flat highway with no apparent natural way

for this to occur. The title of the chapter was the wonderfully unadulterated The Car Started to Rise Up. It’s these

kinds of stories that are always such a good shakeup to our staid ‘reality

tunnels’, as Robert Anton Wilson called them).

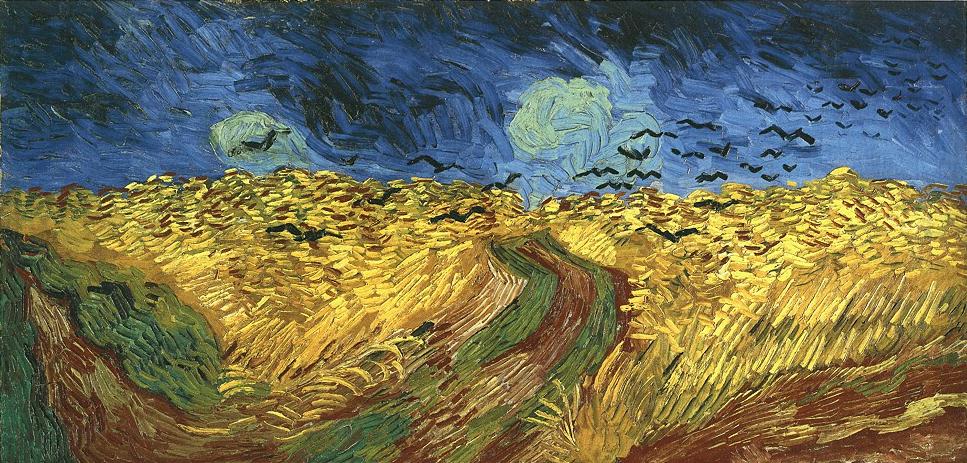

As part of JR’s reply email to me, he made

casual mention of an ‘original watercolor’ he owned by Aleister Crowley, and

included a jpeg attachment of the painting. Art runs somewhat in my family; my

father has painted (oil and acrylic) for some 60 of his nearly 80 years on

Earth, and in his retirement has been quite prolific. A number of his works

hang on the walls of restaurants and small businesses in his town (Ottawa). I have also done

some painting, though not as much as I would like over the years, owing to lack

of time. My personal preferences have inclined toward the Dutch: Rembrandt and

Van Gogh, in particular. A highlight of one of my trips to the Middle East and

North Africa I made in the late 1990s was a stopover in Amsterdam during which I was able to see the

works of these masters up close. (And, like many tourists seeing Van Gogh’s

canvasses for the first time, was surprised at how small they were).

Back in my university years I’d once written

an essay on Van Gogh’s Wheatfield With

Crows, in which I’d argued that the impossibility of determining whether

these crows were heading toward the viewer, or away from him, was a solid

metaphor for the uncertainties of perception and psychological perspective in

general. (The essay had the merit of at least impressing my professor at the

time, a fact perhaps dampened by the reality of his love of the bottle. One

never knew if he was marking one’s efforts whilst sober or not).

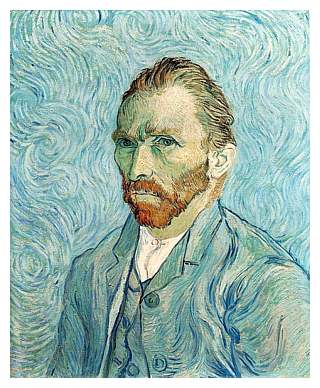

That said, it had been Van Gogh’s

self-portraits that I’d long found most haunting. Rembrandt, though of a

completely different style, imbued many of his portraits with a similar

quality, what I could only describe as ‘brooding intensity’. I’d long thought

that this was perhaps best captured in his Man With The Golden Helmet—but

discovered that this painting was determined by experts in the mid-1980s to

probably not have been painted by Rembrandt after all, but presumably by one of

his students. As Otto Friedrich lamented upon finding this out, ‘Sometimes it

seems that all of education consists of first learning things and then learning

that they are not true’. As has been pointed out by some who have studied the matter, sales of prints of the iconic Golden Helmet Man declined drastically as it became known that this was probably not a Rembrandt work -- despite the fact that the work is obviously both powerful and exquisitely executed -- an interesting testament to our fixation with personalities, and subsequent glorification of whatever it is they lend their hand to.

That said, it had been Van Gogh’s

self-portraits that I’d long found most haunting. Rembrandt, though of a

completely different style, imbued many of his portraits with a similar

quality, what I could only describe as ‘brooding intensity’. I’d long thought

that this was perhaps best captured in his Man With The Golden Helmet—but

discovered that this painting was determined by experts in the mid-1980s to

probably not have been painted by Rembrandt after all, but presumably by one of

his students. As Otto Friedrich lamented upon finding this out, ‘Sometimes it

seems that all of education consists of first learning things and then learning

that they are not true’. As has been pointed out by some who have studied the matter, sales of prints of the iconic Golden Helmet Man declined drastically as it became known that this was probably not a Rembrandt work -- despite the fact that the work is obviously both powerful and exquisitely executed -- an interesting testament to our fixation with personalities, and subsequent glorification of whatever it is they lend their hand to.

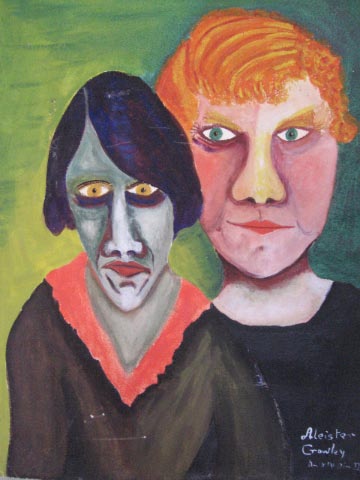

The Crowley watercolor JR sent along was an interesting study of two people—at first glance, I assumed them to be a woman and a man—rendered in Crowley’s inimical style, featuring (perhaps) some sort of intense blend of impressionism, semi-surrealism, and an almost child-like simplicity. I’d assumed upon this first glance that the woman was Leah Hirsig, Crowley’s lover and spiritual partner from approximately 1919 to 1924. I guessed the man to be Cecil Russell, but after posting mention of the painting at the chief Aleister Crowley discussion website, LAShTAL.com, the general feedback was that this was in fact a portrait of two women. Various speculations were ventured, a reasonable one being that the women were Hirsig and Jane Wolfe, the latter an established silent film star of Hollywood’s earlier years who became Crowley’s apprentice (and one of his more successful ones, it should be noted).

With JR’s permission I forwarded the jpeg

of Crowley’s watercolor to Richard Kaczynski, who is the current pre-eminent

Crowley biographer (his 2010 revised version of Perdurabo: The Life of Aleister Crowley, being a truly encyclopedic chronicle of the

Beast’s journey, unlikely ever to be surpassed). Richard did not immediately

recognize it, but suspected it was a significant find and quite possibly

authentic. He then forwarded mention of the painting and the image to William

Breeze, the current custodian of Crowley’s

estate (and the Frater Superior of Ordo Templi Orientis, a.k.a. Hymenaeus

Beta). Breeze took an interest in the matter, and soon identified the painting

as having been crafted by Crowley likely in early 1918. He had a photo of the

work, a monochrome copy of which, as it turned out, was already in the Harry Ransom

Center at the University

of Texas, in Austin. (This latter was also independently

confirmed by a poster at LAShTAL. Another poster then matched the color

jpeg with the monochrome copy in Austin,

and the identity of the painting was confirmed). The signature is accompanied

by a blurry dating; a close up magnification of this dating appears to indicate

Anno XIV, followed by the astrological symbols for Sun in Gemini. That would

suggest 14 years after 1904 (the date Crowley

received The Book of the Law), i.e.

1918. Sun in Gemini falls sometime between May 21 and June 21, as per Western

astrology. (This was initially detected by Marco Pasi, the first person with whom Colombo had shared the watercolor image).

Ladies of the Liberal Club, painted by Aleister Crowley in May/June, 1918, New York City. The caption with the painting is (penned with Crowley's typical wit) 'Mrs. Tyler says it is a wonderful portrait of Mrs. White, and Mrs. White says it is a wonderful portrait of Mrs. Tyler.' (With thanks to LAShTAL.com poster 'OKontrair').

There was initially some confusion about the dating of the painting. Despite the May/June 1918 dating, I could not find any mention of Crowley painting at that time, from either his Confessions or any of his previous biographers. In Confessions he states that he began his ‘first attempt at painting in oil’ sometime after September 9th, 1918.2 This was shortly after his return from his ‘magical retirement’ on the Hudson, during which he claimed to have accessed memories of a number of previous lifetimes. This mystery appears to be solved by the question of the medium Crowley worked in. John Robert Colombo had confirmed that the painting in question was in fact a watercolor. Apparently Crowley initially worked in watercolor, and after September 1918, began to experiment with oils.

It turns out that the painting was part of the ‘New York Collection’, a group of works by Crowley that arose out of his years in New York City. According to Breeze, Crowley had exhibited the painting in question—which had been officially identified as being ‘Two Ladies of the Liberal Club’—at said Liberal Club, which was located in Greenwich Village in Manhattan, on a six-block avenue known as MacDougal St. This street has quite a history, having had residents as notable as Bob Dylan, Jackson Pollock, and Eleanor Roosevelt, and housing pubs and cafes that had been frequented by the likes of Ezra Pound, e.e. cummings, Jack Kerouac, Ernest Hemingway, Marlon Brando, and Henry Miller. Bette Davis and Jimi Hendrix were said to have launched their careers at venues there and Anais Nin self-published her first three books at a print shop on the same street.

MacDougal St., Greenwich Village

The Liberal Club itself—a ‘meeting place for those interested in new ideas’—had been founded in 1913, and as with many such intellectual ventures of the time, was something of an outgrowth of the 19th century fin de siecle (‘end of the century’) European cultural ambience, during which great change was anticipated while at the same time cynicism with existing worldviews was marked—something that is usually ripe ground for needed innovations in both intellectual and artistic realms. The MacDougal Street Liberal Club was frequented by such types as Jack London, Upton Sinclair, Max Eastman, and Theodore Dreiser. It was situated on top of a restaurant that was run by an anarchist couple, Polly Holladay and Hippolyte Havel, the latter renowned for his volatile manner and brash views on organization of any sort, much of which was allegedly vented as he served his customers.

Hippolyte Havel, the fiery anarchist himself, serving tables at his restaurant on MacDougal St., circa 1915. Crowley's paintings would be shown in the room directly above the restaurant, three years later.

William Breeze wrote to Colombo, and a couple of days later JR replied with a relatively detailed email outlining the provenance of the Crowley watercolor. (With JR’s permission, I repeat the salient details of the email here). It turns out that he’d first seen it in 1955, when he was around 19 years old, in the apartment of one Alexander Watt (1890-1961), an investment dealer who lived in Kitchener (Colombo's place of birth) a mid-sized town in southwest Ontario, about fifty miles west of Toronto. This town was heavily settled by Germans in the late 18th century and had originally been named Berlin. In 1916, owing to the anti-German sentiment of WWI, it was renamed Kitchener, after a British Field-Marshall. As a further point of interesting trivia, this was the same town William Lyon MacKenzie King was born in, Canada’s most notable prime minister—he led the country for most of the ‘heroic’ years between 1921 and 1948—and was famous for his deep interest in the occult, which included his usage of trance-mediums to receive ‘messages’ from ‘spirit guides’, one of whom he claimed was Leonardo da Vinci, to provide essential political and spiritual guidance.

William Lyon MacKenzie King (1874-1950), Crowley's contemporary and Canada's 'occult' Prime Minister

Alexander Watt was English by birth, and held a seat on the Toronto stock exchange. Colombo described him as a ‘local character’, and added that Watt owned a large personal library of occult books, something unusual for that place and time. There was also mention of ‘manuscript material’ and correspondence with Karl Germer (1885-1962, outer head of Ordo Templi Orientis from 1947-62) and Manly Palmer Hall (1901-1990), the Canadian esotericist whose massive encyclopedic work The Secret Teachings of All Ages is practically required reading for any serious student of the history of the occult.

Karl Germer and Manly Palmer Hall

JR mentioned that at that time in the

mid-1950s he’d been part of a ‘small, ad-hoc’ group of occult students, to

which Watt ‘spoke occasionally about Crowleyanity, obliquely about

Rosicrucianism, openly about Anthroposophy, and knowingly about Theosophy.’

Some information on him is available via various archived online sources. Watt was a Rosicrucian (among other things),

and had an interest in linking the exactly three centuries between the 1604

appearance of the Rosicrucian Manifesto, and the scribing of The Book of the Law in 1904; he knew

Crowley, at least via correspondence, as well as Karl Germer. Watt apparently

attempted to produce a series of editions of Crowley’s Holy Books, but the

production quality was not good.(3) Watt was also an OTO initiate (his initiate name GADA.'. appeared in many of his books). Crowley had given him twenty copies of a special edition of OLLA (1945), his very last published work, as a token of appreciation for Watt's efforts. (See Queen's University note below).

There is a fairly extensive mention of Alexander

Watt in numerous archived editions of The

Canadian Theosophist. For example, in the September 1935 edition (the year

before John Robert Colombo was born), he is listed as President of the

Kitchener Lodge. He is also listed as president of the same lodge as recent as

the 1958 edition, so apparently he held this position for some time, though in

certain years he alternated roles with the lodge’s secretary.4

It’s been my impression over the years that Crowley draws roughly two general kinds of seekers to his ‘flame’. I would categorize these as those struggling with anti-authoritarianism in all its guises—which Freud likely correctly identified as primarily an unconscious battle with the ‘Father’—and what I would call ‘intelligent rebels’. The first is drawn to Crowley because he seems to represent a big ‘screw you’ to authorities of the most powerful kind, beginning with the legacy of Judeo-Christian-Islamic Abrahamic faiths. Such an anti-authoritarianism is both perverse and averse in the most striking ways, which of course is part of Crowley’s basic legend. Needless to say, however, many using him as such an outlet for their own repressed hostilities will not be mature in esoteric practice, until such unresolved authority issues are worked out to some degree in conventional life (necessary if one ever seeks real personal empowerment for oneself—it’s hard to be a successful leader if you’ve spent your life resenting other successful leaders).

The second type of seeker—the ‘intelligent rebel’—is reasonably mature (physical age notwithstanding), and has the intelligence to see past superficial appearances and appreciate genuine intelligence when it is there. Crowley himself was a walking opportunity for a seeker to be ‘tested’ in that regard, because his loudly crude ‘flaws’ made it easy to become distracted by these ‘flaws’ and assume that there was nothing beyond them, which, of course, included his absurdly dramatized reputation, as first shouted about by Horatio Bottomley and other ‘barons’ of the yellow press. (An excellent parallel for this matter was Osho’s Rolls Royces—it was always interesting to watch people react to these cars, as their various issues came bubbling up, be they unresolved greed, jealousy, pious judgmentalism, and so forth—to the point that it became absolutely impossible for them to notice anything beyond the cars. Gurdjieff suffered similar skewed perceptions, mostly in relation to his drinking, obscene language, and occasional flirtatiousness with female students).

The following letter written by Watt, and published in the July/August 1956 edition of The Canadian Theosophist, shows his sharpness and clear membership in the ‘2nd group’ just specified:

The Editor, The Canadian Theosophist,

Sir:

May we, the least significant of the Canadian Lodges, be one of the first to congratulate those responsible for adorning the latest jewel in the Theosophical Crown—the Phoenix Lodge in Hamilton. We wish them Bon Voyage and pleasant sailing.

While we regret to see a division in a long established Lodge like the Hamilton Lodge with all its cultural associations, its record for tolerance, and the happy memories of its guidance by our beloved and departed Brother Albert E.S. Smythe from his exalted exedra, we must perhaps realize that the Ambitious City is growing up and that the recent dichotomy is due to the fact that the newcomers desire a new type of theosophy - such is the Zeitgeist!—and hence a new Lodge. This rare bird, however, must not be in any way understood as arising from the ashes, or even embers, of the Hamilton Lodge, because we know that body to be a brilliant and ever-burning lamp to lighten the gentiles in that city!

We read with interest the ‘notes and comments’ of our General Secretary in the May-June issue of The Canadian Theosophist, especially where he says that some members of the old Hamilton Lodge have found ‘the great Divide between those who live on the Mountains and those who live on the Plains’ is too strenuous in a physical way. He omitted to mention the Valleys, perhaps as it is there the pilgrims view the radiant Body of Isis as through a mist! Those on the Mountains, however, with eagle sight, should not find it necessary to even consider the formation of a second Lodge in any one city. And this brings us to what we consider a very important matter.

It is of course understood and goes without saying, that those ‘in high places’ who dispense Charters to newly formed Lodges, do so after applying every acid test to those making the application, especially as to the ‘brand’ of theosophy they have in mind propagating. The older Lodges and the inactive ones, affiliated with the Canadian Section, are all voluntarily pledged to uphold Blavatskyan Theosophy, and in these times, it should be a matter of responsibility to those issuing new Charters, to see that the present day characterizations of theosophy do not creep into our august society.

We understand there has always been an esoteric section in the Theosophical Society and always will be but we deplore the ‘casting of pearls’ and the open exposition of pseudo occultism to all and sundry newcomers, who find themselves attracted to the flame of psychism.

These remarks are occasioned by reading the report of the inaugural meeting of the Phoenix Lodge in which its Secretary, Stella Ballard, states:

‘Regular meetings have been held on Wednesday evenings consisting of a series of helpful and aspiring meditations…’, and ‘Mrs. Gladys Miller has been conducting breathing exercises for daily use, together with a method of utilizing the cosmic rays…’

We hope we are not doing an injustice to this new group and do not wish to say or suggest anything that might retard their full flowering, or perhaps we should say—full feathering, and it may be that the report referred to a private and closed meeting of the Lodge—we do not know. We sincerely hope, however, that publicly and in open meeting, subjects of this nature are not put forth as ‘theosophy’, as we who hold our theosophy dear, would then find it necessary to dissociate ourselves from the new thought. The first object of the Society is a full meal for most of us in this incarnation. The second is a refection for epicureans, while the third is oft-times nothing more than a nauseous mess for gluttons.

Let all good theosophists in Canada sit down together at what will be our Last Supper for awhile, and arise refreshed and sustained by a well-balanced meal that will not cause the least delicate to complain of indigestion.

Yours very sincerely,

Kitchener Lodge,

Alexander Watt Pres.5

Watt was sixty-six when he wrote that letter, evidence that he had certainly

not become apathetic in his twilight years. In particular is to be noted his courage and alertness in 'calling out' the tendency of many esoteric groups to drift into a kind of mushy emotionalism that breeds excessive interest in psychic matters. The letter upset some people

connected to the fledgling Phoenix lodge, which fired back in predictable

fashion. Watt’s reply, in the January-February 1957 edition (selective parts of

interest shown below), sheds light on his ‘extracurricular’ esoteric interests,

and mentions the ‘ad-hoc’ occult circle that he led, and which John Robert

Colombo had occasionally attended :

The Editor, Dear Sir:

...the writer has been deeply interested in the esoteric side of Theosophy for many years and while he is the present President of the local Lodge, he has always kept Esotericism separate from the Lodge and has conducted a class in his own home along esoteric lines, but has never called it a Theosophical study group or any other class inferring as much. The Kitchener Lodge Chartered in 1935 has carried on continuously since that time. During that time there has been a period of Pralaya and a balancing Manvantara. If on the surface the Lodge has not been active and numerically strong, that does not suggest that Theosophy has not been active in the district. Some Lodges can be numerically strong and Theosophically weak. Oft-times an insidious and iconoclastic worm will be found boring at the heart of the most perfect apple.

As I have said earlier, I wish nothing but the best for the new Phoenix Lodge and its Members, many of whom I count my very good friends, but their success will be measured in my humble opinion by the quality of the Theosophy they present from their platform...

Yours fraternally,

Alexander Watt.6

The following book review (from the 1958 edition of The Canadian Theosophist) is of a short booklet of Watt’s writings.

The booklet makes reference to Crowley and a particular Tarot card:

BOOK REVIEW

Blessed Be He: A Tribute to Alexander Watt, a selection from his writings (The Hawkshead Press, Box 333, Kitchener, Ontario, Canada), 24 pages; edition limited to 126 copies which are signed and numbered by the author for his private distribution.

The strange title of this booklet, Blessed Be He, is taken from an ancient Hebrew legend which describes the creation of the universe. It is not as easy, however, to explain the contents of this booklet, for the ten sections which compose it are varied, being selections from the lectures, articles and poetry of Alexander Watt, a Canadian Theosophist and lecturer of no mean repute.

Outwardly Blessed Be He is a handsome piece of typography; it is printed in two colors on a textured stock which resembles parchment. Inwardly Blessed Be He is a sustained rhapsody celebrating the sensuous aspects of the spiritual life. Since the tone of the writing is oracular arid poetical, the booklet is couched in symbolic references. These reflect the author’s wide range of studies which include the Qabala, Rosicrucianism, Theosophy, Anthroposophy, Crowleyism, Christianity and the Tarot, although it will be noted that these diverse influences have been integrated into a greater whole.

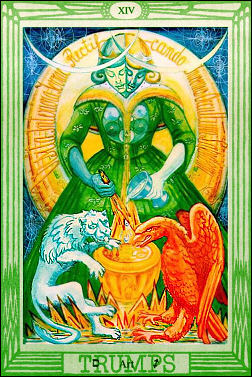

While it is difficult to analyze Blessed Be He, since the booklet abounds in suggestive paradoxes, perhaps its most beautiful sections are those two which describe Crowley’s ‘star-sponge’ and the author’s meditation on the fourteenth Tarot card. In the former the ecstasy associated with the soul’s merging with the feminine pole of manifestation is described, and in the latter the author sets forth a parable which is the archetype of the soul’s adventure along the mystical path.

Aside from a few obvious misprints, Blessed Be He is a beautiful presentation, in capsule form, of a complete philosophy of life which holds that the highest life is the spiritual life. It is unfortunate that Blessed Be He will be available to only so few, since its oracular tone necessitates frequent re-readings, and, since it would be appreciated by many more than the author's immediate acquaintances.

—‘Ruta’7

Concerning the ‘Star-Sponge’, an insightful essay by Bill Heidrick on the matter can be read here.

Tarot trump #14 is typically called ‘Temperance’; in Crowley’s Thoth Tarot deck, it is ‘Art’ -- doubtless an appropriate Trump card for an article about his painting efforts.

Crowley’s writings on this card, from The Book of Thoth, can be read here.

Alas, the Canadian Theosophical Society apparently did not hold Crowley in much regard, as the following breathless article from the September, 1935 edition, suggests:

FRAUDULENT IMPERATOR OF AMORC

Dr. R. Swinburne Clymer has just issued a third extensive exposition of the false and fraudulent methods of the Imperator of the AMORC, Mr. Spencer Lewis, and it should resolve the doubts of the many correspondents who have been writing to us and trying to convince us that we are unjust and wrong to denounce the methods of this gentleman in deluding the members of his organization as he does. We have no quarrel with these members nor with any others who are gullible enough to be deceived and misled by false teaching and baseless pretenses, nor can we boast of the Theosophical Movement in this respect with the example of Mr. Leadbeater before us.

The AMORC has made such ridiculous claims and these have been so widely accepted that it is only fair to the public and those who have been deceived, to let them know how fully these pretenses and falsifications have been exposed. The present book of 128 pages issued by The Rosicrucian Foundation, Quakertown, Pennsylvania, presents 34 fac simile documents proving that the alleged original Rosicrucian teachings issued by Lewis, the Imperator, are pilfered from well-known works of such writers as Dr. Franz Hartmann, Von Eckhartshausen, Dr. Richard Maurice Bucke, William Walker Atkinson, Johann Valentin Andreae, and others, particularly the notorious Aleister Crowley from whom he has derived his chief authority, and his title and such charter as he purports to possess being, as Dr. Clymer points out, 'the Most Illustrious Master of Black Magic and a Most Adept Black Magician,' whom, notwithstanding Lewis, is said 'to acknowledge to be his Secret Chief'.

This book and its companion volumes, 'A Challenge and the Answer,' and 'Randolph Foundation the Authentic Body has Exclusive Rights to use of Rosicrucian Names,' completely shatter the deceitful and misleading claims of Spencer Lewis. In an appendix the testimony of A. Leon Batchelor, a former treasurer of the AMORC, is given in which he states that the whole object of AMORC is to supply funds to the Lewis family, who built their homes with the funds and paid their household expenses out of the property, valued at half a million, with $400,000 cash in the bank and an annual income of about $350,000. Mr. Batchelor says 'it is a sad reflection on AMORC that about 400 members drop out each month; that about an equal number each month are caught in the meshes of Lewis's untruthful and unethical advertising, soon too drop by the wayside, and their places to be taken by new victims.' It is a sad reflection also on the gullibility of the public that they are willing to pay heavily for the bogus teachings of AMORC, and yet neglect, in Canada at any rate, to investigate the Theosophy which we offer free.

The people appear to love to be fooled, and perhaps it is necessary that

they should have such experience. Yet they do not seem able to learn to

discriminate. Dr. Clymer deserves much credit for taking such pains to lay the

evidences regarding this 'most successful deceiver, a vile impostor, a

clever charlatan and a crafty sorcerer,' as he terms him, before the

world. These books are supplied free to those interested. We observe that the

cost of postage is 21 cents.8

Alexander Watt died in a car accident in early 1961, aged 70:

IN MEMORIAM

Death came with tragic suddenness to Alexander Watt of Kitchener Lodge in a motor accident on January 23, 1961. Mrs. Watt was severely injured.

Mr. Watt formed the Kitchener Lodge shortly after he moved from London, Ont. to Kitchener and from that time he was the main support of the Lodge. He was an earnest student of Theosophy and the Kabala and his lectures on these subjects were looked forward to by members of Toronto and Hamilton Lodges as Mr. Watt always presented his material in dynamic and original manner. The last farewells to this active worker were said at a Theosophical funeral service held on Thursday, January 26 at the Toronto Crematorium.

Our deep sympathy is extended to Mrs. Watt and to Hugh and Alexander and to members of their families.9

Watt’s library of rare books, along with his various letters of correspondence with Crowley, Germer, Hall, and others, as well as his Crowley watercolor, was inherited by his son Hugh, an assembler of electronics products. Hugh held on to the material for a few decades, and then decided, in 1989, to donate the rare books and other material to the library of Queens University of Kingston (which is halfway between Toronto and Montreal). The university accepted the books, but according to Colombo the chief librarian ‘took a pass’ on the cache of correspondence (which included ‘four heavy cartons of unpublished material’ as well as Crowley’s painting), ‘alluding to the ravings of a madman’. Hugh Watt, now in his own senior years and wishing to unburden himself of the cartons, then passed them on to John Robert Colombo reasoning that he was the ‘senior surviving member’ of Alexander Watt’s original ad-hoc group of occult students. JR has quietly owned the material since then. And so the passage of the painting was from Crowley, to Karl Germer, to Alexander Watt, to Hugh Watt, to the Queen's University librarian to immediately back to Hugh Watt, to John Robert Colombo (since 1989).

Further details about Alexander Watt and his library can be read in the Queen's University Special Collections page here.

It may comfortably be said that the power of

all art resides in the personal mind and energy of the craftsman. A work of art

can no more be separated from the one who fashioned it than a beam of light can

be separated from its light source. Crowley

himself would have had no cause to disagree with that. In 1908, when he was

wandering through Spain

with Victor Neuburg, he made the following observations:

In the galleries of the Prado there is no occasion to trouble about such matters. The place fills one with uttermost peace; one goes there to worship Velasquez and Goya, not to argue. Perhaps I was still too ingenuous to appreciate Goya to the full. On the other hand, there may be something in my impression that he is badly represented at Madrid. Much of his work struck me as the mechanical masterpieces of the clever court painter. Possibly, moreover, there was no room for him in my spirit, seduced, as it was, by the vivid variety of Velasquez. ‘Las Meninas’ is worshipped in a room consecrated solely to itself, and I spent more of my mornings in that room and let it soak in. I decided then, and might concur still had I not learnt the absurdity of trying to ascribe an order to things which are each unique and absolute, that ‘Las Meninas’ is the greatest picture in the world.

Las Meninas by Diego Velasquez (1599-1660)

It certainly taught me to know the one thing that I care to learn about painting: that the subject of a picture is merely an excuse for arranging forms and colours in such a way as to express the inmost self of the artist.10

Initially Crowley did not have a great affinity with visual art; as with most intellectuals, his natural pull was toward literature. He wrote:As a critic of art I have curious qualifications. My early life left me ignorant of the existence of anything of the sort beyond Landseer's 'Dignity and Impudence'. I suppose I ought to have deduced the existence of art from this alone had I been an ideal logician. Such horrors imply their opposites. However, even in my emancipation I never discovered art as I did literature. It never occurred to me that there might be a plastic language as well as a spoken and written one. I had no conception that ideas could be conveyed through this medium. To me, as to the multitude, art meant nothing more than literature.11

Gerald Kelly, brother of Crowley’s first wife, Rose, and a painter himself, was to be a marked influence on Crowley’s eventual interest in visual art:

The first picture that awakened me was Manet’s wonder ‘Olympe’, enthusiastically demonstrated by Gerald Kelly to be the greatest picture ever painted. I could see nothing but bad drawing and bad taste; and yet something told me that I was making a mistake.12

Manet's Olympia, painted in 1863.

When I reached Rodin shortly afterwards I understood him at once, because the sculpture and architecture of the East had prepared me. I knew that they were the expression of certain religious enthusiasms, and it was easy for me to make the connection and say, 'Rodin's sculpture gives the impression of elemental energy.' Yet this was subconscious. In my poems I have treated Rodin from a purely literary standpoint.

As time passed my interest in the arts increased. I was still careful to avoid contemporary literature lest it should influence my thought or style. But I saw no harm in making friends with painters and learning to see the world through their eyes. Having already seen it through my own in the course of my wanderings, I was the better able to observe clearly and judge impartially. Perhaps this circumstance itself had biased me. It is at least the case that I have no use for artists who have lost touch with tradition and see nature second hand. I think I have kept my head pretty square on my shoulders in the turmoil of the recent revolutions. I find myself able to distinguish between the artist whose eccentricities and heresies interpret his individual peculiarities and the self-advertising quack who tries to be original by outdoing the most outrageous heresiarch of the moment. 13

Anyone who considers the entirety of Crowley’s life will be struck by a few things, not least of which will be his energy-level. The man had very high personal energy, an intensity that reflects pointedly in his paintings. It is sometimes said that what marks an ‘initiate’ of the inner schools is a certain ‘personal frequency’ or intensity that, if properly parlayed, allows them to concentrate two or three ‘lifetimes’ into one. The expression ‘larger than life’ may seem odd upon inspection (how can anything be larger than that which contains it?) and yet it is an apt metaphor for one whose intensity translates into a type of personality that attracts many and varied experiences. Such a type is often involved in dramatic events, because others, like moths to a flame, seek to manufacture such events and thereby work out various personal unfinished business via the locus of the ‘larger than life’ personality. (Freud identified this process in a therapeutic context as ‘transference’, whereby a patient will seek to work out all sorts of issues via the interplay of their relationship with a therapist, but it also takes place in the field of interaction between highly charismatic personalities and those around them).

Of course, not all ‘initiates’ are occult masters or Eastern gurus or even particularly wise. Some are scientists, some politicians, some religious leaders, and some artists, writers, poets, leaders or initiators (i.e., creators) of many stripes. A more advanced initiate may be said to be one who has what Gurdjieff called a planetary aim (that is, is fundamentally concerned with the evolution of the human race), and as such, is less self-absorbed.

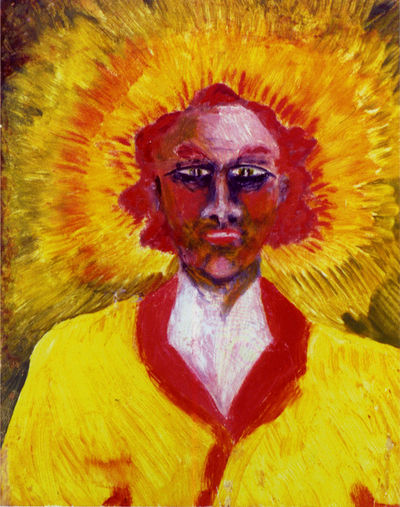

It could be speculated that Rembrandt and Van Gogh, though far superior

artists in contrast to an art-dabbler like Crowley, were immature initiates, if only

because of their near obsession with self-portraits (although that said, Van Gogh's early death nullified any opportunity to blossom further in vision and wisdom). But the fantastic energy is there, as it was with others like Leonardo and Michelangelo, a single-mindedness that is basic to the seeker who penetrates the mysteries of existence.

Self portraits of Rembrandt, Van Gogh, and Crowley

All maturation involves the movement from fascination with self, to interest

in the Other (initially manipulative, to an interest ultimately free of agenda), to interest in the non-dual (beyond I

and Thou). I think Crowley’s art, though perhaps in places as visually nauseating

as a Hieronymus Bosch or even a Picasso, shows some of those countering

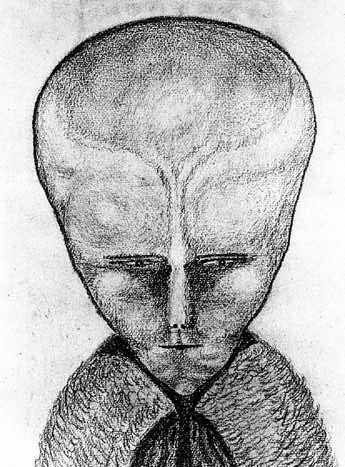

influences that perhaps reflect his own maturation via his art -- from fascination with self (his highly charged self-portraits), with

the Other (his many portraits of others), to his ultimate interest in transcendence of both

(perhaps embodied in his renowned figure called LAM, shown below, and its implied potential

for transcendent consciousness).

The sketch of LAM was an outgrowth of Crowley's 'Amalantrah Working', drug and sex magick-influenced visionary work he'd undertaken with his lover Roddie Minor in early 1918, just a few months before he painted the 'Ladies of the Liberal Club'. Given LAM's association with non-terrestrial intelligence, this perhaps brings us full circle to John Robert Colombo's UFO book I alluded to at the beginning of this essay. But that's another story for another time.

Notes

1. John Robert Colombo’s homepage can be

accessed here. His Wikipedia page can be viewed

here.

2. The Confessions of Aleister Crowley: An Autohagiography, edited by John Symonds and Kenneth Grant (London: Penguin Books, 1979), p. 791.

3. See http://www.weiserantiquarian.com/cgi-bin/wab455/30860.html

4. These are available online via the Theosophical archives, for eg., http://theosophy.katinkahesselink.net/canadian/Vol-37-1-Theosophist.htm

5. http://theosophy.katinkahesselink.net/canadian/Vol-37-3-Theosophist.htm

6. http://theosophy.katinkahesselink.net/canadian/Vol-37-6-Theosophist.htm

7. http://theosophy.katinkahesselink.net/canadian/Vol-39-5-Theosophist.htm

8. http://theosophy.katinkahesselink.net/canadian/Vol-16-7-C-Theosophist.htm

9. http://theosophy.katinkahesselink.net/canadian/Vol-42-1-Theosophist.htm

10. Confessions, p. 586

11. Ibid, p. 585.

12. Ibid, p. 585.

13. Ibid, p. 585. A ‘heresiarch’ is the founder of a heretical faith, movement or doctrine.

_____________________________

Crowley on Canada

I've long been greatly amused by Crowley's brief comments on Canada in his Confessions. Canadians (in general) have the trait of a self-deprecating sense of humour, owing doubtless in no small part to being in the immediate shadow of the jazziest nation on Earth (although China fast creeps up). Accordingly we Canadians have developed a healthy ability for self-parody. Crowley's remarks, delivered with his patented forthright take-no-prisoners style, only enhances the humour.

He was one of the great

travelers of his era, among his fellow mystics rivaling Blavatsky and Gurdjieff for sheer quantity of

mileage logged in his wanderings. Commercial international airline travel did

not begin until the 1920s, and in those early days was sporadic in availability.

Prior to that (and for most people, well into the 1950s) the standard means of long distance travel was by boat and train.

By Crowley’s mid-20s he’d already sailed across both the Atlantic and the

Pacific, and had traveled the Americas and parts of Asia. In late April of 1906,

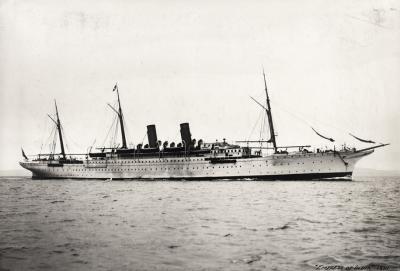

aged thirty and already a seasoned traveler, he boarded the Empress of India and sailed from Japan

to Vancouver, B.C. He then took a train across the vast expanse from B.C. to Niagara Falls.

The words below are extracted from his Confessions.

I sailed on April 21st by The Empress of India, took a flying glance at Japan and put out into the Pacific.

A savage sea without a sail,

...

Grey gulphs and green aglittering.

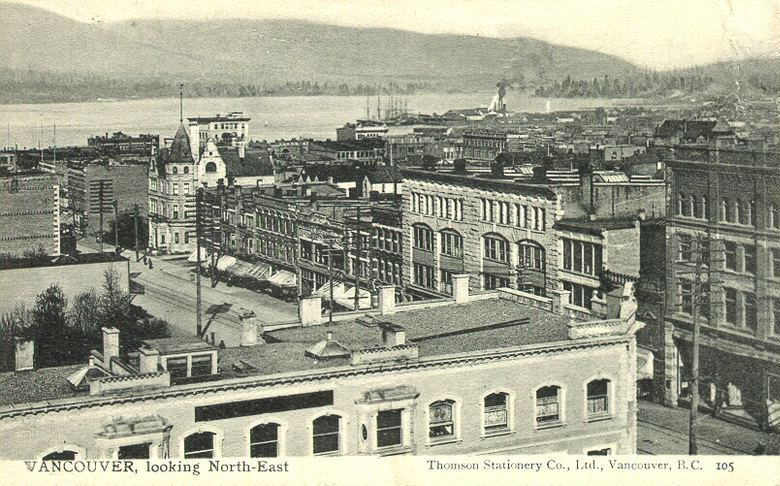

We never sighted the slightest suggestion of life all the way to Vancouver, twelve days of chilly boredom, though there was a certain impressiveness in the very dreariness and desolation. There was a hint of the curious horror that emptiness always evokes, whether it is a space of starless night or a bleak and barren waste of land. The one exception is the Sahara Desert where, for some reason that I cannot name, the suggestion is not in the least of vacancy and barrenness, but rather of some subtle and secret spring of life. Vancouver presents no interest to the casual visitor. It is severely Scotch. Its beauties lie in its surroundings.

Exciting downtown Vancouver in 1906.

I was very disappointed with the Rockies, of which I had heard such eloquent

encomiums. They are singularly shapeless; and their proportions are unpleasing.

There is too much colourless and brutal base; too little snowy shapely summit.

As for the ghastly monotony of the wilderness beyond them, through Calgary

and Winnipeg right on to Toronto—words fortunately fail.

The manners of the people are crude and offensive. They seem to resent the

existence of civilized men; and show it by gratuitous insolence, which they

mistake for a mark of manly independence.

The whole country and its people are somehow cold and ill-favoured. The character of the mountains struck me as significant. Contrast them with the Alps where every peak is ringed by smug hamlets, hearty and hospitable, and every available approach is either a flowery meadow, a pasture pregnant with peaceful flocks and herds, or a centre of cultivation. In the Rockies, barren and treeless plains are suddenly blocked by ugly walls of rock. Nothing less inviting can be imagined. Contrast them again with the Himalayas. There we find no green Alps, no clustering cottages; but their stupendous sublimity takes the mind away from any expectation or desire of thoughts connected with humanity.

The Rockies have no majesty; they do not elevate the mind to contemplation of Almighty God any more than they warm the heart by seeming sentinels to watch over the habitations of one's fellow men.

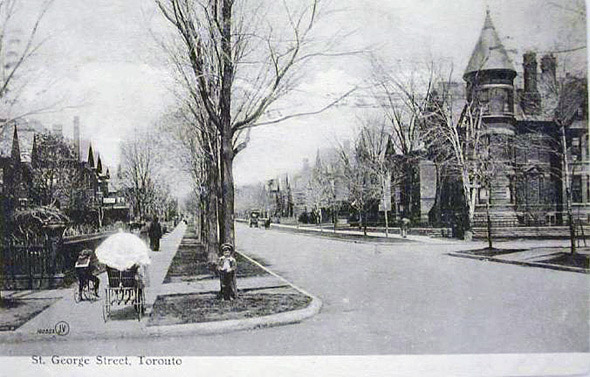

Toronto as a city carries out the idea of Canada as a country. It is a calculated crime both against the aspirations of the soul and the affections of the heart.

Thrilling Toronto, 1906.

I had been fed vilely on the train. I thought I would treat myself to a really first-class dinner. But all I could get was high-tea—they had never heard the name of wine! Of all the loveless, lifeless lands that writhe beneath the wrath of God, commend me to Canada! (I understand that the eastern cities, having known French culture, are comparatively habitable. Not having been there I cannot say.)

I hustled on to Buffalo to see Niagara. Here I first struck the American newspaper reporter in full bloom, in his native haunts. Before I had been half an hour in my Hotel I was tackled by a half a dozen enthusiastic scribes. I naturally supposed that they had somehow heard of my Himalayan or Chinese adventures, and talked accordingly. It gradually dawned on me that somehow I was failing to fill the bill; and I presently discovered that they had mistaken me for some English lieutenant who was supposed to have crossed from Canada and from whom they wanted information about some local foolishness.

I took a pretty good look at Niagara. It is absurd to shriek at the desecration cause by building a few houses in the vicinity. It seemed to me that they helped rather than hindered one's appreciation. They supplied a standard of comparison. All that has been said of the falls is, as the sayers admit, ridiculously below the reality. In their way they challenge comparison with the mountains of Asia themselves. They have the same air of being out of all proportion with the observer. They belong to a different scale; and they impress one with the same idea of utter indifference by nature. They fascinate, as all things vast beyond computation invariably do. I felt that if I lived with them for even a short time they would completely obsess me and possibly lure me to end my life with their eternity. I felt the same about the mountains of India, the expanse of China, the solitude of the Sahara. I feel as if the better part of me belonged to them, as if my dearest destiny would be to live and die with them.

The Niagara Falls -- the Canadian side

Crowley's remarks on Canada taken from The Confessions of Aleister Crowley, Penguin Books, 1979, pp. 501-502.