The Magus of Montreal

I have known many strange and compelling characters on my long journey through the worlds of spirituality, personal growth, the esoteric and the occult. One of my earlier influences was a man I will call Willard (not his real name). He was a complex individual. He was in my life for a couple of years in the early 1980s, before mysteriously disappearing one day. The following is reconstructed from old diaries and vivid memory of his quirky nature.

Chapter 1

Montreal, 1982.

‘She is the whore of Babalon’, Willard casually remarked

later that evening, after she’d gone, and he and I sat smoking and drinking

more wine under a dimly lit red lamp. I looked at him quizzically. We had just

finished a strange afternoon sharing company with a Native Indian woman who

claimed to be some sort of witch-doctor. The whole thing had evolved into a

rather bizarre and unexpected menage a trois.

‘You mean in the sense that Crowley meant it?’

I wasn’t listening closely to his occult mumbo-jumbo. I’d gotten laid, and I cared more about eating some cheap food from the nearby depanneur at the moment.

‘There’s something you can do to accelerate the process of your opening’ he added, his brow furrowing. Whenever he pulled that face he looked like the war vet he was, about to tell me one of his harrowing stories from his days in the trenches in Vietnam.

‘What?’ I asked in a half-hearted fashion.

‘Imagine Jesus masturbating.’

Now he’d caught my attention. That just seemed weirdly theatrical. Why Jesus? Why not Vlad the Impaler, or better yet, Karen Black?

‘That’s fucking strange,’ I muttered. He laughed.

‘That’s precisely why you should do it. Because you think it’s fucking strange.’

I knew that Willard usually had an agenda when he seemed to present a teaching. I pressed him for it.

He lit up a cigarette. In the dim glow of the old lamp, with

his glass of wine and now shrouded in smoke, he looked vaguely like a grizzled

lizard.

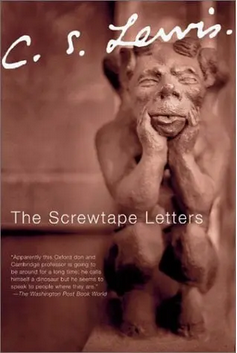

‘Are you familiar with The Screwtape Letters?’

‘The Screw what?’

‘The Screwtape Letters. It was a famous short novel written by C.S. Lewis in the mid-20th century.’

I grunted. The name at least was familiar. ‘You mean the guy who wrote The Chronicles of Narnia?’

‘Well at least you are not completely unlettered. Yeah, that guy.’

He took a long drag and blew his smoke toward me. It was an

annoying habit he had whenever he was about to launch into some monologue.

‘The Screwtape Letters is about a demon named Screwtape, who is providing instructions to his nephew Wormwood on how to successfully manipulate some hapless human, with the objective to turn the human away from God and toward the Lord of the Underworld.’

‘Wormwood’ I interrupted. ‘Isn’t that a name from the Book of Revelation?’

He nodded quickly, looking vaguely annoyed that I had interfered with his flow.

‘Yes. It’s identified as a particular star in Revelation. But more on that later. For now, what you need to know is that Wormwood is a lesser demon being instructed by his superior, who also is his Uncle Screwtape.’

Willard smirked that weird smirk, whenever he seemed proud of his obvious covert implication. But I didn’t see him as my uncle, even if he fancied that. He cleared his throat and continued.

‘In the novel, Wormwood is attempting to sway a certain man—identified only by the designation ‘the patient’—toward the dark side, away from the ‘Heavenly Father’, who is referred to by Screwtape only as The Enemy.’

‘Clever,’ I replied. ‘But wasn’t Lewis a Christian?’

‘He was, essentially, but who cares? Quality is quality. The man could write.’

This was an important point with which I could only agree.

Even at that unripe age I sensed the wisdom in that non-partisan view.

‘Screwtape tells his nephew Wormwood some important ideas relating to sexuality and commitment,’ Willard continued. ‘He stresses the idea that ‘the Enemy’ (God) has instilled in people the notion that they must either abstain from sex or be completely monogamous.’

He paused for dramatic effect, to let his words sink in. I began to detect where he was going.

‘Of course Screwtape needs to get across an important point to his protégé, and it is this: in the lower regions, the hell-realms, everyone is isolated and disconnected from everyone else. The cult of the individual is paramount. And Lewis, by having his Screwtape present this notion to Wormwood, is arguing, in a backhanded fashion, that Christianity really has it right, and that people should not be sexual unless they are married and settled. And then through that path, they can know true harmony via the faceless blending of their personalities.’

He cocked his head at me and looked serious and even a bit fierce. His eyes glinted in the dim light and he butted out his cigarette.

‘Only problem is, on this point Lewis was full of shit. His book is regarded as a classic, but it is just clever Christian apologetics.’

I stood up. I was getting restless and needed to take a piss. Willard went into the kitchen to make himself a ham sandwich. I joined him there.

‘The main point to get is that you cannot really come close to another person—in any authentic way—unless you have experienced your lonesomeness first, and especially, the full exploration of your desires. Effectively, you do need to go to Hell. At least by Lewis’s standards!’ And with that, he laughed. I chose the moment to protest.

‘But all this left-hand crap, isn’t it just for restless young people seeking a justification to rebel?’

He snorted and attacked his ham sandwich. ‘That’s precisely the point. Are you not a restless young person seeking justification to rebel?’

I began to impulsively answer, but caught myself. He had me there. I was attacking a position that I myself was largely standing on.

‘Fuck this shit’ Willard blurted impulsively, as he was wont to do, while he threw out what was left of his sandwich. ‘Let’s go for a walk’.

Outside, the leaves were gold and red and swirling on the ground. It was a chilly October evening. We were walking through a local park. As a man walking a dog approached, Willard murmured something to me. I didn’t hear him.

“What?” I had to speak loudly, as a strong wind had appeared at that moment, muffling our voices.

“Watch this,” he said again. He then stood motionless and stared intently at the man’s dog. The dog immediately rolled over in some bird shit. The dog’s owner appeared annoyed, but soon lost interest. Back then, dog owners didn’t pick up shit, much less bird shit. My own dog once shit smack dab in the middle of Sherbrooke Street. Cars drove around us. I pulled my dog off the street, somewhat embarrassed. Dogs don’t get embarrassed; they just stop and shit wherever. Fuck what others think of me, I’m taking a dump right here.

I wasn’t impressed by Willard’s occult actions, if they were supposed to be that. “Watch what?” I asked. Willard glanced quickly at me with a dark glint in his eye, and then looked away. “Let’s go to Mario's” he said, referring to a local restaurant he and I occasionally visited. “You just had a sandwich,” I mumbled. He ignored me and headed off. I followed.

While in the restaurant, eating our meals, Willard suddenly put down his fork and started staring weirdly over my left shoulder. He was fixing his attention on something behind me. The restaurant was half-full so I wasn’t sure if he was staring at a person. I hoped that he wasn’t.

I glanced back over my left shoulder and saw that the recipient of his attention was an attractive women of perhaps 30. She was dining with a man whose back was faced our way. Only the woman could see us, and Willard was right in her line of sight.

I was uncomfortable with his staring, but this discomfort soon grew into outright alarm. In addition to staring at the woman with his piercing blue eyes, he began to lift his arms and make strange, conductor-like gesticulations with his hands. He was absolutely acting like a crazy person in an alley. But worse, he was focusing this craziness on one oblivious woman.

After a point I realized that there were mirrors on the restaurant walls, and that I was able to see the woman’s reflection in the mirrors without having to swivel my head back. I was soon being bizarrely entertained in a staid restaurant.

The woman was struggling to maintain her composure, her eyes growing larger, while she listened to her man who was droning on about something, completely oblivious to the fact that his woman was being targeted by a tremendously intense energy from a fellow diner sitting perhaps fifteen feet away.

No one else in the restaurant appeared to notice Willard’s theatrics. Even our server, who at one point ambled by to check on us. Willard continued his trance-like mannerisms while the server looked only at me, betraying not the slightest sign that he was uncomfortably ignoring Willard. It was rather as if Willard wasn’t there. (I dismissed the cynical thought that this server ignored Willard because if you’ve seen one crazy, you’ve seen them all, as this wasn’t a cheap eating hole).

After a while, following some strained murmuring between the couple, they got up and left. I imagine they paid for their dinner.

“What was that all about? Wasn’t it pretty fucking weird for you to be staring at that woman that way?”

Willard shrugged. I could see that he truly didn’t care. That marked him, in my mind, as either definitely disturbed, or definitely operating from some mysterious higher order of freedom. I couldn’t decide which one. I wanted it to be the latter, but suspected it was the former.

“I gave her a gift,” he said, somewhat to my surprise. “She was bored to tears, and wanting to be stimulated. I stimulated her.”

“How do you tell the difference between stimulating and invading?”

He narrowed his eyes at me, as if my probing was now becoming irritating. Or perhaps he was finally taking me seriously.

“In this world, the difference between the two depends on intent.”

“In this world?”

“Yes, in this world. In other worlds, intent is transparent, and so it manifests immediately.”

“But in this world, intent is not transparent,” I offered, somewhat mechanically.

“Correct. In this world, we have the ability to dissemble, to disguise our intent, or more commonly, to be unconscious of it.”

“You mean we can bullshit.”

“Bullshitting is but one avenue of expressing our extraordinary ability to deceive. We are lying spirits, by and large. This is why we are kin to demons.”

The discussion was becoming depressing. I began to think about dessert.

Suddenly Willard reached into his jacket pocket and tossed on the table a medallion of some sort, attached to a small chain. The medallion was bronze and inscribed with strange symbols, and what appeared to be a name spelled out. After a moment’s hesitation I picked it up and peered at it. It seemed to be a well-made occult trinket. Or perhaps it was an old artifact stolen from some ancient site. I couldn’t quite tell.

“Where did you get this?” I asked.

“It’s an heirloom,” Willard murmured, while sipping his drink. “Passed down from my 6th great-grandmother, who was one of the Salem women accused of witchcraft.”

I blinked at him. “Really?” I asked. He laughed. “Maybe. Or maybe I got it at the flea market.”

The look on his face made me doubt that. And besides, the thing really did look old and valuable, the more I examined it. “And what’s it supposed to do?”

He sneered. “It doesn’t do anything. It’s empty, as all these devices are. It’s a kind of mirror.”

“Then why bother with all the symbolism? Why not just get a mirror from Walmart?”

Willard had a bored expression on his face. Then he got up. He appeared to be distracted by something. Suddenly he wandered off toward the washroom.

The restaurant was beginning to thin out, as patrons faded off into the night. A few waiters ambled about, cleaning tables. My thoughts kept turning toward Willard’s shenanigans. His mental state concerned me. And yet he always seemed to pull it together in the end, in such a fashion that I would conclude that he must be teaching me something, like those crazy-wise teachers of lore. Although most of those guys turned out to be deviants of a different order.

My cloud of thought was disturbed by a figure looming over me. It was Willard, though strangely, he appeared from the opposite side of the restaurant from which he’d left the table. I looked around, momentarily disoriented.

“Let’s go,” he said, before dropping some cash on the table. He might be a crazy-wise teacher, but at least he was one who paid his bills. As we left, one of the servers stared after us, frowning, obviously relieved that the weirdos were departing.

Outside, wandering in the park, we sat down on a bench. Leaves swirled about. The low sunlight reflected golden on some trees. “Our hallmark moment,” I joshed.

Then he got into it.

“The medallion represents the symbol—or sigil—of an ancient demon. In this case, that of Agares.” He pronounced it “Ah-GAR-eez”.

I was all ears.

“These spirits are traditionally regarded as the offspring of the so-called fallen angels of biblical lore. You might be vaguely familiar with the story. At some indeterminable time in the ancient past, a group of angels, clustered around one dominant angel, rebelled against the existing divine order and were consequently ejected from the Plan. These spirits eventually mated with human females, producing the biblical giants of the old days. Then one day, after centuries of corruption and evil in human civilization caused by these half-angel, half-human, hybrid giants, the Big Guy upstairs decided that enough was enough and he opened the fucking floodgates, literally in this case.”

“Right. And the giants were all killed, along with everyone except Noah and his ark.”

“So the legend says,” he replied. “But the giants couldn’t be killed as they were offspring of immortal angels. And so they lost only their bodies. Their spirits remained.”

“In what form?” I asked, frowning. I suspected what his response might be. He paused for a moment. His expression was enigmatic, his eyes seeming to contain secrets. Or perhaps I was simply becoming mindful of my ignorance.

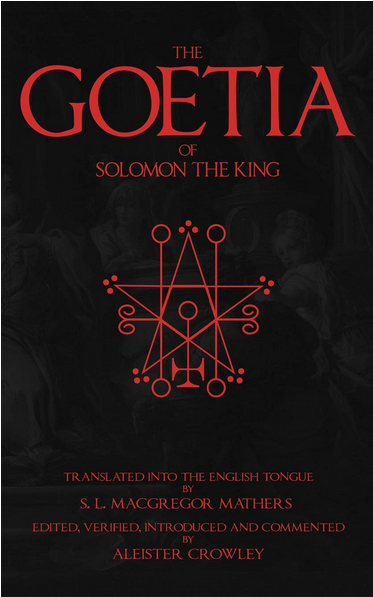

“They became the various spirits of the demonic grimoires, the catalogues of spirits found in various older cultures. One of the better known of these grimoires is called the Lemegeton, or the Goetia, with the latter word stemming from the old Greek ‘goetes’, meaning ‘sorcerer’”.

“And these stem from the early Christian period?”

“Not in the case of the Goetia. It appears to have been compiled only in the 1600s. But many of the spirits it lists have older roots, from Biblical times.”

“Which ones?”

“Well, take Bael, for example. He’s listed as #1 in the Goetia, but you can find over a 100 references to him in the Bible alone. But then there are other spirits who seem to have no history beyond the Lemegeton.”

“And all of them are just spirits, with no bodies?” This seemed vaguely comforting.

“All except one,” he replied, with an air of mystery. “Spirit #20 in the catalogue is a problem. He appears to be the only one that has the capacity to exist in physical form. Moreover, his sigil is the only one that remotely resembles a human figure. And even more oddly, his name is “Purson”.

I knitted my brows together. “Sounds awfully like ‘person’ I deduced.

Willard shot me a half-smile. He then stood up and stretched his muscles. At that moment, a man appeared from the far corner of the park, perhaps 200 feet away. He had a black Labrador-like looking dog by his side. The two of them just stood there, looking in our general direction. A wind gathered up at that moment, some leaves swirling strongly about.

Willard peered at the man. “It’s that lunatic,” he murmured. “Let’s go.”

I had no idea what he was referring to. But when I looked closer, I could see that the man had no arms. He was apparently a double-amputee. The leash-less dog followed him about like Agrippa’s mongrel.

As we energetically walked off in the opposite direction, I noted the quicker pace in Willard’s footsteps. “I wonder how that guy looks after a dog when he has no arms,” I thought out loud. Willard glanced at me with an amused look on his face. “Oh, he has arms,” he replied. “You just can’t see them.”

“How’s that?”

“He’s not a human,” Willard replied with what seemed equal parts legitimate gravitas, feigned seriousness, and a definitive exposing of his own mental illness.

I frowned at him. He laughed. I fancied I saw a mad twist in his face that reminded me of a Van Gogh self-portrait. “Come,” he suddenly said. “We are going to my place to conjure a spirit.”

The wind suddenly whipped up and a shadow passed over his

face. I felt ill at ease, and caught myself wondering just how this friendship

had ever formed. I'd only known him for a few months, but it all seemed weirdly orchestrated, fated, impossible to escape

from.

When we arrived at his place, the skies darkened and a thunder and lightning storm appeared, seemingly out of nowhere. Willard was arranging some things in his living room, when suddenly, through his main window, I saw the guy with no arms walking slowly by on the sidewalk in front of Willard's house. The dog was nowhere to be seen. The guy stopped and stared at me standing like a goof in the window.

"Fuck!" I blurted out. "It's that freak. He's loitering around your house!"

Willard was completely unfazed, as if he'd dealt with the man numerous times. "Just ignore him. His kind are attention-seekers."

"His kind?"

"Like I said, he's not human," Willard repeated, as if reciting something on a menu.

"And you came to realize that during one of your LSD hits?"

He looked away from me, thoroughly uninterested. Then I noticed what he was doing. He was setting up an altar of some sort, upon which he had placed a black mirror, some candles, and a large piece of paper that seemed to have some symbol scrawled on it.

I turned around to look for the armless guy, but he was gone. A moment later however I was startled by the sound of a bark. I looked to the side of the building, from where the sound came. At that moment, a black dog lept at the window and bared its teeth at me.

"Jesus!" I yelled. "It's that fucking dog! That guy has sicked him on your house!"

The skies opened up and a downpour started. A flash of lightning, a peal of thunder, and then Willard killed the lights and lit some candles on his altar. His face appeared to reflect ghoulishly in the light of the black mirror.

He lit two sticks of thick incense. Within moments the room was full of smoke. I coughed. Willard began waving his arms about, nonchalantly mumbling "There are evil spirits in here."

"The fuck are you talking about?" I asked, creeped out by now. I glanced back at the street. In the dim light of the dusk I could make out the guy with no arms. He was back again, staring at Willard's house. His black mongrel had joined him, cocking its leg and pissing on a large bush.

Willard began performing a ritual, murmuring in what seemed to be Latin. The air in the room seemed charged. As his ritual reached its climax, the dog tilted its head back and howled. The armless guy yelled at it to shut up. It was the first sound I'd heard from him.

The rain let up, and the guy left. The dog did not initially follow him. I looked back at Willard. I had an intense moment of cognitive dissonance when I realized that the room was empty. I'd only glanced at the window for a few seconds, so it didn't make rational sense that Willard was suddenly not there.

I looked out the window again. Willard was standing on the sidewalk feeding the dog. He then slowly turned his head to stare at me standing in the window. In the encroaching darkness, I had a very strange hallucination. For a brief moment, looking at Willard, he appeared to have no arms.

Chapter 2

At that moment Willard motioned with his head that I should look in the direction from which the armless man had gone. I did so. I could make him out in the dim light of a street lamp about a hundred and fifty feet down the road. I blinked. The fucker suddenly had arms! He waved one of them at his dog, which then trotted off in his direction.

The shock I was feeling at that moment resulted in a suspension of my critical faculties, or what was left of them at that point. Willard looked back at me. The rain was coming down hard again. In the blur of the downpour he seemed to be laughing. I scanned his body, searching for arms, but I couldn’t see any. He was a goddamned amputee, I could have sworn it. He then disappeared around the corner of his house toward the back. I walked to his kitchen, which was situated in the back, and a moment later he barged in the back porch door, stamping his wet shoes on the ground. I stared at him. He certainly had arms. Nothing appeared amiss.

Willard blinked at me, then his lips curled into a mischievous smile. He seemed to know what was going on, the perceptual oddities I’d been experiencing. “Let’s get back to the ritual space,” he muttered, and we went back into his living room, where the incense was still burning and everything else (I gratefully noted) seemed as it was before.

He slouched down on a pile of couch pillows and began to talk. At first I was only half-listening, but as he continued, my clarity and capacity to listen came into focus. He was talking about perception.

“Perception is a multifaceted thing,” he was saying. “It depends on many factors, but mainly on your psychological filters. Most of the wisdom people throughout the centuries have been repeating the same thing over and over, that what you see is mainly your own mind, not anything like reality.”

“You mean like Plato’s Cave?” I offered tentatively.

He grunted. “Sure. But Plato was more concerned with sensory distortions – those shadows that the ignorant person perceives and judges as “reality” are lesser versions of reality distorted by our senses. The higher truths are knowable by clear reason, and so on. He lacked the sophisticated understandings of modern psychology, or even the idealism explained by Kant three hundred years ago.”

I was barely listening at that point. His voice had become something like a low-key drone, and I found myself preoccupied with the bizarre perceptual distortions I had just experienced. He looked at me quizzically, seemingly knowing what I was thinking. He then laughed.

“You want to know whether or not that crazy fucker with the dog really has arms, don’t you?” His eyes glinted in the candlelight. Outside, the rain continued to pound down.

I tried to carefully compose my words. “I could see that he had no arms. And then I saw that he did. He waved toward his damned dog. And at one point you had no arms, I swear.”

He smiled contentedly, like some toad basking in a weird accomplishment.

“As Bertrand Russell once said, too much certainty is the problem, not ignorance.”

“Fuck Bertrand Russell,” I grunted. “I know what I saw”.

He laughed again. “No you don’t, you pretentious wanker. All you know is that you saw something, not that you know you saw it.” He was clearly enjoying himself.

“What the hell is the difference?” I protested. “I saw something without judging what I was seeing. It was a naked observation. Therefore, I knew what I saw.”

“Without judging?” he sneered. “That’s where you make your mistake. We are always forming judgments about what we’re experiencing. Our minds are judgment machines. Anyone who claims otherwise is either a bullshitter or is ignorant of how their mind functions.”

I was getting hot under the collar, but I knew him well enough to suspect that he had some point in there worth looking at. I took a deep breath and considered what he was getting at.

We were quiet for a few moments, the only sound being that of the steady rain outside. Suddenly I was jolted back to the moment. Someone was banging on his front door.

Willard sighed and made a show of ignoring it, perhaps hoping whoever was banging would get the message that no one would be answering. But the thumping on the door continued. He got up slowly to answer it. I glanced at his face, and could see his eyes narrowing, as if he felt some strong presence on the other side of the door. Or maybe he was just pissed that he had to get up. I assumed that Willard was not the most social guy, and that he didn’t exactly have a large network of friends. (I was later to discover that that was not entirely true—his “associates”, as he tended to call them—were larger in number than I initially suspected).

Willard threw the door open, with the air of someone who expected that no one would be there. From where I sat on the ground my angle of view enabled me to see outside when the door was open. Sure enough, no one was there…or at least, no one appeared to be there. It was quite dark by this time, and the dim glow of the street lamps provided only minimal illumination of Willard’s front porch.

Willard slammed the door shut with disgust.

“What the hell was that?” I asked.

“Up to his tricks again,” muttered Willard.

“Who?” I asked.

“The guy you think has no arms, who else?” he replied.

I figured it was time to dig a bit. “So who the hell is that guy? You clearly know him.”

Willard ignored my question and got up and went into the kitchen. The incense had burned out, and the rain outside had calmed down to a light drizzle. It was dark, and in the candlelight of his living room a couple of his small gargoyle statues on the mantelpiece were casting weird shadows.

He came back with a two open beer bottles. This was a first. I knew Willard had a love of red wine—he was always drinking the stuff—but apparently he was a beer guy as well.

“Molson Canadian,” I grunted approvingly, able to make out the beer brand in the faint light.

“The only way to go,” he replied. “Much better than Labatt's.”

We sipped our beers. I was just about to start relaxing when the damn door started thumping again. I looked with alarm at Willard.

His reaction took me by surprise. I had expected him to be pissed off, but instead he slouched back on a cushion and started laughing uproariously. The more he laughed, the louder and more insistent the thumping went on. It was fast becoming ludicrous. I began to think he was really crazy, or worse, the whole thing was being orchestrated with the armless guy for some arcane purpose.

Then I had the reasonable thought that an armless guy could not be pounding a door, naturally. He must be kicking it. I then found myself absorbed in the consideration of whether or not these sounds were boots on the door, or fists. I reluctantly concluded that they sounded much more like fists.

I reported my considerations to Willard, in a loud voice, above the din of his laughter and the pounding on the door. He agreed. “Of course it’s fists, from the armless guy.” He smiled weirdly at me, and then had another fit of laughter, seemingly at his own pronouncement about a guy with no arms banging on his door.

Unable to take the racket much longer, I myself got up and went to the door. “Be careful!” Willard snapped, his mirth suddenly gone. “Remember, that guy is a lunatic.”

I didn’t care anymore. The pounding was becoming intolerable. I threw open the door and stared into the darkness.

There was no one there. Then I looked downward. I had a moment of extreme disorientation. A large cat with unusual markings was sitting there, staring up at me with gleaming green eyes. It then quickly shifted its gaze and trotted off into the darkness toward the side of the house, where it appeared to climb up a tree. As I watched it recede into the darkness, I couldn't avoid the matter of the cat's size. The damned thing seemed huge.

I went out onto the porch and peered around. I could see nothing in the dark, except shadows and outlines of shrubs and bushes on Willard’s front lawn. I heard him laughing.

"Get back in here!" he barked. I hesitated for a moment and then went back inside and shut the door. Immediately the rain started coming down heavier. I looked in Willard's direction. He was rolling up a cigarette with a serious expression.

"You don't mess with Goetic spirits," he murmured.

"What are you talking about?" I asked. "There was a fucking giant cat out there!"

He looked irritated, ignoring my comment about the cat entirely. "Those knocks, if you'd been paying attention, you would have realized were coming in threes."

I felt a chill up my spine. I had some vague understanding about the significance of "three knocks" in occult lore, especially among paranormal investigators -- something about a mocking version of the Holy Trinity -- but had more or less dismissed it as mumbo-jumbo unworthy of serious consideration by anyone with a modicum of training in critical thinking.

Any yet, in Willard's presence, and especially in his house, my capacity -- or more accurately, my desire -- for critical thinking tended to be suspended. It left me open to possibilities, even if I secretly suspected that these "possibilities" were mainly fancy and nonsense.

I looked at him. In the glow of the candlelight he looked vaguely sinister. He was only around 40 but his history in the trenches of Vietnam, his earlier struggles with alcoholism, and his failed marriage (he had two young daughters that he saw only twice a month) had left its toll. He looked older.

As I was watching him, I suddenly became aware of something that made my skin crawl. It all happened so fast, and was so vividly real, that I couldn't quite process it rationally. A hand had tapped the back of my neck three times -- gently, yet firmly. But there was absolutely no one behind me. I was sitting in an armchair about 10 feet from Willard.

Suddenly he stopped rolling his cigarette, and looked slowly into my eyes. He smiled thinly, as if he knew what just happened. His face did not look friendly. There was a coldness emanating from him that made my mind stop so totally that I felt as if I had shifted into an altered state of consciousness. And it was then that I became aware of some sort of bizarre sound coming from right behind me.

Willard turned his head and blew out the candles.

Chapter 3

The room was plunged into darkness. A very faint glow from the street lamps outside filtered in through the drawn curtains in Willard’s living room, lending a yellowish, ghostly ambience to everything. The strange rustling sound behind me stopped. Some ancient instinct overrode me in that moment, I became motionless—perhaps an echo of the motionlessness deemed best by our ancestors if under threat from something in the dark.

I initially resisted the urge to turn my head around and look behind me. But that resistance soon broke down. I turned around to look. As I more or less anticipated, I could see or detect nothing.

“Human sensory capacity in the dark is rather limited,” Willard suddenly said, in a dry tone. I heard his voice and then felt myself moving deeper within. My consciousness seemed to be altered in some fashion. I then became seized with the thought that Willard may have put some substance in the beer he had given me. I was about to give voice to that thought when the sound of his voice jolted me out of my reverie.

“You’re not high,” he said to my utter surprise. “You’re being engaged. You can only be engaged by the spirit realm if you shift the focus of your awareness from your usual thought patterns to…something else.”

I formulated the thought “what something else?” but didn’t actually verbalize it. To my astonishment he answered. He seemed to be reading my thoughts. I couldn’t decide which was more disturbing, that possibility, or the whole general atmosphere I found myself in.

“The something else” he went on, “is the Other Side. The term “Other Side” is a gross simplification of another order of reality that walks with us, like a shadow, but of which we are normally entirely unaware of. It is rich and vastly complex beyond our wildest dreams.”

The strange sound behind me suddenly returned. I got up and groped my way toward it, unable to restrain my curiosity much longer. My eyes were beginning to adjust to the dark and I could make out general outlines of the hallway behind me that led into the other part of his house.

I stumbled my way down the hallway. I detected the strange sound receding down the hallway as I followed it. It led toward what appeared to be a closet at the end of the hall. Some street light was filtering in from a bedroom window, and I could make out the contours of the closet door. It was slightly ajar.

I hesitated for a moment. Willard’s voice echoed faintly from the other side of the house, about 40 feet away. “Go ahead,” I heard him say.

I opened the closet door. I was greeted with a loud rustling and flapping sound. I flinched and recoiled backward in terror. It was a fucking bird!

In my backward recoil I fell down on the ground. The flapping was all around me. It seemed as if the bird was huge and angry. In the midst of trying to process what was happening, I suddenly became aware that Willard was standing behind me. He was laughing. Then he receded back toward his living room. The bird apparently followed him. I then heard the sound of his front door being thrown open. A moment later it slammed shut.

I got up and went to the living room. “The bird’s gone,” he was saying.

“What the hell was that?” I demanded. “That fucking thing was huge!”

“It was a rather large crow,” he snickered. “They get in sometimes through the chimney.”

I was exhausted by the general stress of the evening and fell into one of his large sitting chairs. I was about to entertain the thought that he’d told me earlier that the spirit he’d conjured, Agares, was associated with birds, when I slumped back, closed my eyes, and drifted off. When I woke up, it was morning. The rain had stopped. Sunlight was slanting in through an opening in the curtains.

Willard was nowhere to be seen. I gathered myself together and left his house and returned to my apartment that was a ten-minute walk away.

Chapter 4

At that stage of my life I was immersed in a discovery of new worlds, fueled in part with my disillusionment with conventional education. I had found Nietzsche and Jung and Crowley and Castaneda and Hesse and Gurdjieff and Rajneesh and Monroe and the Zen masters. But these teachers and writers were all abstract, distant figures, many already six feet under. It was the personal contact and guidance that I needed. Willard provided some of that, despite my consistent reservations about him and his mental health. He seemed to the classic “wounded healer”. “Damaged mystic” was also appropriate.

The janitor of my apartment building was a friendly gay man that I’ll call Juan Steiner. He was part Mexican, part German, a weird combination I used to think. As it happened, Juan was pretty good friends with Willard. I’d witnessed them together on a few occasions. Willard had a casual bearing with Juan that I didn’t see him strike with anyone else. Juan, who was a humorous guy, seemed to be good at humoring him.

One day I sat down with Juan in his unit after dropping off my monthly rent check. We chatted amiably about things and then the topic of Willard came up. I expressed my amazement about some of the phenomena I had experienced in Willard’s presence, despite the relatively short duration of my friendship with him.

Juan stared at me with wide eyes. Then he spoke in an animated fashion, with the tone of someone educating a naïve idiot.

“Willard is mentally ill,” he said, carefully emphasizing the last two words to underline his exasperation with me. “Be careful when you’re with him. He’s a sensitive guy but he has issues.”

He wasn’t saying anything I didn’t already suspect, but the brashness of his announcement took me off guard a bit. I didn’t have anything to immediately say.

A few days later I was sitting with Willard in a coffee shop, and I decided to repeat to him what Juan had said about his mental health. I figured if nothing else the way Willard might respond to this could give me more insight into his thought processes.

His response surprised me. He threw his head back and laughed. “That faggot has wanted to fuck me for a long time. He’s just frustrated.” Then his expression became tender. “But I love the guy. I’d take a bullet for him. He’s a dear.”

He looked off into the distance. Willard speaking about “taking a bullet” for someone held weight, given what he’d been through in ‘Nam. I chose not to pursue the matter.

He sipped his coffee then stared out the window into the distance. Then he looked at me and announced, “It’s time to see Bill.”

Old Bill, as we also called him, was in his early 80s, a Christian mystic who was mainly confined to a wheel chair. He had some sort of tube up his nose most of the time, which I always presumed was for oxygen. To call Bill a “Christian” was charitable, as his mysticism was based largely on a radical re-interpretation of both the Old and New Testaments. Mainstream Christians would likely have viewed him as a dangerous heretic. A few hundred years ago he might have been set ablaze, wheel chair and all.

Some people who knew Bill dismissed him as a crazy old coot, but others, including his devoted followers Marion and Georgia, were convinced he was a deeply realized spiritual master. Marion once told me, in hushed tones, that Bill had confided in her that he recalled a past life as a close disciple of the biblical Paul.

I had blinked at her. “The guy who wrote Corinthians?” I asked. “The very same,” she confided in a low voice. We had been sitting in a diner and she was mindful of the nosy server who kept hovering around our table like some curious owl. I decided to listen to her impassively, despite my reservations about reincarnation crap.

Old Bill claimed to have been blessed, at a young age, with some strangely enhanced vision whenever reading the Bible. He said that certain passages would be visually magnified, and would project out from the page, in larger font, three dimensionally. These “enhanced passages” were sections for him to pay special attention to. Or so he claimed.

Sitting with Old Bill for his “spiritual meetings” as they were called, was always a peculiar experience. He had a habit of fixing his gaze on his close student Marion, and never looking at anyone else. At times it would border on maddening. You would ask him a question, and he would immediately look at Marion only, and proceed to answer. I used to imagine that he was either feeding off of her energetically, or that, more likely, he was pathologically shy. Marion eventually assured me it was neither.

“He’s near the end, and he doesn’t want his energy disturbed by the impure vibrations of others,” she shrugged in a matter-of-fact tone. I could see that she had long ago given up summoning the wherewithal to pass judgment on him. “He’s highly sensitive, and looking deeply into the eyes of others presents horrors to him that at this point he doesn’t want to deal with.”

“Then why not wear shades?” I asked half-heartedly. “He could be the Ray Charles of gurus.”

“He likes the light,” she replied, smiling.

I had never been too impressed with Old Bill’s lectures, probably because I could not always understand them through his mumbling. But he had a devoted following. A group of about 25 people used to gather in his living room, hanging on his every word. One of the matters he used to focus on was the issue of “false prophets” that he maintained had corrupted and distorted the teachings of Jesus beyond all recognition. He saw himself as a link to the “real” message of Jesus.

That of course did not qualify him for any unique status. History was littered with the bones of would-be messiahs and interpreters of messiahs.

There was however a unique element to Old Bill’s meetings, and it was the thing that did impress me. It was his energy-transmissions. At the end of his lectures and Q&A, he would invite whoever wished to come before him and receive a blessing by touch. He would place his hands on your head, for perhaps 15 seconds, while murmuring some blessing words.

On one such occasion, while receiving his touch, my eyes rolled up spontaneously, and I found myself seemingly shifting in time and space. In my mind’s eye I was vividly reliving the crucifixion of Jesus 20 centuries ago. In this visionary landscape, there were two groups of people: Romans, and pitiful Jews in fear of the Romans. I belonged to the latter group. I saw myself as hunched over trying to pay respects to my dead or dying master on the cross, while these Roman guys in armor stood about like bored cops. Bored maybe, but they had the power. We had nothing but a leader being tortured.

Suddenly the vision ended, something like a TV being unplugged, and I opened my eyes. Old Bill was wheezing and didn’t look especially interested in me, or curious about what had happened to me. He seemed more interested in ending the meeting so he could doubtless take a piss.

The day that Willard and I went to see Old Bill was different, however. Willard had this remarkable ability to arrange private meetings with people who were normally inaccessible, or met only with groups, such as Bill. There was something about Willard that people recognized, and made them willing to give him time whenever he wanted it. It was all part of this perplexing power he seemed to have. Or maybe he was just an accomplished manipulator. Probably both, I figured.

We arrived at Old Bill’s house, which was on the outskirts of the South Shore of Montreal, bordering a forest, an hour or so before sunset. Willard pounded on the door and we waited. A moment later Bill’s close student Georgia answered. She was often there. I imagined that she spent at least half her time at his house.

Georgia immediately acknowledged Willard, with a reaction that seemed to be part respect and part unease. Willard’s reputation obviously preceded him. She glanced only quickly at me, as if I were some inconsequential Sancho Panza to Don Quixote.

“Come in,” she muttered. “He’s expecting you.”

I didn’t know what to make of that. Far as I knew Willard had not scheduled any visit. He had spontaneously declared that it was “time to visit Old Bill” and we had simply got in his car and made the 45-minute drive.

We were ushered down a hallway toward one of the back rooms. The house was old, some sort of rancher, infused with the scent of cedar. Wood was everywhere, along with pieces of strange art that appeared to be African or Haitian, far as I could guess.

Bill was waiting for us in a room that seemed to be his study. It was lined with books and more art. There was a work table of some sort, strewn with paper and colored pencils. It seemed as if he had been working on some sort of art project. An old typewriter perched on the corner of the table. It looked like one of those Underwood antiques.

Bill was in his wheelchair. He gestured gruffly for Willard to sit in the one chair in the room, opposite from him a few feet away. I was left to sit on the ground. I chose to lean against the wall by the door, about 12 feet from their proximity. I figured it gave me a good spot to both observe these two eccentrics having their tete a tete, and to possibly escape should things take some turn toward the Twilight Zone.

I looked around at the walls. There were some interesting black and white photos up of mysterious faces, presumably from Bill’s past. One of them was of a very young soldier, standing beside what looked like a primitive tank. A few other older soldier stood off to the side.

Bill noticed me looking at the photo. He cleared his throat, always the sign he was about to speak. “That’s me,” he said nonchalantly. “World War One, northern France, 1918, the battle of the Somme. Horrible war. We lost hundreds on that day alone. I was blessed to survive.”

“Is that a tank?” I asked.

“Yes,” Bill replied, “the very first ones used in combat. Big, ugly beasts, incredibly slow by today’s standards. They got the job done, at least to some extent. We soldiers were terrified of them, but we also appreciated that they were on our side. The Germans didn’t have any just yet.”

It was in

that moment that I understood the connection between Old Bill and Willard, both

being war vets. They’d seen some of the darkest angels of human nature. Perhaps

it’s what drove them into the mystical dimensions. Or perhaps it’s what made

them mentally ill. I didn’t have the experience at that time to appreciate that

both might have been possible. So I made the good-will decision to lean toward their mysticism

rather than their madness.

Chapter 5

I settled in for what I surmised would be an entertaining exchange. But as usual the details of my expectations were not met in the ways I imagined they might be.

Old Bill and Willard appeared to size each other up, like two weathered lions—one aged and decrepit but still commanding considerable power, the other some sort of rogue lion who had been scarred from fights that he never seemed to lose. And yet it was also clear that they had some sort of old and deep connection. These two clearly knew each other, in more than the conventional fashion.

My deliberations were interrupted by the sounds of their voices. Bill was saying something to Willard about what it took to avoid enemy fire. “You have to be like Kilgore in Apocalypse Now," he was saying, referring to Coppola’s movie about the Vietnam war that had come out just a few years before. “You need one of those weird lights around you.”

Willard was nodding his head, silently agreeing. Apparently another thing they had in common was that although they’d both witnessed battlefield atrocities and had both (out of necessity) killed people, neither of them had ever been hit by bullets or shrapnel. I had half-expected them to begin comparing bodily scars, like Robert Shaw’s “Quint” and Richard Dreyfuss’s “Hooper” in Jaws. But it turned out that their scars were mainly psychological.

“You had to be bright to stay out of the line of fire,” Bill was saying. At first I thought that he was using the word “bright” in the typical manner, to refer to intelligence. But it soon became evident that he meant something else. He was using the word to refer to the strength of one’s personal energy field. He referred to this energy as simply the “field”.

“A weak field makes you subject to the vampiric predations of humans,” he went on. “War is just a grossly exaggerated theatre for what is going on most of the time. And the main evils behind this are the organized religions and the politicians who are their puppets. Jesus is the Redeemer, the chief light of lights who came to get us out of this prison.”

Willard was listening politely to these somewhat mundane ramblings. Bill was old enough to be his grandfather, and Willard sort of treated him like that—deferred to him, absorbed his raw experience and wisdom, while probably retaining his own objections quietly.

As I was considering all this a bizarre thing began to unfold. It began when Bill suddenly became personal with Willard, and appeared to be passing on to him some very tailored teachings. To my frustration I couldn’t hear him clearly, as he had leaned toward Willard and lowered his voice. I decided to surreptitiously move closer, but to my shock I could not move my body. Something seemed to be gripping my arms and legs and effectively paralyzing me.

For a minute or so I found myself locked in place, while Bill continued murmuring to Willard. The sensation rapidly became uncomfortable. I decided that I had to say something. Just as I was about to speak, Bill stopped his murmuring and looked at me. I had the immediate sensation of something being released, and suddenly I had full movement again. The entire experience was profoundly eerie. Before I could ask about it Bill motioned me to come closer. I did so, sitting on the ground a few feet from him. He looked at me quizzically. I felt the space to speak and immediately questions began to pour out of me. I felt my mind working too fast, causing me to disconnect from the two of them.

Suddenly Bill looked over my left shoulder with a fierce expression on his face. He dark eyes seemed to grow even darker. At that moment I sensed an energy rippling down over my head. As it did so, my mind fell still. Struggle as I did, I could not generate a single thought. My mind was utterly blank.

I’m not sure how long this lasted for, as my experience of time also seemed to slow drastically. I felt my mind locked in some sort of power struggle with this force that Bill appeared to be directing or controlling. I attempted to speak out loud, but what came out of my mouth was gibberish—disconnected words and ideas. Then slowly I found my bearings and my thoughts seemed to become clearer. At that moment Bill looked away and the “energy” gripping my head disappeared.

Willard was looking on with an expression that seemed partly one of amusement, and partly one of respect. But I couldn’t tell if his respect was for Bill’s power, or my own tenacity in breaking free of Bill’s power.

I can’t

recall much else of consequence happening that evening. We ended up in Bill’s living room

with Georgia, drinking black coffee and chatting about the state of affairs in the

world. Georgia, a middle-aged woman and lawyer with considerable

life-experience, was going on about the declining spiritual state of the human

race, and how despite all our technological advances we were actually entering

a dark age. “The more technologically advanced we become,” she was saying, “the

spiritually weaker we become.” This seemed like a simplified position to me but

the more I thought about it the more I saw her point. Technology was enabling

us to live easier lives, was doing the work for us, so to speak, and as a

result we were less and less experiencing the strength that arises from having

to make real efforts. In retrospect, her words were remarkably prescient.

On the drive back to the city, I asked Willard about the effects that had happened to me in Bill’s presence.

“Bill is an old and very powerful soul,” he was saying. “But what you experienced today was more the effects of one of his helpers. He has a strong familiar.”

“A what?” I asked. I had heard the term before, but usually only in conjunction with the stereotypical witch and her toad or black cat. Old Bill, a Bible-mystic, didn’t fit that stereotype. And yet he unquestionably could create impressive energy-effects.

“A spirit that he controls. He’s made pacts with things. He’s not what he appears to be.”

There was a certainty in Willard’s tone that gave me goose bumps. I was taken with the thought that Bill may have sent one of these “familiars” to keep track of me. For what purpose I couldn’t imagine. I asked if he had the capacity to do that.

Willard lit a cigarette, and I joined him. After a few drags from both of us the car was filling up with smoke. I thought about Cheech and Chong’s Up In Smoke scene, before rolling down the window. “Roll down your damned window,” I coughed. Willard silently complied. Then he replied to my question about “traveling familiars.”

“Bill is a magus. A real one, not one of those wannabe tricksters from a John Fowles or Herman Hesse novel. A real magus is one who commands power over elementals and other unseen forces. He can really make things happen, and yes, if he wants, he can spy on you from a distance.”

The idea was disturbing. “For what purpose?” I wondered out loud, not expecting any terribly convincing answer. Even I could discern the potential moral complexities of any sort of reason for watching someone from a distance.

“Remote viewing was a prized skill in older, pre-scientific revolution times,” Willard was saying. “You might want to keep track of someone for any number of reasons. In your case, if in fact Bill does something like that, it would be to monitor your spiritual progress. He’s interested in you. He sees your potential.” Willard shot me a glance with a half-smile that didn’t conceal the irony of the whole idea of Bill taking interest in me, a 23-year-old university student currently working in a bagel bakery.

“Interested in what?” I asked.

“He sees karmic seeds in the personal energy field, or aura, of a person. He’s able to look deeply into a given seed and recognize if it will germinate, at some point, into something positive or negative. In you, he sees some very strong seeds that can become something very good or very bad, depending on which way the winds blow for you.”

“And he told you all this?”

“Yes, right there in his study when you couldn’t move,” Willard laughed. “What else did you think he was talking about?”

The idea

that Old Bill had really been passing on his observations about me, and not

Willard, while “freezing” my body, somehow made the whole thing more

intimidating.

"So he used one of these familiar-spirits to control my body and stop my mind?" I asked half-seriously, struggling to hold back my urge to blanket the whole real experience with skepticism.

"You felt it yourself. You know what I'm talking about," Willard answered with gravitas. Upon reflection, he was right. I was sure I could dismiss the whole thing as part of the power of suggestion that the subconscious can do so effectively. But try as I might, I could not deny the reality that I felt a damn presence around me exerting some sort of force on me. It was no fucking suggestion.

The rest of the drive back to the city was passed mainly in silence between us. Willard used to have CBC FM radio playing in his Chevy Nova, its staid programming always a bizarre contrast to his eccentric bohemian ways.

“Surprised you listen to that channel,” I remarked once.

“It settles my stomach,” he had replied.

I looked at him with raised eyebrows. “Your stomach?”

“Yes,” he said. “Like the Zen masters, I carry my mind in my stomach. My head I try to keep empty.”

Once back in the city, Willard stopped by St. Viateur’s bagel shop. For a guy who was working at rival Fairmount Bagel, this was sacrilege. But he had a penchant for doing these kinds of things, whatever might rub me on some fashion. He liked to “press corns” as Gurdjieff had called it.

While eating our bagels with lox and cream cheese in his car, I noticed a woman ambling in our direction. As she got closer, she moved toward Willard’s side of the car. She clearly knew him.

He greeted her effusively. He was always charming with the ladies, with the sole exception of a somewhat mysterious old spinster in his neighbourhood that he had some sort of running feud with. “Debbie!” he remarked warmly, “how are you?” She responded engagingly, and before I knew it, I had been relegated to the back seat while Willard schmoozed with her in the front. They went on and on, laughing and talking in an animated fashion about various matters. I was only listening absentmindedly, still caught up in the events at Bill's house.

“Fuck it,” I

thought, as I began to eat my way through our haul. “The bagels are good.”

Chapter 6

That point in my life was an extraordinary confluence of characters and events, which at the time made me deeply question the whole notion of free will as the rapidity of these events, compressed into mere months, suggested a destiny that was written in the stars. Be that as it may, it did not stop me from attempting to take careful stock of these characters, why I was drawn to them (or more mysteriously, they to me), and what exactly they represented.

The bizarre nature of many of the experiences had served to shake up my preconceptions of the nature of reality. My primary interests up to then were not completely involving analytical and linear ways of conceiving, via hard science, namely my passions of physics and astronomy—after all, I was also invested in art and creative writing. But unquestionably the analytical thinking predominated. My absorption in chess as a committed tournament player only reinforced this type of strategic and tactical thinking.

The latter pastime had almost consumed me wholesale, the sheer addictive power of chess only known to those few hapless fools who truly cross the threshold over into the realm of the 64 squares, its mysterious geometry, and the dancing cast of royal characters that shuffle about on its battlefield. In the late 1970s I used to frequent one of the great chess cafes of North America, Montreal’s Café En Passant, on St. Denis street. This smoky den of iniquity, featuring men crammed shoulder to shoulder on rickety old tables strewn with scuffed Staunton pieces and misplaced plastic green and white chessboards, a cheerful but hopelessly under-worked server (chess players are inclined to forget to eat when absorbed in multiple consecutive games over many hours), and smoke everywhere, heightened the cultic quality of the whole thing. “En Passant” in French literally means “in passing,” and in this case, refers to a specific chess rule, but the name also applied in other subtle ways that probably went over the head of most who played there.

I had a chess mentor in my early months as a neophyte. His name was Denis, which, given that the club was situated on St. Denis street, seemed a charming coincidence. He was a young architect with multiple passions that including cycling and restoring old classic cars. In my first few months playing the local patzers and hustlers and club pros, I used to lose all the time. Then gradually I started to understand the game and improve. I started beating guys I’d previously lost to. My ego pride began to surge, but my real breakthrough came when I finally beat Denis, my mentor, after what must have been 100 consecutive losses to him.

I still remember the look on his face when he conceded defeat, a classic combination of competitive anger and pride at what his protégé had accomplished. “I’ve never seen anyone improve as fast as you,” he remarked, which I imagined was the perfect remark to make to both save face and to genuinely recognize his charge. I took the compliment in measure, because despite eventually going on to win the Quebec college championship in 1979, I never could make a dent against the few bona fide chess masters in Montreal at that time.

Chess is a deeply humbling game, because no matter how good you get, you’re going to be beaten by someone better sooner or later. And no one can be good at chess without hundreds or thousands of hours of practice and study. You can’t sit down and play chess well with no previous experience of it anymore than you can sit down and play a violin well without ever having picked one up before.

The chess subculture is very hierarchical, players ranked by a rating system that assigns a number that will fluctuate, depending on tournament results. The weaker players—beginners or those with obvious lack of ability—were known as “fish”. The strongest players were the “masters,” of which there were very few. Between the fish and the masters was a vast range of skill, everything from the standard club player to Class A players to candidate masters.

Above the masters was the even more rarefied air of the “international masters” (IMs). A standard chess club like the Café En Passant might have one or two IMs present playing casual games at any give time. Beyond the IMs were the “grandmasters”. At the time I was frequenting the En Passant there might have been a couple of hundred grandmasters in the entire world out of millions of players, most of them concentrated in Europe and Russia. Canada had two, Duncan Suttles and Peter Biyiasis. Suttles was a recluse living in Vancouver, but Biyiasis was in Montreal at the time and on rare occasions would be present at the club. The table he played at would always attract a crowd, as he casually dismantled his opponent, and then explained after, in his faint Greek accent with a slightly aristocratic bearing, how he’d accomplished the deed. I don’t recall him losing a single game. Like many of the chess elite, he was something of a snob. He used to wax poetic about his games for the grubby contingent surrounding his table. “Ah, zees was one of my finest games!” he would regularly pronounce, then showing us in his detailed analysis, replaying the entire game from memory, why his opponent had been a fool.

Biyiasis had been Canadian champion in the early ‘70s, but his big claim to fame had been the fact that he was a major training partner for the infamous Bobby Fischer, the Soviet-slayer, who many regard as the greatest chess player of all time, his later descent into madness notwithstanding.

I once invited Willard to accompany me to the club for a visit. To my surprise he agreed. Turns out he had played the game before and had some basic skills. While at the club he played only one game, defeating one of the club players who was average at best in strength. Willard declined to play more. I wondered whether his ego wanted to escape after his one victory—get out while ahead kind of thing—but he later denied it. He said it was time to leave because of the general atmosphere.

“These guys are mainly neurotics, introverts flirting with madness, playing out unfinished psychological issues via their addiction to a game that largely replicates family patterns.”

I frowned at him, although his assessment didn’t entirely surprise me.

“Have you read Alexander Cockburn’s Chess and The Dance of Death?” he asked.

I hadn’t. Though if Willard mentioned it, I figured I now would.

“Cockburn presented a somewhat dim, Freudian interpretation of chess, the gist of which is that the king symbolizes the father, and the queen the mother, and that chess players are all acting out castration anxiety—the fear that their father is going to take away their manhood, as represented by the king, via checkmating him. With, of course, the aid of the mother, the queen.”

He looked wryly at me, waiting for me to respond. My frown deepened, which he seemed to find amusing.

“And remember Crowley,” he continued, with a look of satisfaction as if he was now playing a trump card that I’d find hard to refute. “He was an obsessive chess player in his youth, got to be near-master strength, thought about dedicating his life to the game. And then he had his big awakening when he walked into his chess club one day and realized with full force that it was not an option for him to spend his life consorting with such fools. I think his line was, ‘there but for the grace of God, went I, Aleister Crowley.’”

I could see the point. Any obsessive pursuit of a pastime, a game, would be bound to unbalance a person. Sensing all this I played in one last tournament, the ridiculously named Santa Claus Open, and then resolved to quit. Doubtless my sub-par performance didn’t hurt my decision. Nothing like losing to provide justification for change.

Not long after I wrote a short story called The Black Knight. It was my attempt to write something Kafka-esque, like the great Czech’s Metamorphosis. My story was all about a man who wakes up one day and realizes that he’s been transformed into a chess piece—a large wooden black knight. Although he is just a piece of wood, he has eyes of a sort, and can see. He finds himself in an empty room save for a large chessboard that he sits upon, and directly in front of him, a large oval ornate mirror. He is now destined to spend all of eternity gazing at himself in the mirror, unable to move. From there he goes into a prolonged reverie, living out what seems to be memories of some ancient past.

Willard listened to the story as I read it out to him. He seemed unimpressed. “You need to have more sex,” he murmured, lighting up a cigarette.

I could follow his reasoning. To exist as a chess piece in an empty room was one step above Dante’s ninth circle of Hell, where everything is frozen and motionless. Sex was a fluid act, a dance of interconnection between two water-beings.

I shared that thought with Willard. He smiled faintly. “Not bad,” he replied. “That can make up your next short story. Dance of the water-beings beats dance of death by far. Or stories about chess pieces sitting in front of a mirror like some frozen cock.”

He looked piercingly at me. The image drove the point home. Willard had spoken at length to me about sex and its role in the work of transformation. He had introduced me to the ideas of circulating energy up and down the spine, containing sexual release, controlling the ability to ejaculate only when one wants, or not at all in order to satisfy the woman, whose “inner Kali” then had a better chance to surface for the benefit of both, and all that Tantric blather that Western seekers were gobbling up at that time. But in all these conversations I could never discern whether he was operating from a higher plane of understanding, or whether he was secretly driven by his own dark impulses and disguising it all in the language of a sage.

I never really formed a conclusion on that, as I recognized that my relative youth disqualified me from fully understanding a man almost twice my age with twice my life-experience. I did however trust my basic instincts, and they informed me that Willard’s intentions were benign, even though he clearly still had his demons.

These demons used to emerge when he drank beyond a certain point. One night I was sitting alone in my apartment reading when there was a knock on my door. I opened it, and there stood Willard, bottle of red wine in hand. On occasions like that he wouldn’t bother to acknowledge whether I wanted to receive his company. He’d usually just barge right in.

He headed to my kitchen, grabbed two glasses, opened the bottle, and poured. Then he drank his glass without interruption. He looked at me. I was half-expecting some monologue about the great work of ego-loss, when he surprised me and took a different direction.

“Juan wants to have sex with me,” he said. “What do you think I should do?”

I couldn’t tell whether he was genuinely seeking my counsel, or whether he was speaking rhetorically as a means of provoking me into something.

“What do you want to do?” I ventured, figuring such a bland question would camouflage my bewilderment. I had assumed that Willard was pretty straight, based on his extensive experience with women, and the fact that I’d never seen him betray the slightest sexual interest in men.

He lit a cigarette, took a deep drag, and blew the smoke toward the kitchen window instead of into my face. This was sign that he was thinking differently.

“Some of the deepest occult initiations involve anal penetration,” he said, with a suddenness that caught me off guard. He laughed at my surprise.

“The point is all about transgression,” he went on. “The boundaries of the ego are problematic when it comes to rising on the Tree of Life. Different avenues sometimes need to be pursued to get past the various guardians that block the way forward. Old Crow himself made references to these guardians when he wrote about the need to find other methods to ‘roll away the stone’ in his monogram on hashish.”

“Guardians?” I asked. He hadn’t used the term before.

“Yes, guardians. These are the Archons that some schools of Gnostics talk about. Their job is to slow you down, cause problems, fuck with your mind, manipulate you, test you with bad luck, and so forth. That’s what Satan was up to with Job in the Old Testament.”

“What does getting fucked up the ass have to do with any of this?”

He grunted. “The association is not immediately obvious, granted. Are you familiar with the Osculum Infame?”

“The Osculum what?”

He smiled and downed another glass of wine. “Osculum Infame,” he repeated slowly, as if savouring the words. “It’s Latin for ‘kiss of shame’. In the Middle Ages it was believed that witches attended sabbaths at night in a deserted spot, like a forest or a grove, where they consorted and fornicated with the Devil. One of their most basic ritual acts was believed to be the kiss of shame, where the Devil bends over and the witches each take their turn kissing his ass.”

I was about to make some quip about pornography, when I had a flicker of recognition. I remembered seeing an old woodcut from a Renaissance book about witch persecutions that seemed to be connected to what he was talking about. I shared my thought with him.

“Yes,” he said. “The image you speak of is from the 15th century Malleus Maleficarum, or ‘Hammer of Witches’ as it was rather ironically translated. It was written by that maniac German monk Kramer. The book is full of weird psychosexual pathology projected onto so-called witches. Nevertheless, it does present a fascinating window into the word-view of western Europe at that time.”

“Why do you say so-called witches?”

“Because 95% of them weren’t. They were Christians in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

“This kiss of shame,” I ventured. “Might it not be a projection of the repressed homosexuality of the priesthoods?”

Willard smiled approvingly at me. “Very good, you’re starting to connect dots.”

“Connecting dots” was one of his favourite expressions, something he maintained that a true mystic was inclined to start doing more of, once their more sensitive faculties of discernment started to come online. I’m not sure my limited time spent with him qualified me for some sort of “increasing discernment” abilities, but something seemed to be rubbing off, despite his quirks. Or so I chose to believe.

“Yes, many of the monks became gay, you could say, over the prolonged periods of time in which their only company was other men. During the Dark Ages the monkhoods were the custodians of the so-called books of the sorcerers that had survived since the time of Christ. That queer Pope Sylvester of the 10th century was suspected of conjuring demons. The combination of homosexuality and having access to the secrets of the Devil made for some interesting results,” he laughed.

I sipped my wine. The taste was acrid. I disliked cheap wine, which seemed to be the only kind Willard ever bought. It wasn’t because he was poor. I’d heard rumours from Juan that Willard was quite well off, though he lived in a modest bungalow and drove an old car. He once told me he just preferred cheap wine. “No such thing as good tasting wine,” he had proclaimed. “It all tastes like soap or vinegar. Bordeaux, Burgundy, Pinot Noire—whatthefuckever. People brainwash themselves into thinking there is such a thing as great wine. There is cheap wine and expensive wine, but it’s all just soap and vinegar.”

“Then why drink it?” I’d asked.

“It’s good for the spirit,” he replied. “We humans have been drinking putrid grapes for almost 10,000 years. There’s a reason for that. It’s part of the sacrament in many traditions, not just Christian. Take Omar Khayyam, the 12th century Persian poet. Much of his Rubaiyat, the work translated by Fitzgerald, is him raving on and on about the spiritual value of wine.”

This comment interested me for other reasons. And Willard, who usually had an angle on something, had a pointed reason for sharing it with me. I was to find out, not long after, that he belonged to what he characterized as a “secret society” that went by the name “Ruby Yacht”.

“What is that, the gay mariner’s version of the Pequod?” I joked.

My quips to him often fell flat, but that one made him chuckle. “Not quite,” he replied. “Ruby Yacht is a play on Khayyam’s Rubaiyat. And no, it’s not a secret branch of AA either.”

He went on to tell me a bit about the society, and how it was comprised of a somewhat mysterious group of people scattered around the world who were part of what he characterized as an “underground” dedicated to studying the secret history and likely future destiny of the human race. Much of this study involved considerable sleuthing and travel to what he termed ‘power spots’.

“How many people are in the group?” I asked, half-expecting him to say himself and a few other societal outliers. His reply surprised me.

“It varies, but there is a committed core of around forty men and women. Some of the members are what would charitably be called eccentrics, but all are intelligent, dedicated, and capable of critical thinking—and some even have legitimate connections with people in power positions in the world. They range in professions from psychotherapists, teachers, lawyers, geologists, wealthy recluses, occultists, and computer engineers. And then we have our more extended associates, various contacts we have in historically important countries such as Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Greece, England, Tibet, and so forth.”

I looked at him holding a question in my mind, which he clearly read.

“You’re wondering about my involvement with the society,” he said. “Let’s just say that I have the Midas touch. I’ve been something of a benefactor to some members in the group. And I wear other hats as well, many of which you as of yet know nothing of.”

He had finished the sentence with an air of completion. It was evident he’d be saying no more about the topic for now. I looked at him quizzically.

“Everything in its own time,” he said. “So far you’ve gotten exactly as much as you can assimilate. Next week I’ll introduce you to a local member of the Ruby Yacht.”

Chapter 7

I knew a bit about secret societies at that point in my life, as I’d been inspired to read up on them after ploughing my way through most of Herman Hesse’s novels, especially Demian and Steppenwolf. It was the latter story, written by Hesse in the late 1920s, that would prove to be weirdly prescient as applied to my experiences with the Ruby Yacht.

Steppenwolf was all about a man who has to deal with the standard twin forces within every human, the exalted higher nature, and the lower bestial nature. It was the latter that Hesse had likened to a wolf of the steppes. In the novel the protagonist, Harry Haller, eventually is directed to a “Magic Theatre” where he encounters certain key characters who guide him into a deeper understanding of his nature.

Willard had arranged a coffee meet with he and I and a middle-aged woman named Barbara. He had mentioned her to me before, and about some of the work he had done with her and her husband Peter. They lived in a rural home somewhere between Montreal and Toronto, where they worked as Primal Therapists. Willard claimed that they were two of the “deepest people” that I would ever get to meet, and that their inner work with their students was not for everyone. He had also told me that they were long-standing members of the Ruby Yacht.

I decided to do my best to keep an open mind going into the meeting, as at that point I was becoming increasingly aware of the division within me of how I perceived and judged Willard. I had concluded that he was a genuine article in many ways, and clearly had access to knowledge and experience and people far outside normative life. On the other and, I could never quite shake a feeling of a certain unease around him, as it often felt as if he was reaching for something with me that I was not sure I could, or even wanted, to provide. Or perhaps I just felt unworthy of his attention. Nonetheless, I decided to lean toward good will in meeting people that he wanted me to meet, as there was always the possibility that they would present something of even greater quality than what Willard appeared to be offering.

Meeting Barbara, that instinct was confirmed. I immediately felt at ease around her, in a way that I rarely did with Willard, and moreover, I felt her power, a power that seemed to emanate from her in a natural fashion shaped by years of hard-earned wisdom.

Barbara was in her late 50s, with a pleasant, round face and an easy smile. At first glance she might have passed for the neighbourhood librarian. What marked her apart however were her eyes. They were light grey and had a depth and a fixed quality to them that suggested a lively intelligence and someone who could truly pay attention and understand another person beyond the usual superficial acknowledgements. She also spoke with a clarity and gentle conviction that added to the quality of self-confidence that she emitted.

While the three of us sat around a table in the café, the discussion somehow became steered to the topic of ceremonial magic. It was an area of esoteric work that I was only marginally familiar with on a theoretical level. I had my copy of Crowley’s classic Magic in Theory and Practice, though much of it went over my head.

Barbara was talking about the role of the Holy Guardian Angel in ceremonial magic, or the “Angel” or “higher self” as it was variously called, and how it was something difficult to access for a seeker who had not gone through what she called their “primal issues” first. I pressed her on what she meant by “primal issues.”

“The greatest trauma in life is generally the birth process,” she said. “It is the great barrier to cross, and for the incoming soul is both exhilarating and terrifying. It is also where our primary patterns that we will face in our life take root. For example, if your parents were ambivalent about having you, or even if the attending doctors and nurses were carrying negativity, the infant absorbs all that to some degree, leading to direct imprinting about how safe the world is, how safe it is to be alive, is one supported in life, and so forth. And in most situations, especially in the industrialized West, such negative imprinting via birth is common.”

She paused, to take measure of how I was receiving her words. This was a quality that to me immediately marked her as a developed person. So many people talk at a person, rather than being sensitized to the reality of the person in front of them. That said, Barbara was no caretaker. She also had a blunt manner to her that suggested to me that she would exercise empathy only to a point and would abandon it if it was clear that the person she spoke to misused it in even the slightest.