Wild Wild Times

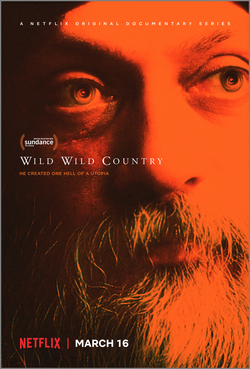

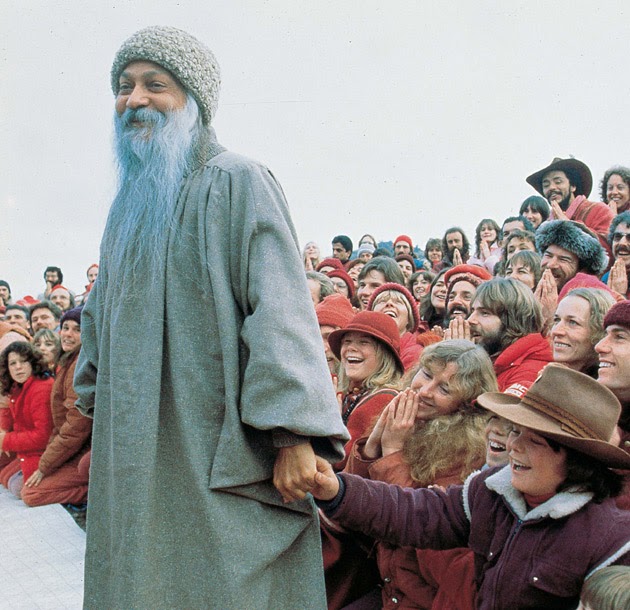

The documentary Wild Wild Country, directed by the talented team of Chapman and Maclain Way, is a six- hour Netflix docu-series chronicling the dramatic events that engulfed the Oregon commune of controversial Indian mystic Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh (a.k.a. Osho), from 1981 to 1985.

The documentary Wild Wild Country, directed by the talented team of Chapman and Maclain Way, is a six- hour Netflix docu-series chronicling the dramatic events that engulfed the Oregon commune of controversial Indian mystic Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh (a.k.a. Osho), from 1981 to 1985.

I was initiated as a disciple of Osho in February of 1983. I experienced first-hand some of the events described in this documentary in Oregon. I also published a book on Osho in November of 2010 (The Three Dangerous Magi: Osho, Gurdjieff, Crowley, Axis Mundi Books). Some people asked for my remarks on the documentary. I’ve made a few comments, and at the end, have added on a chapter from my 2010 book on the Oregon commune.

The documentary is put together with professional skill and talent. It’s very watchable. The pace is a bit on the quick side, consistent with the reduced attention spans of current audiences. But it avoids any dumbing-down tendencies. The real ‘gem’ of the documentary is the archival footage that the filmmakers were offered to use — hours and hours of it, much of it detailing with startling accuracy what was going on, a kind of time-machine back to the early 1980s.

The major weakness of the documentary—something that has been touched on by others I know who’ve watched it but have no background with Osho—is the lack of groundwork laid out explaining just why Osho was such a draw in the first place. This lack of groundwork becomes understandable when you bear in mind that the two filmmakers are young (around 30) and until 2014 they had never heard of Osho. It’s not possible to grasp Osho in a year or two of intense study, so it’s remarkable that they were able to produce a documentary of this caliber at all.

While the Way brothers attempted to explain Osho and his background in episode 1 (probably the slowest of the 6 episodes), it’s essentially impossible to capture his presence, power, and magnetic charisma in a one-hour episode. That said, the documentary picks up powerfully in Episode 2, and probably is at its strongest at the end of episode 3, when Niren (Osho’s lawyer) concludes with his cryptic remark about how ‘we all have a dark side…but that doesn’t mean we’re bad people.’ It’s a superb scene, especially with his added-on cackle that could be read as either deeply wise, or just plain sinister. These kinds of scenes can’t be scripted or acted better, one of the powers of real-time documentaries.

One other problem: the filmmakers referred to the ‘two sides’ getting equal airtime in the show (which, arguably, they did). However, there were not just ‘two sides’. There were three important sides—the American government, Sheela’s clique, and the Lao Tzu house residents (which included, of course, Osho himself). What the documentary lacked was any real insight shared by the latter group. What would have rounded it all out a bit more would have been some interviews with George Meredith (Devaraj, Osho's doctor--the same one who was targeted for assassination) or Juliet Foreman (Maneesha, one of Osho's chief chroniclers).

That said, I think it was something of a stroke of genius to give Sheela and Shanti Bhadra the interview time that they did, because it really made for the ‘alchemical conjunction of opposites’ to play out. Always more interesting when you have the contrasts from opposites, as they make each other more vivid just by standing together. The moon shines brightest when opposite from the sun. In that sense, I think this documentary is more effective for sannyasins to watch than it is for newcomers. The latter will be entertained, for sure, but will gain little in understanding of Osho. But for sannyasins, the views into Sheela’s mind are revealing and for me at least, filled in some key blanks to the whole story.

The downfall of Rajneeshpuram had its genesis in a long series of factors, but key events were the bombing of the Rajneesh Portland Hotel in 1983, followed by the arming of the Ranch. Sheela remarked, as she ordered the training of some sannyasins in gun usage and marksmanship, that it would be ‘pathetic if we did nothing’. This militancy was intensely double-edged. It hinted at her fierce courage, but also showed the planting of the seeds of the commune’s downfall.

Further issues were the assault on her by one of the homeless men, while, as she described it, no one moved to aid her. These events took their toll. But the straw that broke the back for her was the arrival of Hasya and John, two wealthy Hollywood disciples whose power and influence gained them close access to Osho. The jealousy overwhelmed her, and her subsequent actions become increasingly irrational and dangerous. What was also appalling was her lack of contrition or remorse for the poisoning of salad bars that she and her lieutenants had engineered in the Oregon town of The Dalles, in a misguided attempt to keep voters from voting.

For me, the most disturbing moment probably came when listening to Shanti Bhadra talk about her attempted murder of Devaraj (Bhagwan’s doctor), and how she performed this act without empathy and driven by her emotional allegiance to Sheela. All of this was based on some audio tapes Sheela heard of what she thought was Bhagwan and Devaraj planning some sort of suicide for Bhagwan. You really see that this was where Sheela was breaking down. The woman needed therapy and support but wielded too much power for others to see or act on that (and this is regardless of what was really going on with Bhagwan).

The other thing that has been pointed out by some reviewers from various print journals and which I think absolutely bears repeating, is just how fixed the major players remain in their views, reminding me of Yeats’ famous line, ‘The best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity.’ I met so many quality sannyasins over the years who were humble, quiet, true representatives of what Bhagwan was supposedly standing for all that time. And yet the loud ones are all that are remembered.

In fact, Yeats’ whole stanza, written in 1919, was strangely foreshadowing of Rajneeshpuram:

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

In late October of 1985—where the documentary basically leaves off—Bhagwan left Oregon and returned to India, where he stayed in the north, in Kulu-Manali, for a short while. Meanwhile, I’d flown to India on my own shortly after he left. We had been told not to follow Bhagwan to India, but never having been a typical follower, I did so anyway. That, and I wanted to see India as I’d missed the first part of the experiment in Poona in the ‘70s. I went to Delhi, Agra, and north to Kashmir and Ladakh, where I ambled around the Himalayas and visited Tibetan Buddhist monasteries. After a while, I went south to Bombay, and then finally to Poona, arriving in late December of 1985.

The Poona ashram at that time was a ghost-ashram, run by a skeleton crew of perhaps twenty loyal Indian disciples. They kept it generally clean, but over four years of lack of activity had taken its toll. Weeds were growing through cracks in the floor in Buddha Hall, where Bhagwan had given his daily lectures from 1974 to 1981. But the cafeteria was still operational, and every evening a small group gathered to watch videos of Bhagwan’s talks on a cheap TV screen. I stayed there for a month or so, making some good friends and spending the time going deep into meditation. Then, one day word came that Bhagwan had gone to Nepal, and that sannyasins were welcome to visit him there, in Kathmandu. A few of us scrambled to book flights. We were there within a few days. I still remember the flight into Kathmandu, with Mt. Everest visible in the distance.

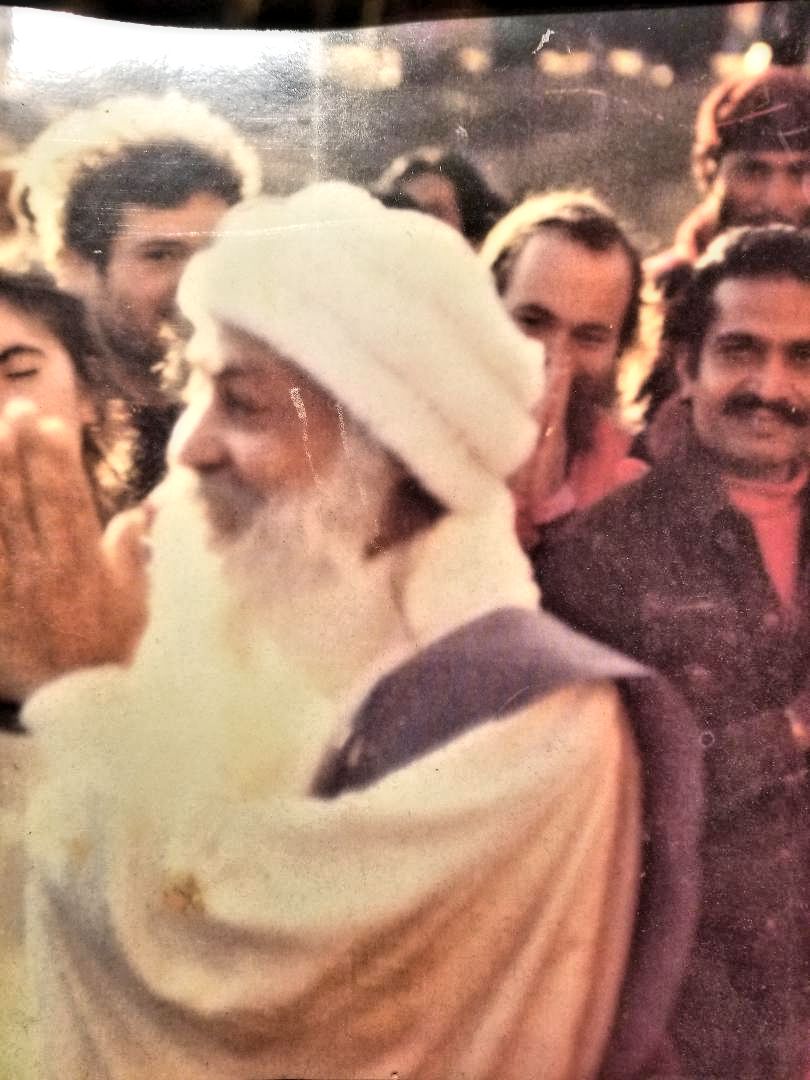

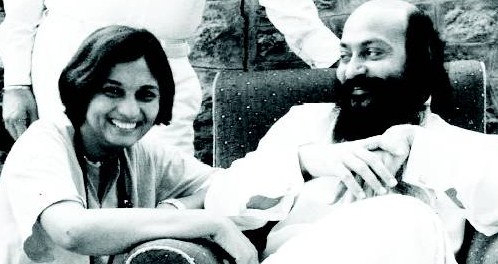

The photo on the right has an interesting story. That’s me directly behind the back of Bhagwan’s head, my hands in namaste. It’s from February 1986, on the grounds of the Soaltee Oberoi Hotel in Kathmandu. At the time I had no idea the picture was taken. A few days later I went for a walk in Kathmandu. While ambling by some bazaars and stalls that were crammed with stuff, I passed one table upon which were piled hundreds of photos. This photo was just lying there, on top of the pile. I always thought of it as a strange and unlikely gift.

The photo on the right has an interesting story. That’s me directly behind the back of Bhagwan’s head, my hands in namaste. It’s from February 1986, on the grounds of the Soaltee Oberoi Hotel in Kathmandu. At the time I had no idea the picture was taken. A few days later I went for a walk in Kathmandu. While ambling by some bazaars and stalls that were crammed with stuff, I passed one table upon which were piled hundreds of photos. This photo was just lying there, on top of the pile. I always thought of it as a strange and unlikely gift.

Below follows the chapter I wrote on Rajneeshpuram from my book The Three Dangerous Magi (Axis Mundi Books, 2010). This chapter was written in 2009, by which time the relevant facts were known and understood. The documentary Wild Wild Country covers most of these facts. The main thing in my chapter that you won’t find in the documentary is my own psychological interpretation of the relationship between Osho and Sheela.

The Spiritual Commune: Paradiso and Inferno

History: an account mostly false, of events mostly unimportant,

which are brought about by rulers mostly knaves, and soldiers mostly fools.

—Ambrose Bierce, The Devil’s Dictionary

The distinction between freedom and liberty is not accurately known;

naturalists have never been able to find a living specimen of either.

—Ambrose Bierce, The Devil’s Dictionary

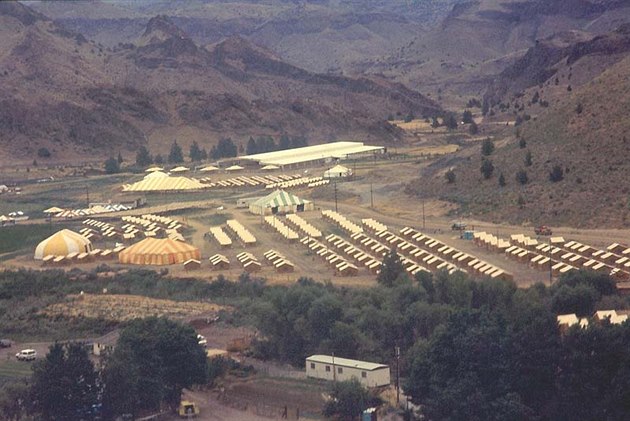

The commune built by Osho’s disciples in central Oregon in 1981 was arguably one of the most interesting and controversial intentional communities ever created. I was there at separate times in 1984 and 1985.

I worked in landscaping and was a daily participant in meditations and other activities. What I can attest to is the extreme intensity of the place, a sort of undercurrent buzz beneath the more outward show of meditative calmness or flamboyant celebration. I can also assert the following: the place was a bona fide mystery school, that is, an alchemical laboratory for working on oneself, but in order for that to be clear you had to understand a few things. First, you were entirely on your own. The commune was not an especially social place, and not at all from the conventional point of view. I remember more than once visiting the “disco dance” area and the usual thing to witness there was the vast majority of people dancing on their own—in their “own space” as the expression had it. And this was true of the place in general. If you went out for a walk in the small town (and it was indeed a town) you would mostly encounter people walking on their own, and most of these people were not inclined to be social—and certainly not in the usual artificial way. I emphasize these points to help dispel the myth that the Oregon commune was some sort of “free love/sex cult,” a slightly more Eastern version of a late 1960s hippie commune. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Whatever has been said about the place—and naturally, due to its spectacular collapse most of that has been negative—it was still fundamentally a place based on the meditative spirit. It was not a “feel-good” community (not by a long shot); it was mostly based on hard physical work, and the prevailing overall atmosphere was one of being pushed into self-observation. It was, if in that respect only, very Gurdjieffian but also very much like a more conventional Buddhist monastery, especially of the Zen type. I have spent time in both Gurdjieff communities and Buddhist monasteries and can attest to the similarities.

That said there were elements to the Oregon commune that were radically different from anything found in the Gurdjieff Work or Buddhist communities. There was definitely a celebratory atmosphere at times, and there was a strong Tantric component—not of the absolutely vama marga (left hand) type because the commune was strictly vegetarian—but this was not a community of celibates. Even with the beginning of the AIDS scare at that time and despite strict precautions taken by the commune to minimize the possibility of the transmission of disease, it was still a place that embraced sexual freedom. In addition, the whole commune existed in the shadow of a draconian leadership, the general strategy and tactics of which were not, it appears, fully known for some time by Osho himself.

I can also confirm is that the commune was being illegally buzzed by American fighter jets that roared overhead unannounced and at incredibly low altitudes, practically damaging your ear drums in the process (according several researchers these were from Whidbey Island Naval Base near Seattle; the purpose was to intimidate commune members and at the same time use commune buildings as targets for simulating bombing run trainings). On one such occasion I could easily make out the pilot inside as he flashed over my head. In addition, there were other, sinister developments arising from within the commune. I myself was something of a “troublemaker” disciple and was in hot water more than once with the commune authorities. On one occasion I was told to leave by one of the leadership “lieutenants” prior to the sudden collapse of the commune in September 1985. I resisted and had an intense encounter with this person. On another occasion I was followed by a commune helicopter for a lengthy stretch of empty road where I was the only person around; this came shortly after I’d been asked to leave (and had refused). There were other coercive tactics. I see these neutrally now, knowing that at the time the commune administration probably had their hands full what with the daily death threats against Osho from surrounding Oregonians. Difficult disciples from within their own ranks were doubtless cause for further unwanted tension. When the commune collapsed in a legal firestorm and internal corruption in the autumn of ’85 it was tempting to feel righteous, but that too missed the point. It was all, as many later correctly saw it, above all an opportunity for individual transformation. Despite all that happened there it remains for me a memory of a fascinating mystery school. And it is to the story of this commune that we now turn.

Rajneeshpuram: City of the Lord of the Full Moon

Osho had quit his post as a university professor in 1966 to devote himself full time to spiritual teaching (made possible by the support of some followers). By 1970 he had settled in a large apartment in Mumbai, but it wasn’t until 1974 that he established his first commune, or ashram, as they are known in India. By the late 1970s as the world-wide number of his followers swelled into the tens of thousands, the need for more space became apparent. Emissaries were dispatched to various parts of India to find appropriate land for the “new commune.” At that point however Osho was falling out of favour with the government of Morarji Desai due to various reasons, partly related to Osho’s incisive criticisms of organized religions and politicians (and not to mention of Desai himself—he was fond of mocking Desai’s Ayurvedic practice of “drinking his own piss”).

Throughout the 1970s Osho’s chief administrator had been Ma Yoga Laxmi, but by 1981 in what would prove to be a fateful change, she was displaced by Sheela Silverman (Ma Anand Sheela). Sheela, a young woman of just over thirty years of age, had a fire and drive that Laxmi didn’t, and Osho saw in her someone he judged to have the right characteristics to lead the administration of his organization through the next crucial phase of its growth.

Osho’s many troublesome issues with his body began to plague him seriously in May of 1981 when at forty-nine years of age he was diagnosed with a chronic lower back ailment (a degenerative disc). He then made what would turn out to be a decision that would bear serious consequences—he decided to go into an extended silence, ceasing the daily lectures that he’d been giving for the past seven years. (There is an interesting parallel here with Gurdjieff’s similar phase of prolonged withdrawal from his students following his serious car crash in 1924—a withdrawal that also proved to have a pivotal effect on the future of his work). Osho’s silence would last for three and a half years.

That same month a decision was made to fly him to the United States to treat his back condition—he was issued a medical visa based on the claim he was going there for medical help. He arrived in New York on June 1st, 1981 and was ushered to one of his many worldwide centers, a building in Montclair, New Jersey that had been designed to resemble a medieval castle. He and his group of caretaker disciples stayed there for a few months. They first considered relocating to a piece of land one of the disciples had found in New Mexico, but Osho rejected that idea.(1) Shortly after that Sheela found and purchased a large parcel of land in the central wastelands of Oregon. Called the “Big Muddy Ranch” by locals and notorious for its poor quality of soil and sparse vegetation, the place was deemed attractive due to its remoteness, and to the possibilities it presented for building something from scratch that could conform to Osho’s ultimate vision of a commune of awakened ones. It was very large, 64,229 acres, which is equivalent to a square of land approximately eleven miles long by eleven miles wide. As an analogy, a piece of land this size could fit seventy-five Central Parks and is half the size of all of San Francisco. The ranch was situated about eighteen miles southeast of Antelope, a tiny hamlet of around forty mostly retired folks.

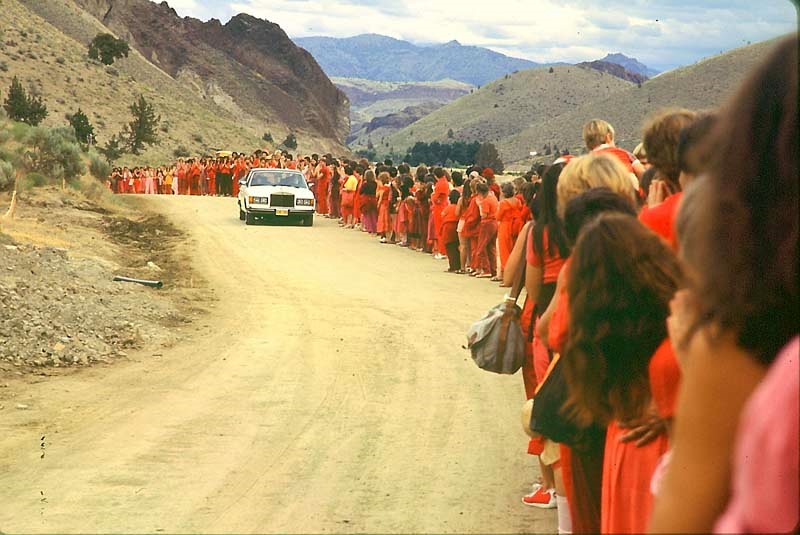

This ranch was soon transformed and maintained by a small army of grunt disciples performing gruelling labour, typically twelve hours per days, seven days per week, into a fully operational town—complete with hospital, post office, school, airport, and its own police force—that could sustain several thousand residents. During this time (‘81-‘84) Osho did not give lectures or meet with disciples. His sole means of contact with them was via the daily “drive-by” in which disciples would line the side of the road as he cruised slowly by in one of his Rolls Royces, sharing a smiling communion with devotees excited to catch a glimpse of their master.

This ranch was soon transformed and maintained by a small army of grunt disciples performing gruelling labour, typically twelve hours per days, seven days per week, into a fully operational town—complete with hospital, post office, school, airport, and its own police force—that could sustain several thousand residents. During this time (‘81-‘84) Osho did not give lectures or meet with disciples. His sole means of contact with them was via the daily “drive-by” in which disciples would line the side of the road as he cruised slowly by in one of his Rolls Royces, sharing a smiling communion with devotees excited to catch a glimpse of their master.

The commune was given the name “Rajneeshpuram” (puram='city', rajneesh='king of the night', or the moon; the name therefore means 'City of the King of the Night' or 'City of the Lord of the Full Moon'). It was legally incorporated as a city (although this was hotly disputed by certain government agencies—see below). First and foremost, however, the purpose of the commune was for it to function as a mystery school, a site for disciples of Osho to gather and work on themselves. In addition to all the trappings of a small town two central features were Rajneesh Mandir and the “Multiversity,” which included the therapy chambers. The first was a very large outdoor auditorium that served as a meeting place in which to do group meditations, attend satsangs (2), watch videos of Osho’s lectures, and after late 1984 when Osho broke his silence, to attend his live lectures. The Multiversity was arguably equally important. Not only was it extremely profitable, pulling in millions of dollars a year—money needed to finance the construction, maintenance, and expansion of the commune—is also played a key role in the social dynamics of the commune. The therapy groups were, in many ways, the most effective means of developing relationships within the commune. As mentioned it was not a place just to “connect” with people—it was a place for sincere seekers of truth and thus the emphasis was always on such qualities as authenticity, work on oneself, awareness of the moment, being “in the body” (i.e., truly present), and so forth. For most disciples the best place to develop these qualities was through a combination of experiencing the therapy groups, meditation, and hard work. And, of course, through the all-important connection with the master, which was the main defining point that brought everyone together.

Rajneeshpuram survived for just over four years. During that time it accomplished many remarkable things—transforming dead land into successful and self-sustaining dairy and poultry farms, creating entire irrigation systems, power substations, transportation, and telecommunications systems being just some of them—to the point that it has been commonly recognized as one of the greatest modern examples of intentional community. Alas, it all collapsed rapidly in the autumn of 1985 in a flurry of criminal activities. In brief the worst of it involved the following: Sheela and a close group of associates, convinced that a nefarious plan involving outside forces and/or Osho’s closest disciples was afoot to assassinate the master himself, attempted to kill Osho’s personal doctor (Devaraj), poisoned his caretaker (Vivek), conducted illegal wiretapping (much of the commune was bugged, including Osho’s own bedroom), and poisoned a salad bar in a restaurant in the Oregon city of The Dalles, sickening over 700 people, in a misguided attempt to prevent voters from voting in a key state election.(3) (Despite all the poisonings, somewhat miraculously no one actually died in connection with these crimes, either in the commune, or outside of it).

Rajneeshpuram survived for just over four years. During that time it accomplished many remarkable things—transforming dead land into successful and self-sustaining dairy and poultry farms, creating entire irrigation systems, power substations, transportation, and telecommunications systems being just some of them—to the point that it has been commonly recognized as one of the greatest modern examples of intentional community. Alas, it all collapsed rapidly in the autumn of 1985 in a flurry of criminal activities. In brief the worst of it involved the following: Sheela and a close group of associates, convinced that a nefarious plan involving outside forces and/or Osho’s closest disciples was afoot to assassinate the master himself, attempted to kill Osho’s personal doctor (Devaraj), poisoned his caretaker (Vivek), conducted illegal wiretapping (much of the commune was bugged, including Osho’s own bedroom), and poisoned a salad bar in a restaurant in the Oregon city of The Dalles, sickening over 700 people, in a misguided attempt to prevent voters from voting in a key state election.(3) (Despite all the poisonings, somewhat miraculously no one actually died in connection with these crimes, either in the commune, or outside of it).

Those were only the most spectacular and flagrant transgressions. Endless “lesser” abuses of power were ongoing. In the end, Osho claimed that he was unaware of Sheela’s activities and when he found out he invited the FBI and other authorities into the commune to investigate. Shortly before this happened Sheela and about ten others fled the commune in September of ’85. Sheela went to Germany but was later arrested and extradited to the United States, where she served just over two years of a twenty year sentence. Osho, after a strange sequence of events in which he suddenly left the commune, was arrested (along with a few disciples who were with him) in North Carolina, then transported slowly across the states back to Oregon, being forced to stay in a number of jails along the way. Once back in Oregon, on the advice of his lawyers, he pleaded guilty to the crimes of falsifying his visa documents and arranging sham marriages. He was fined $400,000 and deported. He returned to India with his inner circle of caretaker disciples. No evidence to link him with the more serious crimes was ever found.(4)

Three Poisons and a Wild Card

What went wrong? Despite the original lofty intention behind the commune—as a sacred meeting ground for Osho’s disciples to practice and follow his teachings while being near their master at the same time—numerous troubles soon arose to interfere with that spiritual mandate. Three obvious and potent problems in particular began to develop, all of which combined to destroy the commune within those four years. These were, in short, political opposition from surrounding governmental forces, Sheela’s own psychological state and her “application” of Osho’s teachings, and a deadly rift from within, between two key commune factions. There is a fourth, wild card issue, one that concerns Osho himself, and the degree of his responsibility; that will be discussed below. For now, let’s take a closer look at the “three poisons”:

1. The presence of Osho’s disciples in this conservative part of America was never welcomed, doubtless aided by the fact that these were, by and large, intelligent, educated, attractive young adults, not drugged out hippies or adolescents with shaven heads chanting Hare Krishna. Further, a significant number of Osho’s followers were affluent (though the majority were not), and most of these had willingly put their considerable material wealth at the disposal of Osho’s work. Inflaming all this was that Osho was not a typical polite Eastern guru—especially during his lectures of the concluding Poona years of the late 1970s-early 80s he had been a fiery outspoken critic of politicians and organized religions in particular. To top it off he would flaunt the wealth of his organization in part via his slowly growing collection of Rolls Royce cars (the ultimate symbol of decadence), and to really rub it in, his philosophy both allowed for and encouraged disciples to explore sex deeply and fully. He was seen as a hedonist who eloquently condemned Christianity and politicians. A more provocative man could scarcely be imagined.

But that was not all. A key element of Osho’s movement was the requirement of all disciples to wear shades of red and a mala with a locket that contained a photo of Osho’s face. The reddish clothing was not exceptional—committed members of religious groups (most notably monks and nuns) have worn only certain colors for centuries. Nor was the mala of one hundred and eight beads particularly noteworthy, that again being something traditional and common, specifically in the East. But a photograph of one’s guru in a locket dangling from such a mala was not common—in fact, it was essentially unheard of, even in Asia, where behaviour toward one’s guru that seems subservient is relatively common.

Most of Western civilization—and we refer here to Western Europe and North America—has its roots in Roman and Greek history. A typical element of Greek conditioning in particular has been the idea of the rebel, the hero who battles gods, who defines himself or herself via conflict and contrast with others. It is the archetype of independence. In much of the world the prime sense of responsibility is toward the family (India being a good example), or toward the nation (as in China), but in the West the prime responsibility—at least as the ideal to be aspired to—is toward the individual. America in particular represents the culmination of that ideal, having been birthed via a violent revolution that tore it away from its British roots. For Americans freedom is the chief ideal, and even if that ideal has been only marginally realized in reality—and probably not at all for the typical American—it remains omnipresent in the background, rendering suspicious anything that appears to be suggestive of loss of individuality. Needless to say, there is great hypocrisy within all this, especially amongst the staggering socio-economic inequalities of a capitalist society, where a tiny minority of people own and control the majority of everything. But despite all that the average small-town American is conditioned to be deeply suspicious of anything remotely resembling a form of devotion that, a) appears to minimize the individual, and b) is obviously foreign.

The idea of “minimizing the individual” was not actually what Osho taught—he taught, as he repeatedly pointed out, the minimization of the ego and the promotion of the individual—but his method in that was unabashedly Eastern and the reality is that for most Americans, including the media, this method was too foreign and threatening. The man in the locket must be a sinister manipulator with a gargantuan ego, the people wearing his locket must be brainwashed, case closed.

Owing to all that and more Osho’s movement was, as mentioned, never truly welcome in Oregon. From the beginning officials at the highest level of Oregonian government were investigating ways to have the commune shut down. The attorney general of Oregon at the time, Dave Frohnmayer, was an immediate adversary and attempted to legally invalidate Rajneeshpuram’s incorporation as a city by proving that it amounted to an unconstitutional merging of church and state. The Supreme Court eventually agreed with Frohnmayer, rendering the incorporation of the commune invalid, but their decision came in 1986 and was academic at that point, coming after internal events had already transpired to bring down the commune in ’85.

In addition to Frohnmayer’s efforts the environmental group “1,000 Friends of Oregon” opposed the commune on the basis of its commercial activities on the land and sought also to invalidate its incorporation on that basis. Along with all this there were regular threats of violence, and the Rajneesh Hotel in Portland was bombed in 1983 (although the bomber blundered, setting his device off prematurely and ended up maiming himself; no one else was injured).

Complicating all this was a series of events centered on the tiny village of Antelope, the closest community outside of the commune. Osho’s disciples gradually took over this hamlet, by legal means that derived from some of them getting elected to the Antelope school board, and from some of them buying real estate. All this was seen as threatening by state-level officials (including Oregon’s senators, who were now actively involved), and the effort to be rid of the commune was intensified. When the Antelope town council was taken over by Osho’s disciples, and in a dubious decision the entire town renamed the “City of Rajneesh,” it all added to the inflammatory mix.

Max Brecher, in his exhaustively researched 1993 book A Passage to America, concluded that there were high level conspiracies—all the way up to the Vatican—to shut down the Oregon commune from the beginning. Suspicions were rampant about the commune’s seemingly inexhaustible supply of cash, suspected to be connected to illicit activities (drugs, etc.), although most of this money was coming from a number of highly successful European businesses (Osho restaurants and discos, mostly in Germany), and the Multiversity programs which were almost always booked up. Rumors of stockpiled weapons abounded, although in fact these “stockpiles” were not found to be as significant as initially believed. (Here it can be mentioned that the Oregon commune had an officially sanctioned police force that had been trained by the Oregon State Police Academy).

In addition, Brecher reported that he interviewed two mercenaries who claim they were offered a contract to assassinate Osho; one of the men claimed to have been employed as a hired hand by the CIA previously in covert ops in Central America. Both these men believed that the CIA was behind the assassination contracts. The men eventually bailed on the plan believing that it would have been certain suicide for them to attempt to kill Osho in a commune of thousands of zealous followers.(5)

Finally, several months after Rajneeshpuram had dissolved, the US Attorney for the district of Oregon at the time, Charles Turner, admitted that the government’s principle aim was to destroy the commune from the beginning. He admitted this in answer to a question as to why Osho had not be charged with any serious crimes, also stating that there was no evidence to link Osho to any of the serious crimes.(6) (Turner himself was the object of an assassination plot by Sheela and several of her assistants; the last of these was tried as recently as 2006).(7)

All of these facts are important to bear in mind because anyone with a casual knowledge of Rajneeshpuram tends to believe that the commune self-destructed owing to internal, internecine corruption, and that was all there was to it. But in truth the commune was from the beginning besieged with legal challenges and a hostile reception from locals, media, and state officials. However, the response of the commune, as led at that point by Sheela, was fierce and combative. There was no “Taoist approach” used, no yielding or practicing “no-resistance.” The approach was entirely contentious, “eye for an eye.” This approach was carried to ludicrous extremes, however.

2. The second major problem that faced the commune from the beginning had to do with Sheela’s psychological state and her questionable grasp of her master’s teachings. To what extent this all reflected on Osho is a separate issue and is discussed below. But for now, what can be safely said is that Sheela and her group of lieutenants—mostly all of whom were women—ran the commune with an iron fist, used their power in at times highly questionable ways, and showed little or no sign that they were involved in a personal spiritual practice (meditation, therapy groups, etc.).

Jill Franklin, who went by the name Satya Bharti when she was a close disciple of Osho and who had authored a couple of popular books on her master in the late 1970s, had this to say about the early days of the Oregon commune:

Even in the ranch’s first year there were more glimpses of ugliness than an intelligent person should have been willing to put up with.

That one sentence is really enough, but the rest of Franklin’s paragraph is insightful and important:

The handwriting was on the wall of every illegal building we erected and written into every letter of protest we sent off to local politicians accusing our adversaries of religious discrimination and bigotry. The us-and-them mentality that Sheela emphasized in mandatory general meetings and did her best to create by abrasive public behaviour fostered an atmosphere where it was easy to suspend critical judgment. Whatever our Bhagwan [Osho]-appointed leaders did was necessary, imperative. The community was struggling for its right to exist. In a battle against opponents who wanted us out of the state, the country—who saw us as red devils, Christ killers, communists, and menaces to the “American way of life,”—the community’s frequent skirting of the law and its dictatorial internal policies seemed justified in many ways despite a queasy feeling of distaste that never left me.(8)

Her point is well stated. The “feeling of distaste” speaks volumes and is testimony to the fact that Franklin never lost her sensitivity, was never completely taken over by Sheela’s powerful personality and compelling agenda. The same cannot be said for many others. Sheela may not have won any popularity contests, but her authority was so unquestioned by most that many in fact became very devoted to her. Not in the way they were devoted to Osho, but in the way a child can become attached to a parent who may not be all that likeable but who is, nonetheless, present in the child’s life, and in Sheela’s case, far more present than the other “parent” who was spending all his time in silence in his room. Consistent with classic family dynamics Sheela became the dominant parent primarily because she was forcefully there.

Connected to all this is a controversial topic, the issue of Osho’s feminism. It is no secret that Osho had a highly developed feminine element in him—his appreciation of beauty in form, his masterful understanding of relationship, his body-centered spirituality, his elegant manner of expression, his trenchant condemnations of patriarchal power structures in politics and religion, and so on. As if to confirm all this he installed women into most of the administrative power posts in his communes. Sheela herself was famous for in turn assigning only women as her aids. The men around her, whether they were assistants or friends, were mostly gay men. There were no edgy Bodhidharma-types in her immediate realm, to put it mildly.

I was once listening to a talk given by an old Native Indian shaman named Sun Bear. In this talk he made the comment about how risky it can be to give exclusive power to women in a communal spiritual setting. He said that because of the centuries of oppression and marginalization of women, when they finally get power they cannot resist using it to its maximum, and commonly abusing it as well. Sun Bear himself was a traditional patriarch, but in the case of Sheela and the Oregon commune there is a point in there that Osho essentially agreed with. He remarked in one of the press interviews shortly after Sheela left the Oregon commune in September 1985:

Just one woman cannot destroy my respect for womanhood. I will go on giving chances again and again, for the simple reason: for thousands of years women have not been given chance. So it is possible that when they get the chance—it is just like a hungry man who has been hungry for many days is bound to eat too much and is bound to become sick by eating. That’s what happened to Sheela: she had never seen so big money, she had never seen so much power, in my name she had ten thousand people who could have died or done anything

Sheela had no spiritual aspirations. Seeing that she has no potential, at least in this life...and this was my impression on the very first day she entered my room in 1970—that she was utterly materialistic, but very practical, very pragmatic, strong-willed, could be used in the beginning days of the commune...because the people who are spiritually-oriented are stargazers.(9)

Later, in a series of talks he gave in September of 1988 on Zen, he remarked,

The first commune was destroyed because of women’s jealousies. They were fighting continuously. The second commune [the Oregon commune] was destroyed because of women’s jealousies. And this is the third commune--and the last, because I am getting tired...Still, I am a stubborn person. After two communes, immense effort wasted, I have started a third commune, but I have not created any difference—women are still running it.(10)

The point here is obviously not to suggest that women cannot run organizations, but rather to highlight the area of the Oregon commune’s relationship with the surrounding aggressive masculine energies embodied in the form of its many political enemies. If the commune was being run by someone psychologically unhealed with the masculine polarity (as Osho explicitly and implicitly suggested about Sheela) then that could potentially show up in the form of an unskilled approach that would backfire (which is what happened).

Given the facts, it can be reasonably concluded that Sheela did not demonstrate a balanced or valid expression of Osho’s teachings and overall philosophy, because she lacked an introspective disposition—uninterested in meditation and having, quite literally, slept through her master’s teachings. To top all that off she was too young, being thrust into a high-powered position during the relatively green time of her early thirties. She lacked the life experience and consciousness needed to deal with all the complex issues coming at her at once.

Given the facts, it can be reasonably concluded that Sheela did not demonstrate a balanced or valid expression of Osho’s teachings and overall philosophy, because she lacked an introspective disposition—uninterested in meditation and having, quite literally, slept through her master’s teachings. To top all that off she was too young, being thrust into a high-powered position during the relatively green time of her early thirties. She lacked the life experience and consciousness needed to deal with all the complex issues coming at her at once.

None of that is to imply that the Oregon commune would not have been destroyed had Sheela not been running it. It may have even if it had been run by a wise secretary who had been strong, non-defensive, and unthreatened by surrounding hostility. There is no way to know for sure. But it can be comfortably concluded that Sheela’s disposition aided in and hastened the downfall of the commune.

3. The third major problem, in addition to the public and official perception of Osho and his disciples and Sheela’s questionable level of development and understanding of Osho’s vision, was ultimately the most serious. It was that a conflict was brewing from within the community itself between two key factions. The first of these was grouped around Sheela, a loyal band of about a dozen lieutenants (mostly women, dubbed the “temple Moms”), all of whom had great power in the commune, in large part owing to Osho’s self-imposed silence. During the time of his withdrawal Sheela had assumed (in effect) dictatorial powers. Because Osho had emphasized the importance of “surrender” the orders of Sheela and her assistants were rarely questioned and almost never rebelled against, because it was assumed that to rebel against Sheela was to rebel against Osho, which would defeat the whole purpose of being there in the first place. Osho had gone to pains to distinguish surrender from blind obedience—the idea was to surrender the controlling tendencies of one’s ego, but not to blindly obey any so-called authority—however this difference proved to be insufficiently grasped as events would show.

The second faction was that of the “Lao Tzu residents,” the group of caretaker disciples who lived closest to the master, in his residential complex called Lao Tzu House. These were basically his companion caretaker Vivek, his doctor Devaraj, his dentist Devageet, his cook Nirgun, his book editor Maneesha, and one or two others. These disciples were not involved in the administrative running of the commune, so they lacked secular power in the organization, but they had tremendous status nonetheless simply by virtue of their proximity to Osho.

The entire experiment around Osho—especially from approximately 1970 in Mumbai up till the dissolution of the Oregon commune in 1985—was essentially a type of bhakti yoga, that is, a devotional path based on a deep personal connection with one guru, what Osho often referred to as a “love affair with the master.” Although psychotherapy groups and meditation practice were essential elements within the organization, the whole thing was truly held together by each disciple’s “connection” to Osho. The idea behind this type of devotionalism is for it to become a means of deepening one’s attunement with one’s own higher nature, using the objectification of that higher nature—in the form of the divine, and in the case of a living guru, in the form of the guru himself—as a type of proxy link. However inevitably in the course of such “linking” the disciple develops very strong personal feelings for the guru, even at times forgetting that the whole thing is supposed to be a means by which to access a vaster and more profound level of impersonal love for all.

The entire experiment around Osho—especially from approximately 1970 in Mumbai up till the dissolution of the Oregon commune in 1985—was essentially a type of bhakti yoga, that is, a devotional path based on a deep personal connection with one guru, what Osho often referred to as a “love affair with the master.” Although psychotherapy groups and meditation practice were essential elements within the organization, the whole thing was truly held together by each disciple’s “connection” to Osho. The idea behind this type of devotionalism is for it to become a means of deepening one’s attunement with one’s own higher nature, using the objectification of that higher nature—in the form of the divine, and in the case of a living guru, in the form of the guru himself—as a type of proxy link. However inevitably in the course of such “linking” the disciple develops very strong personal feelings for the guru, even at times forgetting that the whole thing is supposed to be a means by which to access a vaster and more profound level of impersonal love for all.

What appears to have happened in the case of Sheela and the Lao Tzu House residents was a fascinating drama that seemed straight out of William Golding’s Lord of the Flies.(11) It became a textbook case of corrupted bhakti yoga, with Sheela developing powerful projections on her master and the “family structure” around him. That is, she personalized the whole thing to such a degree that it became a dangerous situation precisely because of the power that had been invested in her. She began to resent those who were closest to Osho and in a spectacular example of amplified projection she began to perceive these people as actually dangerous to both Osho and to her own power base. She then followed this seeming logic like the relentless soldier that she was and accordingly plotted to have them eliminated. In her world it all seemed to make sense. And in a vivid demonstration of the problems inherent in dictatorship those closest to her immediately bought into her perceptions, and as a result began to share the same or similar perceptions—the prime one being that Osho’s closest caretakers were dangerous and had to be got rid of.

There has never been the slightest evidence that Osho’s caretaker disciples were in any way a threat, either to him or to the secular regime of the commune as led by Sheela; however, it has been made clear that there was a significant psychological rift between the two factions. More than one source reported that Osho’s doctor, Devaraj, the man who became the target of an actual assassination attempt, was “not on speaking terms” with Sheela and her associates and had not been for some time. Sheela was known to have “hated” this faction since the days of the first India commune in Poona. However, what seems clear is that this animosity was motivated primarily by jealousy. “Sam,” the pen name of the author of Life of Osho, argues that the contrary was also true, that is, that some or all of the Lao Tzu residents were also jealous of Sheela.

What was going on with Sheela? Why did she play the part she did in the disaster which followed? From the first the pressure on her must have been enormous. And the workload of running the Ranch was only the beginning of it—for Sheela had to moonlight as an ogress. In this strange scenario of Osho for and against his own religion Sheela was at the epicentre of all the contradictions. Sheela did it, they were all to say; Osho didn’t know anything about it, it was all Sheela’s fault. Making sense of her behaviour is made even more difficult by the fact the main accounts of the Ranch were written by, or heavily influenced by, the accounts of the small group of sannyasins who lived in Osho’s house—and there’s a sense of jealousy of Sheela you can cut with a knife coming off all of them.(12)

It’s interesting to contrast Sam’s observations of Sheela with those of Rosemary Hamilton (Osho’s cook), following a rainstorm and flood that caused damage during the early days of building the Oregon commune:

One vivid picture of that flood stays with me. Sheela crossing the swollen river to keep her daily appointment with Bhagwan (Osho). Dark eyes blazing, long black hair streaming in the cold rain and wind, she forced a terrified, snorting black stallion through the yellow surging water—matching his brute power with her own, and winning. It was my first clear glimpse of why Sheela had been chosen to carve a city out of a wilderness.(13)

That Sheela was deeply attached to her master is not in question, and so the likelihood that she was not able to overcome her jealousy of those who were close to him is also a given. But the idea that others were jealous of Sheela probably has some truth to it as well. She was for several years the only one who had daily access to him, and who was his representative and spokesperson to the world. She was a chosen one, a golden girl, and such special status alone must have earned her at least envy in the eyes of many. Another passage from Rosemary Hamilton throws light on this, following her being appointed to the position of a cleaner in Osho’s house:

I watch my ego rise and preen itself as I come in through the gate as a cleaner: the rush of pride as the guard studied the list and nodded me through; the greater thrill when he no longer looked at the list; the envious stares of sannyasins who witnessed my easy coming and going through the sacred portal.(14)

It has long been a tradition in spiritual communities that serving one’s teacher is a great honour, and in more devotionally oriented fellowships—which Osho’s certainly was—to be near the guru is considered to be the highest blessing and one of the best possible opportunities to develop rapidly on a spiritual level. Accordingly, it is also a position prone to competition and jealousy.

Osho and Sheela: The Magician and his Dangerous Daughter

A few key points stand out in any attempt to objectively analyze the matter of Rajneeshpuram and Sheela. First, Osho’s self-imposed three-and-a-half-year silence was obviously pivotal, and while it cannot be said to have been the prime causal force—after all, Sheela may still have engineered all that happened even if Osho had been giving daily lectures—it was unquestionably a powerful contributing factor.

Secondly and more importantly, in assessing all this from the point of view of psychodynamics, we are inevitably faced with the need to address the issue of what, if any, level of accountability Osho had in Sheela’s actions. There have been, naturally, widely diverging views on this. At one pole—represented by Osho-loyalists like Juliet Forman (aka Maneesha, Osho’s chief chronicler) and George Meredith (aka Devaraj, aka Amrito, his doctor)—are those who see Sheela as a discrete entity who acted entirely on her own devices and whose criminal acts were in no way influenced by Osho’s ideals or in any way a product of his vision or temperament. At the other pole are disgruntled ex-followers like High Milne or Christopher Calder, the latter of whom claims he was Osho’s second Western disciple, and who goes so far as to describe the entire series of criminal events that befell the Oregon commune as having been fully orchestrated by Osho, implying that Sheela was nothing, but a passive puppet manipulated by her guru’s heavy hand.

Secondly and more importantly, in assessing all this from the point of view of psychodynamics, we are inevitably faced with the need to address the issue of what, if any, level of accountability Osho had in Sheela’s actions. There have been, naturally, widely diverging views on this. At one pole—represented by Osho-loyalists like Juliet Forman (aka Maneesha, Osho’s chief chronicler) and George Meredith (aka Devaraj, aka Amrito, his doctor)—are those who see Sheela as a discrete entity who acted entirely on her own devices and whose criminal acts were in no way influenced by Osho’s ideals or in any way a product of his vision or temperament. At the other pole are disgruntled ex-followers like High Milne or Christopher Calder, the latter of whom claims he was Osho’s second Western disciple, and who goes so far as to describe the entire series of criminal events that befell the Oregon commune as having been fully orchestrated by Osho, implying that Sheela was nothing, but a passive puppet manipulated by her guru’s heavy hand.

An example of Calder’s view is as follows:

In an attempt to subvert a local Wasco County election, Rajneesh [Osho] had his sannyasins bus in almost 2,000 homeless people from major American cities in an effort to unfairly rig the voting process in his favour. Some of the new voters were mentally ill and were given beer laced with drugs to keep them manageable. Credible allegations have been made that one or more of the imported street people died due to overdosing on the beer and drug mixture, their bodies buried in the desert. To my knowledge that charge has not been conclusively proven. Rajneesh’s voting fraud scheme failed, and the derelicts and mental patients were returned to the streets after the election was over, used and then abandoned.(15)

That these homeless people were there and were fed and clothed (not to mention 'cigaretted') I can confirm, as I worked, ate, and smoked alongside some of them myself, however it is regarded as common knowledge among most who have seriously studied the facts that this scheme was thought up and enacted by Sheela and her aids. Most agree that Osho green-lighted it, but it was a classic Sheela initiative.16 Despite that nowhere in Calder’s above paragraph (or in similar paragraphs in the article) does he even mention Sheela’s name.

A bit more background information about Sheela is helpful at this point. She was born Ambalel Patel Sheela, in Baroda, India, in 1949. She became Osho’s disciple in her early twenties. As is often noted one who becomes a devoted follower at a very young age of an older, powerfully charismatic figure runs certain risks, because their ego-structure has not been firmed up yet by sufficient life experience. Being young they are more trusting and open, and lack comparative reference points. Accordingly, the guru can easily become the dominant center of their universe. I recall back in the early 1980s talking to a fellow disciple of Osho, a young woman of around twenty-five. In the course of chatting with her about discipleship I spontaneously blurted out, “well, you’re not going to be with Bhagwan (Osho) for your whole life.” She looked deeply indignant, as if I’d just gravely insulted her (which in a sense, I unwittingly had), but also looked at me with sympathy as if I was some kind of fool. She retorted, “I am going to be with Bhagwan my whole life.” She said this with all the conviction of youth, as certain as the Sun rising tomorrow.

As a disciple Sheela was noteworthy for a few things, one of which was an exceptionally strong personal energy, and the other was a strange habit of sleeping through her master’s morning lectures. This latter fact is attested to in some surviving photos of the time: Osho lecturing on the podium, dressed in his simple white robe that in those days (the 1970s) he always wore, and before him, several hundred orange-robed disciples, all sitting, either listening attentively, or eyes closed in meditation. And there, among all of that, was an Indian woman in the front row lying on her side—snoozing.

Osho was known to have accepted Sheela’s slumbering, even claiming on one occasion that while she slept he “worked on her” (an expression he often used to indicate ways in which he would influence disciples on subtle levels—though he stopped using this expression toward the end of his life). But in hindsight the strangeness of this habit of hers can be seen to be an interesting metaphor for her later fall from grace—the disciple who literally slept through her master’s daily teachings on how to be awake. The irony is thick. And when seen in light of Sheela’s remarkably flagrant violations of common sense and conventional laws during the fiasco of the Oregon commune collapse, the whole thing is all the more suspect.

By “suspect” I don’t imply anything conspiratorial, such as interpretations that Sheela was Osho’s denied shadow element, the part of him that unconsciously wished to sabotage his own work, or related psychological sophistries. What seems clear rather is that Sheela was simply much like Osho in certain key ways—most noteworthy being her rebelliousness and need to cut a unique figure, to answer to nothing but her own highest call, and to steamroll anything that would get in the way of that.

It is useful to pause for a moment here and enter left stage Chogyam Trungpa, the brilliant and highly controversial Tibetan Buddhist master. In the late 1970s Trungpa, breaking with tradition, had appointed a Westerner—his close student Thomas Rich—to be his “Vajra Regent.” This was to be the man who would carry on with the vision of his teachings and community after he died. This of course is widely known to have ended in disaster. Not long after Trungpa passed away in 1987 due to liver damage incurred by alcoholism, Osel Tendzin (Rich’s given Tibetan name) revealed that not only did he himself have AIDS, but that he’d slept with several of his students and knowingly infected at least one of them. The scandal rocked Trungpa’s community and cost it a number of members, although it did survive (Tendzin himself succumbed to AIDS-related complications in 1990). But what is of interest here is to note the common patterns, much as how they transmit, from generation to generation, through a typical family. As Lawrence Sutin in his excellent history of Buddhism All Is Change, observed:

There is a discomfiting parallel between Tendzin’s blatant denial as to sexual choices and the attitude of Trungpa toward his own constant drinking.(17)

Sutin’s insight is glaringly obvious, and yet is the kind of observation that can be remarkably hard to make for those too close to such situations. Alcoholics are famous for their capacity to demonstrate denial, and those close to alcoholics (or other types of abusers/misusers) are equally famous for their capacity to enable, to develop thoroughly myopic vision in one eye. When all this is added into a spiritual mix the result can be particularly strange, because for those deeply committed to spiritual teachings the need to believe that they (and what they are involved in) is truly special, beyond the pale, exempt from the laws of the universe, can be so pervasive that it overcomes common sense. Osel Tendzin himself admitted that the reason he went ahead and slept with the people he did, even knowing he had AIDS, was precisely the belief that he, and what he was involved in, was truly special:

I was fooling myself…thinking I had some extraordinary means of protection…(18)

And moreover, that it was his guru who had assured him that no wrong could come to him, as Stephen Butterfield recounts in his book The Double Mirror:

Tendzin had asked Trungpa what he should do if students wanted to have sex with him, and Trungpa’s reply was that as long as he did his Vajrayana purification practices, it did not matter, because they would not get the disease.(19)

The main point here is not to highlight Osel Tendzin’s or Chogyam Trungpa’s character flaws, serious as they may have been, but rather to see that Tendzin was, in certain important ways, a reflection of his master. In the case of Osho and Sheela, the parallel is fairly straightforward. There are too many traits in her that are easily recognized in Osho’s well documented character (mostly documented by himself) not to see their similarities. During Osho’s three-plus years of silence Sheela was given enormous power and ran the Oregon commune essentially as a dictator. During that time, she began to see herself as both a queen and a pope, and even dressed the part, decking herself out in red robes, and wearing her mala (the 108 beads with Osho’s photo attached to a locket) with white pearls, wrapped around her head like some sort of garish Tantric mitre—the pistol-packing pontiff herself.

The whole thing is absurd in retrospect, knowing now that she literally dozed through her master’s teachings, never meditated, never underwent therapy, and never showed real interest in esoteric spiritual ideas. What, then, was she even doing there? Clearly, she was infatuated with her guru, but equally clearly, she soon grew to become even more infatuated with her role. In the aftermath of the revelation of the criminal activities enacted by her and her confederates (attempted murder, an outrageous bio-terror attack, wiretapping, etc.), Osho’s main argument was that he was not responsible for the actions of others. His funniest line was probably “enlightenment means that I know myself—it does not mean that I know my bedroom is bugged.”

That may be so, and Osho’s attempt to humanize enlightenment can only be appreciated, but the fact remains that he appointed a woman with the character traits that she had to an extraordinarily sensitive and important position in his organization. Why? The only reasonable answer is that he did so unintentionally, and unwittingly, precisely because Sheela was, at the deepest level, too close to him for him to see who she really was, and what she was really capable of. By “close to him” is not meant a real intimacy, because she did not approach anything like a “friend” to him. Rather she was, to a certain degree, a reflection of him in disposition. Despite the fact that she was nowhere near his intellectual equal, and had nothing like his spiritual zeal for transcendental consciousness—in short, comparatively speaking he was awake, she was not—she was nevertheless a close pattern-match with him on the level of certain character traits, perhaps most notably being a strong attachment to being right about things and a level of stubbornness connected to that, that goes far beyond being merely endearing.

In July of 1985, shortly before the commune fiasco erupted, Osho, while speaking about Sheela, was quoted in The Sunday Oregonian as saying,

Look at her. She is so beautiful. Do you think that anything more is needed? She can manage this whole commune. I have sharpened her like a sword. I have told her to go and cut off as many heads as she can.(20)

The last sentence in particular appears to confirm the view that Sheela was in many ways an echo of her master on the level of character. Osho without question “cut off heads” in his many years of fiery discourse. Sheela was, in her way, trying to do the same—she was just infinitely clumsier.

Anyone who has ever listened to Osho talk about his past will, if they listen closely, free of sentimental attachment to his obvious grace, be struck by a few things. First and foremost is Osho’s tendency to portray conflicts between himself and others in such a light that always, without fail, demonstrates Osho’s righteousness. Time and again we hear stories of him encountering someone, calling them out on something, and they sooner or later admitting that Osho is right. He seems to have been the only man in history who never lost an argument, was never wrong, or was never put in his place by anyone. He always, without fail, is on the giving end of such encounters. It’s conceivable that that may have simply been the truth. Undeniably he was a brilliant man, and equally undeniably, he was very contentious. In the area of spiritual one-upmanship, he probably only had one modern-time equal, the cranky anti-guru guru U.G. Krishnamurti (not to be confused with his other, more famous rival, J. Krishnamurti), with whom Osho once engaged in an amusing war of words with—U.G. calling Osho a “pimp,” and Osho returning the volley by declaring U.G. a “phony guru.” Osho seemed always to have been at war with something or someone. He even famously exchanged hostile letters with Mother Theresa, calling her an “idiot” and “hypocrite” for—in his Nietzschean-like estimation—“weakening” people by seducing them into the Church, and she returning the favour by insinuating that he was bound for hell and that accordingly, she would pray for him. To which he (justifiably, it must be said) responded, “Who has given you permission to pray for me?”

I have personally been involved with several spiritual organizations and communities in addition to Osho’s and I can confidently state that sannyasins (the name for Osho’s disciples), while they could be amongst the most passionate, alive, intelligent, and affectionate—were often as well (particularly in the ‘80s) among the most abrasive and unfriendly. Osho valued authenticity very highly and was contemptuous of “English civility”—in a word, niceness—probably more than anything. Back in the heyday of the encounter-type groups of the 1960s-80s, the intention to “become real,” coupled with the “me”-emphasis of the Baby Boomer generation, gave rise to the prioritizing of authentic behaviour. This could definitely yield a startling openness and aliveness but just as often could amount to simple unkindness in the name of “being real.” It has been argued that Osho’s community was not warmly welcomed by Oregonians in the early days (1981) of the commune, and while that is unquestionably true, what is less commonly mentioned is that the general demeanor of Osho’s disciples was often itself anything but warm and inviting. Some of that was an echo of Sheela’s character and leadership style, but some of it was also the natural outgrowth of Osho’s teachings on the importance of exalting the self above all else.

Osho was fighting his whole life—through his college years (which included expulsions), with professors, with religious leaders, even with other avant-garde gurus. That he handpicked Sheela, also a pitbull, for such a pivotal position can hardly be surprising. And thus, it stands to reason that he bears some degree of culpability in Sheela’s criminal acts, even if only indirectly, and even if only psychologically. She was his devotee—in the language of psychological alchemy, a Moon reflecting the light of her Sun. His decision to retreat into silence for over three years and allow a young woman in her early thirties to assume command over such a vast and sprawling fellowship with millions of dollars to play with, could only have occurred if he saw in her some quality that reminded him enough of something within himself—even if he was ultimately unaware of her more destructive potentials.

In September of 1985 shortly after Sheela and some of her lieutenants had fled the U.S., Osho appeared before the press in a series of somewhat strange interviews designed to flush everything out in the open. There, in a question about why he chose an intelligent but “mean-spirited” woman to be his chief representative, he revealed his thoughts about Sheela, claiming that she had been a necessary evil:

I could not put the commune in the hands of some innocent people—the politicians would have destroyed it…looking at the world, whatever happened, although it was not good, only bad people could have managed it. Good people could not.(21)

In a discourse a few days later Osho claimed that he put Sheela in a position of power knowingly, declaring,

I had chosen Sheela to be my secretary to give you a little taste of what fascism means. Now live my way. Be responsible, so that there is no need for anybody to dictate to you.(22)

In light of all that happened this last comment of Osho’s is dubious. If he knowingly chose Sheela to be in a position merely as some sort of elaborate device to give his disciples a lesson, then he did so knowing full well the potential dangers. That people were poisoned, and that some nearly died, underscores that point. It is rather more likely that Osho’s remark was that element of his character structure (referred to before) surfacing—that being the need to reframe everything in such a way as to cast himself in the best possible light. “Best possible light” in this sense refers to the crucial quality of psychological knowingness. As a master of wisdom Osho must above all be seen to be wise, knowing. Innocent he can be seen to be of more worldly matters but not of the deeper psychological issues. Without manifest wisdom in that area his function as a fully enlightened master gets thrown too uncomfortably into question.

That Osho had tremendous wisdom and insight is obvious—and that he bore a critically important message and teaching for 20th century humanity is not in question. One has merely to read any one of his over six hundred books in print, or even to watch one of his many videos, to see that. Rather what is being highlighted here is his need to be seen as essentially infallible. The irony is that Osho regularly scorned the pretentious priesthoods and religious leaders of history for, in one form or another, presenting their infallibility to a duped public. And yet he himself appeared to do the same. I am unaware of any public declaration by Osho that his appointing of Sheela as his de-facto prime minister was simply a mistake on his part.

Finally, it should be noted that Sheela herself, after over twenty years of seclusion, surfaced in the public eye again. A series of videoed talks given by her were downloaded to YouTube in 2007. In these talks her manner of speaking is peculiar, with mannerisms oddly reminiscent of her master, as she presents her case and tries to promote her essential innocence. Judging by the viewer’s comments attached to these videos she has been unable to shake the general perception of the public that she and she alone, was responsible for the Rajneeshpuram Orwellian nightmare.

But the fact that she royally erred does not automatically exonerate Osho. She was not just his spiritual child, she was also his brainchild. He created the program, the vision, the view, the raison d’etre of his communes. It could not have been otherwise. Much as Judas must have been a close affiliate of Jesus, his betrayal, witting or unwitting, orchestrated or un-orchestrated, reflects at some level the rebelliousness of his master, even if that rebelliousness is of a far more immature quality.

The Jesus-Judas myth applies well enough to Osho-Sheela. In the end Osho’s essential argument that everyone is responsible for themselves is clearly true, but what is also true is that an initiative like Osho’s sannyas has enormous impact and equally enormous consequences. Osho, though a man far ahead of his time, was still a man, and capable only of judgment that would reflect his understanding, his view, his characteristics. My main argument here is that his very nature and his very vision drew to him a certain type of seeker, one that inevitably would cause trouble.

The typical way of seeing such a thing is that Osho was not responsible for who Sheela was, but partly responsible for what she did. I see it differently. He was not responsible for her actions but he was, naturally, responsible for who he was, and thus, by extension, responsible for attracting to him a person with Sheela’s qualities. And because of who she was, he gave her too much power, like a father giving the keys of his very fast and dangerous car to a favourite daughter who is not yet of driving age. And, to extend the metaphor—which also happens to be literal in this case—he did this because he himself also drove maniacally. That he did it with more skill than his “daughter” is a secondary point.

Concluding Remarks

Gurdjieff, a master well acquainted with the traps of communal life based on higher ideals, once stated,

It is no part of the master’s role to take over the disciple’s effort of understanding; the latter, and he alone, must make it for himself. The shocks, suggestions and situations calculated to provoke the disciple’s awakening are there solely to prepare and train him to do without the master, to go forth under his own steam as soon as he shows himself capable of doing so.(23)

It is no part of the master’s role to take over the disciple’s effort of understanding; the latter, and he alone, must make it for himself. The shocks, suggestions and situations calculated to provoke the disciple’s awakening are there solely to prepare and train him to do without the master, to go forth under his own steam as soon as he shows himself capable of doing so.(23)

No better defence of Osho could be provided than Gurdjieff’s words. But the problem with Rajneeshpuram was that Osho’s prolonged withdrawal and Sheela’s dominant reign began to confuse the issue as to who actually was the master. Osho may have been ultimately interested in the disciple’s “freedom,” but clearly Sheela was not. She was interested primarily in the survival of the commune at all costs and, needless to say, in the consolidation of her own power base. In that position she did in effect attempt to “take over the disciple’s effort of understanding.” Once the basic principle stated in Gurdjieff’s quote is violated, a mystery school enters the grey area between spiritual training ground and cultic organization—or, in worst case scenario, a “fascist concentration camp” as Osho himself put it.

One view of the matter has it that Osho himself was never truly happy in Oregon and that his withdrawal from public speaking, which had been his main and only substantial form of communication with his people for so many years, was actually a manifestation of a type of depression. But the very idea that he could be “depressed” was absurd, sacrilegious to the many who followed him and believed wholesale in the idea that he was a fully realized being. But was he?

Back in the late 1980s I read a book by the Canadian psychotherapist and one-time Osho disciple Robert Masters, titled The Way of the Lover. Masters had been present at the original Poona ashram in the ‘70s, and he had contrasted Osho’s appearance in the ‘80s at Rajneeshpuram unfavourably with his bearing in the ‘70s. “Bhagwan’s face had lost its balance and luminosity, his eyes lost their timelessness and depth” he wrote, adding that Osho “looked drugged, and appeared to be oblivious to it all.”(24)

At the time I had dismissed Masters’ remarks as those common of a disaffected disciple, especially one who had gone on to set himself up as a teacher and acquire his own following (as Masters had done in the ‘80s). Now, two decades later, I think he was correct, at least to some degree. There is no question that in many of the Rajneeshpuram videos Osho does not look like the blissful man he claimed to be. At times he looks tired, even uninspired, and—if I dare say—lonely. And how could he not be? This was a man with no peer, no real friends, no one with whom he could encounter his own self. Of course, in theory full enlightenment eliminates the need for all that. After all, if you are one with everything, what need is there for a peer? Or for anyone at all? The question, then, hinges on the depth of Osho’s self-realization. If it was not complete, then human needs remained, and if those needs were not met, then there would be unhappiness. The fact that Osho used nitrous oxide apparently for entertainment purposes (see Chapter 12) even if only occasionally, suggests that he was not completely content.

Content or not, one thing that is clear is that a fundamental idea was mistakenly applied at the commune. That idea was, essentially, Crowley’s chief law of Thelema—“Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.” Many, if not most, of Osho’s disciples had likely never heard of Crowley, but his teachings, as modified from Francois Rabelais’s original ideas published in his Gargantua and Pantagruel in the 16th century, were highly evident in many of Osho’s core ideas, and reached a distorted and incorrect expression in the very personality of Sheela herself.

Crowley’s “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law” follows no law but that of honouring the true self, aligning wholly and individually with one’s highest truth, and not allowing anyone—or more to the point, one’s own ego—to deprive oneself of that truth. This was essentially what Osho taught as well. However, it is an idea that is extraordinarily susceptible to being co-opted by the ego for its own agendas.

Sheela was a superb expression of antinomianism or “spiritual lawlessness”—she was a true spiritual outlaw and refused to allow anyone to “mess” with her will. That part she got right. The only problem was she failed to find her True Will. She thus enacted a corrupted version of Crowley’s Thelemic law, the ego’s version of the True Will. This inevitably ends in disaster because it does not take into account karmic cause and effect. The True Will does not harm, but the same cannot be said for the ego’s version, which simply tramples whatever is in the way. Sooner or later it meets something it cannot trample and is destroyed by the echo of its own reckless aggression.

Sheela made serious errors and committed serious crimes. Osho’s error was in putting her in that position in the first place. But something in his nature allowed for all this to happen.

Finally, there is the “bird’s eye” view of things. As mentioned in the previous chapter, Gurdjieff proclaimed that his serious car accident in 1924 was not actually an example of what he called the Law of Accident, but rather was a manifestation of a type of negative force that opposes the arising of consciousness in the world—a force that he called Tzvarnoharno. One of Gurdjieff’s basic ideas is that the universe works by a means of checks and balances, like an organic body, and has a self-regulated equilibrium. If anything disturbs that balance it is opposed, something like how bacteria or viruses in the body will be attacked by antibodies or white blood cells.