G. I. Gurdjieff: The Black Devil of Ashkhabad

The following appears as Chapter 2 of my book 'The Three Dangerous Magi' (Axis Mundi Books, 2010).

The following appears as Chapter 2 of my book 'The Three Dangerous Magi' (Axis Mundi Books, 2010).

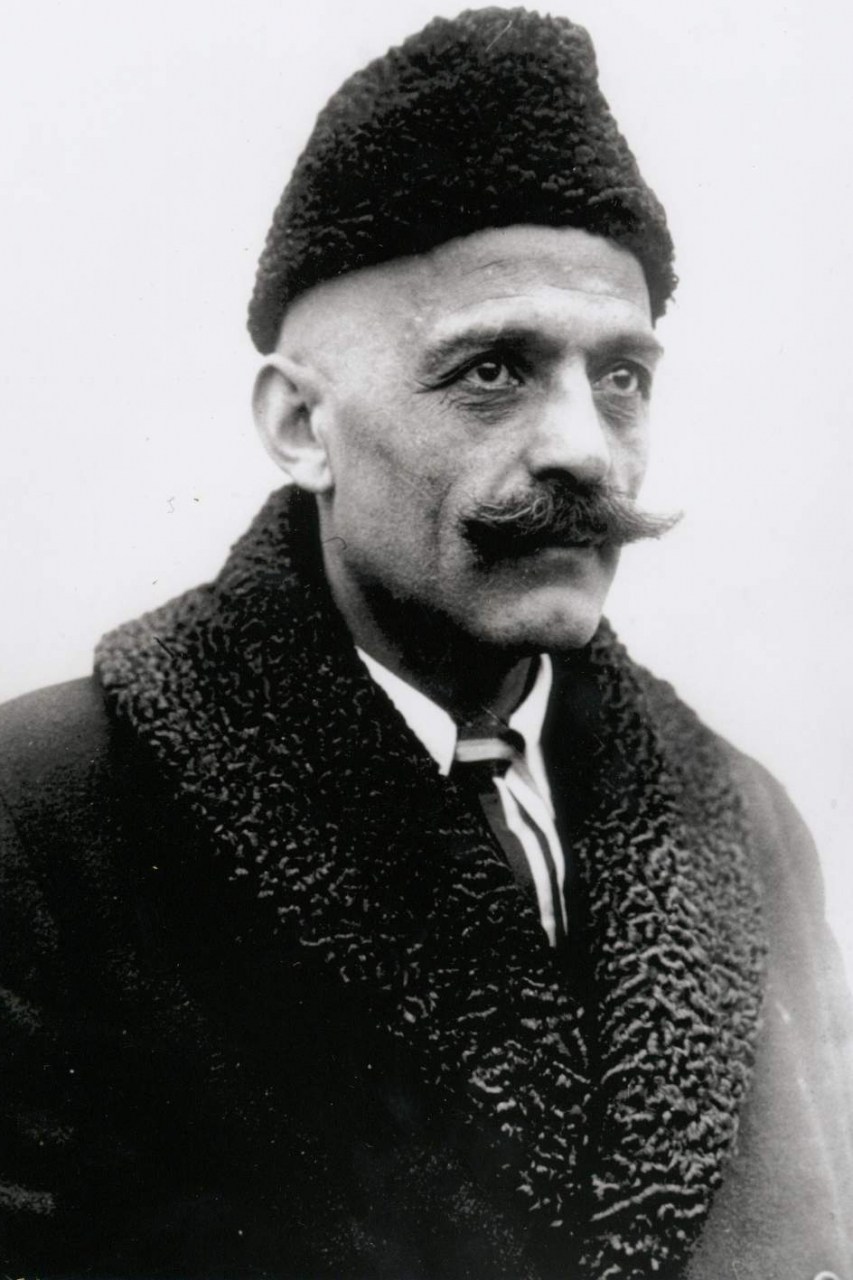

Till Gurdjieff raised up his head, one could think he is only a great scientist, or something like that. But when he looks at you, you can no more see his face, neither know if he has great or little eyes; you see only two immense wells of black light.

—Rene Daumal

Gurdjieff exercises on those who go to him a kind of grip of a psychic order which is quite astonishing and from which few have the strength to escape.

—Rene Guenon

Gurdjieff is a kind of walking god…a planetary or even solar god.

—A.R. Orage

Back around the year 2000 I received a mysterious phone call from a man in California who said he’d looked at a website of mine at the time, in particular an article that I’d written about Gurdjieff, and that he had some questions. While he wasn’t exactly breathing heavily into the phone or using a voice modifier he was rather evasive about his identity, preferring to tell me only that he’d been part of a group for a long time that had been on a mission to locate the Sarmoung Brotherhood (the mysterious Central Asian organization that Gurdjieff claimed to have been an initiate of). He said they’d organized journeys, and during a rare lull between Afghan wars they followed some tips and traveled to the Khyber Pass region. As is usually the case with such stories he said the “trail went cold” while in northern Afghanistan. I half-heartedly wondered to myself whether he’d bothered to consult Fielding’s Guide to the World’s Most Dangerous Places before setting off to the land of poppies and burkhas. Doubt as I might, however, he sounded legitimate and sincere—and no longer young—and he really wanted to know what I thought about the Sarmoung legend.

I told him about my own

wanderings in that part of the world years before, particularly through Kashmir and up into Ladakh where I’d stayed for a while

in a Tibetan monastery. I’d had a series of exotic and interesting experiences

but I did not find any “Sarmoung Brotherhood” either. In the end I’d concluded

that the value of the Sarmoung myth was very similar to the Tibetan idea of

Shambhala (or Shangri-la)—that is, it was primarily allegorical—and perhaps

might even be sourcing from the same story. This was tantalizingly hinted at by

William Patrick Patterson in his book Eating

the “I” in which Patterson (then a student of Lord John Pentland, himself a

direct disciple of Gurdjieff) recounts his meeting with the radical Tibetan

Buddhist master Chogyam Trungpa in the early 1970s. Trungpa, who had fled Tibet in the 1960s, had been raised as the

incarnate abbot of a group of monasteries in eastern Tibet known as “Surmang.” Patterson

noted the close similarity of the terms Sarmoung and Surmang—something made all

the more interesting by the fact that Gurdjieff actually did claim that he

spent a couple of years in Tibet around the period 1900-1903, studying their

traditions, picking up some of the language, and even, he claimed, taking a

Tibetan wife.1

I told him about my own

wanderings in that part of the world years before, particularly through Kashmir and up into Ladakh where I’d stayed for a while

in a Tibetan monastery. I’d had a series of exotic and interesting experiences

but I did not find any “Sarmoung Brotherhood” either. In the end I’d concluded

that the value of the Sarmoung myth was very similar to the Tibetan idea of

Shambhala (or Shangri-la)—that is, it was primarily allegorical—and perhaps

might even be sourcing from the same story. This was tantalizingly hinted at by

William Patrick Patterson in his book Eating

the “I” in which Patterson (then a student of Lord John Pentland, himself a

direct disciple of Gurdjieff) recounts his meeting with the radical Tibetan

Buddhist master Chogyam Trungpa in the early 1970s. Trungpa, who had fled Tibet in the 1960s, had been raised as the

incarnate abbot of a group of monasteries in eastern Tibet known as “Surmang.” Patterson

noted the close similarity of the terms Sarmoung and Surmang—something made all

the more interesting by the fact that Gurdjieff actually did claim that he

spent a couple of years in Tibet around the period 1900-1903, studying their

traditions, picking up some of the language, and even, he claimed, taking a

Tibetan wife.1

As with so much of Gurdjieff’s story allegory blends easily with fact, as does fiction with teaching. Like Crowley, he was a man extraordinarily difficult to pin down, one given to changing on a moment’s notice depending entirely upon which angle you were viewing him.

My familiarity with Gurdjieff went back further than the time of my phone call from the intrepid Californian. Sometime back around 1980 while living in Montreal the janitor of my apartment building had me up to his room for tea one evening. While falling into a rather intense conversation with him and his girlfriend about altered states of consciousness and related matters, he asked me whether I’d heard of Peter Ouspensky, a Russian journalist who lived in the first half of the 20th century. I had, but only vaguely. I’d remembered his mention in Colin Wilson’s book The Occult2 that I’d read back in high school in the mid-1970s.

Ouspensky, an intellectual,

philosopher, and journalist well known in Moscow in the early 1900s, had also been

a great seeker of wisdom and had traveled far and wide throughout Asia in a

fruitless search for a teacher or teaching that could truly help him. He had

discovered nothing substantial. Disappointed, he returned to St.

Petersburg where shortly after he happened upon an ad for an

upcoming ballet in a Moscow

newspaper, cryptically entitled The

Struggle of the Magicians. Ouspensky attended this performance, which

consisted of finely choreographed dance sequences and mysterious demonstrations

of psychic abilities by a group of Russians garbed in the robes of Eastern

mystics. The whole performance was overseen by a dark, enigmatic, shaven-headed

man named Gurdjieff, who seemed to hold a remarkable spell over his dancers.

Intrigued, Ouspensky later attended an introductory meeting with the master and

his students. Though unimpressed with the students who for the most part

Ouspensky dismissed as young and gullible, he was unable to shake the

fascination he felt for Gurdjieff, with his intense eyes, the magnetic

self-assurance of his presence, and the depth of knowledge on esoteric matters he

seemed to possess. Though a formidable intelligence himself (Ouspensky had

already authored some well-known material on mathematics, philosophy, and

mysticism), he soon apprenticed himself to Gurdjieff.

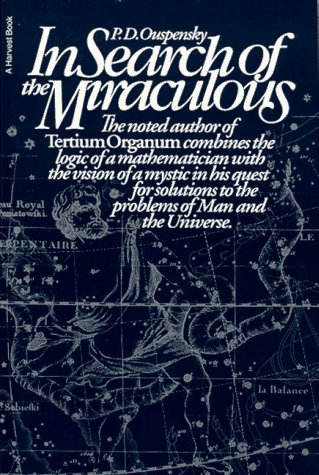

All of this is detailed in Ouspensky’s now famous book In Search of the

Miraculous3 which

my friend Peter the janitor recommended to me at the time. I read this work

several times over, and all these years later I still consider it one of the

best pieces of writing available on an extraordinary character and his esoteric

teachings, rarely surpassed, remarkable considering it was published in 1949

and concerns events that for the most part occurred between 1915 and 1924.

All of this is detailed in Ouspensky’s now famous book In Search of the

Miraculous3 which

my friend Peter the janitor recommended to me at the time. I read this work

several times over, and all these years later I still consider it one of the

best pieces of writing available on an extraordinary character and his esoteric

teachings, rarely surpassed, remarkable considering it was published in 1949

and concerns events that for the most part occurred between 1915 and 1924.

Not long after reading the book I found and was accepted into a Gurdjieff group in my city. It was led by a man who had studied at J.G. Bennett’s center, one of Gurdjieff’s more prominent direct disciples. I spent close to a year in this group. I eventually left and sought out more self-expressive forms of inner work (such as primal therapy and Reichian bodywork) and ended up in Osho’s movement. However years later I would take up my study of Gurdjieff again, readier this time to grasp more deeply his ideas and more properly utilize some of his practices.

I recall one incident from my time in the Work (as Gurdjieff’s system is known as) that revealed much of what it was all about. My teacher had asked me to report to his house one day for an assignment. Hoping that perhaps I was going to be the recipient of some special knowledge, I discovered at his door a simple note directing me to enter and proceed to one of the rooms. Once there I was confronted with an unopened box; it appeared to be some shelving from Walmart or something. There was a note on it as well. It read, “Please construct this steel shelf.”

That was my great assignment. Frustrated, I flashed back in my memory to a time two years earlier when a man I’d been having discussions with, a member of the Eckankar (an occult fraternity), was passing on some information to myself and another younger fellow we both worked with at the time. The younger guy was restless and irritated about something. After he left I asked my friend the Eckankar initiate what was wrong with the young man. He replied in his thick French accent, “He want to become God in one day” and then burst out laughing.

Impatience is a problem of the young, yet in the middle of assembling my teacher’s steel shelf I began to realize that the whole point lay in how I attended to the matter at hand. My mind was annoyed; I wanted personal attention and preferably some profound knowledge as well. And yet here I was with this silly shelf. What was spiritual about that? Everything, of course—and the practice of being mindful, staying alert, in the midst of the most mundane of things always remained the heart of Gurdjieff’s teaching. I managed to remain quite “present” while putting the shelf together and by the time I’d left, even without any contact with my teacher, I felt very good—balanced, clear, relaxed.

It is however of the greatest irony and interest that despite the core simplicity of Gurdjieff’s practical work (the complexities of his theory notwithstanding), his life and what led him to his teachings was anything but simple. In keeping with the other two subjects of this book his life was full of mystery and danger, of courage and adventure, and of extraordinary accomplishments.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

George Ivanovitch Gurdjieff was born in Alexandropol (today known as Gyumri), in the Caucasus region of Armenia, near the Turkish border, of a Greek father and an Armenian mother. Anyone who is aware of the legend of Gurdjieff is aware that the year of his birth has long been a mystery that has never been conclusively solved. One of his passports listed 1877, but he used several passports with different dates, and 1877 has been shown by many to be in error. His two chief biographers of more recent times, James Moore and William Patrick Patterson, argue for different dates, the former for 1866, the latter for 1872. My own estimate is closer to 1872.4

The uncertainty of his year of

birth is an excellent metaphor for the deeply enigmatic nature of the man

himself. The main problem with the history of Gurdjieff’s early years—reflected

in the mystery of his age—is that objectively speaking there is none. The sole source of information

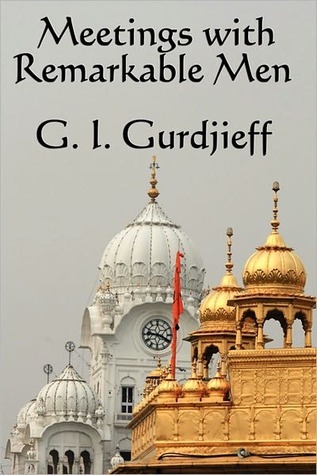

for his life up till around 1912 is his own writing, most notably one book, Meetings with Remarkable Men.5

The book is putatively about factual events but could

easily be partial fabrication or even outright allegory. Carlos Castaneda, the

controversial author of a number of influential books based on his (probably

fabricated) apprenticeship to an old Mexican Indian shaman, used to talk about

the idea of “erasing personal history” as a means of preventing oneself from

being trapped by the views and judgments of others. I know of no other

important recent figure in world spiritual tradition to have more effectively

erased—or perhaps more accurately blurred—his

personal history than Gurdjieff. (Interestingly, Castaneda’s date of birth was

long controversial as well).6

The uncertainty of his year of

birth is an excellent metaphor for the deeply enigmatic nature of the man

himself. The main problem with the history of Gurdjieff’s early years—reflected

in the mystery of his age—is that objectively speaking there is none. The sole source of information

for his life up till around 1912 is his own writing, most notably one book, Meetings with Remarkable Men.5

The book is putatively about factual events but could

easily be partial fabrication or even outright allegory. Carlos Castaneda, the

controversial author of a number of influential books based on his (probably

fabricated) apprenticeship to an old Mexican Indian shaman, used to talk about

the idea of “erasing personal history” as a means of preventing oneself from

being trapped by the views and judgments of others. I know of no other

important recent figure in world spiritual tradition to have more effectively

erased—or perhaps more accurately blurred—his

personal history than Gurdjieff. (Interestingly, Castaneda’s date of birth was

long controversial as well).6

One argument presented as to the reasons behind all these discrepantly dated passports is that Gurdjieff may have been working in espionage. However, as with Crowley’s alleged spy activities, nothing has ever been conclusively established in that area.

He grew up in Kars,

in northeast Turkey, a town

situated in the cultural melting pot region between the Black and Caspian Seas. This area was awash with a rich

mixture of different races and traditions, being a migratory meeting ground for

Asian and European peoples. Exposure to such variety was ideal to stimulate and

fire the imagination of a bright young boy destined to become one of the most

innovative and unique spiritual forces of the 20th century. As a youth

Gurdjieff made contact with many hermetic organizations, of political, occult,

philosophical, religious, and mystical natures. Though he witnessed and

experienced much that fascinated him, including a broad range of occult powers

and altered states of consciousness, he was fundamentally dissatisfied owing to

a failure to make contact with an authentic school of spiritual growth. At that

point he resolved to find such a school, as well as to search for ancient, lost

knowledge.

The Unverifiable History

The following information is entirely gleaned from Gurdjieff’s semi-autobiographical Meetings with Remarkable Men and has never been independently corroborated by anyone, so its veracity remains uncertain. (My own sense is that much of Meetings rings true, reading like typical travel stories. If anything was embellished it is likely connected to some of the key characters in the book, who may or may not have existed, and to the Sarmoung problem—see below). The book is nevertheless highly interesting, depicting as it does the archetypal hero’s quest to find the Grail of true wisdom.

To facilitate his search for lost knowledge Gurdjieff claimed that he and several others formed a loose organization of approximately twenty people called the “Seekers of Truth.” All the individuals of this group had in common a deep desire to make contact with bona fide spiritual sources, and as such the purity of their combined intention enabled them to accomplish much. They traveled far and wide, from the Holy Lands and Egypt (where Gurdjieff worked for a while as a tour guide) through Central Asia, up into Tibet, Mongolia, and Siberia. They combed archaeological ruins and eventually made contact with the Naqshbandi Dervishes, an authentic lineage of Sufi mystics.

Sometime in his early twenties

Gurdjieff traveled with the Seekers of Truth to Ani, in eastern Turkey

near the Armenian border. Back around 1000 AD Ani had been a major urban center

rivaling Baghdad or Cairo, but after being sacked by the Mongols

and other invaders over the centuries it gradually fell into ruin. By the time

Gurdjieff and his group were there it had been a ghost town for over a hundred

years.

Sometime in his early twenties

Gurdjieff traveled with the Seekers of Truth to Ani, in eastern Turkey

near the Armenian border. Back around 1000 AD Ani had been a major urban center

rivaling Baghdad or Cairo, but after being sacked by the Mongols

and other invaders over the centuries it gradually fell into ruin. By the time

Gurdjieff and his group were there it had been a ghost town for over a hundred

years.

While there Gurdjieff claimed that he and his friend Sarkis Pogossian, digging in the ruins of a decrepit church, found some crumbling old parchments. They had writing on them that was an archaic form of Armenian that neither Gurdjieff nor Pogossian could decipher. One parchment in particular grabbed their attention. It was a monk’s brief recounting of a “Sarmoung Brotherhood.” Gurdjieff and Pogossian recalled that they’d come across this name before in an Armenian book titled Merkhavat, and that it was the name of a “famous esoteric school” that had its roots in Babylon some twenty-five centuries before Christ. Gurdjieff further claimed that the Brotherhood could be traced up till the 600s AD, around the time of Mohammad, but after that all traces of it disappear. He and Pogossian then did considerable detective work, eventually concluding that the key link were the Aisors, descendents of the Assyrians, and that the Sarmoung Brotherhood was likely still based somewhere near the border region between Turkey and northwestern Iran.7

This is of course all very romantic. One has always to bear in mind the area Gurdjieff lived in. The ruins of Ani were a mere thirty miles from Alexandropol in northwestern Armenia, which served as a base for Gurdjieff and his band of seekers. The entire area was a fascinating playground for adventurous young men and women, and in his days many ruins were open and unattended. Archaeology was still a primitive science and the idea of historical preservation was only haphazardly recognized. So the idea that he and his friends could wander into the ruins of an ancient church, dig around, and find things is entirely believable. Whether the parchment story is true however is less certain; that part may be the embellishment that happens so commonly in stories involving a personal quest, so as to inject flavor—and in this case, that are designed to be a teaching allegory.

Gurdjieff said that what caught his attention about the Sarmoung legend was the claim that it was a custodian of great knowledge and secret mysteries. This, of course, was what he was looking for. Shortly after he and Pogossian went on a journey to a valley that the old parchments had indicated the Sarmoung had travelled toward. Gurdjieff later claimed that these parchments were written over a thousand years before, so the idea that he thought that the Sarmoung would still be in that valley after all that time indicates just how driven he was to find answers.

On the way there Pogossian was bitten by a venomous insect and in order to recover the two took refuge in the house of an Armenian priest. It was here that Gurdjieff discovered another old parchment belonging to the priest that had on it a map. The priest claimed that he was once offered a large sum of money for it that he refused, but that he subsequently accepted in exchange for a mere copy of the map. Gurdjieff then asked to see it and upon viewing it reacted strongly—“seized with violent trembling”8—because what he saw was what he’d spent long months thinking about. He said it was a map of “pre-sand Egypt”—Egypt as it was thousands of years ago, before the earliest period of recorded Egyptian history (that is, before 3500 BC). One day when the priest was out and about Gurdjieff stole into his room and furtively made a copy of the map.

This map resulted in Gurdjieff

temporarily abandoning his search for the Sarmoung in eastern Turkey and diverted him to Egypt. On the way he parted company

with Pogossian. While in Egypt

working as a tour guide he met the Russian Prince Yuri Lubovedsky. (It is very

amusing to read Gurdjieff’s description of being a guide: “In a few days I had

learned everything that a guide needs to know and began, along with slick young

Arabs, to confuse naïve tourists.”9 I was in Egypt in 1998, a century after

Gurdjieff had been there, and the sacred sites were still run by slick young

Arabs who were still busy confusing naïve tourists). Gurdjieff recounts a tale

where Lubovedsky—a wealthy aristocrat driven to a relentless spiritual search

by the death in childbirth of his young wife—becomes excited when he sees

Gurdjieff’s special map. The significance of this map and of Egypt in general would surface

years later when Gurdjieff would claim the following regarding the roots of

esoteric Christianity, and of his own teaching:

This map resulted in Gurdjieff

temporarily abandoning his search for the Sarmoung in eastern Turkey and diverted him to Egypt. On the way he parted company

with Pogossian. While in Egypt

working as a tour guide he met the Russian Prince Yuri Lubovedsky. (It is very

amusing to read Gurdjieff’s description of being a guide: “In a few days I had

learned everything that a guide needs to know and began, along with slick young

Arabs, to confuse naïve tourists.”9 I was in Egypt in 1998, a century after

Gurdjieff had been there, and the sacred sites were still run by slick young

Arabs who were still busy confusing naïve tourists). Gurdjieff recounts a tale

where Lubovedsky—a wealthy aristocrat driven to a relentless spiritual search

by the death in childbirth of his young wife—becomes excited when he sees

Gurdjieff’s special map. The significance of this map and of Egypt in general would surface

years later when Gurdjieff would claim the following regarding the roots of

esoteric Christianity, and of his own teaching:

The Christian form of worship was not invented by the fathers of the church. It was all taken in a ready-made form from Egypt, only not from the Egypt that we know but from one which we do not know. This Egypt was in the same place as the other but it existed much earlier…It may seem strange to people when I say that this prehistoric Egypt was Christian many thousands of years before the birth of Christ, that is to say, that its religion was composed of the same principles and ideas that constitute true Christianity.10

Egypt of course no longer practices the religion of its ancient ancestors, be those prehistoric or even of the Pharaonic ages. Egypt for many centuries has been a Muslim nation and as such the prime esoteric tradition found now within its borders is Sufism. The Sufi tradition (the mystical undercurrent of Islam) unquestionably had a most profound impact on the consciousness of the young Gurdjieff and from it he likely derived some of the ritual dances, meditation techniques, and sacred symbols (such as the enneagram) that he would employ in his later teaching years.

After leaving Egypt Gurdjieff wandered throughout the region—including visits to Medina and Mecca in disguise—before eventually drifting east again toward central Asia and finally, he claimed, being led to the Sarmoung monastery that was somewhere in or near Afghanistan. The exact location of the monastery remained a mystery even to Gurdjieff, as he said he was taken there blindfolded for a journey that lasted several days. Some of his main teachers resided in this school and he found, to his great surprise, that his old friend Prince Lubovedsky was there also. This was around the year 1899. And so in an interesting parallel with Crowley as one young seeker is entering the esoteric order (the Golden Dawn) in England that will train him, at the same time the other is entering a mysterious monastery in a geographic null zone that will train him.

However as mentioned earlier no one has ever been able to locate this monastery or Brotherhood, and it seems very possible that Gurdjieff fabricated this part of his past. If so he will not be the first or last to do so. High profile examples of this found in the 20th century include T. Lobsang Rampa and Carlos Castaneda—both enormously influential writers who claimed they’d spent time in far off remote places apprenticed to advanced spiritual masters (Tibetan masters in Rampa’s case, and a Mexican Indian shaman in Castaneda’s case). Both were subsequently proved to be almost beyond doubt frauds that had made their stories up, though some believe that there is a chance that at least part of Castaneda’s story was authentic—Rampa, however, was shown to be an outright imposter.

Real or allegorical, after Gurdjieff left the Sarmoung monastery he was not done exercising his wanderlust and headed off to Tibet where he claimed to absorb some of the Tibetan Tantric teachings and observe the sacred dances. He was not, however, the famous Buryat Mongol Aghwan Dorjieff, a prominent Tibetan official, as some writers have mistakenly assumed.

The problem of mistaken

identity and other enigmas seemed to follow Gurdjieff around. From an early age

he acquired a reputation for being something of an opportunist, and at times

even an outright confidence trickster. This was usually connected to money

issues and his lifelong struggle to generate funds to keep his travel, research

and later work going. In his twenties he was a true jack of all trades doing

whatever he could—carpet mender, tour guide, hypnotist, etc.—to finance his

travels. He once captured some small birds, painted them, and then sold them

(for a costly fee) as “exotic American canaries.” The next day it rained and

Gurdjieff hastily fled town before his creativity was unmasked.

There is some evidence that in his thirties Gurdjieff functioned as a covert

political agent and spy for the Russian government, though his motivation for

doing so would most likely have been to attain the funds and travel capacity to

continue his search for knowledge. He lived in a time of great political

upheaval and religious foment. Much of his teaching work took place in times

(the Russian Revolution and the two World Wars) and places that made travel and

even survival difficult, let alone having the leisure time to do spiritual

practices. However Gurdjieff was a master of situations and could use even the

most arduous conditions as a vehicle for intensifying work upon self. This is

consistent with what all the masters have taught, that growth happens more

effectively in the soil of insecurity. When things are too stable and safe we

tend to go to sleep, as when it is dark and quiet at night.

By approximately 1900 the Seekers of Truth had disbanded. Gurdjieff’s life

around that time continued to be full of adventure: he spent some time in Persia

where he studied magic with some magi; he met the Russian Tsar Nicholas II; and

on three separate occasions during those years he claimed he was accidentally

shot by warring soldiers, narrowly escaping death. The worst of these

misadventures occurred in Tibet

where he spent several months hovering between life and death as he slowly

healed from a bullet wound.

After his Tibetan adventure he

spent two years participating in an unknown Sufi community, although it may

well have been one of the Naqshbandi Order, some of whose teachings resemble

his later system. While the Sarmoung story may be myth his association with

this latter Sufi community has the ring of truth. The Naqshbandi Sufi Order is

well known.

After his Tibetan adventure he

spent two years participating in an unknown Sufi community, although it may

well have been one of the Naqshbandi Order, some of whose teachings resemble

his later system. While the Sarmoung story may be myth his association with

this latter Sufi community has the ring of truth. The Naqshbandi Sufi Order is

well known.

After completing his time in

the Sufi community he was, essentially, a fully qualified spiritual teacher in

his own right. The year was around 1907 and he was around thirty-five years

old. He had already lived an extraordinary life full of adventure and

character-building hardships. He had the ability to capture and direct the

attention of others, as well as possessing a great depth of esoteric knowledge

and teaching methods acquired from his many years of travels and contacts with

extraordinary people. But more crucially he had embodied what he had been

taught, attaining, through his own fierce efforts an internal unity that

clearly marked him apart from the sleeping, “mechanical” man.

At this point Gurdjieff settled in Tashkent, in

Russian Turkestan (present day Uzbekistan,

a few hundred miles north of Afghanistan—or

as a wandering friend of mine once called it, “far away-istan”). Here he set

himself up as a kind of teacher-magician-healer, often slipping into deliberate

roguery so as, as he claimed it, to further his study of human mechanical

behavior and reactivity, but doubtless also to make a buck in order to fund his

survival and travel. He was also successful in business, trading in several

commodities. By around 1910 Gurdjieff began to develop and formulate the

teaching system that would eventually be his legacy to the world. This period

marks an important and interesting juncture in his life. In his short (and

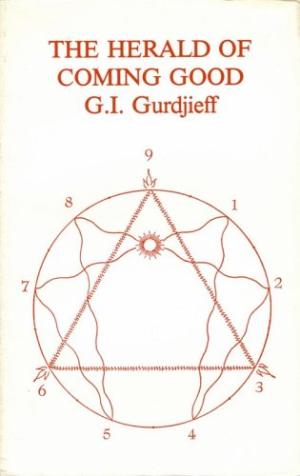

eventually self-repudiated) work The

Herald of Coming Good, written in 1932, Gurdjieff claimed that “twenty-one

years ago”—that is, in 1911— he bound himself to live “an artificial life” that

involved renouncing his capacity to manipulate others via charisma and

knowledge of hypnosis, allegedly for the purpose of further self-purification.

This is an important topic to consider touching as it does on the role and

legitimacy of a rogue-type guru. The main point here is that Gurdjieff was

saying, basically, that he was dedicating his life to the “Bodhisattva spirit”—that

is, to help others wake up, rather than to only serve himself.

At this point Gurdjieff settled in Tashkent, in

Russian Turkestan (present day Uzbekistan,

a few hundred miles north of Afghanistan—or

as a wandering friend of mine once called it, “far away-istan”). Here he set

himself up as a kind of teacher-magician-healer, often slipping into deliberate

roguery so as, as he claimed it, to further his study of human mechanical

behavior and reactivity, but doubtless also to make a buck in order to fund his

survival and travel. He was also successful in business, trading in several

commodities. By around 1910 Gurdjieff began to develop and formulate the

teaching system that would eventually be his legacy to the world. This period

marks an important and interesting juncture in his life. In his short (and

eventually self-repudiated) work The

Herald of Coming Good, written in 1932, Gurdjieff claimed that “twenty-one

years ago”—that is, in 1911— he bound himself to live “an artificial life” that

involved renouncing his capacity to manipulate others via charisma and

knowledge of hypnosis, allegedly for the purpose of further self-purification.

This is an important topic to consider touching as it does on the role and

legitimacy of a rogue-type guru. The main point here is that Gurdjieff was

saying, basically, that he was dedicating his life to the “Bodhisattva spirit”—that

is, to help others wake up, rather than to only serve himself.

Beginning of Verifiable History

From here on in we are on solid historical ground, knowing more or less without

question that the following events in Gurdjieff’s life in fact occurred.

After a few years in Tashkent, Gurdjieff drifted west toward the big cities of Russia.

In 1912 at approximately age forty, he arrived in Moscow

and shortly after in St. Petersburg

married a beautiful young Polish woman, Julia Ostrowska. Her background is

unclear—in some accounts she is described as a lady of the Tsar’s court, and in

other cases as a penniless woman from a destitute family whom Gurdjieff

rescued. Occam’s razor suggests the latter version is the more likely of the

two. At any rate she remained his wife until her death from cancer in 1926. She

was described once by Katherine Mansfield, who was with her at the Prieure

briefly in late 1922, as having the “bearing of a queen.” But otherwise she

retained a very low profile. There are few photographs of her. By all accounts

she was both a loyal partner and a devoted student of Gurdjieff at the same

time. It was said that she retained her last name in order to make it clear

that she was merely another of Gurdjieff’s students. Despite this humility,

Gurdjieff once stated that she was a “very old soul.”11

After a few years in Tashkent, Gurdjieff drifted west toward the big cities of Russia.

In 1912 at approximately age forty, he arrived in Moscow

and shortly after in St. Petersburg

married a beautiful young Polish woman, Julia Ostrowska. Her background is

unclear—in some accounts she is described as a lady of the Tsar’s court, and in

other cases as a penniless woman from a destitute family whom Gurdjieff

rescued. Occam’s razor suggests the latter version is the more likely of the

two. At any rate she remained his wife until her death from cancer in 1926. She

was described once by Katherine Mansfield, who was with her at the Prieure

briefly in late 1922, as having the “bearing of a queen.” But otherwise she

retained a very low profile. There are few photographs of her. By all accounts

she was both a loyal partner and a devoted student of Gurdjieff at the same

time. It was said that she retained her last name in order to make it clear

that she was merely another of Gurdjieff’s students. Despite this humility,

Gurdjieff once stated that she was a “very old soul.”11

At this time he also attracted

his first Western students. In 1914 he staged his famous ballet The Struggle

of the Magicians, which was attended by Peter Ouspensky. This meeting was

pivotal for both men. As mentioned, Ouspensky was not the typical seeker as he

had already traveled extensively, experimented with consciousness, and was the

author of Tertium Organum12,

a philosophical work that came to achieve world-wide acclaim. On Ouspensky’s

return from his travels he lectured in Moscow

to audiences of over a thousand people, and yet such attention did not unduly

swell his head. He was man of true intelligence and thus was able to recognize

his own ignorance when confronted with it. Thus he submitted himself to a

teacher-student relationship with Gurdjieff.

.gif?timestamp=1518917446808) The importance of the relationship between these two men cannot be stressed

enough. Ouspensky was to Gurdjieff much like Plato was to Socrates: the former

a razor sharp intellect and consummate communicator; the latter a man of

exceptional being whose mere force of presence was testament to a great

deal of raw life experience, as well as the efforts he had made to transform

himself.

The importance of the relationship between these two men cannot be stressed

enough. Ouspensky was to Gurdjieff much like Plato was to Socrates: the former

a razor sharp intellect and consummate communicator; the latter a man of

exceptional being whose mere force of presence was testament to a great

deal of raw life experience, as well as the efforts he had made to transform

himself.

Though Ouspensky has typically been regarded as Gurdjieff’s “chief disciple,”

this is mostly misleading. In fact Ouspensky only studied deeply with his

teacher for a few years (from 1915-18). From 1919-1924 he was vacillating,

going back and forth and more than once breaking with Gurdjieff. By 1924 he was

essentially complete with him (they met sporadically for a few more years until

a final meeting in 1931 in Paris).

The reasons for his break have never been clear, mostly because Ouspensky

himself never fully explained it; however, it seems clear enough from the

records that there was something in Gurdjieff’s intensity that was ultimately

too much for Ouspensky. He became convinced that Gurdjieff and the system (his

body of ideas) must be clearly distinguished from each other. Gurdjieff’s brash

volatility, crude humor, and sudden changes in behavior doubtless alienated the

intellectual and cultured Ouspensky who in the end believed it was risky to be

associated with Gurdjieff. He actually went so far as to forbid his own

students, in later years, from ever mentioning Gurdjieff by name. In light of

his eventual break with him Ouspensky’s perception of his teacher was

interesting. He once said,

Mr. Gurdjieff is a very extraordinary man. His possibilities are much greater than those of people like ourselves. But he can also go in the wrong way…Most people have many “I”s. If these “I”s are at war with one another it does not produce great harm, because they are all weak. But with Mr. Gurdjieff there are only two “I”s, one very good and one very bad.”13

As to the reasons behind this position, some senior students of the Gurdjieff Work have seen Ouspensky as being caught in an ego-trap from which he could not free himself. He was too attached to his own sense of “right,” and did not embrace the physical-emotional aspect of the Work. This created an imbalance in his development that made him unable to see his deeper character flaws, thus necessitating him to project these onto his teacher, whereupon Gurdjieff was perceived as a “danger.”

A more prosaic psychological explanation is even more probable, being that Ouspensky, like Gurdjieff, was an autocrat and used to having the stage himself—and like so many males, came to feel competitive with his alpha-male teacher. He wanted to learn from Gurdjieff at the beginning and was convinced that Gurdjieff had something that he could learn about. And so, he repressed his more egocentric need for recognition long enough to gain the information from Gurdjieff that he wanted. Once he had this information his “inner leader” began to resurface, making it very difficult for him to remain in a subordinate position to another teacher, and a very autocratic one at that. The fact that Ouspensky went to England and set himself up as a teacher there (teaching Gurdjieff’s material to boot) seems clear evidence that he was driven to teach more than anything. All that, combined with Gurdjieff’s relentless pressing of Ouspensky’s buttons, was more than enough to cause the full break.

In Moscow in 1912 Gurdjieff

had began to slowly form his first groups. Over the next four years, teaching

mostly in St. Petersburg and Moscow, he drew to him some of his key

students; in addition to Ouspensky, Dr.

Stjoernval, Zaharoff, and Thomas and Olga de Hartmann. During this time Russia had become embroiled in the First World

War; that, followed by the Russian Revolution of 1917 that brought down the

Tsarist aristocracy and eventually led to the formation of the Soviet Union, made for a highly unstable atmosphere. From

1917 to 1919 Gurdjieff and his small band of followers were often in real

danger and were constantly on the go, moving between Russia and the Caucasus

region of Georgia and Armenia, staying variously at Tuapse and Sochi on the

Black Sea coast, Essentuki in southern Russia, and finally at Tbilisi (then

known as Tiflis) in central Georgia, midway between the Black and Caspian Seas.

All the while during this time Gurdjieff continued to teach, and work with all

of his students directly. It was the very antithesis of a staid monastic or

ashram environment. This was live-fire work on self.

In Moscow in 1912 Gurdjieff

had began to slowly form his first groups. Over the next four years, teaching

mostly in St. Petersburg and Moscow, he drew to him some of his key

students; in addition to Ouspensky, Dr.

Stjoernval, Zaharoff, and Thomas and Olga de Hartmann. During this time Russia had become embroiled in the First World

War; that, followed by the Russian Revolution of 1917 that brought down the

Tsarist aristocracy and eventually led to the formation of the Soviet Union, made for a highly unstable atmosphere. From

1917 to 1919 Gurdjieff and his small band of followers were often in real

danger and were constantly on the go, moving between Russia and the Caucasus

region of Georgia and Armenia, staying variously at Tuapse and Sochi on the

Black Sea coast, Essentuki in southern Russia, and finally at Tbilisi (then

known as Tiflis) in central Georgia, midway between the Black and Caspian Seas.

All the while during this time Gurdjieff continued to teach, and work with all

of his students directly. It was the very antithesis of a staid monastic or

ashram environment. This was live-fire work on self.

The Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man

It was in Tbilisi in Georgia in October of 1919 that Gurdjieff officially opened his Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man, with a nucleus of six students—Stjoernval, the de Hartmanns, Alexandre and Jeanne de Salzmann, and his wife Julia Ostrowska. (Ouspensky by that time already had his first break with Gurdjieff, and had returned to St. Petersburg—renamed Petrograd by then—although he would shortly rejoin his teacher, before breaking with him again not long after). The political instability in Georgia by then was such that Gurdjieff had to leave within six months. At that time his following had grown to about thirty disciples. In the spring of 1920 they went west to Istanbul, Turkey (then known as Constantinople). There, in October of that year, Gurdjieff reopened his Institute.

During this time Gurdjieff was beset with considerable personal loss—his father, along with one of his sisters and all her children, had been killed by Turks in 1918 and 1920 respectively. The hardships, both outer and inner, that he and his small group of dedicated students had to endure was extraordinary, and yet it also dovetailed with the very nature of Gurdjieff’s system, which was to work directly with the harsh conditions of life, and to maintain presence of mind—clear attention—in the face of it all.

The Institute’s

duration in Istanbul was, as with its initial

period in Tbilisi,

around six months. By May of 1921 Gurdjieff had closed it owing to problems

attracting students. At that point Gurdjieff made the decision to relocate to

Europe, and in August he arrived in Berlin,

Germany. The

next winter he visited London briefly, hoping to

open his school in England,

but plans for that fell through. However in October of 1922, with the help of a

wealthy English benefactress—Mary Lilian, the Lady Rothermere (wife of Lord

Rothermere, the newspaper magnate)—he made a down payment on the Chateau de

Pieure des Basses Loges, at Fontainbleau-Avon, forty miles southeast of Paris,

France. At fifty years of age Gurdjieff had finally found a long-term base for

his teachings that would serve as his first true commune. After years of

constant move, throughout Russia

and Asia Minor, dodging revolutions and wars,

he and his community of students at last were able to settle in surroundings

that enabled them to deepen their practice of the Work. The Prieure was now the

headquarters for his Institute.

The Work at the Prieure consisted of the essentials of Gurdjieff’s System: hard

physical labour accompanied by active meditations, chief of which were

“self-observation” and “self-remembering.” Individual assignments were given to

students fitting their unique requirements for growth. A special Study House

was built for the practice and performance of the Sacred Dances and Movements,

ancient rituals that Gurdjieff learnt during his years in Sufi monasteries.

The Work at the Prieure consisted of the essentials of Gurdjieff’s System: hard

physical labour accompanied by active meditations, chief of which were

“self-observation” and “self-remembering.” Individual assignments were given to

students fitting their unique requirements for growth. A special Study House

was built for the practice and performance of the Sacred Dances and Movements,

ancient rituals that Gurdjieff learnt during his years in Sufi monasteries.

It was not an easy place to be. This Work was unlike the sweet-coated dross and

tepid sentimentality that passes for much new age or personal growth work

nowadays. Gurdjieff was a fierce, unrelenting taskmaster, but capable of

extraordinary compassion at unexpected moments. However the basis of his system

was effort and more effort. “No growth is possible,” he would say, “without

conscious labour and voluntary suffering.” By this he meant that we cannot

attain something without payment, or sacrifice—not in the sense of morbid

self-punishment, but rather in the necessity of giving something up in order to

make space for something new. What we “give up” can be something intangible

like low self-worth, or even laziness, or some other character defect like

vanity or pride.

In 1924 Gurdjieff and

thirty-five members of his community sailed to the U.S., where they staged

demonstrations of the Sacred Dances in New York, Chicago, Boston, and

Philadelphia. While there, he attracted several key people who would further

his cause in America,

such as Margaret Anderson, Jane Heap, Jean Toomer, and C.S. Nott. Later that

same year, while back in France, Gurdjieff, a notoriously aggressive driver,

had a serious auto crash, and was not expected to live. However he recovered,

no doubt aided by his powerfully crystallized will. Shortly after this to the

shock of everyone he disbanded the community and Institute. This was revealed

though in short time to be something of a ploy to rid himself of his less

dedicated students, whom he no longer felt he had sufficient energy reserves to

freely give them. He continued to work with a smaller nucleus that remained

with him, students who were more supportive of him and less demanding of his

energy.

Gurdjieff’s mother and wife passed away in 1925 and 1926 respectively. After

this he began a phase of more introspective work, beginning his magnum opus Beelzebub’s

Tales to His Grandson,14 and working on numerous musical

compositions with Tomas de Hartmann. This music was designed to evoke an

opening of the “higher emotional center” (see Chapter 5 for more on this) and

when experienced in combination with the Sacred Dances, elicited an obvious

sense of the transcendent and ineffable. The same was true of Gurdjieff’s

writings, though operating through the intellectual center. These were examples

of what he called Objective Art, which had the capacity to catalyze the

observer into an awakened state of consciousness. Such art was based on a form

of higher mathematics that nowadays goes by the term “sacred geometry.” Other

examples of Objective Art are the Egyptian pyramids, Tibetan tangka

paintings, the Taj Mahal, Stonehenge, etc.

Gurdjieff distinguished these from subjective art, which includes almost all

conventionally known forms of art.15

Gurdjieff’s Work at the Prieure lasted for ten stormy years until its enforced closure in 1932. By that time he had effectively assigned many of his students to leave him, and even had to intentionally alienate some of them to do this. In this sense Gurdjieff was authentic in that he understood the delicate task a true teacher has, i.e. having to know when it is right for a student to leave, in order to avoid the dangerous consequences of attachment and dependency. Such a leave-taking is rarely easy and often traumatic as the student has opened themselves completely to the teacher, much as a child to a parent and thus is highly susceptible to being hurt. Depending on the consciousness and compassion of the teacher the separation can be engineered with grace, but that of course is not always the case. More than one teacher-student relationship has ended via a painful rupture of one sort or another.

It should also be noted that Gurdjieff appeared to engineer some of these separations as a means of keeping his own consciousness sharp, via conscious labor and voluntary suffering. To part from those he had great fondness for was his way of keeping himself from losing consciousness due to excessive ease and comfort.

Gurdjieff appeared

uninterested in allowing himself to be deified, or his community to be turned

into a cult. Personalities with cultic tendencies who gathered around him

tended to find it difficult to stay long, if they did not cease their psychic

dependency on him. (He even complained that while recuperating from his car

crash in 1924 people would visit him who simply wanted to suck energy out of

him—doubtless as much related to his commanding autocratic nature as to their

dependency). This periodic tendency to push students away, though sometimes

causing pain for those attached to him, nevertheless marked him apart from the

usual run of leaders in typical organizations, be they religious or secular,

who are primarily interested in simply acquiring more and more subordinates. As

“the Oracle” said to Neo in one of the Matrix

films, “What do all men who have power want? More power.” That said, Gurdjieff was without doubt a master

manipulator, and so his true motive for pulling students toward him or pushing

them away was not always clear. He did, unquestionably, have a “planetary aim,”

and was dedicated to that. That is, his life was not governed as the average

person’s life is governed, by personal aims. He had a powerful vision, and was

entirely a Western bodhisattva—someone motivated by deep compassion for the

human condition. As J.G. Bennett said, “He was fundamentally good.” But he was

also often ruthless. It is this quality, ruthlessness, that is so feared and

yet respected by others. It makes for a sharply defined character, one who

commands attention just by walking into a room.

In 1934 Gurdjieff met Frank Lloyd Wright, the famous architect, and the two

connected very well, though it is doubtful that Wright became a student in any

sense of that term, as is sometimes believed. Wright had married one of

Gurdjieff’s former students, Olgivanna Hinzenberg. Speaking of Gurdjieff,

Wright, with an architect’s eye for observation, once gave a fascinating

account of the old Magus:

In 1934 Gurdjieff met Frank Lloyd Wright, the famous architect, and the two

connected very well, though it is doubtful that Wright became a student in any

sense of that term, as is sometimes believed. Wright had married one of

Gurdjieff’s former students, Olgivanna Hinzenberg. Speaking of Gurdjieff,

Wright, with an architect’s eye for observation, once gave a fascinating

account of the old Magus:

Gurdjieff, declaring all mankind idiots, divides them into three classes—those who take what they can get; those who get what they can take; those who get what they get…There is enormous ego in this man. Always deliberate in movement, not large although he seems so—with the skull bald and tall behind—forceful humorous luminous eyes. In him we see a massive sense of his own individual worth. A man able to reject most of the so-called culture of our period and set up more simple and organic standards of personal worth and courageously, if outrageously, live up to them. He affected us strangely as though some oriental buddha had come alive in our midst…A kind, solid, fatherly man. All that went on about him seemed to impress him little and yet he would later give evidence that nothing escaped him, so highly are his powers of observation and concentration developed…perhaps the personality of Gurdjieff is somewhat similar to that of Gandhi only, of course, more robust, aggressive and venturesome in nature. Now a man of perhaps 85 looking 55, he has some 40,000 “followers”—he will not call them students or disciples—has 104 sons of his own and 27 daughters for all of whose education he has made provision and to which he has given his attention.…His knowledge of human nature and all its foibles seems perfect, and he does not hesitate to use this knowledge for his own ends although with a conscience that sees to it that they get something worthwhile out of his meeting them. Not caring at all for America or Americans, he has come over here, as he frankly put it, “to shear the sheep.” He will turn the wool into some kind of good work for humanity. His hypnotic powers have served him well in this connection, but he is more careful now in exercising them. American fruits and foods he finds unfit to eat—likes only our tomato juice and our dollars. But eats enormously just the same. The style of our money he approves. But the shearing I imagine is not so good. The wool is now so short. Notwithstanding a superabundance of personal idiosyncrasy, George Gurdjieff seems to have the stuff in him of which our genuine prophets have been made. And when prejudice against him has cleared away, his vision of truth will be recognized as fundamental to the man men need.16

The biblical numbers cited (doubtless sincerely) by Wright above—“40,000 followers, 104 sons and 27 daughters”—is a highly amusing example of Gurdjieff’s bluster and willingness to pull anyone’s leg, especially that of a famous man.

From his middle age and beyond

Gurdjieff, like Crowley,

had recurrent financial problems and in his later years relied mostly on

American disciples to fund his continued efforts to promote the Work. By 1938

Jeanne de Salzmann had emerged as Gurdjieff’s chief deputy, running a

successful group in Paris

dedicated to the Work. She would eventually head up the international Gurdjieff

Foundation and competently lead it for years after the master’s death,

outliving all the original students in the process until passing away in 1990

at the age of 101. It is an interesting fact that a number of Gurdjieff’s

prominent female students lived to advanced ages. Examples were Olga de

Hartmann (94), Sophie Ouspensky (89), Olgivanna Lloyd Wright (86), Jane Heap

(81), Annie Staveley (90), Solito Solano (87), Katherine Hulme (81), and

Margaret Anderson (87). A number of these women--all accomplished writers and intellectuals--formed a group called 'The Rope', dedicated to applying Gurdjieff's teachings in a practical manner. Several published books on their years with the master after his death.

From his middle age and beyond

Gurdjieff, like Crowley,

had recurrent financial problems and in his later years relied mostly on

American disciples to fund his continued efforts to promote the Work. By 1938

Jeanne de Salzmann had emerged as Gurdjieff’s chief deputy, running a

successful group in Paris

dedicated to the Work. She would eventually head up the international Gurdjieff

Foundation and competently lead it for years after the master’s death,

outliving all the original students in the process until passing away in 1990

at the age of 101. It is an interesting fact that a number of Gurdjieff’s

prominent female students lived to advanced ages. Examples were Olga de

Hartmann (94), Sophie Ouspensky (89), Olgivanna Lloyd Wright (86), Jane Heap

(81), Annie Staveley (90), Solito Solano (87), Katherine Hulme (81), and

Margaret Anderson (87). A number of these women--all accomplished writers and intellectuals--formed a group called 'The Rope', dedicated to applying Gurdjieff's teachings in a practical manner. Several published books on their years with the master after his death.

Throughout World War Two Gurdjieff resided in Paris, where he worked with a large group of French

students. Now in old age, he remained mostly in his famous flat on Rue des

Colonels Renard, entertaining students and seekers with his outrageous humor

and lavishly prepared meals. During this time he developed the ritual Idiot

Toasts, yet another of his methods designed to diminish self-importance. His

writings were prepared for publication; these were, along with the years of

their publication:

The Herald of Coming Good (1933—a slim

volume later withdrawn from publication and repudiated by Gurdjieff).

The Herald of Coming Good (1933—a slim

volume later withdrawn from publication and repudiated by Gurdjieff).

Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson (1950). Gurdjieff intended that this book be read first; its purpose being to break down the student’s rigid and conditioned views of reality.

Meetings with Remarkable Men (1963—later made into a film by Peter Brook in 1979). This book was to be read second, its purpose being to introduce to the student a new way of thinking and perceiving reality and the possibilities of being.

Views from the Real World (1973). A collection of talks given by Gurdjieff, mostly from the 1920s. It is not an official part of his canon All and Everything.

Life is Real Only Then, When “I Am” (1975). This was to be read third, its purpose being to teach the student how to interact with life and encounter reality.

Apart from Herald, Gurdjieff did not live to see

the publication of any of these works, although he approved the final proofs of

Beelzebub shortly before he died.

Three of them—Beelzebub, Meetings, and Life—were termed collectively All and Everything, 1st, 2nd,

and 3rd series). It is unclear what took these books so long to get published,

although doubtless it reflects the difficulty the public had with understanding

Gurdjieff’s ideas, let alone having a means to recognize and appreciate who he

was.

In 1947 Ouspensky died, according to some sources as a disillusioned drunkard,

according to others as a genuine saint, but in reality probably a bit of both.

He failed to reconcile with Gurdjieff, though he had been invited to Paris by the master

shortly before his death. In 1948 Gurdjieff authorized Mme. Ouspensky, herself

a respected teacher of the Work, to publish her husband’s Fragments of an

Unknown Teaching (later re-titled In Search of the Miraculous). Upon

looking over the manuscript Gurdjieff was impressed by Ouspensky’s memory. He

remarked “For long time I hate this man. Now I love him.” This book was

published in 1949.

In October of 1949, in (probably) his late seventies, Gurdjieff’s health

failed, and he died shortly after. His final instructions on his death bed were

to Jeanne de Salzmann, who later that year organized the re-grouping of the

scattered body of Gurdjieff students and communities under the collective

banner of the Gurdjieff Foundation.

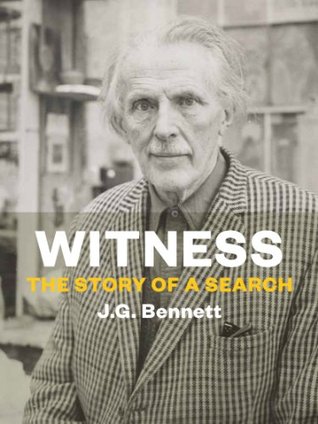

J.G. Bennett probably became the most influential and effective Gurdjieff

exponent not affiliated with the Gurdjieff Foundation, opening his own school

in England, which later

spread to America.

Bennett was a prolific author and became a guru in his own right, and he always

acknowledged Gurdjieff as his main inspiration. Next to Ouspensky, he did the

most to transmit his master’s knowledge, despite receiving rough treatment from

some, especially Ouspensky, who criticized Bennett heavily for teaching (in Ouspensky’s

opinion) before he was ready and without authorization. Bennett died in 1974. During

his life Gurdjieff remained largely obscure and unknown, and when he was

recognized, it was with more notoriety than anything else. Two of his students,

Ouspensky and the literary figure A.R. Orage, were far more renowned. After

Gurdjieff’s death, however, his fame slowly spread. Like Crowley, he grew enormously in stature and

recognition only several decades after his death.

J.G. Bennett probably became the most influential and effective Gurdjieff

exponent not affiliated with the Gurdjieff Foundation, opening his own school

in England, which later

spread to America.

Bennett was a prolific author and became a guru in his own right, and he always

acknowledged Gurdjieff as his main inspiration. Next to Ouspensky, he did the

most to transmit his master’s knowledge, despite receiving rough treatment from

some, especially Ouspensky, who criticized Bennett heavily for teaching (in Ouspensky’s

opinion) before he was ready and without authorization. Bennett died in 1974. During

his life Gurdjieff remained largely obscure and unknown, and when he was

recognized, it was with more notoriety than anything else. Two of his students,

Ouspensky and the literary figure A.R. Orage, were far more renowned. After

Gurdjieff’s death, however, his fame slowly spread. Like Crowley, he grew enormously in stature and

recognition only several decades after his death.

A large part of Gurdjieff’s task was the transmitting of Eastern and Middle

Eastern esoteric knowledge to the West, namely Europe and North

America. In succeeding in this (though his success became clearly

apparent only after his death) he was one of the chief forces contributing

toward what became known as the human potential movement and related

developments in transformational work of the late 20th century. Just

a few examples, of great varying degree of quality: In addition to Ouspensky’s

body of work, that of J.G. Bennett and the Claymont Institute; Maurice Nicoll,

Kenneth Walker, Rodney Collin; Maxwell Maltz’s conception of

“psycho-cybernetics” based on the idea that our brain and nervous system are

“servo-mechanisms” that can be controlled by our consciousness—notice the link

with Gurdjieff’s idea that man is a “machine”; Maltz’s ideas were borrowed and

developed by Werner Erhard via his est teachings; the entire Enneagram

Personality System industry as developed by Ichazo and Naranjo; the Michael

Teachings, a series of popular new age books alleging to represent a body of

information “channeled from fifth dimensional entities” but which is in fact

heavily borrowing from Gurdjieff’s ideas; common modern terms such as “The

Work,” “Work on oneself,” and “awakening,” now more or less household

expressions amongst those involved in personal growth or transpersonal work,

were all originally Gurdjieff expressions.

Ouspensky was an essential component of this accomplishment. More than any other, he brought Gurdjieff’s ideas to large numbers of people in the West. In fact, his work In Search of the Miraculous, the account of his years with Gurdjieff, has been far more widely read than any of Gurdjieff’s own published writings. It is one of a small number of 20th century Western classics of spirituality, up there with Earnest Holmes’ The Science of Mind, Maxwell Maltz’s Psycho-Cybernetics, Crowley’s Magick: Book Four, Helen Schucman’s A Course In Miracles, and Alan Watts’ The Book.

The jury remains out on

Gurdjieff the man—he could be both kind and brutal, and above all, intimidating. As John Carswell put it,

“He had the power of controlled fury, which commands instant obedience.”17

However there is little doubt about the value and usefulness of the system he

left behind, which is almost certainly all he would have cared about anyway. There

is also little doubt about the influential impact he and his Work have had on

so many tens of thousands throughout the world, the vast majority of whom never

met him.

The jury remains out on

Gurdjieff the man—he could be both kind and brutal, and above all, intimidating. As John Carswell put it,

“He had the power of controlled fury, which commands instant obedience.”17

However there is little doubt about the value and usefulness of the system he

left behind, which is almost certainly all he would have cared about anyway. There

is also little doubt about the influential impact he and his Work have had on

so many tens of thousands throughout the world, the vast majority of whom never

met him.

Gurdjieff, much like the protagonist of his magnum opus Beelzebub, was a stranger in a strange land. He was exceptionally unique, a wizard from another world, but paradoxically he was also very human. Ultimately however, like all true Magi, there was something unapproachable about him—or as his student Margaret Anderson put it, he was the “unknowable Mr. Gurdjieff.” The essence of the man and his life was probably best summarized by this well known quote from his Russian disciple Rachmilievitch: “God give you the strength and courage, Gurdjieff, to endure your lofty solitude.”

1. William Patrick Patterson, Eating the “I” (San Anselmo: Arete Communications, 1992, p. 36).

2. Colin Wilson, The Occult (London: Grafton Books, 1972, reprinted many times).

3. P.D. Ouspensky, In Search of the Miraculous: Fragments of an Unknown Teaching (Orlando: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc., 1949).

4. Gurdjieff had different passports over the years that gave different birth dates. The most common years given for his birth are 1872 and 1877. James Moore, in his comprehensive biography (Gurdjieff: Anatomy of a Myth) argued for 1866, and since the publication of Moore’s book in 1991, this date seems to have overtaken others, based on these points:

A. Gurdjieff claimed to be 78 years old in 1943, and 83 years old in 1949 (the year of his death).

B. The photos of him taken shortly before his death (in 1949) seem (to Moore) more like a man in his early 80s, rather than a man in his mid or early 70s.

C. Gurdjieff claimed that when he was a seven year old boy his father’s cattle herd was wiped out by a plague. There was in fact a disastrous outbreak of cattle disease (rinderpest) in 1872-73 in Asia Minor.

D. Gurdjieff and his family arrived in the Turkish city of Kars not long after a Tsarist military victory in 1877, at a time when Gurdjieff already had four younger siblings.

E. This point is not mentioned by Moore, but it is worth listing: when Ouspensky first met Gurdjieff in 1915 in Moscow, he described Gurdjieff as a man appearing “no longer young”. If Gurdjieff was born in 1877, he would have been 38 at the time of meeting Ouspensky; if born in 1872, then 43; and if born in 1866, he would have been 49. I think it safe to assume that “no longer young” fits more closely with 43 or 49 rather than 38. Ouspensky himself was 37 at the time of this meeting; it is unlikely he would describe someone around his own age as “no longer young.”

Gurdjieff did have a passport that gave his birth year as 1877, but as mentioned he had several passports, some with different dates—one indicated as early as 1864—and all of them he burned in 1930 before one of his trips to America. (see Patterson, Struggle of the Magicians, p. 216). While Moore’s points are interesting, they are not foolproof, and he does appear to make one mistake. The counter-views are as follows:

A. The fact that Gurdjieff claimed a certain age for himself means little, as he was commonly known to have no fear of saying whatever he felt like saying at any given time, regardless if it was based in fact or not. Moore’s first argument, that Gurdjieff claimed to be 78 in 1943, does not add up arithmetically—78 in 1943 would mean he was born in either 1864 or 1865, not 1866. And this appears to be Moore’s mistake, because he states that one passport of Gurdjieff’s listed his year of birth as the “wildly discrepant 1864”—when Gurdjieff himself apparently stipulated this year (or 1865) when describing his age in 1943. Further, according to J.G. Bennett in his autobiography, he reports that Gurdjieff in January of 1949 claimed that he was now 80 years old. That would make his birth year 1869, not 1866. Bennett indicates that he believed Gurdjieff was not telling the truth, that in fact he was “a good deal younger.” (See J.G. Bennett, Witness: The Autobiography of John Bennett (Wellingborough: Turnstone Press, 1983), p. 251.

B. The photos of Gurdjieff supposedly looking 83 years old could easily be pictures of a 72 or 77 year old man who had lived a very rugged life (which was certainly true in Gurdjieff’s case). This was further suggested by the doctor who performed the autopsy on Gurdjieff’s body, declaring that he should have died years before as most of his organs were in very poor shape.

C. Some video of Gurdjieff surfaced in the early 2000s on the Internet—mostly short silent clips of him interacting with students in public places during the last years of his life (1947-49). Examining those videos it is surprising to think that the short, portly man (as he was at the time) is in his early 80s. Very few overweight people live into their 80s. He moves around in a fairly nimble fashion that seems a bit quick for an 82 or 83 year old. (But he was, after all, a “teacher of dance” as he liked to describe himself, and was clearly a very rugged man, so it is not impossible).

J.G. Bennett favored 1872. In his book Gurdjieff: A Very Great Enigma, he wrote:

So far as I myself can make out from various sources, from what he himself and his family have told us, it does seem probable that he was born in 1872, in Alexandropol, and that his father moved to Kars soon after it was taken by the Russians, that is to say, somewhere about 1878, when he was six or so years old. (Bennett, 1963).

About ten years after that Bennett wrote his loose biography of Gurdjieff (Gurdjieff: Making a New World) and had this to say:

The date of Gurdjieff’s birth, as shown on his passport, was December 28th, 1877. He himself said he was much older and also claimed that he was born on January 1st old style. I have found it hard to reconcile the chronology of his life with the date of 1877, but his family asserts that this is correct. If this is so, he began his search at the early age of eleven, because he refers to the year 1888 as a time when new vistas opened up to him. He first went to Constantinople in 1891. He says he was a “lad” at the time of this journey, so the dating is not obviously inconsistent. Nevertheless it does seem strange that, if he was born in 1877, he should not have mentioned that this occurred during the Russo-Turkish war. (Bennett, 1973).

Despite these misgivings, Bennett goes on to state:

In October of 1877, the city [of Kars] was in its last throes, and the tsar sent his brother, Grand Duke Nicholas, to lead the final assault. With an overwhelming superiority in numbers and armaments, the defenses were overrun on the night of November 17-18. Six weeks later, Gurdjieff was born in Gumru, already renamed Alexandropol in honor of the tsar’s father. (Bennett, 1973).

So apparently Bennett either forgot that a decade before he’d declared Gurdjieff’s probable year of birth as 1872, or he changed his view. Jeanne de Salzmann, Gurdjieff’s chief administrator and designated leader of the world-wide Gurdjieff community at his death in 1949, held to 1877.

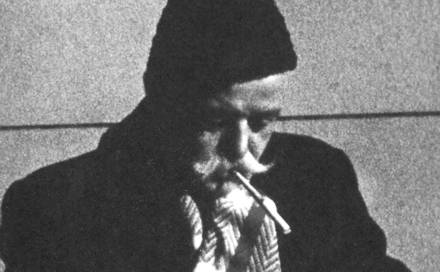

All this is contradicted yet again in another of Bennett’s books, his 1961 autobiography (Witness: The Autobiography of John Bennett), where he writes of his first meeting with Gurdjieff in 1920:

It was only when he removed his kalpak after the meal that I saw his head was shaved. He was short but very powerfully built. I guessed that he was about fifty, but Mrs. Beaumont was sure that he was older. He told me later that he was born in 1866, but his own sister disputed this and affirmed that he was born in 1877. His age was as much as an enigma as everything else about him. (Bennett, 1961, p. 55).

That particular anecdote does not bode well for the 1866 date, as a man’s sister would generally have little incentive for lying about such a thing, nor would she be likely to make such a large error as eleven years when estimating her older brother’s age. (Although it is conceivable, if she was incompetent with arithmetic—i.e., an honest mistake).

Finally, it bears mentioning here that one of the better more recent chroniclers of Gurdjieff and his Work, William Patrick Patterson (who has written several books and produced three good videos on the matter), weighs in with his vote for 1872. In the notes section of his Struggle of the Magicians, he remarks:

I believe that Gurdjieff was born—not in 1877 nor in 1866—but in 1872. This is based on dates Gurdjieff gives in Meetings with Remarkable Men. (Patterson, 1996).

He then goes on to provide a series of arguments based on events in Meetings that easily counters Moore’s arguments for 1866. Amusingly, he also notes that Olga de Hartmann, a close student of Gurdjieff’s, always believed that he was older than the 1877 date, but was unable to prove it—despite the fact that her own passport listed her year of birth as 1896 when in fact she was born in 1885. At any rate, to me the most logical date does indeed seem to be something closer to 1872, particularly judging from the video clips taken of Gurdjieff’s last years. Bennett, though originally promoting this year, gives no real argument for it. Patterson (for 1872) and Moore (for 1866) seem to be the only researchers who provide solid arguments for their dates.

5. G.I. Gurdjieff, Meetings with Remarkable Men (London: Routledge Kegan Paul, 1963). Most recent reprint is by Penguin Compass, 2002.

6. For an interesting take on a possible connection between Gurdjieff’s ideas and Castaneda’s, see William Patrick Patterson, The Life and Teachings of Carlos Castaneda (Fairfax: Arete Communications, 2008).

7. Gurdjieff, Meetings, pp. 89-91.

8. Ibid., p. 99.

9. Ibid., p. 119.

10. Ouspensky, In Search of the Miraculous, p. 302.

11. James Moore, Gurdjieff: Anatomy of a Myth (Rockport: Element Books, 1991), p. 216.

12. P.D. Ouspensky, Tertium Organum: A Key to the Enigmas of the World (London: Kegan Paul, Trench and Trubner & Co., 1922). Most recent reprint is by The Book Tree, 2004.

13. William Patrick Patterson, Struggle of the Magicians: Why Uspenskii Left Gurdjieff (Fairfax, Arete Communications, 1996), p. 94.

14. G.I. Gurdjieff, Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson (New York: Viking Arcana, 1992).

15. I myself can attest to the power of his idea of Objective Art, remembering my visits to sites such as the Taj Mahal, the Great Pyramid, the Sphinx, the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, Petra in Jordan, and the Gothic Cathedral of Palma de Mallorca. The sheer power of these architectural forms is obvious, and the response I had to them seemed in accordance with Gurdjieff’s teachings about the “higher emotional body.” I found this especially so with the Dome of the Rock; Islamic mosques seemed to be originally designed with the intention to draw one’s attention up toward the upper chakras of the subtle body.

16. www.gurdjieff.org/wright1.htm

17. John Carswell, Lives and Letters (New York: New Directions Books, 1978), p. 185.

copyright 2010, by P.T. Mistlberger and Axis Mundi Books.