The Solitary Retreat

by P.T. Mistlberger

(The following is an excerpt from my recent book Resilience: Going Within In a Time of Crisis, Changemakers Books, 2020).

The events of the global pandemic of 2020 have resulted in some extraordinary changes in many countries around the world, foremost of which, on the practical level, has been separation (distancing), and some degree of isolation. The lessons and challenges that go with this are more or less obvious and need not be repeated here. Need for proper self-care and clear communication with others is at a premium. But it is also natural in such circumstances for some to explore the idea of a retreat, either formally, or in a more casual fashion. Not all have the means or the desire to do such a thing, for sure. But for those that do, this is a good time. What follows here are some guidelines for undertaking a retreat, as well as remarks on a prolonged solitary retreat undertaken in Nature from a period of my past.

The Way of the Psychonaut

From May 20 to June 30 of 1988—a period spanning forty days and forty nights—I did an intensive solitary experiment that involved fasting, communing with Nature, extensive meditation, self-examination, dream-work, and trance-work. The retreat did not include any usage of entheogens or any other direct mind-altering substances. The first 10 days I fasted (juice and water for 3 days, water only for 6 days, and one ‘dry day’ with no food and no water). The last 30 days I took regular, though simple, meals. The retreat took place in an isolated cabin in the forests of the Coastal Mountains of British Columbia. This was an inner and outer operation that required significant commitment to complete.

My choice of a forty-day retreat was, at the time, based mainly on practical expediencies. It was the maximum amount of time I could take off from work. I was, many years later, intrigued to discover that the English word ‘quarantine’ derives from the Italian word quarantina, meaning ‘40 days’. During the mid-14th century, when the Black Death was ravaging parts the world and especially Europe, some sort of plan was implemented (in Croatia, initially) requiring visitors to be isolated for 30 days (‘trentine’) to see whether symptoms of the disease would show. In the 15th century, when periodic outbreaks occurred, it was first lengthened to 40 days in Venice, from whence arose the term ‘quarantine’.

The cabin I used belonged to a friend of mine with whom I’d arranged a barter with for usage of it. The cabin was situated in deep woods about two-thirds of the way up the south face of a mountain. The retreat had been undertaken under the loose guidance of a mentor I had briefly had at that time, a mystic who worked with trance-mediumship and related forms of shamanism. For my retreat he had suggested I be near either ocean or mountains. I opted for the latter, having always felt a kinship with mountains.

The cabin I used belonged to a friend of mine with whom I’d arranged a barter with for usage of it. The cabin was situated in deep woods about two-thirds of the way up the south face of a mountain. The retreat had been undertaken under the loose guidance of a mentor I had briefly had at that time, a mystic who worked with trance-mediumship and related forms of shamanism. For my retreat he had suggested I be near either ocean or mountains. I opted for the latter, having always felt a kinship with mountains.

A sustained retreat undertaken for inner work—whether that be called a meditation retreat, a vision quest, a magical retirement, or by any number of designations—is common to many wisdom traditions. Perhaps the most sustained and developed of these retreats are found in Asia, and in particular, in Tibetan Buddhism. That is natural, as the chilly plateaus north of the Himalayas, as well as the forbidding mountain ranges themselves, have long been thought of as sanctuaries to those more extreme seekers of inner truth sometimes known by the modern term ‘psychonaut’. I have spent time in Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, though perhaps ironically, my own deepest psychonautics experiences took place in my native Canada.

The word psychonaut—and the accompanying term psychonautics—stem from the Greek terms psyche (mind/soul/spirit) and nautes (navigator/sailor of the seas). Therefore, a psychonaut is technically a ‘navigator of the seas of the mind/soul/spirit’. Or more simply, a navigator of the inner worlds—standing polar opposite to the astronaut, who is the navigator of the outer stars (from ‘astra’, Greek for ‘stars’).

The prolonged spiritual retreat has not been limited to Tibetan traditions. Certain Christian hermitages have abounded with legends of cloistered monks and tales of the solitary Desert Fathers, along with Islamic (Sufi) mystics, Jewish renunciates, and Hindu sadhus who wander the land as mendicants, and other hermits devoted solely to inner practices. Also renowned is the North American Indian vision quest.

In the Western esoteric tradition, and especially within the area known loosely as ceremonial magic—doubtless one of the more obscure, least-known, and most irrationally feared pathways to self-knowledge—there exists the formidable practice known as the Abramelin Operation. This is a ‘magical retirement’ known mainly via the notorious book The Book of the Sacred Magic of Abramelin the Mage. This book, written in the 15th century by one Abraham of Worms (a town in central Germany), was first brought to public notice by Samuel MacGregor Mathers, one of the three founders of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. Mathers’ published a translation in 1900 of a French copy that specified the retreat as being 6 months long, although subsequent work by the German researcher Georg Dehn, working with older German manuscripts, established that the retreat specified by Abraham was in fact intended to be 18 months long.

In the Christian tradition, the ‘Temptation of Christ’ is a cornerstone of the legend of Jesus, based on his 40 days and nights in the desert, in which he is confronted by Satan, the great tester. What is less commonly known is that Elijah and Moses also undertook 40-day retreats. In all three cases, they fasted for the entire 40 days. That degree of effort was beyond my capacity and purpose—10 days of fasting, out of the 40 days of my retreat, was more than enough for me and about all I was willing to attempt.

The various categories of retreat, including the tradition most commonly associated with them—in increasing order of difficulty—look something like the following (of course, one could pick any random number of days; these are some of the most renowned).

- Three-day retreat (basic).

- Four-day vision quest (Native Amerindian). Best undertaken in Nature.

- Ten-day meditation retreat (Theravadin Buddhism, usually employing vipassana meditation).

- Three-week meditation retreat (Theravadin and Zen Buddhism).

- Forty-days retreat (tradition of Moses, Elijah, Jesus, and the Desert Fathers).

- Six-month retreat (Abramelin Operation, Mathers’ version).

- Eighteen-month retreat (Abramelin Operation, Dehn’s version).

- Three years and three-month retreat (Tibetan Buddhism).

- Ten-year retreat (Tibetan Buddhism).

The purpose of any retreat based on legitimate psycho-spiritual practices is to purify one’s mind and open it to, and align it with, its highest potentials. These ‘highest potentials’ are typically defined in transcendent terms, because they are deeply intangible, and thoroughly experiential. Words may be recorded (or situations filmed on your smartphone), but nothing substitutes for the direct experience. To cite the old Zen analogy, words or images are ‘fingers pointing toward the Moon’, with the Moon representing, in this metaphor, the unqualified, undefinable isness of consciousness and presence.

A basic recommendation of any sort of retreat is to keep a journal or diary of it. In my case, I kept detailed notes, scrawled in pencil in two simple notebooks. When I began the retreat I intentionally brought no timepieces or calendars with me. Each day I never knew what time it was and the only way I knew what day it was, was by my journal entries. And even then, I lost track once or twice.

A basic recommendation of any sort of retreat is to keep a journal or diary of it. In my case, I kept detailed notes, scrawled in pencil in two simple notebooks. When I began the retreat I intentionally brought no timepieces or calendars with me. Each day I never knew what time it was and the only way I knew what day it was, was by my journal entries. And even then, I lost track once or twice.

The retreat was a focused experiment intended to tap deeply into the unconscious mind, and in so doing, to experience the subtle, transpersonal realms of spirit. For this, I had to find ways to selectively disengage the conscious intellect. Bringing no timepieces or communication devices of any sort was part of that. Yes, cellphones—though primitive versions of them—did exist back in 1988. Like most people then I did not own one. The times we inhabit now are very different, in that it is more difficult to disengage from our network of contacts. In current times, should one take a cell phone to a lengthy retreat, especially in Nature? The answer is yes, for safety purposes. However, the idea is not to use it unless absolutely necessary! That requires significant discipline.

Disengaging the conscious intellect for an extended period is hard work. As it happened, when I was in the cabin I found a cheap paperback on the history of Western philosophy, which was comfort food for my complaining intellect. I indulged myself for a few afternoons of the retreat and read the book. Aside from that, I stayed with the program, which consisted of the following:

1. Six to eight hours daily of sitting meditation. This included various forms of trance-induction work, both waking and hypnagogic, alongside classic forms of witnessing meditations such as vipassana and Zen koan work, and invocations of higher mind (or ‘holy guardian angel’, to use the Western esoteric term).

2. Daily strenuous hikes in the forests of the local mountains, including at night with no flashlight. This included scaling a nearby mountain, a modest 4,000-foot peak, and extended meditation on its summit (which was cool and still snow-encrusted even in June).

3. Daily journaling, recording in detail experiences in meditation, hikes, and nightly dreams.

4. Art therapy as a means to connect with both archetypal and personal ancestral spirits. Each day I drew extensive colored images of faces that would arise in my mind during the meditations. (Art is a very potent and underrated method for accessing the unconscious, as it works via visual symbols, the language of the unconscious).

5. Diet, which was basic, free of meat and sugar, but enough to keep my energy up.

6. Strenuous manual labor, such as digging ditches.

The month-long retreat, though mainly concerned with the inner world, was punctuated by a few memorable outer events. These included being confronted by a vicious stray dog (I was not injured) and getting lost in the forest on one of my night hikes. The latter was indeed memorable. I never understood prior to then just how dark a mountain forest becomes in the dead of night. As much as my human eyes struggled to adjust (and I had flawless vision then), I could barely see my own hands in front of me. I recall I had to get down on the ground and crawl my way through the forest in order to orient myself. I eventually emerged into a dried-up creek and was able to trace that route back to the cabin. I arrived back at what I estimated to be around 3am. I could not sleep, so energized was I by the ordeal. My entire body-mind was on fire, doubtless the effect of adrenaline flooding the body in the face of what my mind judged to be a significant threat to survival.

The month-long retreat, though mainly concerned with the inner world, was punctuated by a few memorable outer events. These included being confronted by a vicious stray dog (I was not injured) and getting lost in the forest on one of my night hikes. The latter was indeed memorable. I never understood prior to then just how dark a mountain forest becomes in the dead of night. As much as my human eyes struggled to adjust (and I had flawless vision then), I could barely see my own hands in front of me. I recall I had to get down on the ground and crawl my way through the forest in order to orient myself. I eventually emerged into a dried-up creek and was able to trace that route back to the cabin. I arrived back at what I estimated to be around 3am. I could not sleep, so energized was I by the ordeal. My entire body-mind was on fire, doubtless the effect of adrenaline flooding the body in the face of what my mind judged to be a significant threat to survival.

More than one person has gotten lost in the wilds before, never to be seen again. David Paulides, in his compelling (and controversial) ‘411-Missing’ books, documents hundreds of unsolved cases in North American national parks alone over recent decades. The reason it is so easy to become disoriented in a forest is because nothing is symmetrical, unlike our largely symmetrical towns and streets. A forest is shrouded, organized chaos. It is easy in a darkened forest to not realize that you have circled back to where you started, and therefore not really gone anywhere (a theme well portrayed in the classic campy 1999 horror flick The Blair Witch Project).

In addition to the physical adventures, I also experienced a deep sense of connection with what I can only categorize as ancestral spirits. Part of this was connected to an assignment I had been given by my shaman-mentor to draw faces that would appear in my mind in my meditations. This in turn seemed to form a kind of link to the personality, which in turn opened the door for a connection that I can only describe as ultimately healing.

However, not all such experiences were pleasant. On one occasion—in a dream state, I emphasize—I was ‘visited’ by a mechanical-type creature who pressed painfully on my lower back, and then suddenly whisked me away to a spacecraft that was orbiting Earth. On this craft I was ushered down some hallways into a strange room. It was a generally unpleasant experience. After a hiatus I eventually found myself back on the couch in the cabin, with a weird buzzing sound around me and a strange metallic taste in my mouth. Over the next few minutes, I came fully back into my body. Strange experiences such as these, which become easier to experience during prolonged isolation in Nature, make it clear that psychoactives are not needed if the discipline of meditation is applied, along with the luxury of sufficient time to go deep.

Other equally bizarre paranormal and mystical experiences visited me during my time in the cabin. Much of this was accompanied by periods of deep emotional purging. In some ways it was like being turned inside out. The force that drove these experiences was the outer and inner quiet I was entering. The forest is not a particularly quiet place, especially in June, when all sorts of creatures are stirring about. But as my mind became increasingly quiet, I began to tune into the natural silence all around me. The forest was buzzing with life, but it was also strangely silent at the same time, utterly free of the constant psychic-chatter of human society. After a while, I began to realize where the silence was coming from. It was simply part of Nature, but it was also the natural state of the mind when free of distractions, and when the flow of thought has been slowed down sufficiently via disciplined daily meditation.

Other equally bizarre paranormal and mystical experiences visited me during my time in the cabin. Much of this was accompanied by periods of deep emotional purging. In some ways it was like being turned inside out. The force that drove these experiences was the outer and inner quiet I was entering. The forest is not a particularly quiet place, especially in June, when all sorts of creatures are stirring about. But as my mind became increasingly quiet, I began to tune into the natural silence all around me. The forest was buzzing with life, but it was also strangely silent at the same time, utterly free of the constant psychic-chatter of human society. After a while, I began to realize where the silence was coming from. It was simply part of Nature, but it was also the natural state of the mind when free of distractions, and when the flow of thought has been slowed down sufficiently via disciplined daily meditation.

It can be surprisingly hard to commit to, let alone organize, an extended retreat. What follows are some of the most common roadblocks.

Impediments to Retreat: Survival, Fear, Lack of Desire for Truth

Survival. Undertaking a significant retreat usually requires considerable practical planning. It can be surprisingly complicated to arrange. This is one of the reasons why such retreats—especially for those longer than two weeks—are often easier to undertake when under the age of 30, or over the age of 60. The years of adulthood from approximately 30 to 60 are generally the busiest years, in which our lives are more complicated, weighed down by entanglements, obligations, and responsibilities difficult to get away from.

Fear. The word ‘fear’ is left alone and generic here, as it can apply in many directions. The most common fear is in the psychological category, and basically reduces to the fear of being alone. For retreats in wilderness or general nature locations, this fear can be enhanced. It may also involve fears of disappearing or dying without being noticed or found. These fears can be reduced to core-beliefs of personal unworthiness or unimportance or inherent unlovableness.

Lack of Desire to Go Deep. This is perhaps the most significant barrier, because if the longing for deeper truths is not there, then the motivation for tackling the two impediments above will not be there either. Essentially, the desire for truth—or, put alternatively, the love of truth—has to overcome the psychological fears and practical obstacles.

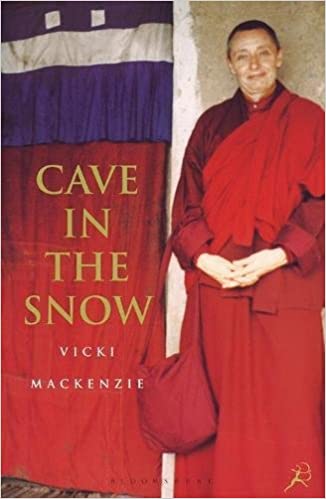

There are of course many examples of mystics who have undertaken lengthy retreats, from the time-honored classic stories of the Buddha (his six years in the forest, though he did consort with various teachers and yogis during that time), Jesus, Milarepa, and Ramana Maharshi. Perhaps one of the more remarkable, and well documented, more recent examples is that of Tenzin Palmo (born Diane Perry in 1943), an English ordained Tibetan Buddhist nun who was subject of Vickie Mackenzie’s book Cave in the Snow: A Woman’s Quest for Enlightenment. Her example is extraordinary because she spent twelve years in a remote Himalayan cave, three of which were spent in meditative isolation. During those three years she grew her own food and only slept three hours a night while sitting upright in a wooden box.

There are of course many examples of mystics who have undertaken lengthy retreats, from the time-honored classic stories of the Buddha (his six years in the forest, though he did consort with various teachers and yogis during that time), Jesus, Milarepa, and Ramana Maharshi. Perhaps one of the more remarkable, and well documented, more recent examples is that of Tenzin Palmo (born Diane Perry in 1943), an English ordained Tibetan Buddhist nun who was subject of Vickie Mackenzie’s book Cave in the Snow: A Woman’s Quest for Enlightenment. Her example is extraordinary because she spent twelve years in a remote Himalayan cave, three of which were spent in meditative isolation. During those three years she grew her own food and only slept three hours a night while sitting upright in a wooden box.

Such feats of discipline are beyond most people, and rarely necessary. But the power of extended time in solitude, and especially in Nature, can never be underestimated. My own retreat had a specific focus, that of aligning with my higher nature, while at the same time facing the demons within—those buried in my subconscious, those that are echoes of my family tree and its history, and those of deeper karmic tendencies. In my own case, my 40 days culminated in a spectacular experience of ecstasy as I established communication with a ‘spiritual force’ that I can only, to this day over three decades later, regard as transcendent. The communion with this ‘force’, utterly independent from my ego-mind, was extraordinarily real, as real as the keyboard upon which I type. That said, the main point I stress here is that an extended retreat of any sort—be it for 6 months or 6 weeks or 48 hours—will result in some sort of direct insight into the deeper recesses of one’s being, provided one truly commits to the process. In longer retreats, this direct insight very commonly manifests in some extraordinary ways.

The above describes a fairly ambitious retreat, that in my case was, in the end, very much worth it. For most people, a shorter retreat is both more practical and all that is needed. Here are some general guidelines for a 3-day retreat:

1. No communicating with anyone. This is important. Best is to leave aside your phone for the three days. If you have it on you, try to keep it shut off the whole time. Avoid checking social networking, etc. Tell someone close to you, like a family member, where exactly you’ll be, and that you’ll be out of touch for three days.

2. Writing is okay, reading is not recommended. Journal out your thoughts.

3. Keep a dream diary.

4. Artwork. Take some paper and colored pencils or markers and draw images that come to your mind in meditation.

5. Meditate daily. Perform growth rituals if familiar with them (High Magic, Tai Chi, Qi Gong, etc.).

6. Juice fasting is best. If you do eat, keep it very light.

7. Don't oversleep. It’s not supposed to be a hibernation, but rather a wakeful retreat.

8. Exercising. In some retreats, you stay indoors, so obviously this exercising has to be constrained by that. Pushups, sit-ups, jogging on the spot, or simply a long walk outside in the early morning is ideal.

Addendum: It is common, when alone in Nature, to feel kinship with not just human ancestors, but animal spirits as well. A personal 'protector spirit' of mine I have long identified as the black wolf. I am reminded here of a short story written by Scot Casey in the 1980s, in which he describes a solo adventure in the woods where he comes upon a stray dog, while heading back to his cabin. He encourages the dog to follow him, figuring that he will take care of the poor beast, feed him, and perhaps adopt him. After the long hike back to his cabin is nearly over, the dog, trotting about 50 feet behind him, suddenly stops. Casey imagined, for a moment, that the dog was transmitting a telepathic message. The message was, "I don't need you to take care of me. I was only following to make sure that you got back to your cabin safely." And with that, Casey wrote, the dog smiled at him, lowered its head, and trotted away.

Addendum: It is common, when alone in Nature, to feel kinship with not just human ancestors, but animal spirits as well. A personal 'protector spirit' of mine I have long identified as the black wolf. I am reminded here of a short story written by Scot Casey in the 1980s, in which he describes a solo adventure in the woods where he comes upon a stray dog, while heading back to his cabin. He encourages the dog to follow him, figuring that he will take care of the poor beast, feed him, and perhaps adopt him. After the long hike back to his cabin is nearly over, the dog, trotting about 50 feet behind him, suddenly stops. Casey imagined, for a moment, that the dog was transmitting a telepathic message. The message was, "I don't need you to take care of me. I was only following to make sure that you got back to your cabin safely." And with that, Casey wrote, the dog smiled at him, lowered its head, and trotted away.

The moral being, in committing deeply to something, such as a solitary retreat, more often than not we find that our fears are transformed and that untapped forces are present, watching out for us, having our back. Not always, for sure, as the universe is vastly mysterious and outcomes can never be fully predicted. But one thing is certain, and that is that we are never really alone.

Copyright 2020 by P.T. Mistlberger and Changemakers Books, all rights reserved.