A life-long interest of mine has been the ‘royal game’, chess. I played my first game as a boy sometime in the 1960s; my parents had a set and used to play the odd game. But it was in the summer of 1976 when I was 17 years old that my interest in the game caught fire. It began with a casual game against my brother, played on a board that we drew on a piece of paper (apparently we had pieces at that point, but no board).

Sometime after that I discovered the Canadian chessmaster Lawrence Day’s chess column in the Montreal Star newspaper. Intrigued by Day’s annotations, I taught myself how to read chess notation, and proceeded to replay the game he’d printed in his column that week. Not long after that I had my hands on my first chess book and was replaying games as a way of teaching myself the basic elements. I recall having a month off that summer, on break from school and work, during which time I discovered the Café En Passant on St. Denis street in Montreal. This was both a good and bad thing. Good because the café was a chess player’s delight: a smokey den of iniquity, featuring mediocre lighting, rickety tables, and giant sandwiches served by a cheerful but hopelessly underworked server (chessplayers rarely eat when playing, so engrossed are they in the mystical combinations before them). The joint was invariably crowded with all kinds of players. You could always just go there and get a game, and often strong masters would be present. More than once I rubbed shoulders with the likes of Peter Biyiasis and Kevin Spraggett, both top Canadian players; the former a grandmaster and the Canadian champion at the time, the latter a future grandmaster, future Canadian champion and future world champion contender.

The Cafe En Passant was also a bad place to be because this was the site of my growing addiction to the Royal Game, an addiction that was so strong that for several months, when I should have been at school or studying during my first semester of college, I was spending most days at the café, playing chess from morning till night. This ‘den’ was truly an intellectual’s opium den. That the ‘drug’ was a 64-square board and 32 cheap Staunton-pieces, not a white powder, was secondary. The addiction was arguably as strong.

There are thousands upon thousands of chess books out there, but the vast majority are technical manuals, concerned with training or analyzing the details of particular games (usually those of the world elite, grandmasters and international masters). These books are utterly incomprehensible and dull to all but serious students of the game. Occasionally a rare book comes along that actually writes about chess from the perspective of the one interested in the psychology of the game. An example was Idle Passion: Chess and the Dance of Death, written by Alexander Cockburn and published in 1975. The author took a dim, Freudian view of the game, one not appreciated by devoted players (his basic premise is that chess is an Oedipal game, based on a deep-seated desire to kill the father, the king, with the aid of the mother, the queen, the most powerful piece). A more sympathetic appraisal of the game, but complete with enough insider’s lore to satisfy the biggest chess nerd, is Paul Hoffman’s King’s Gambit: A Son, a Father, and the World’s Most Dangerous Game (2007).

Chess is, of course, much more than a mere ‘game’. It is a type of ‘legominism’, Gurdjieff’s term for a teaching of vast wisdom that is encoded into an apparently ‘mundane’ form, but which in fact contains deep knowledge of matters far transcending its gaming level. (Gurdjieff gave further examples of ‘legominisms’ as the Great Pyramid-Sphinx complex at Giza, and the Tarot—both other favourite areas of study of mine that I will expand on in this website as time permits). Chess history is full of endlessly fascinating lore and naturally opens one up to such matters as pure history, mysticism, psychology, anthropology, and science.

My serious chess playing days lasted for three and a half years, from 1976 to 1979, when I played in my last tournament. During that span I competed in dozens of speed chess tournaments at the Alekhine chess club in Montreal, as well as perhaps ten standard tournaments. My big success was in winning the Quebec intercollegiate championship in 1979.

Owing to focus on other areas (academia, and then an intensive spiritual search) throughout the 1980s I played very little chess; I recall a few games in Nepal during my visit there in early 1986. It was only in the 1990s that I began playing regularly again when I first got Internet access. Chess has remained a lifelong interest, although my skill level has increased only marginally since I stopped playing serious over-the-board tournament chess over thirty years ago.

Below are a couple of tournament games I played against the old master Ignas Zalys in 1978. Zalys had emigrated from the Soviet Union to Canada shortly after WWII. In his heydey he was a strong master, having won the Montreal closed championship, and the Quebec open championship three times. He'd also notched victories over world class players like Browne and Spraggett. He'd even played against former world champion Boris Spassky, losing the following game against the great grandmaster in a respectable fashion:

http://www.newinchess.com/NICBase/Default.aspx?GameID=1445952

In addition to his tournament successes, Zalys had other claims to fame, including a victory over the legendary Bobby Fischer when the latter gave a simul in Montreal in 1964:

http://www.chessgames.com/perl/chessgame?gid=1378800

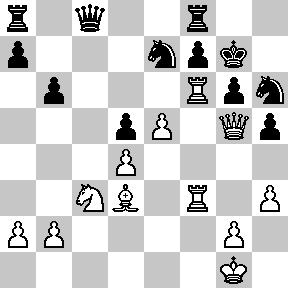

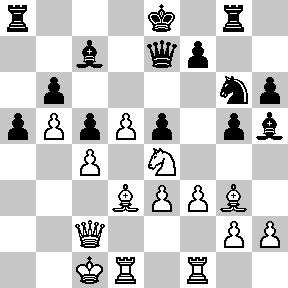

Almost half a century separated us by the time I played him in 1978; he the old master in his late 60s, me, the nineteen year-old ‘class A’ acolyte. The first game he whipped me in 31 moves; I managed to win the second in 36 moves.

1. e4 c5 2. c3 g6 3. d4 cxd4 4. cxd4 Bg7 5. Nc3 d6 6. Nf3 Bg4 7. Bc4 e6 8. Be3 Qb6? 9. Bb5+ Kf8 10. O-O Bh6 11. Qd2 Bxe3 12. fxe3 Bxf3 13. Rxf3 Kg7 14. Qf2 Nh6 15. Rf1 Rf8 16. Rh3 Qd8 17. Qf4 Ng8 18. e5 d5 19. e4 Nc6 20. exd5 exd5 21. Na4 Nce7 22. Bd3 b6 23. Qh4 h6 24. Rf6 Qd7 25. Nc3 h5 26. Qg5 Qg4 27. Qe3 Nh6 28. Rhf3 Kh7 29. h3 Qc8 30. Qg5 Kg7

31. Nxd5! 1-0 (Here I resigned because if 31...Nxd5, then 32. Rxg6+, fxg6 33. Qxg6+ followed by Qh7 mate.

1. d4 Nf6 2. c4 e6 3. Nc3 Bb4 4. Bg5 h6 5. Bh4 c5 6. d5 d6 7. e3 e5 8. Qc2 Nbd7 9. Nge2 g5 10. Bg3 Nf8 11. a3 Ba5 12. b4 Bc7 13. Nc1 b6 14. Bd3 Rg8 15. N1e2 Ng6 16. O-O-O? (unnecessarily risky, and probably squandering any advantage) cxb4 17. axb4 a5 18. b5 Nd7 19. Na4 Qf6 20. Rhf1 Nc5 21. Nxc5 dxc5? (he had to take with the other pawn) 22. Nc3 Bg4 23. f3 Bh5? (the black bishop is now entombed, and White essentially has a won game) 24. Ne4 Qe7

25. d6! Bxd6 26. Nxd6+ Qxd6 27. Be4 Qb8 28. Bxa8 Qxa8 29. Rd6 Kf8 30. Rfd1 Kg7 31. Qf5 Re8 32. Qf6+ Kg8 33. Rd7 Nf8 34. Rd8 Rxd8 35. Rxd8 Qb7 36. Bxe5 and with mate next move, Zalys calls it a day. 1-0

Back

in my tournament-playing days the chess giants were figures like

Karpov, Korchnoi, Tal, Larsen, and so forth. Kasparov, probably the

greatest player ever, was just around the corner, coming to prominence

in the ‘80s via his epic struggles against Karpov, in which Kasparov

dethroned the inscrutable Soviet. In 1979 I attended the famous Montreal

‘Tournament of Stars’. This was a momentous event, a tournament of

unheard of strength at the time, in which the strongest grandmasters in

the world, with the exception of Fischer (then in self-imposed exile)

and Korchnoi, participated. Present were world champion Karpov, Tal,

Larsen, Spassky, Hort, Portisch, Hubner, Kavalek, Timman, and

Ljubojevic. The event was won by Karpov and Tal, both with 12 pts.

(Karpov +7-1=10, Tal +6-0=12).

On

the face of it chess is pure triviality, an exercise in conceptual

focus that, while extraordinarily deep in complexity (some mathematician

once determined that there are more possible chess games than number of

atoms in the universe), is hopelessly limited in scope. It is, after

all, a game. But like Hesse’s ‘Glass Bead Game’, as described in his

novel Magister Ludi, it is in

fact a doorway to much more, even if it is almost never used in such a

way. The key to Hesse’s game was association between multiple

disciplines of learning. Chess is a similar vehicle, that if approached

from the point of view of one seeking a doorway into the mysteries of

association (how ‘things’ relate), can become a vehicle for gaining vast

wisdom.

****

My father is a skilled (and rather prolific) artist. Below is some of his work. If interested, contact me for more info.