A Brief History of Witchcraft

Sex, Lies, and the Devil

by P.T. Mistlberger

All witchcraft comes from carnal lust, which is in women insatiable.

—Malleus Maleficarum (‘Hammer of the Witches’; published in 1487).1

As to what exactly a ‘Witch’ is, or what the word implies, there are a broad range of views; indeed, the word is probably one of the most loaded in the English language. This essay is not, however, a study of Witches or Witchcraft as a bona fide spiritual tradition (which it certainly is, at least in modern times),2 but is rather an examination of the Church’s persecution of ‘Witches’ and ‘Witchcraft’ during a gruesome phase of European history generally known as the ‘Burning Times’ (roughly from the mid-15th to the mid-18th century). This study is undertaken to understand more clearly the psychodynamics of the relationship between Church and Witchcraft, and between Inquisitor/priest/accuser and ‘Witch’. Further and arguably more important relationship dynamics, those of between Church and Satan, and Church and women, are also looked at.

The

word ‘Witch’, when used herein, is often presented in

quotation marks as scholarly research has demonstrated that many of

those tried and executed, though convicted of being Witches, were not in

fact that; there is a valid argument that a majority of them were everyday Christians who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong

time. That all of them, Witches or non-Witches, were falsely convicted,

or at the least unjustly tried, certainly by modern judicial standards,

is more or less accepted at face value here.

The

word ‘Witch’, when used herein, is often presented in

quotation marks as scholarly research has demonstrated that many of

those tried and executed, though convicted of being Witches, were not in

fact that; there is a valid argument that a majority of them were everyday Christians who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong

time. That all of them, Witches or non-Witches, were falsely convicted,

or at the least unjustly tried, certainly by modern judicial standards,

is more or less accepted at face value here.

According to the Oxford Concise Dictionary of English Etymology (1993 edition) the word ‘Witch’ derives from the Old English terms wicca (a male sorcerer or wizard) and wicce (a female sorcerer or wizard). These were related to the Old English terms wiccian, meaning to ‘practice magical arts’, and wiccecraeft (Witchcraft). The terms wicca or wicce are sometimes believed to derive from an older word meaning ‘wise’, although in fact it is the word ‘wizard’ that derives from the Old English wiseard (‘wise one’).3 The word wicce is believed by most linguist scholars to derive from the term ‘bend’ or ‘twist’. Some modern Pagans re-interpret this as a witch’s ‘shamanic ability’ to bend or twist reality,4 perhaps something along the lines of Dion Fortune’s definition of magic: ‘the act of causing changes in consciousness to occur in conformity with will.’ This interpretation, though reasonable, appears to be a modern contrivance.

Modern Witchcraft, or ‘Wicca’ as it is now more commonly called by its practitioners, has a clear recent history that can at least be traced back to the publication of Gerald Gardner’s Witchcraft Today (1954), and more significantly, to the Egyptologist and anthropologist Margaret Murray’s controversial landmark work The Witch-cult in Western Europe (1921). Beyond that the historical roots are obscure, and a subject of great debate amongst many. Indeed the ‘history of the attempted history’ of Witchcraft is almost as interesting as any consideration of its actual roots.

The Roots of Persecution

Before considering the more recent and known history of Witchcraft, and especially the Witch-craze persecutions of the 15th through 18th centuries, it helps to have some understanding of the roots of the conflict between Church and Witchcraft. Most believe this to begin with the infamous line from the Old Testament (Exodus, 22:18): Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live (King James Version). However, modern adherents of Neo-Pagan faiths sometimes forget that the word ‘Witch’ in current times implies something very different (at least for Pagans and other sympathizers) than it did in 1611 when the KJV Bible was produced, and more to the point, back when Exodus was written.

The Old Testament, of course, was not written in English, but Hebrew. Exodus 22:18 in Hebrew reads (transliterated with vowels), M'khashephah lo tichayyah. This means, essentially, ‘you will not allow a khashephah to live.’ A khashephah is a ‘spell-caster’; a more currently accurate English term for it is probably ‘sorcerer’ or ‘sorceress’. The ‘spell-caster’ referred to in the writing of Exodus was a hostile spell-caster, not the benign Goddess or Nature-worshipper of Neo-Pagan traditions. (And indeed, some recent editions of the Bible have replaced the Exodus 22:18 word ‘Witch’ with ‘sorceress’.) In older times, such malefic spell-casters were common, and found in many cultures (just as they are today, particularly in African or Caribbean nations). Just as commonly, their power was believed to be real and they were often hunted down.5 Contrary to some popular views, the practice of Witch-hunting, while largely eradicated from Western Europe by the late 18th century, still crops up occasionally in the world. As recently as 2008 eleven people in Kenya were accused of Witchcraft and burnt to death,6 and in Papua New Guinea, the execution of witches, often via burnings, is still done on occasion up to current times.7

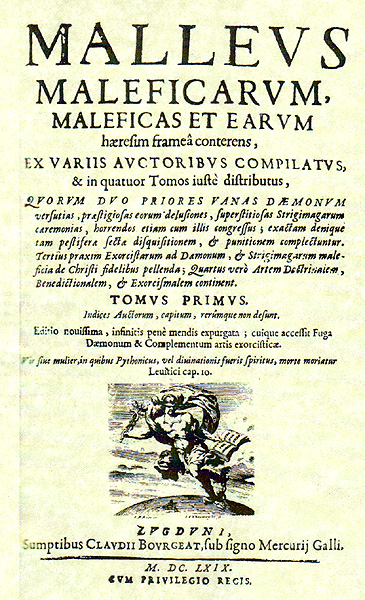

The origin of the persecutions of Witches on a mass scale that began in the early 14th

century in Europe appears to be, at first glance, a study of chiefly

two phenomena: misogyny, and ‘magical thinking’. The first, hatred of

women (deriving, presumably, from fear of them) was clearly one

of the main underlying themes of the infamous polemic published in 1487

by two Dominicans, the German Inquisitor Heinrich Kramer and the Swiss

priest Jacob Sprenger, called the Malleus Maleficarum (‘Hammer of

the Witches’). The book was commissioned by Pope Innocent VIII via his

1484 papal bull, and was heavily influential, going through dozens of

editions, the last as recent as 1669.8 It is a lurid manual

of instruction for would-be Witch hunters, describing Witches and their

way of life, including vivid depictions of their ‘sabbats’ with the

Devil, and how they are to be dealt with. It contains more than its

share of sweeping critiques and condemnation of women in general,

concluding that women are easier prey for Satan because they are weaker

both intellectually and physically, more credulous, and more prone to

gossip (thus naturally recruiting others into their ‘wickedness’).

The origin of the persecutions of Witches on a mass scale that began in the early 14th

century in Europe appears to be, at first glance, a study of chiefly

two phenomena: misogyny, and ‘magical thinking’. The first, hatred of

women (deriving, presumably, from fear of them) was clearly one

of the main underlying themes of the infamous polemic published in 1487

by two Dominicans, the German Inquisitor Heinrich Kramer and the Swiss

priest Jacob Sprenger, called the Malleus Maleficarum (‘Hammer of

the Witches’). The book was commissioned by Pope Innocent VIII via his

1484 papal bull, and was heavily influential, going through dozens of

editions, the last as recent as 1669.8 It is a lurid manual

of instruction for would-be Witch hunters, describing Witches and their

way of life, including vivid depictions of their ‘sabbats’ with the

Devil, and how they are to be dealt with. It contains more than its

share of sweeping critiques and condemnation of women in general,

concluding that women are easier prey for Satan because they are weaker

both intellectually and physically, more credulous, and more prone to

gossip (thus naturally recruiting others into their ‘wickedness’).

The persecution of ‘heretics’ did not begin with 15th century witches, however; it had earlier roots, most notably with the Cathars, a large and powerful semi-Gnostic sect that was persecuted by Pope Innocent III, culminating in the Albigensian Crusade of 1209-29 in which tens of thousands of Cathars (including women and children), most in southeastern France, were massacred. From the ashes of this Crusade was born the ‘Holy Office of the Papal Inquisition’, initiated by Pope Gregory IX in 1239. The job of this Inquisition was to suppress heretics. (The word ‘heresy’ derives from the Greek hairetikos, meaning ‘able to choose’—a disturbing reminder of the Church’s powers at that time to limit free will, or at the least, make attempts to exercise it in the realm of ideas, dangerous). The destruction of the Cathars was followed by the persecution and destruction (in 1312) of the Knights Templar, the powerful (though ultimately corrupt) Christian military order suspected of heretical beliefs. It had been just prior to that, in 1252, that Pope Innocent IV issued a papal bull authorizing torture as an Inquisitional tool (which some Knights Templar were subjected to), although in general, torture was not seriously and regularly used until the beginning of the Witch persecutions in the late 15th century. (Torture did, however, remain outlawed in some countries, like England).

The main job of the Malleus Maleficarum was to refute arguments that Witches did not exist, and as mentioned, to petition the case for women being the main spawns of the Devil. Rossell Hope Robbins called the book, ‘The most important and most sinister work on demonology ever written…opening the floodgates to the inquisitorial hysteria.’9 The misogyny in the text is almost overwhelming, making any male philosophers throughout history who have been critical of the female mind (and there have been many) seem like feminists. This extract from the text is as good as any:

What else is woman but a foe to friendship, an unescapable punishment, a necessary evil, a natural temptation, a desirable calamity, a domestic danger, a delectable detriment, an evil of nature, painted with fair colours! Therefore if it be a sin to divorce her when she ought to be kept, it is indeed a necessary torture; for either we commit adultery by divorcing her, or we must endure daily strife. Cicero in his second book of The Rhetorics says: The many lusts of men lead them into one sin, but the lust of women leads them into all sins; for the root of all woman’s vices is avarice. And Seneca says in his Tragedies: A woman either loves or hates; there is no third grade. And the tears of woman are a deception, for they may spring from true grief, or they may be a snare. When a woman thinks alone, she thinks evil… but because in these times this perfidy is more often found in women than in men, as we learn by actual experience, if anyone is curious as to the reason, we may add to what has already been said the following: that since they are feebler both in mind and body, it is not surprising that they should come more under the spell of witchcraft.10

And so on. Although it should be noted that while upward of 80% of tried and condemned Witches in Western Europe were women (and often women over the age of 50), this was not the case in some Scandinavian countries, where a majority of those persecuted and killed were men.

Added to the issue of misogyny, was that of ‘magical thinking’. By this is not meant some esoteric or occult art, but rather a specific type of faulty thinking known in logic as the post-hoc fallacy. This is a confusing of causal linkages of events—in this case, the observation that event A comes before event B, therefore event A must be the cause of event B. The following small example sheds immediate light on the potential dangers of this kind of thinking:

A woman in Scotland is burned as a witch for stroking a cat at an open window at the same time the householder finds his brew of beer turning sour.11

It was common for someone to make a casual observation of supposedly linked events (in the case above, the beer turning sour just as this poor woman happened to stroke her cat) and immediately assuming something sinister and linked by the events. Neighbors in areas that were prone to Witchcraft-accusations would commonly become involved in petty disputes (as neighbors in all times have) in which to blame something on Witchcraft was not an abnormal procedure. Such accusations, based in part on the post-hoc fallacy, become the basis of all superstition—most of which is harmless (such as the routines of many professional athletes)—but some of which occasionally deteriorates into the worst human folly and depravity. Most unjust persecutions and many wars were motivated by magical thinking, that is, by a failure to understand cause and effect at even a rudimentary level.

Additionally, there is a third apparent element; while not as significant as misogyny or magical thinking, it merits mention. It can be called the ‘German factor’. After decades of tedious work examining trial records and related documents, scholars now have a fairly good idea of some of the statistics associated with the Burning Times, from roughly 1300 to 1800. Current overall estimates run from approximately 35,000 to 65,000 ‘Witches’ killed, of whom around 22,000 were Germans—that is, about 44% of all those executed were German. No other nation comes close to this percentage; most have significantly smaller numbers, with France (around 5,500, or about 10%) coming next, followed closely by Poland and Switzerland. Many countries, such as England, lost less than a thousand. In the case of England this amounts to about one execution every four months, from 1450-1750, when most executions occurred—clearly lower than the average annual homicide rate for a large, modern European city.12 Other countries, like Italy and Spain, had relatively rare bouts of Witch-hysteria, and Eastern Europe was largely untouched by the Witch-craze. Modern scholarship, based on meticulous research, thus informs us of two things: the number of Witches killed during the Burning Times is much lower than was commonly assumed (as recently as in the 1970-80s); and Germans, followed distantly by the French, comprised the heavy majority. (Additionally, the term ‘Burning Times’ does not apply to England, where Witches were hung, not burned.13 The more primitive form of execution, burning, was exclusive to the Continent, and on occasion, Scotland).

Those who watched the popular documentary put out in 1990 by the reputable National Film Board of Canada (The Burning Times),

which featured a panel of modern neo-Pagans and Wiccans such as Merlin

Stone and Starhawk and other sympathizers like the renegade Christian

priest Matthew Fox, heard mention in the film of 'an upper figure of nine million Witches' being

killed during the Burning Times. That figure had been mentioned by

Gerald Gardner in his Witchcraft Today.14 He in turn appeared to get this figure from Margaret Murray’s The Witch-cult in Western Europe.

Back when Murray published her book (in 1921), scholarship on the

matter of Witches and the Burning Times was scant. It appears that

Murray got the ‘nine million’ figure from the 18th century

German scholar Gottfried Voigt (1740-1791), who—starting from just

forty-four confirmed executions in a small region of Germany—used a

peculiar method of mathematical extrapolation to arrive at ‘nine

million’ in a paper he published in 1784, a result now discredited as

wildly inaccurate by a multiplication factor of over a hundred. That

this figure has only been recently invalidated and the more accurate

estimate of between 40,000 and 60,000 executed now widely accepted by

scholars, is reflected in the number of neo-Pagans who still believe in a

‘women’s holocaust’ that wiped out women on a scale similar to the

Holocaust of World War Two (in which approximately six million men,

women, and children, mostly Jews, lost their lives).

Those who watched the popular documentary put out in 1990 by the reputable National Film Board of Canada (The Burning Times),

which featured a panel of modern neo-Pagans and Wiccans such as Merlin

Stone and Starhawk and other sympathizers like the renegade Christian

priest Matthew Fox, heard mention in the film of 'an upper figure of nine million Witches' being

killed during the Burning Times. That figure had been mentioned by

Gerald Gardner in his Witchcraft Today.14 He in turn appeared to get this figure from Margaret Murray’s The Witch-cult in Western Europe.

Back when Murray published her book (in 1921), scholarship on the

matter of Witches and the Burning Times was scant. It appears that

Murray got the ‘nine million’ figure from the 18th century

German scholar Gottfried Voigt (1740-1791), who—starting from just

forty-four confirmed executions in a small region of Germany—used a

peculiar method of mathematical extrapolation to arrive at ‘nine

million’ in a paper he published in 1784, a result now discredited as

wildly inaccurate by a multiplication factor of over a hundred. That

this figure has only been recently invalidated and the more accurate

estimate of between 40,000 and 60,000 executed now widely accepted by

scholars, is reflected in the number of neo-Pagans who still believe in a

‘women’s holocaust’ that wiped out women on a scale similar to the

Holocaust of World War Two (in which approximately six million men,

women, and children, mostly Jews, lost their lives).

Naturally, 40,000 to 60,000 executions—many of them accompanied by grotesque forms of torture and many dying in agonizing pain—does not somehow mitigate the horror and depravity of the various Inquisitions behind the executions. If there is any value in recognizing the difference between nine million and 60,000 or 40,000, it is solely in historical accuracy, not in some lesser depth of moral outrage, nor in any lesser need to understand how such things come to be in the first place.

Anyone seeking to examine the relationship between Church and Witchcraft ultimately ends up being faced with the realization that the deeper we look into the Church-Witchcraft dynamic, the more Witchcraft (real or not) vanishes. What is then revealed are three underlying relationships: the Church and Satan, and the Church (male clergy) and women, and a third—and perhaps most surprising—women and women.

The Church and Satan/The Church and Women

The first is essential to examine for the simple reason that the main argument behind the Church’s persecution of ‘Witches’ was that they were tools of the Devil—‘instruments of darkness’ as the historian James Sharpe put it. They were means to an end, simply pawns in the Devil’s plan to corrupt humanity. Accordingly, we need to take a look at the Church’s ideas around Satan, and in particular, the ways in which Satan was believed to manifest in physical reality.

In the most basic sense, the whole existence of Satan, especially as a shadowy, conspiratorial figure, has its roots, as alluded to above, in a deeply flawed grasp of cause and effect, namely the post-hoc fallacy. However, the delusions that gripped the Inquisitorial accusations against ‘Witches’ went further than this particular logical error. The ‘Devil’ became the sole causal factor behind all negative events—sickness, bad weather, ill fortune of all sorts. He was the ultimate scapegoat—‘Witches’ were used as vehicles to punish as they provided a tangible face for the Devil.

Part

of the problem lay in the fact that the nature of Satan himself was a

matter of endless dispute amongst theologians and Church authorities

going back to the 1st century AD. There were many competing

theories and assumptions, and this can be seen in the various different

guises of Satan in the Bible itself. In the Old Testament, Satan appears

to act purposefully, or as in the case of the Book of Job, as a

‘tester’ of humanity and an accomplice of God. But in the New Testament,

he seems to be out of control, or as historian Gerard Messadie put it,

‘behaving like the demons of Oceania and Australia, doing everything

willy-nilly. Everyone had come to believe himself threatened by a Devil

who was as uncontrollable as a rabid dog.’15 It was in the

New Testament that the Devil came to associated with such things as

leprosy, blindness, paralysis, epilepsy—in short, with illness

itself—and, to boot, with ugliness and physical deformities as well. The

Devil became the chief personification of evil fortune, and

accordingly, a highly useful tool to wield against enemies—be they

theological, political, or psychological in nature. And more

specifically, this sort of Devil was needed as a pure contrast to aid in

highlighting the divine purity of Jesus. The ‘whiter’ Jesus is, the

more a purely ‘blackened’ oppositional factor is required. (And indeed,

the Devil in ‘Witches sabbats’ was usually depicted as being cloaked in

black). As the idea of divine incarnation is introduced—pure goodness—so

does its opposite naturally leap into existence, in accordance with the

inescapable laws of duality.

Part

of the problem lay in the fact that the nature of Satan himself was a

matter of endless dispute amongst theologians and Church authorities

going back to the 1st century AD. There were many competing

theories and assumptions, and this can be seen in the various different

guises of Satan in the Bible itself. In the Old Testament, Satan appears

to act purposefully, or as in the case of the Book of Job, as a

‘tester’ of humanity and an accomplice of God. But in the New Testament,

he seems to be out of control, or as historian Gerard Messadie put it,

‘behaving like the demons of Oceania and Australia, doing everything

willy-nilly. Everyone had come to believe himself threatened by a Devil

who was as uncontrollable as a rabid dog.’15 It was in the

New Testament that the Devil came to associated with such things as

leprosy, blindness, paralysis, epilepsy—in short, with illness

itself—and, to boot, with ugliness and physical deformities as well. The

Devil became the chief personification of evil fortune, and

accordingly, a highly useful tool to wield against enemies—be they

theological, political, or psychological in nature. And more

specifically, this sort of Devil was needed as a pure contrast to aid in

highlighting the divine purity of Jesus. The ‘whiter’ Jesus is, the

more a purely ‘blackened’ oppositional factor is required. (And indeed,

the Devil in ‘Witches sabbats’ was usually depicted as being cloaked in

black). As the idea of divine incarnation is introduced—pure goodness—so

does its opposite naturally leap into existence, in accordance with the

inescapable laws of duality.

Yahweh of the Old Testament carries within him darker strains than Jesus does. Not that Jesus is without occasional aggression (ejecting the money-changers from the temples, cursing a fig tree, condemning the Pharisees, etc.), but he embodies the teaching of forgiveness—‘love your enemies’—in a way that Yahweh certainly does not. In some ways Yahweh is a god of war. Because he is no example of stainless ‘goodness’, he does not require any counter-force of pure capricious evil, and this is why the Satan of the Old Testament does not have the nasty sting of Satan of the New Testament. As Jesus was introduced, so is evil enhanced and given a darker and more gratuitous shade of malice.

In the first few centuries after Christ there was much theological hair-splitting around the nature of Satan and his army of demons, and the belief that there was more than one kind of evil spirit. At the council of Constantinople in 543, a canon was introduced that proclaimed there was, essentially, only one kind of demon. This narrowed the focus and made it easier to ascribe all evil events to this singular force of evil. Even science, and especially mathematics, was until the late 17th century suspected by many of being the work of the Devil, which was why Copernicus did not publish his work demonstrating that the Earth is not the center of the universe until on his deathbed, and why Galileo, as late at 1615, was forced to recant his confirmation of Copernicus’s idea.

As

the Dark Ages passed into the Middle Ages, the Devil took on an actual

mythic form—generally that of a distorted version of the Greek god Pan,

or the Roman god Faunus—complete with hooves, horns, general goat-like

attributes, and a dark, wild, sexual look. The sexual element in his

makeup was of major significance, not just because of the celibacy of

many Catholic clergy, but also because of the purity and saintliness

ascribed to Jesus. This purity always seemed to exclude his sexuality in

such a way as to almost render him asexual. (Not to mention, he was

held to have been brought into the world via a virgin birth).

Accordingly, the Devil would naturally embody the polar opposite of all

that, and this was exemplified in the belief in the existence of the

notorious demonic ‘Incubi’, subordinates of the Devil, spirits that were

alleged to visit women at night and make love to them in such a way as

to incite wild orgasms. (The equivalent female demons, said to visit men

at night, were called the ‘Succubi’).

As

the Dark Ages passed into the Middle Ages, the Devil took on an actual

mythic form—generally that of a distorted version of the Greek god Pan,

or the Roman god Faunus—complete with hooves, horns, general goat-like

attributes, and a dark, wild, sexual look. The sexual element in his

makeup was of major significance, not just because of the celibacy of

many Catholic clergy, but also because of the purity and saintliness

ascribed to Jesus. This purity always seemed to exclude his sexuality in

such a way as to almost render him asexual. (Not to mention, he was

held to have been brought into the world via a virgin birth).

Accordingly, the Devil would naturally embody the polar opposite of all

that, and this was exemplified in the belief in the existence of the

notorious demonic ‘Incubi’, subordinates of the Devil, spirits that were

alleged to visit women at night and make love to them in such a way as

to incite wild orgasms. (The equivalent female demons, said to visit men

at night, were called the ‘Succubi’).

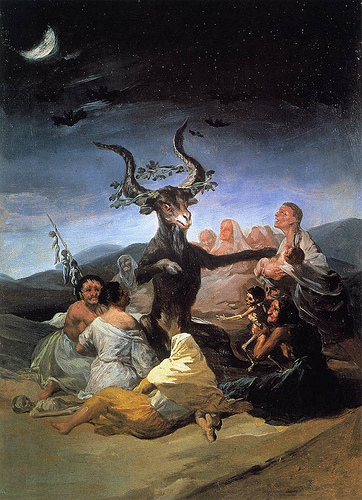

In fact, when the historical records concerning the alleged gathering of ‘Witches’—typically called ‘sabbats’—is examined, it becomes clear that the entire thing was largely a simple inversion of Christian values—in effect, a type of religious psychopathology. Sabbats were reported to have generally involved ‘Witches’ gathering late at night in a wild place, in a meeting that was led by the Devil himself, generally in a black goat-like or dog-like form, dressed in black and seated on a black throne—perhaps best depicted by the famous Spanish painter Francisco Goya in his 1823 work El Aquelarre (‘the Witch’s Sabbat’). These meetings involved a great deal of sexuality, such as the ‘Witches’ being required to kiss the Devil’s genitals and anus, and the whole gathering concluding with the Devil copulating with everyone present.16 The blackness of the Devil, and rampant sexual energy, can all easily be seen as more of a direct peak into the contents of the repressed unconscious mind (of religious ‘authorities’, or of the common folk), than to any real ceremonies involving actual people. In that sense, Church and Witchcraft or Church and Women, becomes, more accurately, Church and Satan—or even more to the point, male clergy and the common folk and their own repressed sexuality. However, as we will see shortly, that dynamic was not the only one of import going on.

Women and Women

An important element to understand in the Church’s claimed rationale for the Witch-hunts was the idea of maleficia. This word (from the Latin malitia, ‘ill will’) was the Church’s term for the ‘evil spells’ and assumed ‘malefic influence’ of ‘Witches’. The whole argument around the need to hunt them down and be rid of them was based on the belief that not only did they exist, but that they were actively involved in causing evil fortune to those around them (which included such things are crops, animals, and so on).

One thing need always be born in mind when attempting to understand some of the motives behind the Witch-craze of the Burning Times, as well as far earlier examples of the persecution of those thought to possess occult powers (or ‘psychic’ powers, as the more common modern term has it), and it is this: despite the obvious irrationalism of the Witch-persecutions, it has been a long standing belief, found in almost all old cultures on Earth, that people possessing such powers—‘sorcerers’, for want of a better term—have always existed. Here in our modern era of ‘scientific enlightenment’ and sophisticated technology we may have a hard time realizing to what extent this was (and still is, in many places) true. The advent of weapons, especially handguns, altered much of this—after all, what need is there to place hexes on enemies when you can simply shoot them? (Although it is interesting to note that the early muskets first used in Europe in the 15th century were thought by some to be tools of the dark arts, owing not just to their deadly power, but also to the sulfurous smell following their discharge).17 James Frazer, in his The Golden Bough, describes many examples of how cultures prior to the Renaissance made regular practice of guarding against malefic sorcery.18 This is common in the East was well. Even Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, which traditionally (certainly prior to the mid-20th century annexation of Tibet by China) taught some of the most philosophically advanced material concerning the path of spiritual transformation, commonly have ‘protector deities’ called Dharmapalas, whose spiritual agency is involved in safeguarding the Dharma and the monks who practice it, from evil forces. The scholar Mircea Eliade also discusses the commonality of this practice within global shamanic tradition.19 Norman Cohn, in his exhaustive study of the European Witch-craze, provides many examples from direct historical records.20

The power of the mind in bringing about tangible effects from such beliefs—and especially for such beliefs to catch on, on a mass level—can never be underestimated. The anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss once wrote,

We understand more clearly the psycho-physiological mechanisms underlying the instances reported from many parts of the world by exorcism and the casting of spells. An individual who is aware that he is the object of sorcery is thoroughly convinced that he is doomed according to the most solemn traditions of his group. His friends and relatives share this certainty. From then on the community withdraws. Standing aloof from the accursed, it treats him not only as if he were already dead but as though he were a source of danger to the entire group.21

I include these mentions of the commonality of belief in ‘malefic occult power’ in this subsection on ‘Women and Women’, because what is not generally recognized is the extent to which women have been involved, historically, in not just being accused of using ‘evil occult powers’, but in accusing other women of evil occult powers.

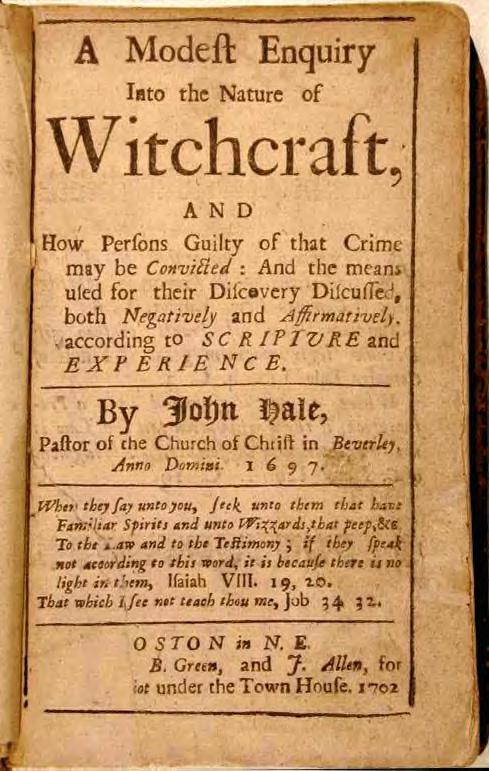

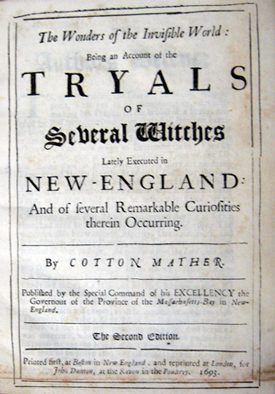

A relatively recent, and uniquely Western, version of this unfolded with the infamous Salem Witch trials that took place on the east coast of the United States from 1692-93. Space does not permit for an in depth look at this event,22 but in brief, over a fourteen month span, twenty-nine people were convicted of Witchcraft in three counties of Massachusetts (Essex, Suffolk, and Middlesex), though mostly centered on the town of Salem, in Essex. Of those, nineteen were eventually executed (all by hanging)—fourteen women, five men. The entire matter began with two young girls (aged nine and eleven) undergoing spontaneous bouts of hysteria (that resembled epilepsy, but that appeared to have been psychosomatic or deliberately enacted). This behavior soon ‘spread’ to several other young women in the communities. A doctor then diagnosed ‘Witchcraft’ as the likely cause behind the strange behavior of the two young girls—that is, they had been ‘hexed’ by someone. The youngest of these girls, under pressure to point a finger, did so—first at a local black Caribbean slave girl who used to entertain them with stories—and then both young girls accused two other young women as well. All three of these women were then arrested (with the accusations of the young girls being backed up by others at this point). Under interrogation, the three ‘admitted’ to Witchcraft.

Just

a few days after this, four more women began showing signs (so they

believed) of being afflicted by Witchcraft. Over the next month,

numerous other young women were accused, most by other women, of

Witchcraft—including a four year old girl. What is more

extraordinary, this small child, after being accused of being a Witch,

was actually arrested, interrogated, and kept in prison for nine months.

Although not ultimately executed, she went temporarily insane. In the

end, dozens were accused, and a number of these were eventually hung.

What was significant was that ‘spectral evidence’ was often used, this

being ‘evidence’ gained via visions or dreams, almost all of which was

coming from the women. Although men were involved in the Salem trials,

and some men were even convicted and hung, the majority of the whole

affair was precipitated by women (many young or teenage girls, although

some older women were involved too) accusing other women.

Just

a few days after this, four more women began showing signs (so they

believed) of being afflicted by Witchcraft. Over the next month,

numerous other young women were accused, most by other women, of

Witchcraft—including a four year old girl. What is more

extraordinary, this small child, after being accused of being a Witch,

was actually arrested, interrogated, and kept in prison for nine months.

Although not ultimately executed, she went temporarily insane. In the

end, dozens were accused, and a number of these were eventually hung.

What was significant was that ‘spectral evidence’ was often used, this

being ‘evidence’ gained via visions or dreams, almost all of which was

coming from the women. Although men were involved in the Salem trials,

and some men were even convicted and hung, the majority of the whole

affair was precipitated by women (many young or teenage girls, although

some older women were involved too) accusing other women.

Cases involving the factor of ‘women against women’ or exclusive female hysteria were not unique to Salem of 1692-93. Earlier cases abound, a spectacular example being sixteen Catholic nuns of Loudon, in western France, who in 1634 underwent spontaneous mass hysteria in such a fashion that all observing became convinced that they’d been possessed by demons. A local priest (Urbain Grandier) was eventually convicted of witchery, and accordingly tortured and burned alive. (His actual crime had been that he’d had sexual relations with some of the nuns). Both the Salem and Loudon events received 20th century literary and Hollywood treatments; Salem via Arthur Miller’s 1953 play, and the 1996 film (both called The Crucible); and Loudon via Aldous Huxley’s 1952 historical novel The Devils of Loudon, and Ken Russell’s 1971 film adaptation of Huxley’s novel, called The Devils.

Salem and Loudon were only the high profile cases, however. Perhaps more specifically, detailed historical records from small towns throughout Western Europe, mostly concerning the period of the 15th to 17th centuries, shows many examples of villagers caught up in petulant quarrels, accusations, and counter-accusations—in large part leveled by women against women—involving disputes over land, matrimonies, rents in arrear, and all the usual issues of conflict found in any small town. Many of these accusations inevitably involved maleficia—and with that, the accusation of ‘Witchcraft’. Many, if not most, ended in convictions and burnings.23 (An excellent representative case study, brought out in 2009 by the American historian Thomas Robisheaux, called The Last Witch of Langenburg, covers in exhaustive detail a drama that unfolded in the German town of Langenburg in 1672, in which the relations between villagers, and in specific, between women and women, was the actual driving force behind one of the last ‘Witch-panics’ of Europe).24

None of this is to propose that the Inquisitions behind the Witch-craze itself was not a male-perpetuated phenomena. It ultimately was. But when one studies the detailed histories compiled by such rigorous scholars as Diane Purkiss, Norman Cohn, Robin Briggs, or Thomas Robisheaux, one is left with the realization that women accused other women of Witchcraft far more commonly than is popularly realized today.

Whence Witchcraft?

From all this arises a natural question, and one that has troubled historians for many years: Was there, in fact, any actual pre-20th century pagan tradition called ‘Witchcraft’? In answer to this, two extremes have arisen: the first, probably best exemplified by the fanatic priest Montague Summers (1880-1948), is that not only is Witchcraft both real and ancient, it is a tool of Satan and has only one purpose, that being to lead people astray from Christ and God. At the other end of the pole, we have scholars like Norman Cohn and Rossell Robbins, who after exhaustive research and admittedly persuasive argument, conclude that historical Witchcraft is purely fantasy, based mostly on forged documents, pathological delusions, and livelihoods (sanctioned Witch-hunters were, after all, paid for their services). Somewhere in the ‘middle’, we have many modern Wiccan and Neo-Pagans—perhaps best summarized by Margot Adler who wrote that ‘the truth probably lies somewhere in between’ the two poles just mentioned—most of whom subscribe to a version of Margaret Murray’s ideas (see below).

As mentioned above, much of contemporary Witchcraft, Wicca, or Neo-Pagan traditions and networks can, without difficulty, trace their roots at least back to the 1950s and Gerald Gardner (1884-1964). Gardner claimed actual direct influence from underground groups—in specific a coven in southern England, that he called the ‘New Forest coven’—that he said he had been initiated into in 1939. It was from this coven that Gardner claimed to derive authority to launch a modern day ‘revival’ of the Witchcraft faith. He further maintained that this coven was carrying on the tradition of an ancient Witch-cult that derived from pre-Christian times, a type of original European shamanism, only one that had a fair degree of organization.

For years serious researchers tended to dismiss Gardner’s ‘New Forest coven’—its existence never corroborated by anyone—as simply a device to legitimize his creation of a 20th century Pagan tradition. Many writers have used this device in the past—that is, to fabricate a legendary teacher or secret society of teachers, through which to propagate a group of ideas. Examples of this in more recent times, of varying degrees of legitimacy, have included H.P. Blavatsky (‘the Mahatmas’), William Wynn Wescott (‘Fraulein Anna Sprengel, Secret Chief’ for the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn), G.I. Gurdjieff (the ‘Sarmoung Brotherhood’), T. Lobsang Rampa (‘Tibetan masters’), Carlos Castaneda (‘men of knowledge’ don Juan Matus, don Genaro, and others), Kyriacos Markides (‘Daskalos’ and his circle of Cypriot Greek mystics), and Gary Renard (‘ascended’ masters).25 The method, a type of deux ex machina, is clearly time-honored, and often works for how it is intended. It works in the same way that theatre, fictional literature, and the modern art form of cinema does, being based on the human ability to suspend disbelief and ascribe reality to something imaginary—a reality that easily goes beyond mere entertainment and can even become regarded as gospel truth that people will willingly kill or be killed for.

Gardner had been an English colonial bureaucrat and amateur anthropologist who spent many years in south-east Asia. In the late 1930s he made contact with a Rosicrucian order in southern England. It was from within this order that Gardner claimed he connected with a small group of people who in 1939 took him through an initiation that he identified as being of the tradition of Witchcraft, and in particular of the type that had managed to survive underground for many centuries. Gardner further claimed that the leader of this group was a woman name Dorothy Clutterbuck, that she was the ‘High Priestess’ of an actual coven of Witches in the New Forest area. Subsequent research has shown that Gardner was the sole source of the claim about Clutterbuck. Not only are there no corroborating sources, Clutterbuck’s own diaries from that time make no mention of any sort of occult, let alone Witchcraft-related, activities. Further, there was a problem with Gardner’s integrity concerning the matter of forgery. In 1946 he had claimed, to the members of the Folklore Society, to have doctorates from the universities of Singapore and Toulouse, claims later proven to be false.26

In

May of 1947, Gardner, aged 62, met the controversial magus Aleister

Crowley, himself 71 at the time and in the last year of his life.

Gardner and Crowley became friends of sorts, and after several informal

meetings, Crowley authorized Gardner to set up a branch of the Ordo

Templi Orientis (OTO) in England (the fraternity that Crowley was head

of, although it had become temporarily defunct in England at that time).27

Crowley provided Gardner with papers containing information of specific

rituals and teachings. Crowley gave Gardner the name ‘Brother Scire’

(which Gardner would later use as his ‘Craft name’) and initiated

Gardner into the 7th degree of the OTO. Nothing however would come of this and Gardner never did begin an OTO lodge in England.

In

May of 1947, Gardner, aged 62, met the controversial magus Aleister

Crowley, himself 71 at the time and in the last year of his life.

Gardner and Crowley became friends of sorts, and after several informal

meetings, Crowley authorized Gardner to set up a branch of the Ordo

Templi Orientis (OTO) in England (the fraternity that Crowley was head

of, although it had become temporarily defunct in England at that time).27

Crowley provided Gardner with papers containing information of specific

rituals and teachings. Crowley gave Gardner the name ‘Brother Scire’

(which Gardner would later use as his ‘Craft name’) and initiated

Gardner into the 7th degree of the OTO. Nothing however would come of this and Gardner never did begin an OTO lodge in England.

According to Wiccan lore, as first told by Raymond Buckland (one of the earliest initiates of Gardner’s Wicca), in the 1940s Gardner began pressing ‘Old Dorothy’ Clutterbuck and her fellow Witches for permission to write a book about their existence and activities. The Witches allegedly declined, presumably because Witchcraft at that time was still illegal in England (and remained so until 1951). Eventually the New Forest Witches allowed Gardner to write about them, but only in veiled terms. This he did by writing the novel High Magic’s Aid, which he published in 1949, under his OTO initiate name ‘Brother Scire’. After the repeal of the last Witchcraft laws two years later, Gardner claimed he again approached the coven and this time was granted, somewhat reluctantly, permission to write about them in a non-fictional form, which Gardner did with his 1954 book Witchcraft Today. Gardner felt it was important to write about the ‘authentic Craft’ before it disappeared altogether.28 This, incidentally, was the same sentiment that gripped Israel Regardie when he broke his vows and published the ‘knowledge lectures’ and full rituals of the Golden Dawn in 1939.

According

to the scholar Richard Kaczynski (and others, such as Leo Ruickbie and

Ronald Hutton), Aleister Crowley’s influence on Gardner and future

Gardnerian Wicca had been considerable. Kaczynski remarks,

According

to the scholar Richard Kaczynski (and others, such as Leo Ruickbie and

Ronald Hutton), Aleister Crowley’s influence on Gardner and future

Gardnerian Wicca had been considerable. Kaczynski remarks,

Gardnerian Witchcraft, particularly in its earliest forms, is clearly derivative of Crowley. The symbolic great rite comes from the OTO’s VIo ritual; the pagan catchphrase ‘Perfect love and perfect trust’ is drawn from ‘The Revival of Magick’ [a Crowley essay], and the Wiccan IIIo initiation—the highest in the Craft—is essentially a Gnostic Mass [a mystical rite written by Crowley in Moscow in 1913, based in part on the Eastern Orthodox Mass]. The pagan banishing [ritual] originates with the Golden Dawn [the organization that first trained Crowley], and the summoning of the Four Watchtowers [a Wiccan rite] is right out of John Dee’s Enochian magic [a 16th century system taught in the Golden Dawn in the 1890s and practiced by Crowley in Africa in 1909]. And, for all of its evocative beauty, the Charge of the Goddess is largely a paraphrase of The Book of the Law [Crowley’s main text, written in 1904]. Margot Adler reflects the prevalence of this opinion when she quotes a Wiccan priestess who wrote to her, ‘Fifty percent of modern Wicca is an invention bought and paid for by Gerald Gardner from Aleister Crowley. Ten percent was ‘borrowed’ from books and manuscripts like Leland’s text Aradia. The forty remaining percent was borrowed from Far Eastern religions and philosophies.’ 29

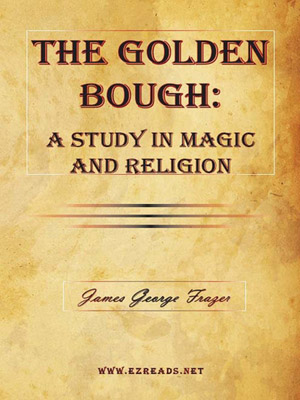

Gardner (as influenced by Crowley, the Golden Dawn, and others) may have been the practical force behind the creation of 20th century Wicca, and for this alone, many modern Wiccans hold him in considerable esteem. If nothing else he was resourceful and wise in a pragmatic fashion, in a way that allowed thousands to gain (or recover) a passion for some form of organized religion. However Gardner was not the main intellectual source of modern Wicca. That honor appears to go to Margaret Murray (1863-1963), and standing behind her, the figure of James Frazer (1854-1941) and in particular, his toweringly influential work The Golden Bough (first published in part in 1890, with additions from 1906-15, and then in full in 1922).

Murray

was primarily an Egyptologist who spent eleven years as an assistant

professor of Egyptology at the University College of London (1924-35).

Her main accomplishment was developing her theory of a surviving Western

European ‘Witch-cult’, one that for centuries had been persecuted by

the Church, but that had managed to persist into the present day in a

very low profile form. Over the decades since the publication of her

work in 1921, she has been taken to task by numerous historians and

scholars who cite her questionable scholarship, one practice of which

involved Murray selectively deleting sections of records she was quoting

in order to bolster her argument. The historian Norman Cohn, after a

long study of her primary sources that she used for her thesis,

concluded,

Murray

was primarily an Egyptologist who spent eleven years as an assistant

professor of Egyptology at the University College of London (1924-35).

Her main accomplishment was developing her theory of a surviving Western

European ‘Witch-cult’, one that for centuries had been persecuted by

the Church, but that had managed to persist into the present day in a

very low profile form. Over the decades since the publication of her

work in 1921, she has been taken to task by numerous historians and

scholars who cite her questionable scholarship, one practice of which

involved Murray selectively deleting sections of records she was quoting

in order to bolster her argument. The historian Norman Cohn, after a

long study of her primary sources that she used for her thesis,

concluded,

Margaret Murray’s knowledge of European history, even of English history, was superficial and her grasp of historical method was non-existent. In the special field of witchcraft studies, she seems never to have read any of the modern histories of the persecution…by the time she turned her attention to these matters she was nearly sixty, and her ideas were firmly set in an exaggerated and distorted version of the Frazerian mold.30

By ‘Frazerian mold’ Cohn was referring, of course, to James Frazer. Frazer’s work The Golden Bough

argued for the existence of a near universal ‘fertility cult’ involving

the deification of a sacred king—and on occasion, the sacrifice of such

a king.31 A main part of Frazer’s thesis was that age-old

fertility rites are ultimately about the need to kill off the old spirit

of Nature and then bring it back life—to resurrect it—in a form that

was commonly that of worshipping and then killing (sacrificing) a sacred

king.

He argued that world mythologies tend to consistently reflect

this legend, which generally involves a solar deity or king marrying an

Earth goddess. The king then dies at harvest time, only to be reborn in

the spring time. (Note the connection there with Easter and the

‘resurrection’ of Jesus). The old religions were, thus, deeply

intertwined with agriculture and the timing of the seasons.

He argued that world mythologies tend to consistently reflect

this legend, which generally involves a solar deity or king marrying an

Earth goddess. The king then dies at harvest time, only to be reborn in

the spring time. (Note the connection there with Easter and the

‘resurrection’ of Jesus). The old religions were, thus, deeply

intertwined with agriculture and the timing of the seasons.

It was from this thesis that Margaret Murray developed her idea of an ancient, organized pagan faith that had survived the Witch-craze, and whose rites and ceremonies had been simply misinterpreted by Church authorities and the common folk. The problem with her idea is that historical research has unearthed no evidence of organized paganism, in particular in the form of meetings called ‘sabbats’. Moreover, all of the records used by Murray as evidence to support her thesis, contained fantastic imagery (Witches flying to sabbats, the Devil copulating with the Witches, babies being eaten, and so forth), the worst and most fantastic passages of which she was found to have selectively left out when quoting the records of them.32

And so the irony: Margaret Murray wrote a short Introduction to Gardner’s landmark Witchcraft Today, endorsing the author’s writings about an ancient and legitimate organized Witchcraft, when she herself (with unwitting help from James Frazer) is likely the true ‘High Priestess’ and unintentional founder of modern Wicca. Indeed, there is a strong probability that the New Forest coven that Gardner claimed to have been initiated in, did in fact exist in some form, but that it had come into being only in the 1920s, basing its ideas on Murray’s work. (The 1920s was an extraordinarily fertile decade for metaphysical teachings of all stripes, a sort of pre-WWII precursor of the ‘new age’ movement that blossomed in the 1970s and 80s).

Two

other sources bear mentioning: the American journalist and folklorist

Charles Leland (1824-1903), who made an extensive study of Gypsies and

in 1899 published Aradia or the Gospel of the Witches, a

book known to have influenced some of the Wiccan rites created by

Gardner half a century later. The other important literary figure was

Robert Graves, especially via his influential The White Goddess (1948),

a poetic work that outlined the idea of an overarching Goddess

tradition found throughout history, in which feminine deities are

connected to the Moon. Graves claimed to take Frazer’s ideas outlined in

The Golden Bough, and render them more detailed and explicit. The White Goddess

has been panned by numerous critics for its questionable historical

research—and Graves himself admitted it was primarily a poetic

venture—but the book remained nonetheless a strong influence on many 20th century Pagans.

Two

other sources bear mentioning: the American journalist and folklorist

Charles Leland (1824-1903), who made an extensive study of Gypsies and

in 1899 published Aradia or the Gospel of the Witches, a

book known to have influenced some of the Wiccan rites created by

Gardner half a century later. The other important literary figure was

Robert Graves, especially via his influential The White Goddess (1948),

a poetic work that outlined the idea of an overarching Goddess

tradition found throughout history, in which feminine deities are

connected to the Moon. Graves claimed to take Frazer’s ideas outlined in

The Golden Bough, and render them more detailed and explicit. The White Goddess

has been panned by numerous critics for its questionable historical

research—and Graves himself admitted it was primarily a poetic

venture—but the book remained nonetheless a strong influence on many 20th century Pagans.

All valid historical criticism aside, there is bound to be some semblance of truth in the ideas best represented by Margaret Murray’s work, because loosely organized spiritual traditions have existed for millennia, most of which can be categorized by the term ‘shamanistic’. Medieval or Renaissance era sabbats and orgies involving ‘the Devil’ and thirteen ‘Witches’ is indeed likely the product of fantasy or religious agenda—and organized Witchcraft, along the lines of modern Wicca, in any form prior to the 1920s is indeed probably only wishful thinking—but the existence of shamanic spiritual teachings throughout history is indisputable, and this would naturally include European cultures as well.

However, the distinction between legitimate shamanistic practices, and the idea of an organized spiritual tradition such as modern Wicca stretching back into antiquity, needs to be carefully understood. It is all too tempting to dismiss out of hand the stark historical work of scholars like Norman Cohn who find absolutely no evidence for anything like a pre-20th century European Witchcraft, merely on the basis of what appears to be an egg headed approach lacking in experiential understanding. For example, in commenting on Cohn’s work Europe’s Inner Demons, the 20th century author and Pagan Margot Adler remarks,

One of the problems with Cohn’s argument is his limited conception of what is possible in reality. For example, he considers all reports of orgies to be fantasy…he is surprisingly ignorant of the history of sex and ritual. Orgiastic practices were a part in religious rites in many parts of the ancient world.33

That may be so, but it still does not prove the existence of organized Witchcraft prior to the 20th century. Adler’s only other significant criticism of Cohn, that he uses psychoanalysis in interpreting the possible roots of what he believes to be the fantasies at the heart of Renaissance ‘Witch sabbats’—a psychoanalysis that she calls ‘the most popular witchcraft religion of our day’—does not negate the meticulous historical research that he, and other scholars, undertook. The core issue remains: no historical evidence for an ancient organized faith like modern Witchcraft has yet been found. The modern version of Witchcraft (Wicca) bears almost entirely late 19th and early 20th century influences: Margaret Murray, James Frazer, Charles Leland, Aleister Crowley, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, Robert Graves, and Gerald Gardner. To that, we can safely add Rosicrucianism and Freemasonry—the former an influence on both Gardner’s ‘New Forest coven’ as well as on the Golden Dawn, and the latter an influence on both the Golden Dawn and Crowley.

Interpretation

The relationship between the Church and Witchcraft was an extremely complicated phenomenon, involving religious, political, social, psychological, and economic elements. And these were only the large-scale factors. Added to that was the mix of human petulance and general capacity for mean-spiritedness of all sorts, as well as a depraved ‘appetite’ (there is no better word) for sadism, torture, and humiliation to unfathomable degrees.

What is striking to note is that of all the more recent primary influences on modern Wicca (mentioned above) all, with the exception of Murray, are male. The irony of this, and in particular of the patriarchal Freemasonry ancestral link with modern Wicca (via the Golden Dawn and Crowley), is marked, but perhaps understandable. When the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn was founded in England in 1888, it was done so by three Freemasons (William Woodman, William Wynn Westcott, and Samuel Mathers), partly in order to investigate esoteric teachings more deeply, but also partly to break the traditional Masonic gender barrier and grant women admission. The Golden Dawn, at its height in the late 1890s, did comprise around 35% female membership; some of the more prominent women involved were stage actress Florence Farr, theatre producer Annie Horniman, future Rider-Waite Tarot deck artist Pamela Coleman-Smith, scholar and author Evelyn Underhill, actress Sarah Allgood, and author, feminist, and Irish revolutionary Maud Gonne. All these women practiced the Golden Dawn version of ceremonial magic, with its roots in much older ritual magic—and just as certainly all these women would have been accused of consorting and fornicating with the Devil only a century or two earlier. (Not that late 19th century England was of equal tolerance compared to the early 21st century Western world—as mentioned, Witchcraft remained illegal in England until 1951—but the ‘craze’ element involving Witchcraft accusations, resulting hysteria, and vicious persecutions, had long since gone, at least from Europe and North America).

In looking at psychological interpretations, arguments can be mounted in support of the idea that the Witchcraft persecutions were largely a matter of the repressed sexual energy of male religious authorities finding outlet in the depraved and licentious imagery of the Devil. And it is indeed reasonable to wonder, for example, at the sex lives of the two ‘authorities’ (Kramer and Spengler) who authored the lurid and influential Malleus Maleficarum. Arguments can also be mounted that the old occult idea that the female mind carries within it the seeds of chaos and the tendency toward interpersonal strife, and a far greater propensity toward the carnal, is valid; and that accordingly, women had a much greater hand in the Witch-craze than assumed. All these gender issues, however, would seem to be a matter impossible to unravel in this case because of the lack of consistent records. But more to the point, gender issue here is ultimately a secondary concern (unpopular as that idea may seem to some). What is more useful to look at is the entire nature of the conflict inherent in religion, in specific its often confused relationship with the carnal.

The

very image of the Devil in the standard descriptions and depictions of

him, as he consorts with his ‘Witches’ in sabbats that invariably

involve kinky sexuality, bears looking closely at—for example, the

tradition of Witches kissing the Devil’s anus. Why the anus? It is, in a

sense, the part of the body that is the real ‘forbidden fruit’, more so

than the genitals. The genitals may be feared, unconsciously, as the

center of sexual power, but the anus is associated with elimination,

waste, and dead matter (and thus, with death itself). It is the orifice

of the body concerned with expelling the old and useless, and it is also

the source of the worst smells. It is, in a sense, the ‘hidden portal’

and ‘final taboo’.

The

very image of the Devil in the standard descriptions and depictions of

him, as he consorts with his ‘Witches’ in sabbats that invariably

involve kinky sexuality, bears looking closely at—for example, the

tradition of Witches kissing the Devil’s anus. Why the anus? It is, in a

sense, the part of the body that is the real ‘forbidden fruit’, more so

than the genitals. The genitals may be feared, unconsciously, as the

center of sexual power, but the anus is associated with elimination,

waste, and dead matter (and thus, with death itself). It is the orifice

of the body concerned with expelling the old and useless, and it is also

the source of the worst smells. It is, in a sense, the ‘hidden portal’

and ‘final taboo’.

The slang expression ‘kiss my ass’ is generally recognized as an insult, but what kind of insult in specific? From the egocentric perspective, it is one that involves, above all, humiliation—the rendering of the ‘other’ into an object. (Pornography, in its lowest light, operates in a similar mode). However, the one humiliating is not necessarily ‘alone’ in actualizing their secret sadistic lusts—the one being humiliated may also be, to some degree, participating in a deeply repressed masochistic fantasy. And it is precisely this degree of repression that makes a ‘forbidden zone’ so potentially eroticized.

Caution, of course, is needed here—the violence against, and debasement of, women throughout the centuries cannot be blamed on some actualization of their dark masochistic fantasies. However in order to glean some manner of insight from the Witch-craze and in particular, to be able to apply this insight into our present lives, we need to look squarely into our more repressed desires—whether we be male or female. As Isaac Bashevis Singer once wrote, ‘We are all black magicians in our dreams, in our fantasies, perversions, and phobias…’34

Looking into repressed desires, however, means inner work, in the most real sense of that term. Such work is rarely easy, in part because most of us know that to honestly and deeply face our secret and hidden fantasies is to uncover potentially powerful energies. Such power always carries within it the potential for bringing about significant changes in our life—the proverbial ‘rocking the boat’. Most of us are creatures of habit, and most of us tend to equate significant changes with stress. Accordingly, most people fear looking within in a deeply honest fashion, and as a result never penetrate to any depth of self-honesty. The result is to live a life based more on superficial views, status quos, and accepting what is ‘traditionally’ held to be true. In the case of the Witch-craze, it is not hard to see how this type of psychological intransigence was a key element in keeping the whole (essentially crazy) matter going for centuries.

We live in an era where rationalism—at least as an ideal—rules, even if such rationalism amounts to little more than a need to demonstrate that one is not making false claims (as in the academic concern with citations). Much of the Witch-craze was based on false claims, with the worst example being the ‘spectral evidence’ (as for example, in the Salem case, where one could claim that one had seen a ghost or non-physical demon accost someone, and on that basis, accuse someone of Witchcraft). However what we tend to overlook, in this time of scientific materialism and high tech gadgetry, is that there is a great degree of vibrancy in living an embodied life, one in which all human subjective domains (for example, thinking, feeling, intuition, sensing) are in relative balance. In such a world, the unconscious mind may be said to interface more easily with the conscious mind, and thus myths, legends, superstitions, and even dreams potentially carry more reality. The gift of the so-called ‘Age of Reason’ (beginning in earnest roughly around 1700, initiated just prior to that by Copernicus, Galileo, Descartes, Newton, and others), has been to aid in dispensing with the more dangerous and troubling elements of an ‘enchanted’ life (and the ending of the Witch-craze, essentially by the late 1700s, testifies in part to that). But there has also been a cost, and that is that most people are now less ‘embodied’—that is, live more through their minds (and technology—just step into a modern Western café in current times, and see most young people lost in their laptops or smart phones).

My point here is not to suggest that life during the Witch-craze was somehow preferable to modern life; it certainly wasn’t, except perhaps for all but the most incurable romantic. Most will happily take modern technological obsession, depression, boredom, and global terrorism over plague, rampant disease, malnutrition, religious and racial intolerance, grinding poverty, high infant and child mortality rates, and an average lifespan of 40 or 50 years, any day. However it was not entirely worse back then—the lack of sophisticated technology, the stronger relationship with the raw environment, the greater degree of worldly innocence, the greater need to actually interact with people and make powerful efforts to accomplish even simple things, doubtless meant a world where people were, in the main, more ‘embodied’ than now in our softer, more virtual society. I stress this point because it is all too easy to dismiss the Burning Times as an example of a primitive society in which absurd and dangerous superstitions were granted free reign, with terrible consequences. The casual assumption is that we are now beyond such things. In reality, however, our various psycho-pathologies have just assumed more varied and subtle forms.

While the story lines of the dramas of spiritual conflict played out throughout history—be that between Osiris and Set, or Jesus and Judas, or the Church and Witchcraft—may be constantly changing, the underlying patterns basically remain. Executions of Witches may no longer occur (at least in Europe or North America), but the essence of the pattern is alive and well. Norman Cohn had hypothesized that part of the psychological roots of the more lurid aspects of the common beliefs about Witches and their orgiastic sabbats lay in Christianity ‘exalting spiritual values at the expense of the animal side of human nature’, resulting in ‘unconscious resentment against Christianity as too strict a religion and Christ as too stern a taskmaster.’35 That is likely so, but Cohn seems to apply this interpretation only to the common people (read: mostly women), and fails to include the religious clergy itself (read: mostly men).

The celibate priest or monk (of whatever tradition) is by definition an unnatural person, because he (and it is usually a he) is commonly in a kind of war with himself, living in a perpetual state of repression. This repression will naturally seek outlets, and the Christian image of the Devil—a dark, hoofed, horned, freakish creature who requires women to kiss his ass multiple times (as well as his genitals)—can hardly be more than the outer face of repressed sexual energy. He is, essentially, the celibate priest inverted, as much as he is the inversion of the plastic Jesus of perfect purity who entered the world via a virgin.

From this perspective, the priest and the Devil can be seen as two sides of the same coin. Cohn’s view that the Devil and his sabbat—including orgies and the strange legend of Witches ‘eating babies’, itself an echo of old Greek infanticide myths involving certain annoyed Gods (like Chronos/Saturn) attempting to eat their children—is a fantasy that is the product of the Christian-hating, God-hating, and Jesus-hating frustrated public, probably carries some truth. But almost certainly the ‘horny’ Devil and his harem of nympho-maniacal ‘Witches’ is equally so a product of male celibate ecclesiastical unconscious fantasy. Further, it is also reasonable to conjecture that the inclusion of the anus as part of the ‘diabolic’ ritual is a suggestion of repressed homosexual tendencies. That celibate priests and monks often become homosexually (or at the least, bisexually) oriented, is common knowledge.

The lesson we can glean from the Witch-craze tragedy is on many levels, but certainly the issue of integrating our loftier, spiritual impulse with our earthy, animal nature, is at the forefront. The Witch-craze was very much a sexual phenomenon—regardless of the many other realms of human concern it touched on (religious, social, economic). At a superficial look it may seem as if persecuting ‘Witches’ was a need of the Church to exert control over potentially dangerous usurpers, but looked at a bit closer the whole thing can be seen as both the Church’s, and common person’s, need to exert control over disowned ‘shadow’ elements from within. We generally seek to punish that which reminds us most uncomfortably about the part of ourselves that we have not come to terms with, and we often ‘see’ these disowned qualities in the world around us. That, ultimately, transcends the issue of gender. We all carry within us the seeds of an Inquisitor or torturer—the capacity for intolerance, for unreasoned judgment, for sadistic dominance. And we equally carry within the seeds of both Devil and the Church’s ‘Witch’—the former as a darkened, shadowy, furtive expression of guilt, and the latter as a primal expression of lust, power, and rebellion against authority. We also carry within us the ancient need to explain death, to assign cause to the unknown, to go on ‘Witch-hunts’ in order to relieve ourselves of the burden of not knowing the cause of unforeseen negative circumstances—in short, to be victims, and to be righteous in that stance.

It is perhaps fitting that the modern Wiccan (Witch) practices a religion that is innocuous and concerned with healing and spiritual awakening; and above all with being attuned to that which is natural. The Witch-craze and its shadowy archetypes was a manifestation of an unnatural internal split in the mind—the artificial disconnect between ‘angel’ and ‘devil’, between selflessness and self-centeredness. To be truly natural is to bring the two together, so as to move beyond both—beyond the limitations of being bloodless, self-sacrificing and self-loathing, and beyond the limitations of being crude, narcissistic, and driven by selfish impulse.

Notes

1. www.malleusmaleficarum.org.

2. Modern Witchcraft (Wicca) and related neo-Pagan faiths are very popular here in the early 21st

century, and as such there are innumerable books available explaining

the tradition from the point of view of a modern Witch, neo-Pagan, or

sympathetic writer. Possibly the best of these was written by Margot

Adler (granddaughter of the famed psychologist Alfred Adler). The book

is Drawing Down the Moon (Boston: Beacon Press), originally published in 1979, appearing in revised editions in 1986, 1996, and 2006. There are many scholarly treatments of the subject, but by far the best and most comprehensive is Ronald Hutton's The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft (Oxford University Press, 1999).

3. Oxford Concise Dictionary of English Etymology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), p. 543.

4. See John Michael Greer, The New Encyclopedia of the Occult (St. Paul: Llewellyn Publications, 2005), pp. 516-517.

5. See http://www.proteuscoven.org/proteus/Suffer.htm, accessed June 30, 2010

6. www.reuters.com/article/idUSL21301127, accessed June 30, 2010.

7. www.cnn.com/2009/WORLD/asiapcf/01/08/png.witchcraft/index.html, accessed July 6, 2010.

8. Rossell Hope Robbins, The Encyclopedia of Witchcraft and Demonology (New York: Crown Publishers, 1959) p. 337.

9. Ibid., p. 337.

10. www.malleusmaleficarum.org

11. Robbins, The Encyclopedia of Witchcraft and Demonology, p. 4.

12. These numbers are from an exhaustive work by Ronald Hutton of Bristol University, available online at www.summerlands.com/crossroads/remembrance/current.htm (accessed July 1, 2010).

13. James Sharpe, Instruments of Darkness: Witchcraft in England 1550-1750 (London: Penguin Books, 1997), p. 111.

14. Gerald Gardner, Witchcraft Today (New York: Magickal Childe Publishing, 1991), p. 35. (Originally published in England by Rider & Co., 1954).

15. Gerard Messadie, A History of the Devil (New York: Kodansha America Inc., 1997), p. 255.

16. Norman Cohn, Europe’s Inner Demons (Frogmore: Paladin, 1976), pp. 101-102.

17. Jack Kelly, Gunpowder Alchemy, Bombards, & Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World (New York: Basic Books, 2004), p.32.

18. James Frazer, The Golden Bough (London: Papermac, 1991 edition), for example, pp. 194-195.

19. Mircea Eliade, Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy (Princeton University Press, 1974 edition), p. 508.

20. Cohn, Europe’s Inner Demons, pp. 239-252.

21. Claude Levi-Strauss, Magic, Witchcraft, and Curing (edited by John Middleton; Garden City: The Natural History Press, 1967), p. 23.

22. For an in depth article on the Salem Witch trials, see Robbins, The Encyclopedia of Witchcraft and Demonology, pp. 429-448. Credible sources can also be found online.

23. See Cohn, Europe’s Inner Demons, pp. 225-255.

24. Thomas Robisheaux, The Last Witch of Langenburg (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2009).

25. The jury remains out on some of these, especially Gurdjieff’s Sarmoung legend, Castaneda’s native shaman don Juan, and Markides’ Greek mystics, which some commentators grant may have had, or still have, some semblance of physical reality. Renard, the author of popular New Age works like The Disappearance of the Universe and Your Immortal Reality, is the most recent example. Much as with readers of Castaneda’s works in the 1970s and 80s, fans of Renard tend to care less about the veracity of his ‘ascended master’ teachers, as they value the teachings themselves, and the entertaining way in which they are conveyed.

26. Greer, The New Encyclopedia of the Occult (St. Paul: Llewellyn Publications, 2005), pp. 108-109, and 188.

27. There appears to be some scholarly disagreement over the nature of this ‘empowerment’ bequeathed by Crowley to Gardner. Crowley’s biographer Richard Kaczynski claims that the empowerment was authentic, but John Michael Greer questions this, saying the ‘OTO Charter’ appears to have been written in Gardner’s hand, and contains a grammatical error—‘Do what thou wilt shall be the Law’ rather than the correct ‘Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law’—an error that Greer believes Crowley would never have made. (See Greer, Ibid., p. 188). That noted, it is possible, even likely, that Crowley was dictating to Gardner and the latter simply wrote Crowley’s words down inaccurately. Crowley frequently dictated to others—the entirety of his Diary of a Drug Fiend and large parts of his Confessions were dictated to his Scarlet Women at the time.

28. See Raymond Buckland’s Introduction to Gerald Gardner’s Witchcraft Today (New York: Magickal Childe Publishing, 1991), p. v.

29. Richard Kaczynski, Perdurabo: The Life of Aleister Crowley (Tempe, New Falcon Publications, 2002), p. 448. As a long standing member of Crowley’s OTO organization and a Crowley biographer, we can grant Kaczynski a certain inevitable bias, but his research is hard to refute when the facts he mentions are chased down.

30. Cohn, Europe’s Inner Demons, p. 109. For Cohn’s entire (and convincing) deconstruction of Murray’s thesis, see pp. 108-120.

31. For Crowley aficionados, Frazer’s ideas around the ‘sacrificed’ or ‘dying king’ appear to have been a major influence on Crowley’s ideas around the ‘Osirian Age’, previous to what he believed to be the current ‘Aeon of Horus’, begun in 1904 as heralded by his The Book of the Law. Crowley was known to have made a serious study of Frazer.

32. Cohn, p. 117.

33. Adler, Drawing Down the Moon (1986 edition) p. 52.

34. Isaac Bashevis Singer, back cover blurb to Richard Cavendish’s The Black Arts (New York: A Perigee Book, 1983).

35. Cohn, p. 262.

Copyright 2010 by P.T. Mistlberger, all rights reserved.

______________________________________________________

Romeo and Juliet

Star-Crossed Lovers and Families at War

by P.T. Mistlberger

Two households, both alike in dignity,

In fair Verona, where we lay our scene,

From ancient grudge break to new mutiny,

Where civil blood makes civil hands unclean.

From forth the fatal loins of these two foes

A pair of star-cross'd lovers take their life…

—Romeo and Juliet (Prologue)

Background

The notion of the ‘star-crossed’ lovers is ancient and archetypal. It refers to a love relationship that is doomed from the beginning, predestined to tragedy, having an ending that is as fixed as the motions of the stars above. On one level the term ‘star-crossed’ alludes to astrology, an ancient art first practiced in Babylon over three thousand years ago (and possibly earlier in Sumeria), based largely on the premise that the positions of the stars overhead (which includes, in this sense, the planets) has a direct bearing on earthly events, and on an individual’s fate. As in the Hermetic maxim, as above, so below, the heavens were thought by the ancients to directly reflect and influence the affairs of men and women.